18.2 Life Cycles of Sexually Reproducing Organisms

Fertilization and meiosis alternate in sexual life cycles. What happens between these two events depends on the organism’s “reproductive strategy.” The process of meiosis reduces the chromosome number in a cell by half. Fertilization, the joining of two haploid gametes, restores the diploid condition. Some organisms have a multicellular diploid stage that is most obvious and the only haploid cells produced are the reproductive cells. Animals, including humans, have this type of life cycle. Other organisms, such as fungi, have a multicellular haploid stage that is most obvious. Plants and some algae have alternation of generations, in which they have both multicellular diploid and haploid life stages that are apparent to different degrees depending on the group.

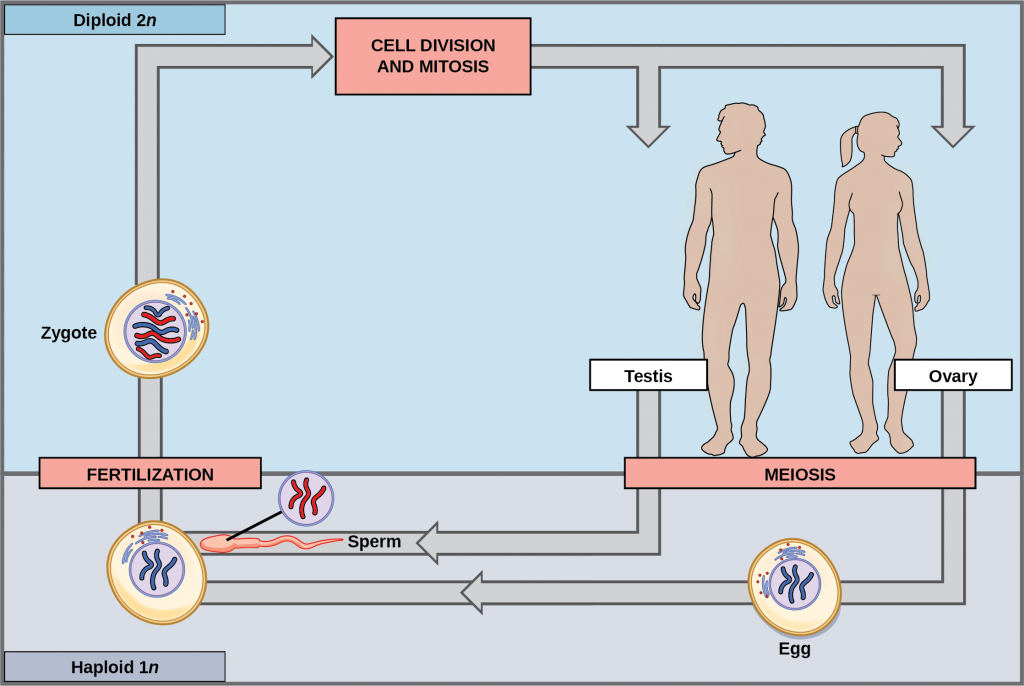

Nearly all animals employ a diploid-dominant life-cycle strategy in which the only haploid cells produced by the organism are the gametes. Early in the development of the embryo, specialized diploid cells, called germ cells, are produced within the gonads (such as the testes and ovaries). Germ cells are capable of both mitosis to perpetuate the germ cell line and meiosis to produce haploid gametes. Once the haploid gametes are formed, they lose the ability to divide again. There is no multicellular haploid life stage. Fertilization occurs with the fusion of two gametes, usually from different individuals, restoring the diploid state.

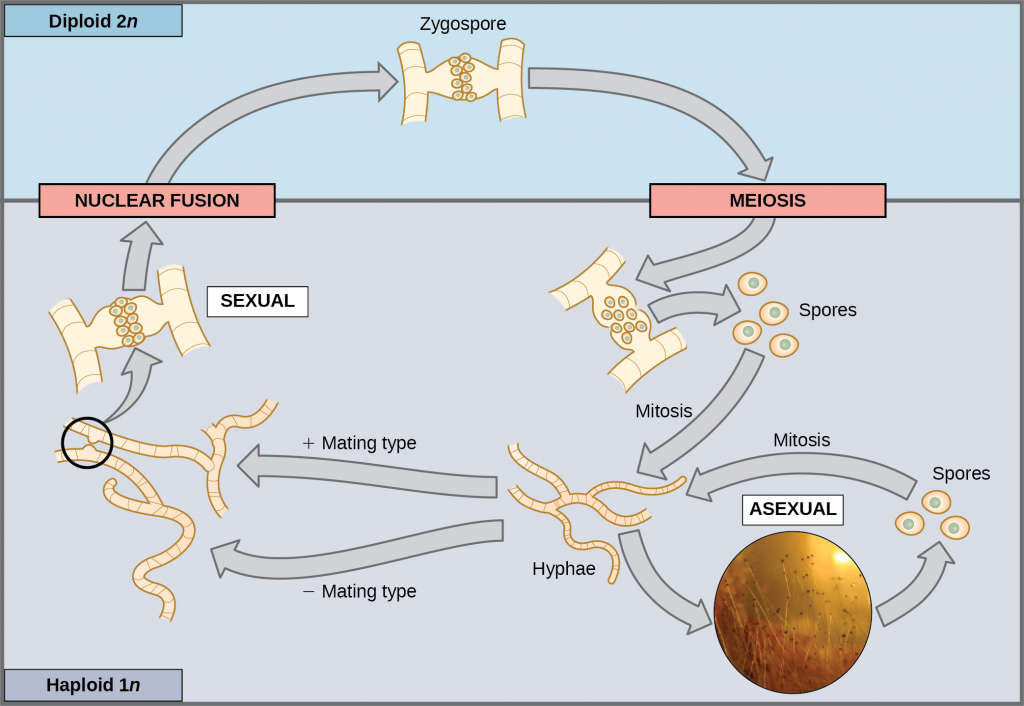

Most fungi and algae employ a life-cycle type in which the “body” of the organism—the ecologically important part of the life cycle—is haploid. The haploid cells that make up the tissues of the dominant multicellular stage are formed by mitosis. During sexual reproduction, specialized haploid cells from two individuals—designated the (+) and (−) mating types—join to form a diploid zygote. The zygote immediately undergoes meiosis to form four haploid cells called spores. Although these spores are haploid like the “parents,” they contain a new genetic combination from two parents. The spores can remain dormant for various time periods. Eventually, when conditions are favorable, the spores form multicellular haploid structures through many rounds of mitosis.

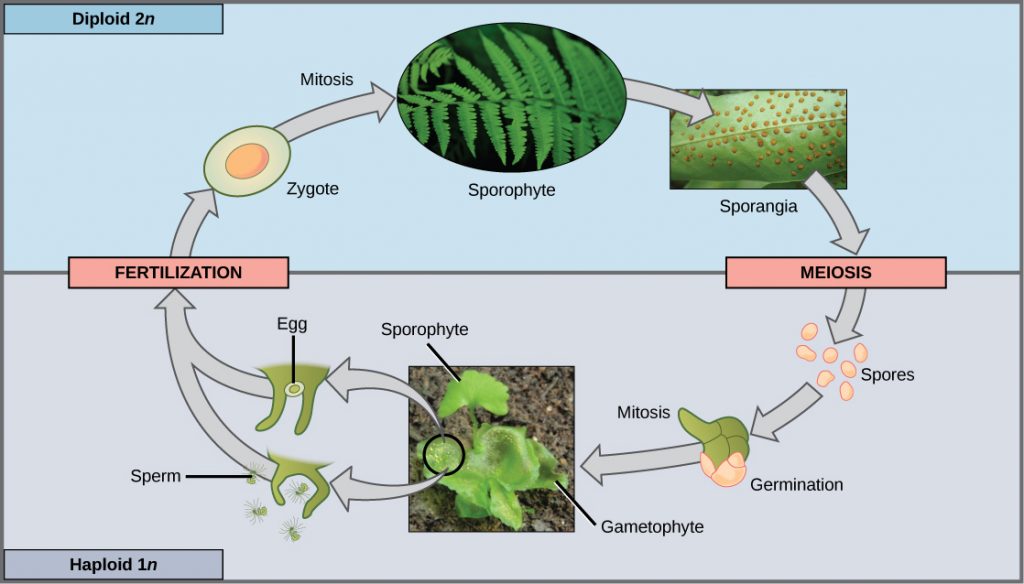

The third life-cycle type, employed by some algae and all plants, is a blend of the haploid-dominant and diploid-dominant extremes. Species with alternation of generations have both haploid and diploid multicellular organisms as part of their life cycle. The haploid multicellular plants are called gametophytes, because they produce gametes from specialized cells. Meiosis is not directly involved in the production of gametes in this case, because the organism that produces the gametes is already haploid. Fertilization between the gametes forms a diploid zygote. The zygote will undergo many rounds of mitosis and give rise to a diploid multicellular plant called a sporophyte. Specialized cells of the sporophyte will undergo meiosis and produce haploid spores. The spores will subsequently develop into the gametophytes.

Although all plants utilize some version of the alternation of generations, the relative size of the sporophyte and the gametophyte and the relationship between them vary greatly. In plants such as moss, the gametophyte organism is the free-living plant and the sporophyte is physically dependent on the gametophyte. In other plants, such as ferns, both the gametophyte and sporophyte plants are free-living; however, the sporophyte is much larger. In seed plants, such as magnolia trees and daisies, the gametophyte is composed of only a few cells and, in the case of the female gametophyte, is completely retained within the sporophyte.

Sexual reproduction takes many forms in multicellular organisms. The fact that nearly every multicellular organism on Earth employs sexual reproduction is strong evidence for the benefits of producing offspring with unique gene combinations, though there are other possible benefits as well.