1.1 Major Groups of Living Organisms

Groups of Life

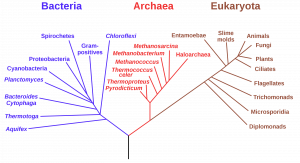

In the recent past, scientists grouped living things into five kingdoms—animals, plants, fungi, protists, and prokaryotes—based on physical traits, such as the absence or presence of a nucleus, the absence or presence of cell walls, multicellularity, etc. However, in the late 20th century scientists realized that comparing DNA sequences was a more accurate method for grouping organisms according to their evolutionary history.

In 1977, Carl Woese and his colleagues proposed that all life on Earth evolved along three lineages, called domains. The domain Bacteria comprises all organisms in the kingdom Bacteria, the domain Archaea comprises the rest of the prokaryotes, and the domain Eukarya comprises all eukaryotes—including organisms in the kingdoms Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, and the protists.

Properties of all cells

Prokaryotes

Eukaryotes

Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells have a nucleus, as well as other membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotes used to be classified into four kingdoms (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, and Protista), but molecular data has shed light on the relationships between eukaryotic groups, and demonstrated that this classification scheme is incorrect. Eukaryotes are currently classified into five supergroups (Opisthokonta, Amoebozoa, Excavata, Archaeplastida, and SAR), but this may change with new information.

Some eukaryotes are unicellular, and others are multicellular. Multicellularity has evolved independently many times in eukaryotes, including in the groups that gave rise to animals, fungi, and plants. All animals and plants are multicellular, and some fungi are. We use the word “protist” as an informal name to refer to eukaryotes that are not animals, plants, or fungi. Protists are extremely diverse, and can be either unicellular or multicellular.

1. Red algae by Franz Eugen Köhler is in the public domain. Giant Kelp by Claire Fackler is in the public domain. Frontonia by Wiedehopf20 is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 license. Dinobryon by Frank Fox is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany license. Radiolaria by Patrick De Wever is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 license. Giardia by Dr. Stan Erlandsen is in the public domain. Acanthamoeba by Jacob Lorenzo-Morales et. al is used under a Creative Commons Attribution license. Fuligo septica by Urmas Tartes is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

organisms which are comprised of cells that lack a nucleus

the highest taxonomic rank; life is classified into three domains

organisms that are comprised of cells that have a nucleus

informal name for eukaryotes that are not animals, plants, or fungi

structure that separates the interior of the cell from its environment

cellular structure that synthesizes proteins