11.4 Response to the Signal and Termination

Response to the Signal

The results of signaling pathways are extremely varied and depend on the type of cell involved as well as the external and internal conditions. A small sampling of responses is described below.

Gene Expression

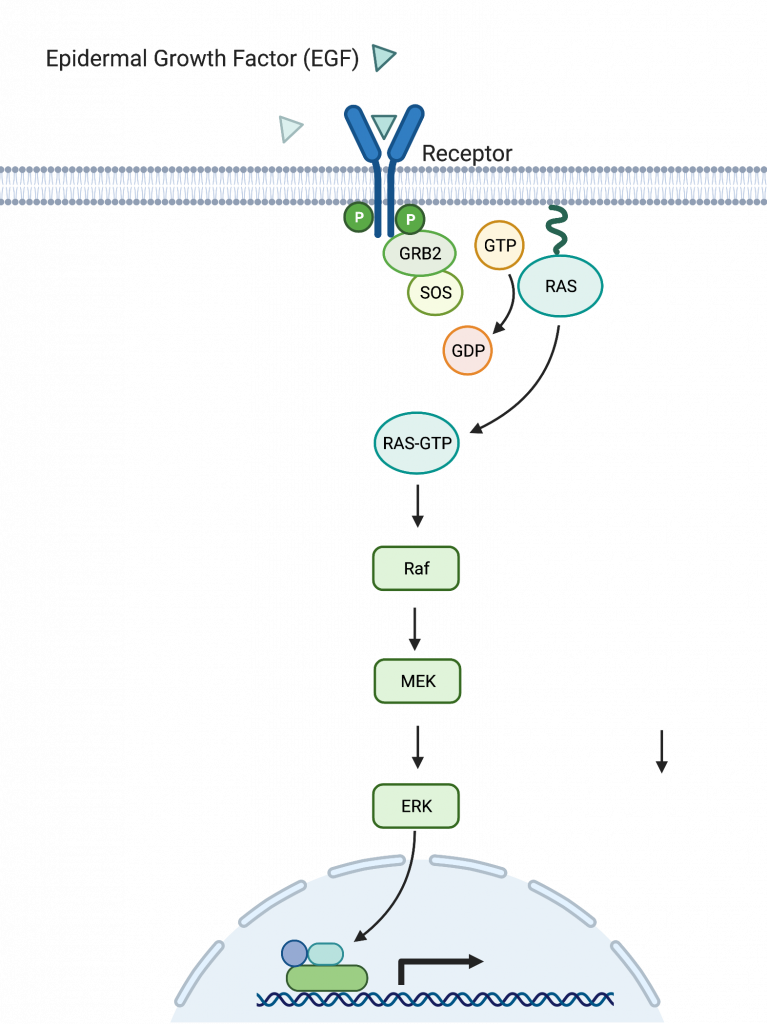

Some signal transduction pathways regulate the transcription of RNA. Others regulate the translation of proteins from mRNA. An example of a protein that regulates translation in the nucleus is the MAP kinase ERK. The MAPK/ERK pathway is a chain of proteins in the cell that communicates a signal from a receptor on the surface of the cell to the nuclear DNA. ERK is activated in a phosphorylation cascade when epidermal growth factor (EGF) binds the EGF receptor. Upon phosphorylation, ERK enters the nucleus and activates a protein kinase that, in turn, regulates protein transcription.

Increase in Cellular Metabolism

The result of another signaling pathway affects muscle cells. The activation of β-adrenergic receptors in muscle cells by adrenaline leads to an increase in cyclic AMP (cAMP) inside the cell. Also known as epinephrine, adrenaline is a hormone (produced by the adrenal gland located on top of the kidney) that readies the body for short-term emergencies. Cyclic AMP activates PKA (protein kinase A), which in turn phosphorylates two enzymes. The first enzyme promotes the degradation of glycogen by activating intermediate glycogen phosphorylase kinase (GPK) that in turn activates glycogen phosphorylase (GP) that catabolizes glycogen into its constituent glucose monomers. (Recall that your body converts excess glucose to glycogen for short-term storage. When energy is needed, glycogen is quickly reconverted to glucose.) Phosphorylation of the second enzyme, glycogen synthase (GS), inhibits its ability to form glycogen from glucose. In this manner, a muscle cell obtains a ready pool of glucose by activating its formation via glycogen degradation and by inhibiting the use of glucose to form glycogen, thus preventing a futile cycle of glycogen degradation and synthesis. The glucose is then available for use by the muscle cell in response to a sudden surge of adrenaline—the “fight or flight” reflex.

Cell Growth

Cell signaling pathways also play a major role in cell division. Cells do not normally divide unless they are stimulated by signals from other cells. The ligands that promote cell growth are called growth factors. Most growth factors bind to cell-surface receptors that are linked to tyrosine kinases. These cell-surface receptors are called receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Activation of RTKs initiates a signaling pathway that includes a G-protein called RAS, which activates the MAP kinase pathway described earlier. The enzyme MAP kinase then stimulates the expression of proteins that interact with other cellular components to initiate cell division.

Cell Death

When a cell is damaged, superfluous, or potentially dangerous to an organism, a cell can initiate a mechanism to trigger programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Apoptosis allows a cell to die in a controlled manner that prevents the release of potentially damaging molecules from inside the cell. There are many internal checkpoints that monitor a cell’s health; if abnormalities are observed, a cell can spontaneously initiate the process of apoptosis. However, in some cases, such as a viral infection or uncontrolled cell division due to cancer, the cell’s normal checks and balances fail.

External signaling can also initiate apoptosis. For example, most normal animal cells have receptors that interact with the extracellular matrix, a network of glycoproteins that provides structural support for cells in an organism. The binding of cellular receptors to the extracellular matrix initiates a signaling cascade within the cell. However, if the cell moves away from the extracellular matrix, the signaling ceases, and the cell undergoes apoptosis. This system keeps cells from traveling through the body and proliferating out of control, as happens with tumor cells that metastasize.

Termination of the Signal

Termination of a signal at the appropriate time can be just as important as the initiation of a signal. One method of stopping a specific signal is to degrade the ligand or remove it so that it can no longer access its receptor.

Inside the cell, many different enzymes reverse the cellular modifications that result from signaling cascades. For example, phosphatases remove the phosphate group attached to proteins by kinases in a process called dephosphorylation. Cyclic AMP (cAMP) is degraded into AMP, and the release of calcium stores is reversed by the Ca2+ pumps that are located in the external and internal membranes of the cell.

ligand that binds to cell-surface receptors and stimulates cell growth

programmed cell death

enzyme that removes the phosphate group from a molecule that has been previously phosphorylated

enzyme that phosphorylates a molecule