14.1 The Genetic Code

Codons specify amino acids

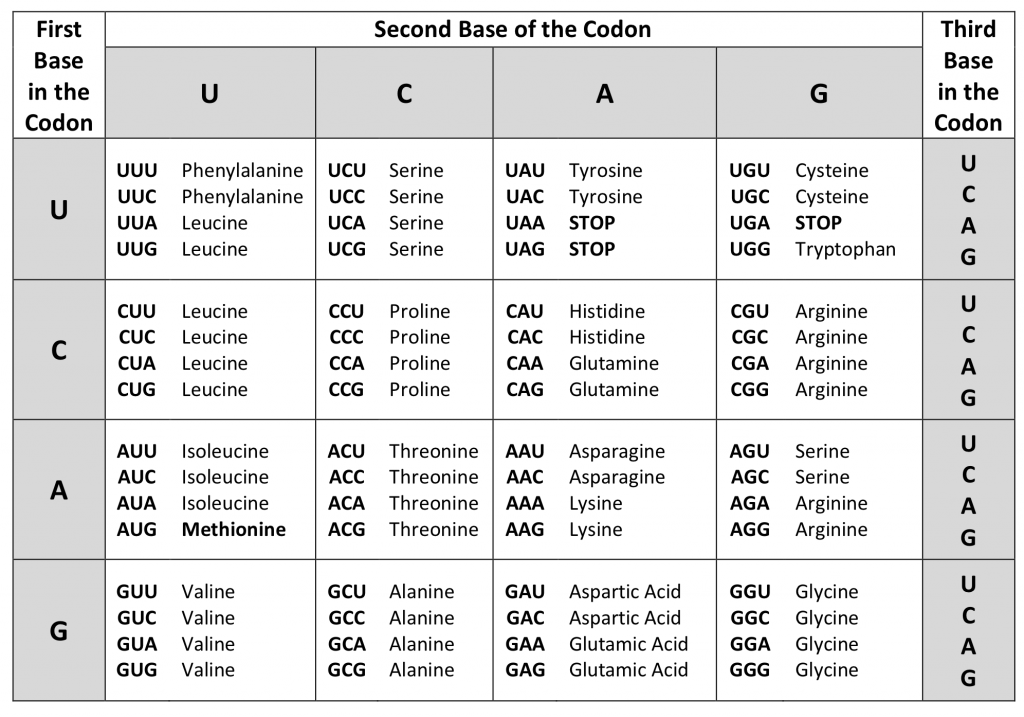

Each amino acid is defined by a three-nucleotide sequence called a triplet codon, or simply a codon. Given the different numbers of “letters” in the mRNA and protein “alphabets,” scientists theorized that single amino acids must be represented by combinations of nucleotides. Nucleotide doublets would not be sufficient to specify every amino acid because there are only 16 possible two-nucleotide combinations (42). In contrast, there are 64 possible nucleotide triplets (43), and there are 20 different amino acids encoded. Scientists theorized that amino acids were encoded by nucleotide triplets and that the genetic code was “degenerate.” In other words, a given amino acid could be encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet. This was later confirmed experimentally: Francis Crick and Sydney Brenner used the chemical mutagen proflavin to insert one, two, or three nucleotides into the gene of a virus. When one or two nucleotides were inserted early in the coding sequence, the normal proteins were not produced. When three nucleotides were inserted, the protein was synthesized and functional. This demonstrated that the amino acids must be specified by groups of three nucleotides. These nucleotide triplets are called codons. The insertion of one or two nucleotides completely changed the triplet reading frame, thereby altering the message for every subsequent amino acid. Though insertion of three nucleotides caused an extra amino acid to be inserted during translation, the integrity of the rest of the protein was maintained.

The Genetic Code Is Degenerate

In addition to codons that instruct the addition of a specific amino acid to a polypeptide chain, three of the 64 codons terminate protein synthesis and release the polypeptide from the translation machinery without the attachment of an amino acid. These triplets are called nonsense codons, or stop codons. Another codon, AUG, also has a special function. In addition to specifying the amino acid methionine, it also serves as the start codon to initiate translation. The reading frame for translation is set by the AUG start codon near the 5′ end of the mRNA. Following the start codon, the mRNA is read in groups of three until a stop codon is encountered.

The arrangement of the coding table reveals the structure of the code. There are sixteen “blocks” of codons, each specified by the first and second nucleotides of the codons within the block, e.g., the “AC*” block that corresponds to the amino acid threonine (Thr). Some blocks are divided into a pyrimidine half, in which the codon ends with U or C, and a purine half, in which the codon ends with A or G. Some amino acids get a whole block of four codons, like alanine (Ala), threonine (Thr) and proline (Pro). Some get the pyrimidine half of their block, like histidine (His) and asparagine (Asn). Others get the purine half of their block, like glutamate (Glu) and lysine (Lys). Note that some amino acids get a block and a half-block for a total of six codons.

The specification of a single amino acid by multiple similar codons is called “degeneracy.” Degeneracy is believed to be a cellular mechanism to reduce the negative impact of random mutations. Codons that specify the same amino acid typically only differ by one nucleotide. In addition, amino acids with chemically similar side chains tend to be encoded by similar codons. For example, aspartate (Asp) and glutamate (Glu), which occupy the GA* block, are both negatively charged. This nuance of the genetic code causes a single-nucleotide substitution mutation to sometimes specify the same amino acid (and therefore have no effect on protein function) or a similar amino acid (increasing the chances for the protein to retain complete or partial function).

The genetic code is nearly universal.

With a few minor exceptions, virtually all species use the same genetic code for protein synthesis. Conservation of codons means that a purified mRNA encoding the globin protein in horses could be transferred to a tulip cell, and the tulip would synthesize horse globin. That there is only one genetic code is powerful evidence that all of life on Earth evolved from a common ancestor, especially considering that there are about 1084 possible combinations of 20 amino acids and 64 triplet codons.

three consecutive nucleotides in mRNA that specify the insertion of an amino acid or the termination and release of a polypeptide chain during translation

describes that a given amino acid can be encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet codon

one of the three mRNA codons that specifies termination of translation

type of nitrogenous base in DNA and RNA with one carbon-nitrogen ring; cytosine, thymine, and uracil are pyrimidines

type of nitrogenous base in DNA and RNA with two carbon-nitrogen rings; adenine and guanine are purines

a change in DNA sequence. Mutations can be as simple as a single nucleotide substitution or as complex as a chromosome rearrangement.