Planet Earth

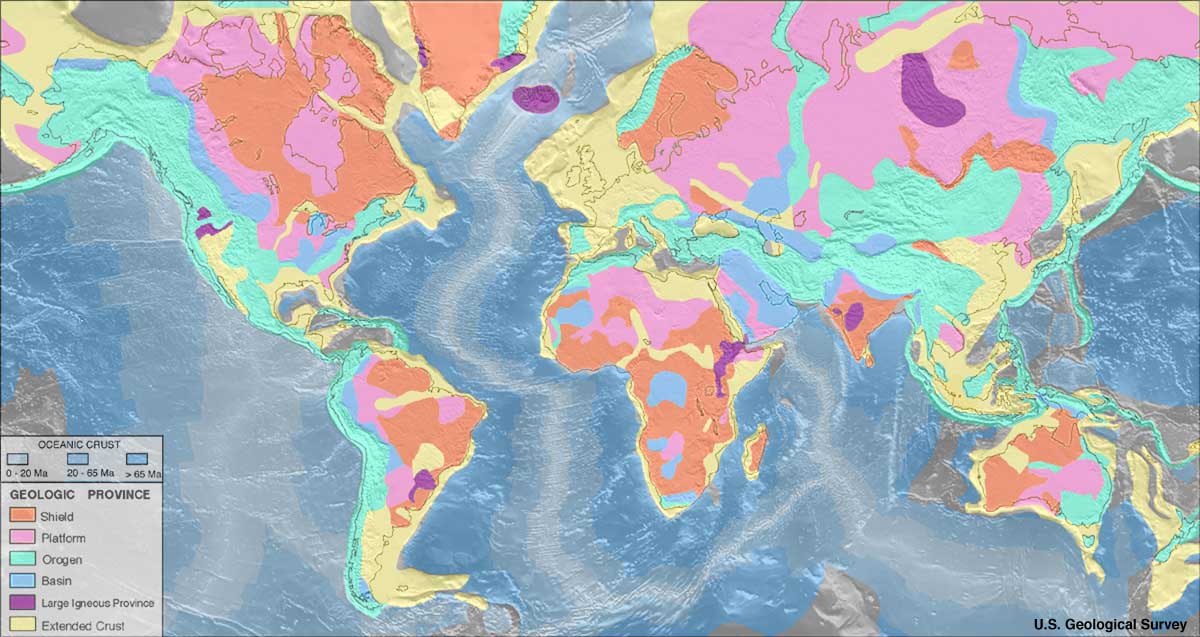

3.7 Tectonic Plate Boundaries

Places where oceanic and continental lithospheric tectonic plates meet and move relative to each other are called active margins (e.g., the western coasts of North and South America). A location where the continental lithosphere transitions into the oceanic lithosphere without movement is a passive margin (e.g., the eastern coasts of North and South America). Therefore, tectonic plates may be made of both oceanic and continental lithosphere. In plate tectonics, the movement of the lithospheric plates is the primary force that causes the majority of features and activity on the Earth’s surface that can be attributed to plate tectonics. This movement occurs (at least partially) via the drag of motion within the asthenosphere and because of density. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

As they move, the tectonic plates interact at the boundaries between the tectonic plates. These interactions are the primary drivers of the planet’s mountain building, earthquakes, and volcanism. A simplified plate tectonic model can place plate interaction in three categories. In places where plates move toward each other, the boundary is convergent. In areas where plates move apart, the boundary is known as divergent. Finally, the boundary is a transform boundary in places where the plates slide past each other. The next three subchapters will explain the details of the movement at each type of boundary.

Convergent Boundaries

Convergent boundaries, sometimes called destructive boundaries, are places where two or more tectonic plates have a net movement toward each other. More than any other, convergent boundaries are known for orogenesis, the process of building mountains and mountain chains. The key to convergent boundaries is understanding the density of each plate involved in the movement. For example, the continental lithosphere is always lower in density and is buoyant compared to the asthenosphere. On the other hand, the oceanic lithosphere is denser than the continental lithosphere and, when old and cold, may even be denser than the asthenosphere. When plates of different densities converge, the denser plate sinks beneath the less dense plate, a process called subduction. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

Subduction is when the oceanic lithosphere descends into the mantle due to density. The average subduction rate of oceanic crust worldwide is 25 miles per million years, about a half-inch per year. Continental lithosphere can partially subduct if attached to the sinking oceanic lithosphere, but its buoyancy does not allow it to subduct fully. As the tectonic plate descends, it pulls the ocean floor down in a trench feature. On average, the ocean floor is around 3-4 km deep. The ocean can be more than twice as deep in trenches, with the Mariana Trench approaching 11 km.

Within the trench is a feature called the accretionary wedge, sometimes known as melange or accretionary prism, which is a mix of ocean floor sediments that are scraped and compressed at the boundary between the subducting the overriding plate. Sometimes, pieces of continental material, like microcontinents, riding with the subducting plate will become sutured to the accretionary wedge, forming a terrane. Substantial portions of California are comprised of accreted terranes.

When the subducting plate, known as a slab, submerges into the depths of the mantle, the heat and pressure are so immense that lighter materials, known as volatiles, like water and carbon dioxide, are pushed out of the subducting plate into an area called the mantle wedge. The volatiles are released primarily via hydrated minerals that revert to non-hydrated forms in these conditions. When mixed with asthenospheric material above the tectonic plate, these volatiles lower the material’s melting point. At the temperature of that depth, the material melts to form magma. This process of magma generation is called flux melting. Because of its lower density, Magma migrates toward the surface, creating volcanism. This forms a curved chain of volcanoes because many boundaries are curved on a spherical Earth. A feature is called an arc. The overriding plate, which contains the arc, can be oceanic or continental, where some features differ, but the general architecture remains the same.

How subduction initiates is still a matter of some debate. This would start at passive margins where oceanic and continental crust meet. Currently, the oceanic lithosphere is denser than the underlying asthenosphere on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, which is not presently subducting. Why has it not turned into an active margin? Firstly, there is strength in the connection between the dense oceanic lithosphere and the less dense continental lithosphere it is connected to, which needs to be overcome. Gravity could cause the denser oceanic plate to force itself down, or the plate can start to flow flexibly at a low angle. There is evidence that new subduction is starting off the coast of Portugal. Massive earthquakes, like the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake, may even have something to do with creating a subduction zone, though it is not definitive. Transform boundaries that have brought different densities together is also thought to start subduction. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

Besides volcanism, subduction zones are known for the most massive earthquakes globally. In places, the entire subducting slab can become stuck. When the energy has built up too high, the whole subduction zone can slide simultaneously along a zone extending hundreds of kilometers along the trench, creating enormous earthquakes and tsunamis. The earthquakes can be significant, but they can be profound, outlining the subducting slab as it descends. Subduction zones are the only places on Earth with fault surfaces large enough to create 9.0 magnitude earthquakes. Also, because the faulting occurs beneath seawater, subduction can create giant tsunamis, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake in Japan.

Subduction, a convergent motion, can have varying degrees of convergence. In places with a high convergence rate, primarily due to young, buoyant oceanic crust sub-ducting, the subduction zone can create faulting behind the arc area, known as back-arc faulting. This faulting can be tensional, or this area is subject to compressional forces. A modern example of this occurs in the two ‘spines’ of the Andes Mountains. In the west, the mountains are formed from the volcanic arc; in the east, thrust faults have pushed up another non-volcanic mountain range still part of the Andes. This type of thrusting can typically occur in two styles: thin-skinned, which only faults surficial rocks, and thick-skinned, which thrusts deeper crustal rocks. Thin-skinned deformation notably happened in the western US during the Cretaceous Sevier Orogeny. Near the end of the Sevier Orogeny, thick-skinned deformation also occurred in the Laramide Orogeny.

The Laramide orogeny is also known for another subduction feature: flat-slab subduction. When the slab subducts at such a low angle, there is an interaction between the slab and the overlying continental plate. Magmatic activity can give rise to mineral deposits, and deformation can occur well into the interior of the overriding plate. All subduction zones have a forearc basin between the arc and the trench. This high thrust faulting and deformation area is seen mainly within the accretionary wedge. There are also places where the convergence shows the results of tensional forces. Various causes have been proposed, including slab roll-back due to density or ridge migration. This causes extension behind the volcanic or island arc, a back-arc basin. These can have so much extension that rifting and divergence can develop, though they can be more asymmetric than their mid-ocean ridge counterparts. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

Oceanic-Continental Subduction

Oceanic-continental subduction occurs when an oceanic plate dives below a continental plate. These regions can have powerful earthquakes along the subduction zones, potentially generating tsunamis. This boundary has a trench and mantle wedge, but the volcanoes are expressed in a feature known as a volcanic arc. A volcanic arc is a chain of mountain volcanoes, with famous examples including the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest and the Andes Mountains of South America.

Oceanic-Oceanic Subduction

Oceanic-oceanic subduction zones have two significant differences from boundaries that have continental lithosphere. Firstly, each plate in an ocean-ocean plate boundary is capable of subduction. Therefore, it is typical that the denser, older, and colder of the two plates is the one that subducts. Since both plates are oceanic, volcanism creates volcanic islands instead of continental volcanic mountain ranges. This chain of active volcanoes is known as an island arc. Many examples of this on Earth include the Aleutian Islands off of Alaska, the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean, and several island arcs in the western Pacific.

Continental-Continental Convergence

In places where two continental plates converge, subduction is not possible. This occurs when an ocean basin closes, and a passive margin is attempted to drive down the subducting slab. Instead of subducting beneath the continent, the two masses of continental lithosphere slam into each other in a process known as a collision. Collision zones are known for tall mountains and frequent, massive earthquakes with little to no volcanism. With subduction ceasing with the crash, there is no process to create the magma for volcanism.

Continental plates are too low-density to subduct, so the collision occurs instead of subduction. Unlike the dense subducting slabs that form from oceanic plates, any attempt to subduct continental plates is short-lived. An occasional exception is obduction, in which a part of a continental plate is caught beneath an oceanic plate, formed in collision zones or with small plates caught in subduction zones. This imbalance in density is solved by the continental material buoying upward, bringing oceanic floor and mantle material to the surface, and is the primary source of ophiolites. An ophiolite consists of rocks from the ocean floor that are moved onto the continent, exposing parts of the mantle on the surface.

Foreland basins can also develop near the mountain belt, as the lithosphere is depressed due to the mountain’s mass. While subduction mountain ranges can cause this, collisions have many examples, possibly the best modern example being the Persian Gulf, a feature only there due to the weight of the nearby Zagros Mountains. The subducting oceanic lithosphere powers collisions and eventually stops as the continental plates combine into a more substantial mass. In truth, a small portion of the continental crust can be driven down into the subduction zone, though due to its buoyancy, it returns to the surface over time. Because of the relative plastic nature of the continental lithosphere, the zone of deformation is much broader. Instead of earthquakes along a narrow boundary, collision earthquakes can be found hundreds of miles from the suture between the landmasses.

The best modern example of this process occurs concurrently in many locations across the Eurasian continent. It includes mountain building in the Pyrenees (the Iberian Peninsula converging with France), Alps (Italy converging into central Europe), Zagros (Arabia converging into Iran), and Himalayan (India converging into Asia) ranges. Eventually, as ocean basins close, continents form a massive accumulation of continents called a supercontinent, which has occurred in hundreds of million-year cycles over Earth’s history. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

Divergent Boundaries

Divergent boundaries, sometimes called constructive boundaries, are places where two or more plates have a net movement away from each other. They can occur within a continental plate or an oceanic plate. However, the typical pattern is for divergence to begin within the continental lithosphere in a process known as “rift to drift,” described below.

Continental Rifting

Because of the thickness of continental plates, heat flow from the interior is suppressed. As a result, supercontinents’ shielding is even more robust, eventually causing an upwelling of hot mantle material. This material uplift weakens the overlying continental crust. As convection beneath naturally starts pulling the material away from the area, the area begins to be de-formed by tensional stress, forming a valley feature known as a rift valley. Normal faults bound these features, including tall shoulders called horsts and deep basins called grabens. When rifts form, they can eventually create linear lakes, seas, and even oceans to form as divergent forces continue.

While initially seeming random, this breakup via rifting has two influences that dictate the shape and location of rifting. First, the stable interiors of some continents, called craton, are too strong to be broken apart by rifting. Where cratons are not a factor, rifting typically occurs with a truncated icosahedron, or “soccer ball” pattern. This is the geometric pattern of fractures requiring the least energy when expanding a sphere equally in all directions. Considering the radius of the Earth, this includes 110 km segments of deformation and volcanism, which have 120-degree turns, forming something known as failed rift arms. Even if the motion stops, a minor basin can develop in this weak spot called an aulacogen, forming long-lived basins well after tectonic processes stop. These are places where extension started but did not continue. One famous example is the Mississippi Valley Embayment, which forms a depression through which the upper end of the Mississippi River flows. In places where the rift arms do not fail, for example, the Afar Triangle, three divergent boundaries can develop near each other, forming a triple junction. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

Rifts come in two types: narrow and broad. Narrow rifts contain concentrated stress or divergent action. The best example is the East African Rift Zone, where the Horn of Africa near Somalia is breaking away from mainland Africa. Lake Baikal in Russia is also an active rift. Broad rifts distribute the deformation over many fault-bounded locations, like in the western United States in a region known as the Basin and Range. The Wasatch Fault, which created the Wasatch Range in Utah, marks the eastern edge of the Basin and Range.

Of course, earthquakes occur at rifts, though not at the severity and frequency of some other boundaries. Volcanism is also frequent in the extended, faulted, and thin lithosphere found at rift zones due to decompression melting and faults acting as conduits for the lava reaching the surface. Many relatively young volcanoes dot the Basin and Range, and bizarre volcanoes occur in East Africa, like Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania, which erupts carbonatite lavas, relatively cold liquid carbonate.

Mid-Oceanic Ridges

As rifting and volcanic activity progress, the continental lithosphere becomes more mafic and thinner, transforming the plate under the rifting area into the oceanic lithosphere. This process gave birth to a new ocean, much like the narrow Red Sea (map) that emerged with the movement of Arabia away from Africa. As the oceanic lithosphere continues to diverge, a mid-ocean ridge is formed. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

A mid-ocean ridge, also known as a spreading center, has many distinctive features. They are the only places on Earth where the new oceanic lithosphere is created via slow oozing volcanism. As the oceanic lithosphere spreads apart, the rising asthenosphere melts due to decreasing pressure and filling the void, making the new lithosphere and crust. These volcanoes produce more lava than all the other volcanoes on Earth combined. They are not usually listed on maps of volcanoes yet because most mid-ocean ridges are underwater. The volcanism and divergent characteristics seen on land are only in rare locations, such as Iceland. Technically, these places are not mid-ocean ridges because they are above the seafloor’s surface.

Alfred Wegener even hypothesized this concept of mid-ocean ridges. Because the lithosphere is extremely hot at the ridge, it has a lower density. This lower density allows it to float higher on the asthenosphere. As the lithosphere moves away from the ridge by continued spreading, the plate cools and starts to sink isostatically lower, creating the surrounding abyssal plains with lower topography. Age patterns match this idea, with younger rocks near the ridge and older rocks away from the ridge. Sediment patterns also thin toward the ridge since there is a steady dust accumulation, and biological material takes time to accumulate.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5hZsJk0G_4&feature=emb_logo

Another distinctive feature around mid-ocean ridges is magnetic striping. The Vine-Matthews-Morley Hypothesis states that as the material moves away from the ridge, it cools below the Curie Point, the temperature at which the magnetic field is imprinted on the rock as it freezes. Over time, the Earth’s magnetic field has flipped back and forth, and this change in the field causes the stripes. This pattern is an excellent record of past ocean-floor movements and can be used to reconstruct past tectonics and determine spreading rates at the ridges.

Mid-ocean ridges are also home to some of the unique ecosystems discovered. They are found around hydrothermal vents circulating ocean water through the shallow oceanic crust and sending it back to rich chemical compounds and heat. While it was known that hot fluids could be found on the ocean floor, it was only in 1977 when a team of scientists using the Diving Support Vehicle Alvin discovered a thriving community of organisms, including tubeworms bigger than people. This group of organisms is dependent on the sun and photosynthesis. Instead, it relies on chemical reactions with sulfur compounds and heat from Earth, a process known as chemosynthesis. Before this discovery, the thought in biology was that the sun was the ultimate energy source in ecosystems; now, we know this to be false. Not only that, but some have also suggested it is from this that life could have started on Earth, and it now has become a target for extraterrestrial life (e.g., Jupiter’s moon Europa).

Transform Boundaries

A transform boundary sometimes called a strike-slip or a conservative boundary, is where the motion of the plates sliding past each other is. They can move in either a dextral fashion with the side opposite moving toward the right or a sinistral fashion with the side opposite moving toward the left. Most transform boundaries can be viewed as a single fault or a series of faults. As stress builds on adjacent plates attempting to slide them past each other, a fault eventually occurs, released by an earthquake. Transform faults have a shearing motion and are prevalent where tectonic stresses are transferred. In general, transform boundaries are known for only earthquakes, with little to no mountain building and volcanism.

Most transform boundaries are associated with mid-ocean ridges. As spreading centers progress, these aseismic fracture zone transform faults accommodate different spreading amounts due to Eulerian geometry. For example, a sphere rotates faster in the middle (Equator) than at the top (Poles) and along the ridge. However, in the eyes of humanity, the more significant trans-form faults are where the motion occurs within continental plates with a shearing motion. These transform faults produce frequent moderate to large earthquakes. Famous examples include California’s San Andreas Fault, the Northern and Eastern Anatolian Faults in Turkey, the Altyn Tagh Fault in central Asia, and the Alpine Fault in New Zealand. (2 Plate Tectonics – An Introduction to Geology, n.d.)

Transpression and Transtension

Transformer faults can create secondary faulting in places where they are not straight. Transpression is defined as places with an extra component of compression with shearing. In these restraining bends, mountains can be built up along the fault. For example, the southern part of the San Andreas Fault has a large area of transpression known as the “big bend” and has built, moved, and rotated many mountain ranges in southern California.

Transtension is defined as places with an extra component of extension with shearing. In these releasing bends, depressions and sometimes volcanism are formed along the fault. For example, the Dead Sea and California’s Salton Sea are basins formed by transtensional forces.

Piercing Points

A piercing point is a feature cut by a fault and can recreate past movements along the fault. While this can be used on all faults, transform faults are most adapted for this technique. Typical and reverse faulting and divergent and convergent boundaries tend to obscure, bury, or destroy these features; transform faults generally do not. Piercing points usually consist of unique lithologic, structural, or geographic patterns that can be matched by removing the movement along the fault. Detailed studies of piercing points along the San Andreas Fault have shown over 225 km of movement in the last 20 million years along three active fault traces.

Wilson Cycle

The Wilson Cycle, named after J. Tuzo Wilson, who first described it in 1966, outlines supercontinents’ origin and subsequent breakup. This cycle has been operating for the last billion years with supercontinents Pangaea and Rodinia and possibly billions of years before. The driving force of this is two-fold. First, the more straightforward mechanism arises because continents hold the Earth’s internal heat much better than the ocean basins. When continents assemble, they hold more heat, allowing more vigorous convection and starting the rifting process. Mantle plumes are inferred to be the legacy of this increased heat and may record the history of the start of rifting. The second mechanism for the Wilson Cycle involves the destruction of plates. While rifting eventually leads to drifting continents, a few unanswered questions emerge:

- Does their continued movement result from the ridge spreading and under-lying convection, known as ridge push?

- Do the tectonic plates move because of the weight of the subducting slab sinking via its density, known as slab pull?

- Alternatively, is the ridge’s height pushing down, known as gravitational sliding?

To be sure, these are all factors in plate movement and the Wilson Cycle. However, in the current best hypothesis, there appears to be a more significant component of slab pull than ridge push. In addition, plate tectonic models are beginning to detail the next supercontinent, Pangea Proxima, that will form in 250 million years.

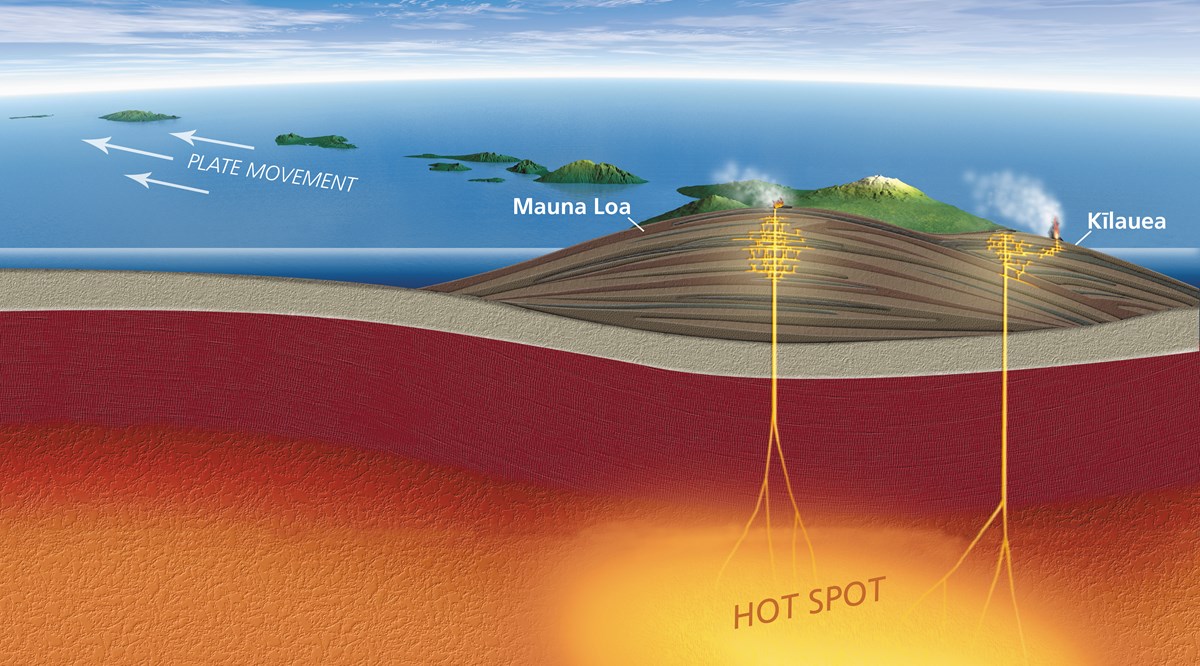

Hotspots

While the Wilson Cycle can give a general overview of plate motions in the past, another process can provide a more precise but recent plate movement. A hot spot is an area of rising magma, causing a series of volcanic centers that form volcanic islands in the ocean or craters/mountains on land. No plate tectonic process, like subduction or rifting, causes this volcanic activity; it seems disconnected from plate tectonics processes. Also first postulated by J. Tuzo Wilson in 1963, hot spots have a continual magma source with no earthquakes besides volcanism. The classic idea is that hot spots do not move, though some evidence has been suggested that the hot spots do move as well. Even though hotspots and plate tectonics seem independent, they have some relationships. They have two components: Firstly, there are currently several hot spots and others in the past that are believed to have begun at the time of rifting. Secondly, as plate tectonics moves the plates around, the assumed static nature of hot spots creates a track of volcanism that can measure past plate movement. By using the age of the eruptions from hot spots and the direction of the chain of events, one can identify a specific rate and direction of movement of a plate over the time the hot spot was active.

Hot spots are still very mysterious in their exact mechanism of magma generation. The main camps on hotspot mechanics are opposed. Some claim deep sources of heat, from as deep as the core, bring heat up to the surface in a mantle plume structure. Some have argued that not all hot spots are sourced from deep within the planet and shallower parts of the mantle. Others have mentioned how difficult it has been to imagine these deep features. The idea of how hot spots start is also controversial. Usually, divergent boundaries are tabbed at the start, especially during supercontinent breakup, though some question whether extensional or tectonic forces alone can explain the volcanism. Subducting slabs have also been named as a cause for hotspot volcanism. Even impacts of objects from space have been used to explain plumes. Finally, however, they are formed; dozens are found throughout the Earth. Famous examples include the Tahiti, Afar Triangle, Easter Island, Iceland, the Galapagos Islands, and Samoa. The United States has two of the most extensive and best-studied examples: Hawai’i and Yellowstone.

Hawaiian Hot Spot

The big island of Hawaii is the active end of the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, which stretches across the Pacific for almost 6000 km. The evidence for this hot spot goes back at least 80 million years, and presumably, the hot spot was around before then but rocks older than that in the Pacific Plate had already been subducted. The most striking feature of the chain is a significant bend about halfway through, which was 50 million years ago. The change in direction has been more often linked to plate re-configuration and other things like plume migration. While some scientists often assume that mantle plumes do not move, much like the plumes themselves, this idea is disputed.

Three-dimensional seismic imaging, called tomography, has mapped the Hawaiian mantle plume at depths, including the lower mantle. There is unmistakable evidence of the age of volcanism decreasing within the Hawaiian Islands, including island size, rock age, and even vegetation. Hawai’i is one of the most active hotspots on Earth. Kilauea, the central active vent of the hot spot eruption, has continually erupted since 1983.

Yellowstone Supervolcano

The Yellowstone Hot Spot is formed from rising magma, much like Hawai’i. The significant difference is that Hawaii sits on a thin oceanic plate, making the magma quickly surface. Yellowstone, however, is on a continental plate. The thickness of the plate causes the generally much more violent and less frequent eruptions that have carved a curved path in the western United States for over 15 million years. Some have speculated an earlier start to the hotspot, tying it to the Columbia River flood basalts and even 70 million-year-old volcanism in Canada’s Yukon.

The most significant eruption formed the current caldera and the Lava Creek Tuff. This eruption threw about 1000 cubic kilometers of magma into the atmosphere that erupted 631,000 years ago. Ash from the eruption has been found as far away as Mississippi. The next eruption, when it occurs, should be of equivalent size, causing a massive calamity to not only the western United States but also the world. These so-called “supervolcanic” eruptions have the potential for volcanic winters lasting years. With so much gas and ash filling the atmosphere, sunlight is blocked and unable to reach Earth’s surface as usual, which could drastically alter global environments and send worldwide food production into a tailspin.