4 Chapter 4: Cell Structure and Transport

Chapter Outline

- 4.1 Studying Cells

- 4.2 Prokaryotic Cells

- 4.3 Eurkaryotic Cells

- 4.4 The Endomembrane System and Proteins

- 4.5 The Cytoskeleton

- 4.6 Connections between Cells and Cellular Activities

- 4.7 Plasma Membrane Components and Structure

- 4.8 Passive Transport

- 4.9 Active Transport

- 4.10 Bulk Transport

Close your eyes and picture a brick wall. What is the basic building block of that wall? A single brick, of course. Like a brick wall, your body is composed of basic building blocks, and the building blocks of your body are cells. Your body has many kinds of cells, each specialized for a specific purpose. Just as a home is made from a variety of building materials, the human body is constructed from many cell types. For example, epithelial cells protect the surface of the body and cover the organs and body cavities within. Bone cells help to support and protect the body. Cells of the immune system fight invading bacteria. Additionally, blood and blood cells carry nutrients and oxygen throughout the body while removing carbon dioxide. Each of these cell types plays a vital role during the growth, development, and day-to-day maintenance of the body. In spite of their enormous variety, however, cells from all organisms—even ones as diverse as bacteria, onion, and human—share certain fundamental characteristics.

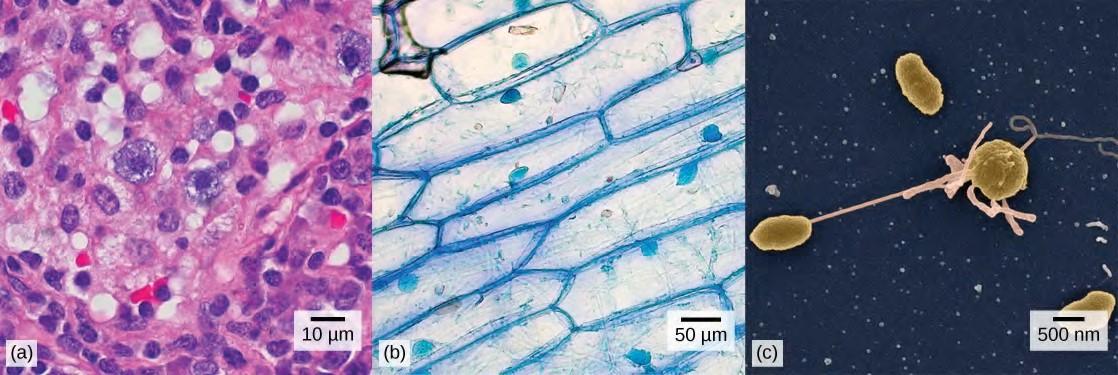

Figure 4.1 (a) Nasal sinus cells (viewed with a light microscope), (b) onion cells (viewed with a light microscope), and (c) Vibrio tasmaniensis bacterial cells (seen through a scanning electron microscope) are from very different organisms, yet all share certain characteristics of basic cell structure. (credit a: modification of work by Ed Uthman, MD; credit b: modification of work by Umberto Salvagnin; credit c: modification of work by Anthony D’Onofrio, William H. Fowle, Eric J. Stewart, and Kim Lewis of the Lewis Lab at Northeastern University; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Learning Objectives

You will be able to describe the basics of cells:

- Identify major cell components

- Differentiate the functions of cell part

- Be able to describe these characteristics of cellular transport:

- compare and contrast the different forms of membrane transport

- diffusion

- passive transport

- active transport

- vesicular transport

4.1 | Studying Cells

A cell is the smallest unit of a living thing. A living thing, whether made of one cell (like bacteria) or many cells (like a human), is called an organism. Thus, cells are the basic building blocks of all organisms. Several cells of one kind that interconnect with each other and perform a shared function form tissues, several tissues combine to form an organ (your stomach, heart, or brain), and several organs make up an organ system (such as the digestive system, circulatory system, or nervous system). Several systems that function together form an organism (like a human being). Here, we will examine the structure and function of cells. There are many types of cells, all grouped into one of two broad categories: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. For example, both animal and plant cells are classified as eukaryotic cells, whereas bacterial cells are classified as prokaryotic. Before discussing the criteria for determining whether a cell is prokaryotic or eukaryotic, let’s first examine how biologists study cells.

Microscopy

Cells vary in size. With few exceptions, individual cells cannot be seen with the naked eye, so scientists use microscopes (micro- = “small”; -scope = “to look at”) to study them. A microscope is an instrument that magnifies an object. Most photographs of cells are taken with a microscope, and these images can also be called micrographs.The optics of a microscope’s lenses change the orientation of the image that the user sees. A specimen that is right-side up and facing right on the microscope slide will appear upside-down and facing left when viewed through a microscope, and vice versa. Similarly, if the slide is moved left while looking through the microscope, it will appear to move right, and if moved down, it will seem to move up. This occurs because microscopes use two sets of lenses to magnify the image. Because of the manner by which light travels through the lenses, this system of two lenses produces an inverted image (binocular, or dissecting microscopes, work in a similar manner, but include an additional magnification system that makes the final image appear to be upright).

Light Microscopes

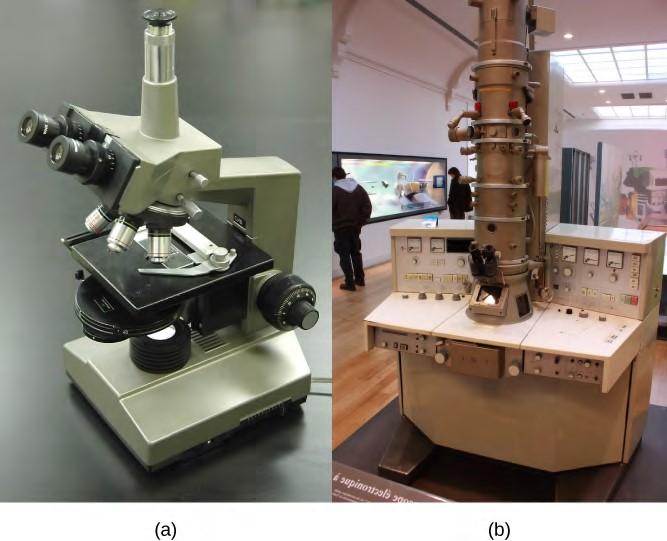

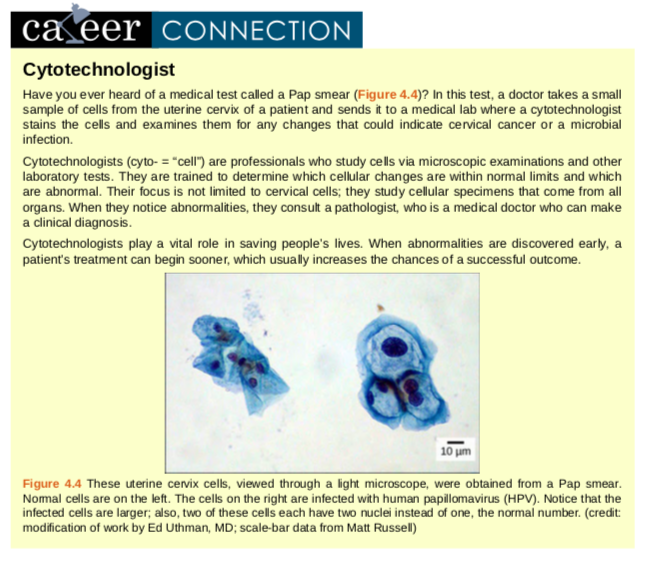

To give you a sense of cell size, a typical human red blood cell is about eight millionths of a meter or eight micrometers (abbreviated as eight μm) in diameter; the head of a pin of is about two thousandths of a meter (two mm) in diameter. That means about 250 red blood cells could fit on the head of a pin.Most student microscopes are classified as light microscopes (Figure 4.2a). Visible light passes and is bent through the lens system to enable the user to see the specimen. Light microscopes are advantageous for viewing living organisms, but since individual cells are generally transparent, their components are not distinguishable unless they are colored with special stains. Staining, however, usually kills the cells.Light microscopes commonly used in the undergraduate college laboratory magnify up to approximately 400 times. Two parameters that are important in microscopy are magnification and resolving power. Magnification is the process of enlarging an object in appearance. Resolving power is the ability of a microscope to distinguish two adjacent structures as separate: the higher the resolution, the better the clarity and detail of the image. When oil immersion lenses are used for the study of small objects, magnification is usually increased to 1,000 times. In order to gain a better understanding of cellular structure and function, scientists typically use electron microscopes.

Figure 4.2 (a) Most light microscopes used in a college biology lab can magnify cells up to approximately 400 times and have a resolution of about 200 nanometers. (b) Electron microscopes provide a much higher magnification, 100,000x, and a have a resolution of 50 picometers. (credit a: modification of work by “GcG”/Wikimedia Commons; credit b: modification of work by Evan Bench)

Electron Microscopes

In contrast to light microscopes, electron microscopes (Figure 4.2b) use a beam of electrons instead of a beam of light. Not only does this allow for higher magnification and, thus, more detail (Figure 4.3), it also provides higher resolving power. The method used to prepare the specimen for viewing with an electron microscope kills the specimen. Electrons have short wavelengths (shorter than photons) that move best in a vacuum, so living cells cannot be viewed with an electron microscope. In a scanning electron microscope, a beam of electrons moves back and forth across a cell’s surface, creating details of cell surface characteristics. In a transmission electron microscope, the electron beam penetrates the cell and provides details of a cell’s internal structures. As you might imagine, electron microscopes are significantly more bulky and expensive than light microscopes.

(a)(b)

Figure 4.3 (a) These Salmonella bacteria appear as tiny purple dots when viewed with a light microscope. (b) This scanning electron microscope micrograph shows Salmonella bacteria (in red) invading human cells (yellow). Even though subfigure (b) shows a different Salmonella specimen than subfigure (a), you can still observe the comparative increase in magnification and detail. (credit a: modification of work by CDC/Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Charles N. Farmer, Rocky Mountain Laboratories; credit b: modification of work by NIAID, NIH; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

For another perspective on cell size, try the How Big interactive at this site(http://openstaxcollege.org/l/cell_sizes) .

Cell Theory

The microscopes we use today are far more complex than those used in the 1600s by Antony van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch shopkeeper who had great skill in crafting lenses. Despite the limitations of his now-ancient lenses, van Leeuwenhoek observed the movements of protista (a type of single-celled organism) and sperm, which he collectively termed “animalcules.” In a 1665 publication called Micrographia, experimental scientist Robert Hooke coined the term “cell” for the box-like structures he observed when viewing cork tissue through a lens. In the 1670s, van Leeuwenhoek discovered bacteria and protozoa. Later advances in lenses, microscope construction, and staining techniques enabled other scientists to see some components inside cells. By the late 1830s, botanist Matthias Schleiden and zoologist Theodor Schwann were studying tissues and proposed the unified cell theory, which states that all living things are composed of one or more cells, the cell is the basic unit of life, and new cells arise from existing cells. Rudolf Virchow later made important contributions to this theory.

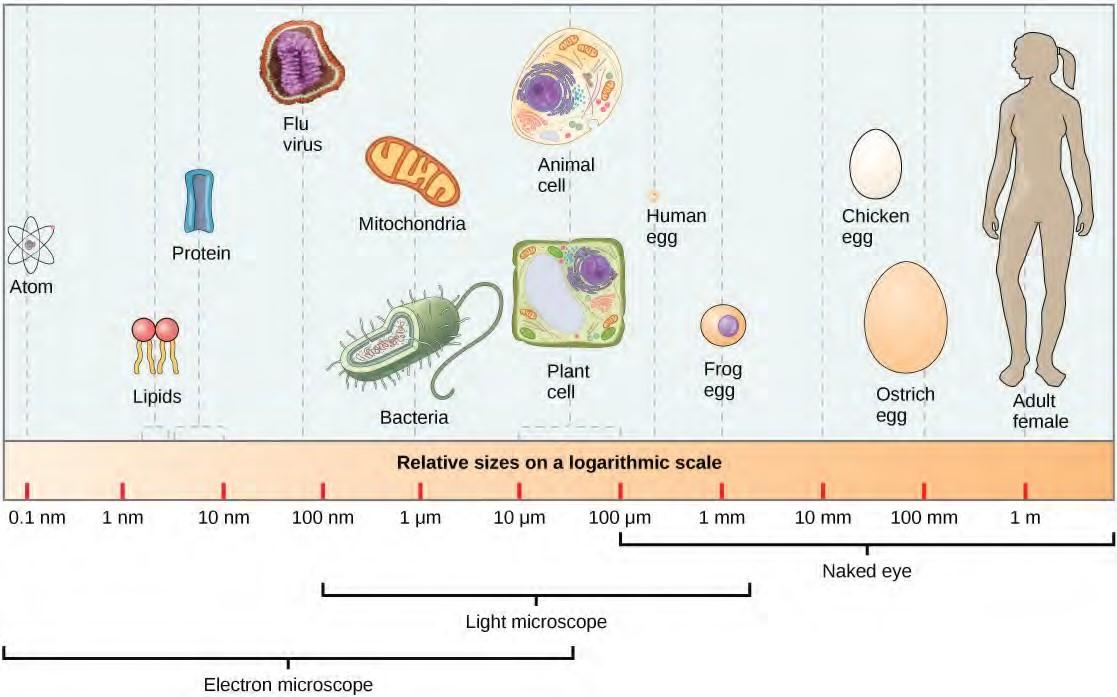

4.2 | Prokaryotic Cells

Cells fall into one of two broad categories: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. Only the predominantly single celled organisms of the domains Bacteria and Archaea are classified as prokaryotes (pro- = “before”; -kary- = “nucleus”). Cells of animals, plants, fungi, and protists are all eukaryotes (ceu- = “true”) and are made up of eukaryotic cells.

Components of Prokaryotic Cells

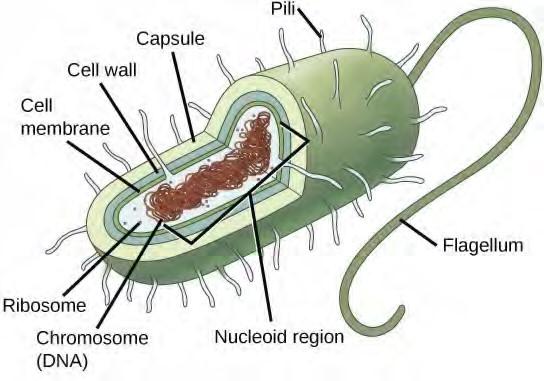

All cells share four common components: 1) a plasma membrane, an outer covering that separates the cell’s interior from its surrounding environment; 2) cytoplasm, consisting of a jelly-like cytosol within the cell in which other cellular components are found; 3) DNA, the genetic material of the cell; and 4) ribosomes, which synthesize proteins. However, prokaryotes differ from eukaryotic cells in several ways. A prokaryote is a simple, mostly single-celled (unicellular) organism that lacks a nucleus, or any other membrane-bound organelle. We will shortly come to see that this is significantly different in eukaryotes. Prokaryotic DNA is found in a central part of the cell: the nucleoid (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 This figure shows the generalized structure of a prokaryotic cell. All prokaryotes have chromosomal DNA localized in a nucleoid, ribosomes, a cell membrane, and a cell wall. The other structures shown are present in some, but not all, bacteria.

Most prokaryotes have a peptidoglycan cell wall and many have a polysaccharide capsule (Figure 4.5). The cell wall acts as an extra layer of protection, helps the cell maintain its shape, and prevents dehydration. The capsule enables the cell to attach to surfaces in its environment. Some prokaryotes have flagella, pili, or fimbriae. Flagella are used for locomotion. Pili are used to exchange genetic material during a type of reproduction called conjugation. Fimbriae are used by bacteria to attach to a host cell.

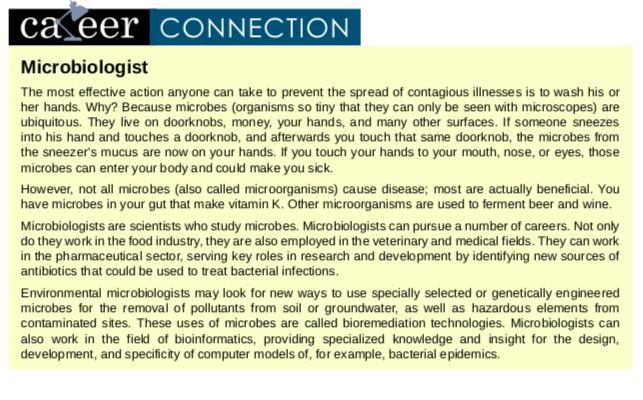

Cell Size

At 0.1 to 5.0 μm in diameter, prokaryotic cells are significantly smaller than eukaryotic cells, which have diameters ranging from 10 to 100 μm (Figure 4.6). The small size of prokaryotes allows ions and organic molecules that enter them to quickly diffuse to other parts of the cell. Similarly, any wastes produced within a prokaryotic cell can quickly diffuse out. This is not the case in eukaryotic cells, which have developed different structural adaptations to enhance intracellular transport.

Figure 4.6 This figure shows relative sizes of microbes on a logarithmic scale (recall that each unit of increase in a logarithmic scale represents a 10-fold increase in the quantity being measured).

Small size, in general, is necessary for all cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic. Let’s examine why that is so. First, we’ll consider the area and volume of a typical cell. Not all cells are spherical in shape, but most tend to approximate a sphere. You may remember from your high school geometry course that the formula for the surface area of a sphere is 4πr2, while the formula for its volume is 4πr3/3. Thus, as the radius of a cell increases, its surface area increases as the square of its radius, but its volume increases as the cube of its radius (much more rapidly). Therefore, as a cell increases in size, its surface area-to-volume ratio decreases. This same principle would apply if the cell had the shape of a cube (Figure 4.7). If the cell grows too large, the plasma membrane will not have sufficient surface area to support the rate of diffusion required for the increased volume. In other words, as a cell grows, it becomes less efficient. One way to become more efficient is to divide; another way is to develop organelles that perform specific tasks. These adaptations lead to the development of more sophisticated cells called eukaryotic cells.

4.3 | Eukaryotic Cells

Have you ever heard the phrase “form follows function?” It’s a philosophy practiced in many industries. In architecture, this means that buildings should be constructed to support the activities that will be carried out inside them. For example, a skyscraper should be built with several elevator banks; a hospital should be built so that its emergency room is easily accessible.

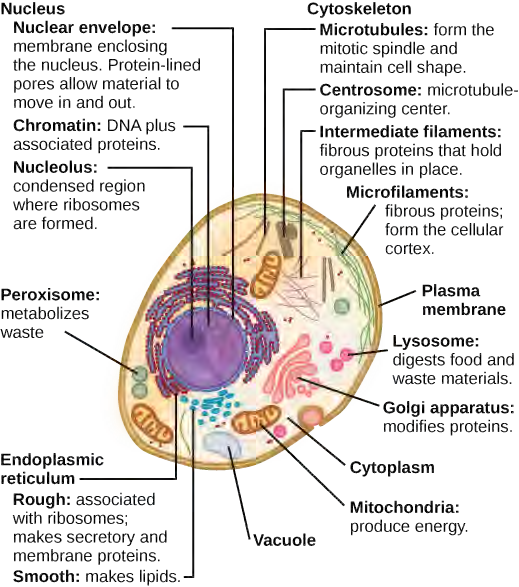

At this point, it should be clear to you that eukaryotic cells have a more complex structure than prokaryotic cells. Organelles allow different functions to be compartmentalized in different areas of the cell. Before turning to organelles, let’s first examine two important components of the cell: the plasma membrane and the cytoplasm.

The Plasma Membrane

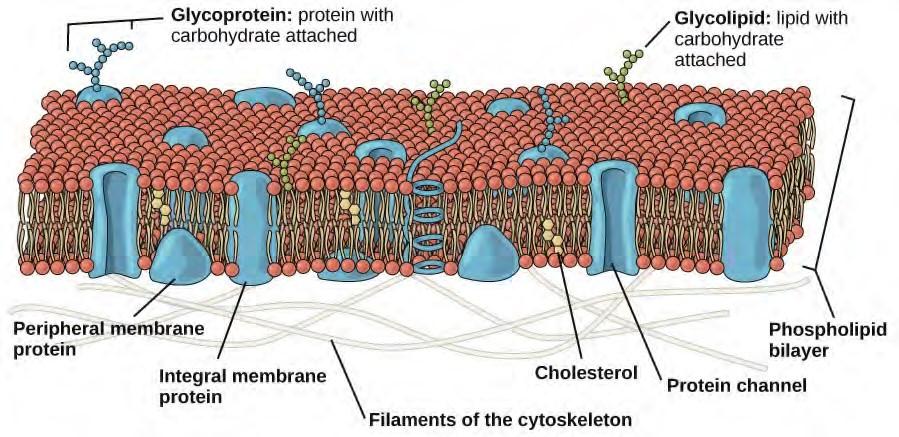

Like prokaryotes, eukaryotic cells have a plasma membrane ( Figure 4.9), a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins that separates the internal contents of the cell from its surrounding environment. A phospholipid is a lipid molecule with two fatty acid chains and a phosphate-containing group. The plasma membrane controls the passage of organic molecules, ions, water, and oxygen into and out of the cell. Wastes (such as carbon dioxide and ammonia) also leave the cell by passing through the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.9 The eukaryotic plasma membrane is a phospholipid bilayer with proteins and cholesterol embedded in it.

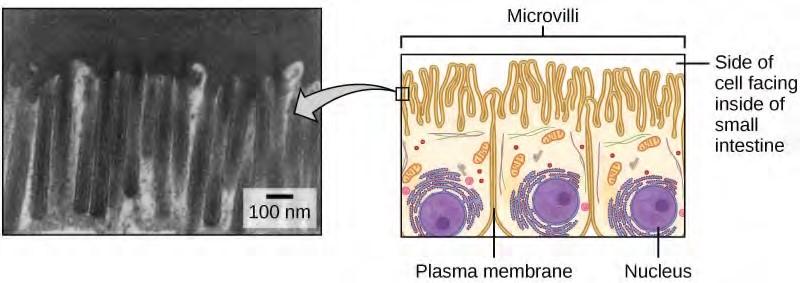

The plasma membranes of cells that specialize in absorption are folded into fingerlike projections called microvilli (singular = microvillus); ( Figure 4.10). Such cells are typically found lining the small intestine, the organ that absorbs nutrients from digested food. This is an excellent example of form following function. People with celiac disease have an immune response to gluten, which is a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. The immune response damages microvilli, and thus, afflicted individuals cannot absorb nutrients. This leads to malnutrition, cramping, and diarrhea. Patients suffering from celiac disease must follow a gluten-free diet.

Figure 4.10 Microvilli, shown here as they appear on cells lining the small intestine, increase the surface area available for absorption. These microvilli are only found on the area of the plasma membrane that faces the cavity from which substances will be absorbed. (credit “micrograph”: modification of work by Louisa Howard)

The Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is the entire region of a cell between the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope (a structure to be discussed shortly). It is made up of organelles suspended in the gel-like cytosol, the cytoskeleton, and various chemicals ( Figure 4.8). Even though the cytoplasm consists of 70 to 80 percent water, it has a semi-solid consistency, which comes from the proteins within it. However, proteins are not the only organic molecules found in the cytoplasm. Glucose and other simple sugars, polysaccharides, amino acids, nucleic acids, fatty acids, and derivatives of glycerol are found there, too. Ions of sodium, potassium, calcium, and many other elements are also dissolved in the cytoplasm. Many metabolic reactions, including protein synthesis, take place in the cytoplasm.

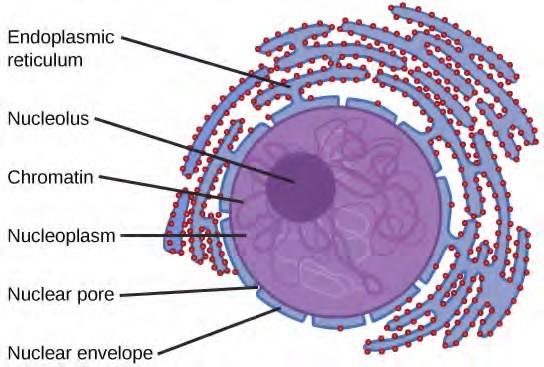

The Nucleus

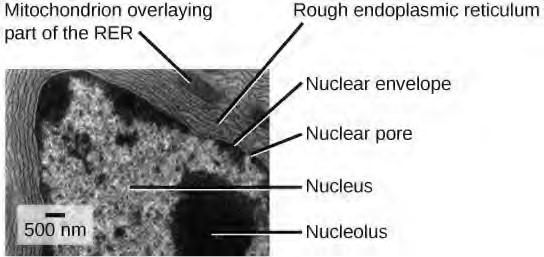

Typically, the nucleus is the most prominent organelle in a cell ( Figure 4.8). The nucleus (plural = nuclei) houses the cell’s DNA and directs the synthesis of ribosomes and proteins. Let’s look at it in more detail ( Figure 4.11).

Figure 4.11 The nucleus stores chromatin (DNA plus proteins) in a gel-like substance called the nucleoplasm. The nucleolus is a condensed region of chromatin where ribosome synthesis occurs. The boundary of the nucleus is called the nuclear envelope. It consists of two phospholipid bilayers: an outer membrane and an inner membrane. The nuclear membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum. Nuclear pores allow substances to enter and exit the nucleus.

The Nuclear Envelope

The nuclear envelope is a double-membrane structure that constitutes the outermost portion of the nucleus ( Figure 4.11). Both the inner and outer membranes of the nuclear envelope are phospholipid bilayers.The nuclear envelope is punctuated with pores that control the passage of ions, molecules, and RNA between the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm. The nucleoplasm is the semi-solid fluid inside the nucleus, where we find the chromatin and the nucleolus.

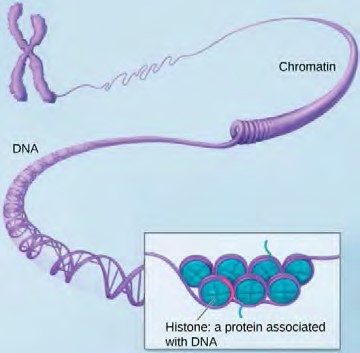

Chromatin and Chromosomes

To understand chromatin, it is helpful to first consider chromosomes. Chromosomes are structures within the nucleus that are made up of DNA, the hereditary material. You may remember that in prokaryotes, DNA is organized into a single circular chromosome. In eukaryotes, chromosomes are linear structures. Every eukaryotic species has a specific number of chromosomes in the nuclei of its body’s cells. For example, in humans, the chromosome number is 46, while in fruit flies, it is eight. Chromosomes are only visible and distinguishable from one another when the cell is getting ready to divide. When the cell is in the growth and maintenance phases of its life cycle, proteins are attached to chromosomes, and they resemble an unwound, jumbled bunch of threads. These unwound protein chromosome complexes are called chromatin ( Figure 4.12); chromatin describes the material that makes up the chromosomes both when condensed and decondensed.

(a)(b)Figure 4.12 (a) This image shows various levels of the organization of chromatin (DNA and protein). (b) This image shows paired chromosomes. (credit b: modification of work by NIH; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

The Nucleolus

We already know that the nucleus directs the synthesis of ribosomes, but how does it do this? Some chromosomes have sections of DNA that encode ribosomal RNA. A darkly staining area within the nucleus called the nucleolus (plural = nucleoli) aggregates the ribosomal RNA with associated proteins to assemble the ribosomal subunits that are then transported out through the pores in the nuclear envelope to the cytoplasm.

Ribosomes

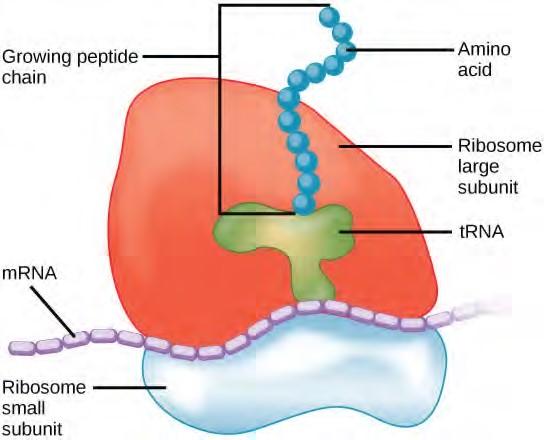

Ribosomes are the cellular structures responsible for protein synthesis. When viewed through an electron microscope, ribosomes appear either as clusters (polyribosomes) or single, tiny dots that float freely in the cytoplasm. They may be attached to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane or the cytoplasmic side of the endoplasmic reticulum and the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope ( Figure 4.8). Electron microscopy has shown us that ribosomes, which are large complexes of protein and RNA, consist of two subunits, aptly called large and small ( Figure 4.13). Ribosomes receive their “orders” for protein synthesis from the nucleus where the DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA travels to the ribosomes, which translate the code provided by the sequence of the nitrogenous bases in the mRNA into a specific order of amino acids in a protein. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins.

Figure 4.13 Ribosomes are made up of a large subunit (top) and a small subunit (bottom). During protein synthesis, ribosomes assemble amino acids into proteins.

Because protein synthesis is an essential function of all cells (including enzymes, hormones, antibodies, pigments, structural components, and surface receptors), ribosomes are found in practically every cell. Ribosomes are particularly abundant in cells that synthesize large amounts of protein. For example, the pancreas is responsible for creating several digestive enzymes and the cells that produce these enzymes contain many ribosomes. Thus, we see another example of form following function.

Mitochondria

Mitochondria (singular = mitochondrion) are often called the “powerhouses” or “energy factories” of a cell because they are responsible for making adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy carrying molecule. ATP represents the short-term stored energy of the cell. Cellular respiration is the process of making ATP using the chemical energy found in glucose and other nutrients. In mitochondria, this process uses oxygen and produces carbon dioxide as a waste product. In fact, the carbon dioxide that you exhale with every breath comes from the cellular reactions that produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

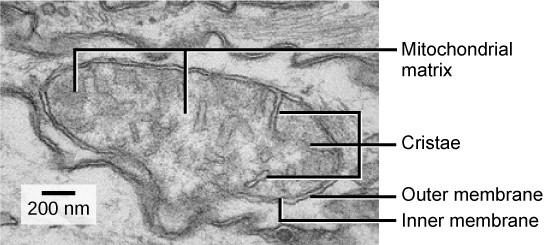

Mitochondria are oval-shaped, double membrane organelles ( Figure 4.14) that have their own ribosomes and DNA. Each membrane is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins. The inner layer has folds called cristae. The area surrounded by the folds is called the mitochondrial matrix. The cristae and the matrix have different roles in cellular respiration.

Figure 4.14 This electron micrograph shows a mitochondrion as viewed with a transmission electron microscope. This organelle has an outer membrane and an inner membrane. The inner membrane contains folds, called cristae, which increase its surface area. The space between the two membranes is called the intermembrane space, and the space inside the inner membrane is called the mitochondrial matrix. ATP synthesis takes place on the inner membrane. (credit: modification of work by Matthew Britton; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes are small, round organelles enclosed by single membranes. They carry out oxidation reactions that break down fatty acids and amino acids. They also detoxify many poisons that may enter the body. (Many of these oxidation reactions release hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, which would be damaging to cells; however, when these reactions are confined to peroxisomes, enzymes safely break down the H2O2 into oxygen and water.) For example, alcohol is detoxified by peroxisomes in liver cells. Glyoxysomes, which are specialized peroxisomes in plants, are responsible for converting stored fats into sugars.

Vesicles and Vacuoles

Vesicles and vacuoles are membrane-bound sacs that function in storage and transport. Other than the fact that vacuoles are somewhat larger than vesicles, there is a very subtle distinction between them: The membranes of vesicles can fuse with either the plasma membrane or other membrane systems within the cell. Additionally, some agents such as enzymes within plant vacuoles break down macromolecules. The membrane of a vacuole does not fuse with the membranes of other cellular components.

Animal Cells versus Plant Cells

At this point, you know that each eukaryotic cell has a plasma membrane, cytoplasm, a nucleus, ribosomes, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and in some, vacuoles, but there are some striking differences between animal and plant cells. While both animal and plant cells have microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs), animal cells also have centrioles associated with the MTOC: a complex called the centrosome. Animal cells each have a centrosome and lysosomes, whereas plant cells do not. Plant cells have a cell wall, chloroplasts and other specialized plastids, and a large central vacuole, whereas animal cells do not.

The Centrosome

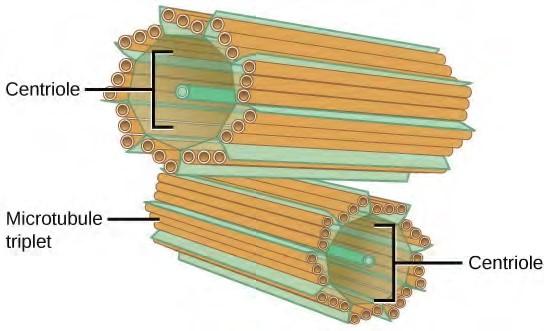

The centrosome is a microtubule-organizing center found near the nuclei of animal cells. It contains a pair of centrioles, two structures that lie perpendicular to each other ( Figure 4.15). Each centriole is a cylinder of nine triplets of microtubules.

Figure 4.15 The centrosome consists of two centrioles that lie at right angles to each other. Each centriole is a cylinder made up of nine triplets of microtubules. Non-tubulin proteins (indicated by the green lines) hold the microtubule triplets together.

The centrosome (the organelle where all microtubules originate) replicates itself before a cell divides, and the centrioles appear to have some role in pulling the duplicated chromosomes to opposite ends of the dividing cell. However, the exact function of the centrioles in cell division isn’t clear, because cells that have had the centrosome removed can still divide, and plant cells, which lack centrosomes, are capable of cell division.

Lysosomes

Animal cells have another set of organelles not found in plant cells: lysosomes. The lysosomes are the cell’s “garbage disposal.” In plant cells, the digestive processes take place in vacuoles. Enzymes within the lysosomes aid the breakdown of proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles. These enzymes are active at a much lower pH than that of the cytoplasm. Therefore, the pH within lysosomes is more acidic than the pH of the cytoplasm. Many reactions that take place in the cytoplasm could not occur at a low pH, so again, the advantage of compartmentalizing the eukaryotic cell into organelles is apparent.

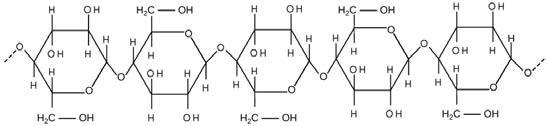

The Cell Wall

If you examine Figure 4.8b, the diagram of a plant cell, you will see a structure external to the plasma membrane called the cell wall. The cell wall is a rigid covering that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell. Fungal and protistan cells also have cell walls. While the chief component of prokaryotic cell walls is peptidoglycan, the major organic molecule in the plant cell wall is cellulose ( Figure 4.16), a polysaccharide made up of glucose units. Have you ever noticed that when you bite into a raw vegetable, like celery, it crunches? That’s because you are tearing the rigid cell walls of the celery cells with your teeth.

Figure 4.16 Cellulose is a long chain of β-glucose molecules connected by a 1-4 linkage. The dashed lines at each end of the figure indicate a series of many more glucose units. The size of the page makes it impossible to portray an entire cellulose molecule.

Chloroplasts

Like the mitochondria, chloroplasts have their own DNA and ribosomes, but chloroplasts have an entirely different function. Chloroplasts are plant cell organelles that carry out photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is the series of reactions that use carbon dioxide, water, and light energy to make glucose and oxygen. This is a major difference between plants and animals; plants (autotrophs) are able to make their own food, like sugars, while animals (heterotrophs) must ingest their food.

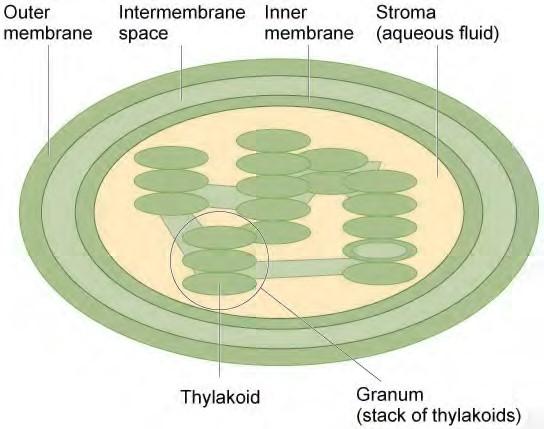

Like mitochondria, chloroplasts have outer and inner membranes, but within the space enclosed by a chloroplast’s inner membrane is a set of interconnected and stacked fluid-filled membrane sacs called thylakoids ( Figure 4.17). Each stack of thylakoids is called a granum (plural = grana). The fluid enclosed by the inner membrane that surrounds the grana is called the stroma.

Figure 4.17 The chloroplast has an outer membrane, an inner membrane, and membrane structures called thylakoids that are stacked into grana. The space inside the thylakoid membranes is called the thylakoid space. The light harvesting reactions take place in the thylakoid membranes, and the synthesis of sugar takes place in the fluid inside the inner membrane, which is called the stroma. Chloroplasts also have their own genome, which is contained on a single circular chromosome.

The chloroplasts contain a green pigment called chlorophyll, which captures the light energy that drives the reactions of photosynthesis. Like plant cells, photosynthetic protists also have chloroplasts. Some bacteria perform photosynthesis, but their chlorophyll is not relegated to an organelle.

The Central Vacuole

Previously, we mentioned vacuoles as essential components of plant cells. If you look at Figure 4.8b, you will see that plant cells each have a large central vacuole that occupies most of the area of the cell. The central vacuole plays a key role in regulating the cell’s concentration of water in changing environmental conditions. Have you ever noticed that if you forget to water a plant for a few days, it wilts? That’s because as the water concentration in the soil becomes lower than the water concentration in the plant, water moves out of the central vacuoles and cytoplasm. As the central vacuole shrinks, it leaves the cell wall unsupported. This loss of support to the cell walls of plant cells results in the wilted appearance of the plant.

The central vacuole also supports the expansion of the cell. When the central vacuole holds more water, the cell gets larger without having to invest a lot of energy in synthesizing new cytoplasm.

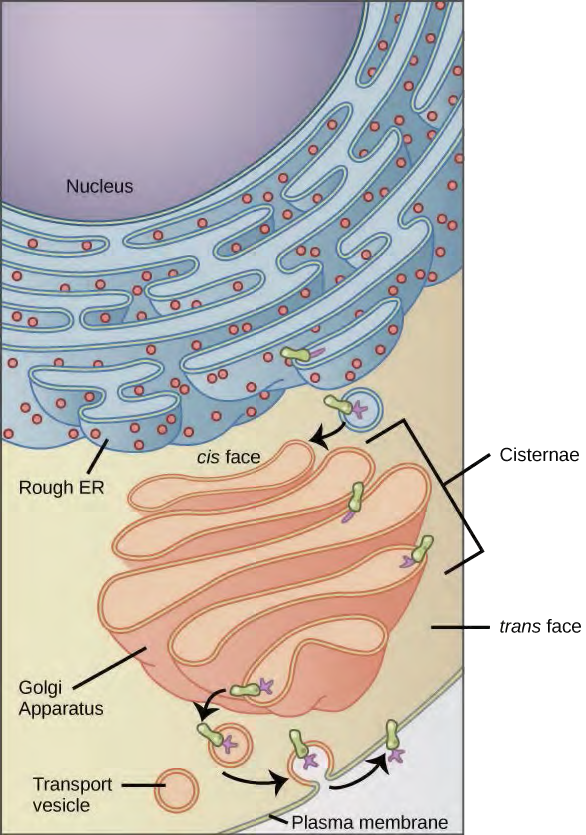

4.4 | The Endomembrane System and Proteins

The endomembrane system (endo = “within”) is a group of membranes and organelles (Figure 4.18) in eukaryotic cells that works together to modify, package, and transport lipids and proteins. It includes the nuclear envelope, lysosomes, and vesicles, which we’ve already mentioned, and the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, which we will cover shortly. Although not technically within the cell, the plasma membrane is included in the endomembrane system because, as you will see, it interacts with the other endomembranous organelles. The endomembrane system does not include the membranes of either mitochondria or chloroplasts.

The Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 4.18) is a series of interconnected membranous sacs and tubules that collectively modifies proteins and synthesizes lipids. However, these two functions are performed in separate areas of the ER: the rough ER and the smooth ER, respectively.

The hollow portion of the ER tubules is called the lumen or cisternal space. The membrane of the ER, which is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins, is continuous with the nuclear envelope.

Rough ER

The rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) is so named because the ribosomes attached to its cytoplasmic surface give it a studded appearance when viewed through an electron microscope (Figure 4.19).

Figure 4.19 This transmission electron micrograph shows the rough endoplasmic reticulum and other organelles in a pancreatic cell. (credit: modification of work by Louisa Howard)

Ribosomes transfer their newly synthesized proteins into the lumen of the RER where they undergo structural modifications, such as folding or the acquisition of side chains. These modified proteins will be incorporated into cellular membranes—the membrane of the ER or those of other organelles—or secreted from the cell (such as protein hormones, enzymes). The RER also makes phospholipids for cellular membranes.

If the phospholipids or modified proteins are not destined to stay in the RER, they will reach their destinations via transport vesicles that bud from the RER’s membrane (Figure 4.18).

Since the RER is engaged in modifying proteins (such as enzymes, for example) that will be secreted from the cell, you would be correct in assuming that the RER is abundant in cells that secrete proteins.

This is the case with cells of the liver, for example.

Smooth ER

The smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) is continuous with the RER but has few or no ribosomes on its cytoplasmic surface (Figure 4.18). Functions of the SER include synthesis of carbohydrates, lipids, and steroid hormones; detoxification of medications and poisons; and storage of calcium ions.

In muscle cells, a specialized SER called the sarcoplasmic reticulum is responsible for storage of the calcium ions that are needed to trigger the coordinated contractions of the muscle cells.

You can watch an excellent animation of the endomembrane system here (http://openstaxcollege.org/ l/endomembrane) . At the end of the animation, there is a short self-assessment.

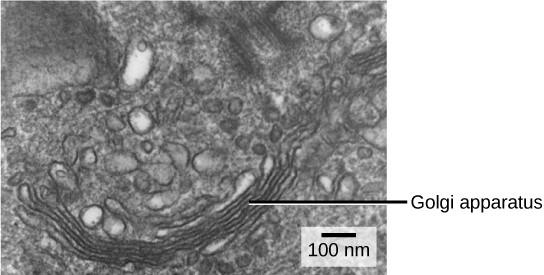

The Golgi Apparatus

We have already mentioned that vesicles can bud from the ER and transport their contents elsewhere, but where do the vesicles go? Before reaching their final destination, the lipids or proteins within the transport vesicles still need to be sorted, packaged, and tagged so that they wind up in the right place. Sorting, tagging, packaging, and distribution of lipids and proteins takes place in the Golgi apparatus (also called the Golgi body), a series of flattened membranes (Figure 4.20).

Figure 4.20 The Golgi apparatus in this white blood cell is visible as a stack of semicircular, flattened rings in the lower portion of the image. Several vesicles can be seen near the Golgi apparatus. (credit: modification of work by Louisa Howard)

The receiving side of the Golgi apparatus is called the cis face. The opposite side is called the trans face. The transport vesicles that formed from the ER travel to the cis face, fuse with it, and empty their contents into the lumen of the Golgi apparatus. As the proteins and lipids travel through the Golgi, they undergo further modifications that allow them to be sorted. The most frequent modification is the addition of short chains of sugar molecules. These newly modified proteins and lipids are then tagged with phosphate groups or other small molecules so that they can be routed to their proper destinations.

Finally, the modified and tagged proteins are packaged into secretory vesicles that bud from the trans face of the Golgi. While some of these vesicles deposit their contents into other parts of the cell where they will be used, other secretory vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents outside the cell.

In another example of form following function, cells that engage in a great deal of secretory activity (such as cells of the salivary glands that secrete digestive enzymes or cells of the immune system that secrete antibodies) have an abundance of Golgi.

In plant cells, the Golgi apparatus has the additional role of synthesizing polysaccharides, some of which are incorporated into the cell wall and some of which are used in other parts of the cell.

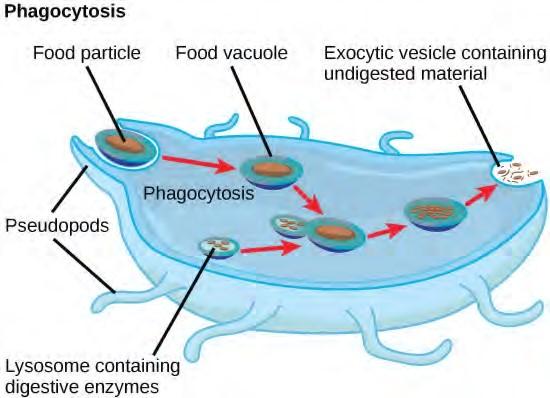

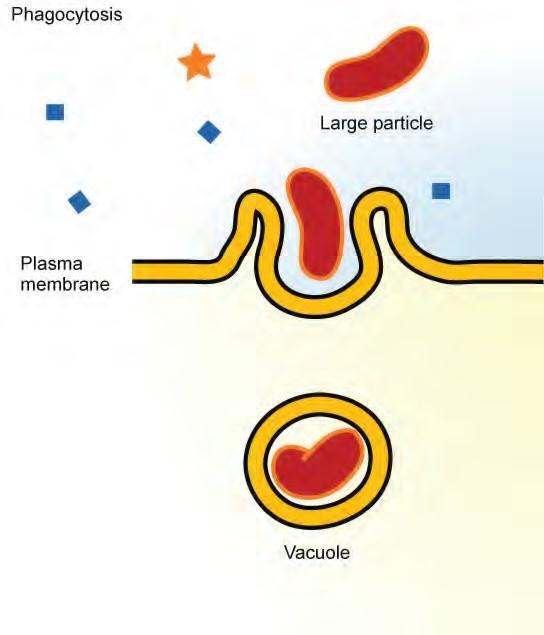

Lysosomes

In addition to their role as the digestive component and organelle-recycling facility of animal cells, lysosomes are considered to be parts of the endomembrane system. Lysosomes also use their hydrolytic enzymes to destroy pathogens (disease-causing organisms) that might enter the cell. A good example of this occurs in a group of white blood cells called macrophages, which are part of your body’s immune system. In a process known as phagocytosis or endocytosis, a section of the plasma membrane of the macrophage invaginates (folds in) and engulfs a pathogen. The invaginated section, with the pathogen inside, then pinches itself off from the plasma membrane and becomes a vesicle. The vesicle fuses with a lysosome. The lysosome’s hydrolytic enzymes then destroy the pathogen (Figure 4.21).

Figure 4.21 A macrophage has engulfed (phagocytized) a potentially pathogenic bacterium and then fuses with a lysosomes within the cell to destroy the pathogen. Other organelles are present in the cell but for simplicity are not shown.

4.5 | The Cytoskeleton

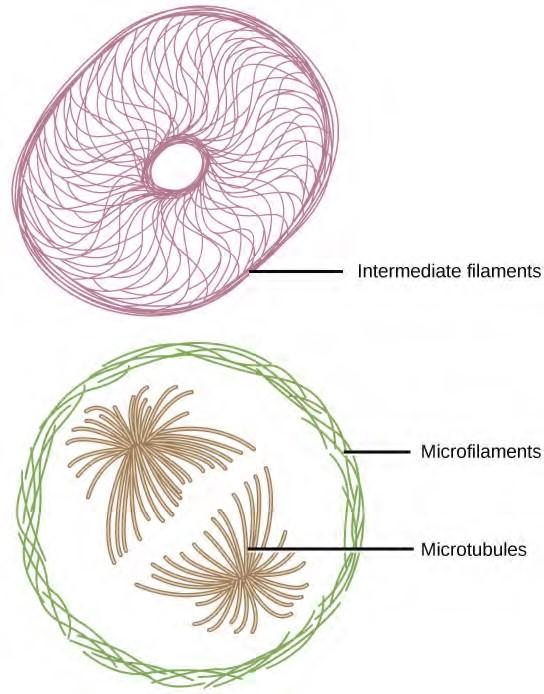

If you were to remove all the organelles from a cell, would the plasma membrane and the cytoplasm be the only components left? No. Within the cytoplasm, there would still be ions and organic molecules, plus a network of protein fibers that help maintain the shape of the cell, secure some organelles in specific positions, allow cytoplasm and vesicles to move within the cell, and enable cells within multicellular organisms to move. Collectively, this network of protein fibers is known as the cytoskeleton. There are three types of fibers within the cytoskeleton: microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules (Figure 4.22). Here, we will examine each.

Figure 4.22 Microfilaments thicken the cortex around the inner edge of a cell; like rubber bands, they resist tension. Microtubules are found in the interior of the cell where they maintain cell shape by resisting compressive forces. Intermediate filaments are found throughout the cell and hold organelles in place.

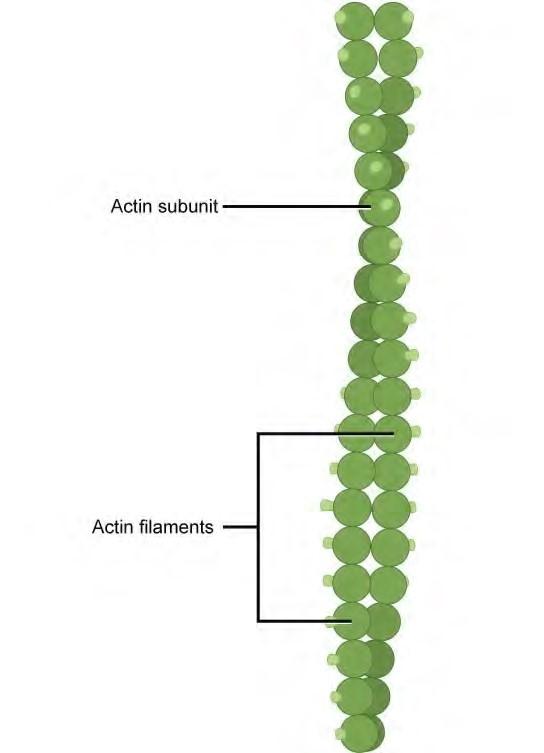

Microfilaments

Of the three types of protein fibers in the cytoskeleton, microfilaments are the narrowest. They function in cellular movement, have a diameter of about 7 nm, and are made of two intertwined strands of a globular protein called actin (Figure 4.23). For this reason, microfilaments are also known as actin filaments.

Figure 4.23 Microfilaments are made of two intertwined strands of actin.

Actin is powered by ATP to assemble its filamentous form, which serves as a track for the movement of a motor protein called myosin. This enables actin to engage in cellular events requiring motion, such as cell division in animal cells and cytoplasmic streaming, which is the circular movement of the cell cytoplasm in plant cells. Actin and myosin are plentiful in muscle cells. When your actin and myosin filaments slide past each other, your muscles contract.

Microfilaments also provide some rigidity and shape to the cell. They can depolymerize (disassemble) and reform quickly, thus enabling a cell to change its shape and move. White blood cells (your body’s infection-fighting cells) make good use of this ability. They can move to the site of an infection and phagocytize the pathogen.

To see an example of a white blood cell in action, click here (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ chasing_bcteria) and watch a short time-lapse video of the cell capturing two bacteria. It engulfs one and then moves on to the other.

Intermediate Filaments

Intermediate filaments are made of several strands of fibrous proteins that are wound together (Figure 4.24). These elements of the cytoskeleton get their name from the fact that their diameter, 8 to 10 nm, is between those of microfilaments and microtubules.

Figure 4.24 Intermediate filaments consist of several intertwined strands of fibrous proteins.

Intermediate filaments have no role in cell movement. Their function is purely structural. They bear tension, thus maintaining the shape of the cell, and anchor the nucleus and other organelles in place. Figure 4.22 shows how intermediate filaments create a supportive scaffolding inside the cell.

The intermediate filaments are the most diverse group of cytoskeletal elements. Several types of fibrous proteins are found in the intermediate filaments. You are probably most familiar with keratin, the fibrous protein that strengthens your hair, nails, and the epidermis of the skin.

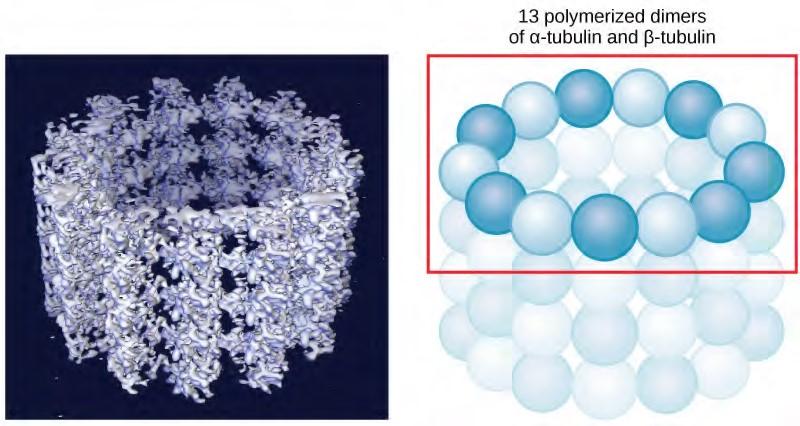

Microtubules

As their name implies, microtubules are small hollow tubes. The walls of the microtubule are made of polymerized dimers of α-tubulin and β-tubulin, two globular proteins (Figure 4.25). With a diameter of about 25 nm, microtubules are the widest components of the cytoskeleton. They help the cell resist compression, provide a track along which vesicles move through the cell, and pull replicated chromosomes to opposite ends of a dividing cell. Like microfilaments, microtubules can dissolve and reform quickly.

Figure 4.25 Microtubules are hollow. Their walls consist of 13 polymerized dimers of α-tubulin and β-tubulin (right image). The left image shows the molecular structure of the tube.

Microtubules are also the structural elements of flagella, cilia, and centrioles (the latter are the two perpendicular bodies of the centrosome). In fact, in animal cells, the centrosome is the microtubule organizing center. In eukaryotic cells, flagella and cilia are quite different structurally from their counterparts in prokaryotes, as discussed below.

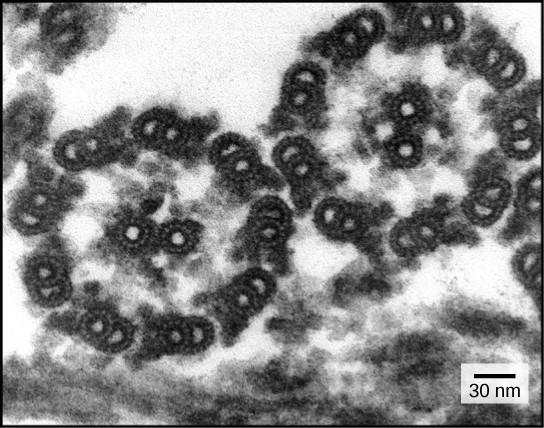

Flagella and Cilia

To refresh your memory, flagella (singular = flagellum) are long, hair-like structures that extend from the plasma membrane and are used to move an entire cell (for example, sperm, Euglena). When present, the cell has just one flagellum or a few flagella. When cilia (singular = cilium) are present, however, many of them extend along the entire surface of the plasma membrane. They are short, hair-like structures that are used to move entire cells (such as paramecia) or substances along the outer surface of the cell (for example, the cilia of cells lining the Fallopian tubes that move the ovum toward the uterus, or cilia lining the cells of the respiratory tract that trap particulate matter and move it toward your nostrils.)

Despite their differences in length and number, flagella and cilia share a common structural arrangement of microtubules called a “9 + 2 array.” This is an appropriate name because a single flagellum or cilium is made of a ring of nine microtubule doublets, surrounding a single microtubule doublet in the center (Figure 4.26).

Figure 4.26 This transmission electron micrograph of two flagella shows the 9 + 2 array of microtubules: nine microtubule doublets surround a single microtubule doublet. (credit: modification of work by Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility, Dartmouth College; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

You have now completed a broad survey of the components of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. For a summary of cellular components in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, see Table 4.1.

Components of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

|

Cell Component |

Present in Prokaryotes Function |

Present in Animal Cells? |

Present in Plant Cells? |

|

|

Plasma membrane |

Separates cell from external environment; controls passage of organic molecules, ions, water, oxygen, and wastes into and out of cell |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Cytoplasm |

Provides turgor pressure to plant cells as fluid inside the central vacuole; site of many metabolic reactions; medium in which organelles are found |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Nucleolus |

Darkened area within the nucleus where ribosomal subunits are synthesized. |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Nucleus |

Cell organelle that houses DNA and directs synthesis of ribosomes and proteins |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Ribosomes |

Protein synthesis |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mitochondria |

ATP production/cellular respiration |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Peroxisomes |

Oxidizes and thus breaks down fatty acids and amino acids, and detoxifies poisons |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Vesicles and vacuoles |

Storage and transport; digestive function in plant cells |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Centrosome |

Unspecified role in cell division in animal cells; source of microtubules in animal cells |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Lysosomes |

Digestion of macromolecules; recycling of worn-out organelles |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Cell wall |

Protection, structural support and maintenance of cell shape |

Yes, primarily peptidoglycan |

No |

Yes, primarily cellulose |

|

Chloroplasts |

Photosynthesis |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Endoplasmic reticulum |

Modifies proteins and synthesizes lipids |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Golgi apparatus |

Modifies, sorts, tags, packages, and distributes lipids and proteins |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Table 4.1

Components of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

|

Cell Component |

Function |

Present in Prokaryotes? |

Present in Animal Cells? |

Present in Plant Cells? |

|

Cytoskeleton |

Maintains cell’s shape, secures organelles in specific positions, allows cytoplasm and vesicles to move within cell, and enables unicellular organisms to move independently |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Flagella |

Cellular locomotion |

Some |

Some |

No, except for some plant sperm cells. |

|

Cilia |

Cellular locomotion, movement of particles along extracellular surface of plasma membrane, and filtration |

Some |

Some |

No |

Table 4.1

4.6 | Connections between Cells and Cellular Activities

You already know that a group of similar cells working together is called a tissue. As you might expect, if cells are to work together, they must communicate with each other, just as you need to communicate with others if you work on a group project. Let’s take a look at how cells communicate with each other.

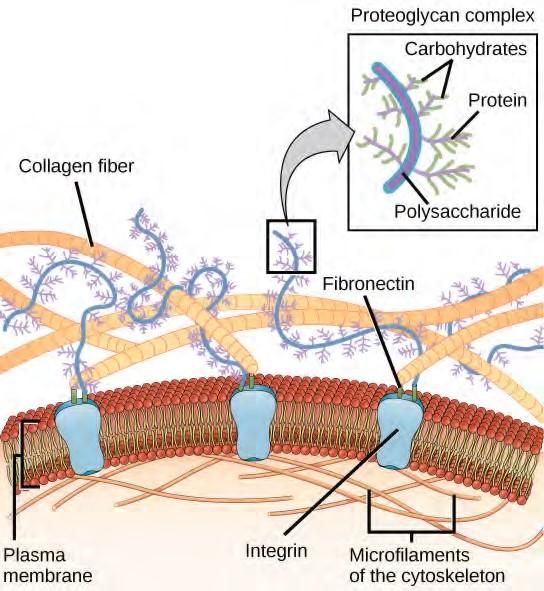

Extracellular Matrix of Animal Cells

Most animal cells release materials into the extracellular space. The primary components of these materials are proteins, and the most abundant protein is collagen. Collagen fibers are interwoven with carbohydrate-containing protein molecules called proteoglycans. Collectively, these materials are called the extracellular matrix (Figure 4.27). Not only does the extracellular matrix hold the cells together to form a tissue, but it also allows the cells within the tissue to communicate with each other. How can this happen?

Figure 4.27 The extracellular matrix consists of a network of proteins and carbohydrates.

Cells have protein receptors on the extracellular surfaces of their plasma membranes. When a molecule within the matrix binds to the receptor, it changes the molecular structure of the receptor. The receptor, in turn, changes the conformation of the microfilaments positioned just inside the plasma membrane. These conformational changes induce chemical signals inside the cell that reach the nucleus and turn “on” or “off” the transcription of specific sections of DNA, which affects the production of associated proteins, thus changing the activities within the cell.

Blood clotting provides an example of the role of the extracellular matrix in cell communication. When the cells lining a blood vessel are damaged, they display a protein receptor called tissue factor. When tissue factor binds with another factor in the extracellular matrix, it causes platelets to adhere to the wall of the damaged blood vessel, stimulates the adjacent smooth muscle cells in the blood vessel to contract (thus constricting the blood vessel), and initiates a series of steps that stimulate the platelets to produce clotting factors.

Intercellular Junctions

Cells can also communicate with each other via direct contact, referred to as intercellular junctions. There are some differences in the ways that plant and animal cells do this. Plasmodesmata are junctions between plant cells, whereas animal cell contacts include tight junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes.

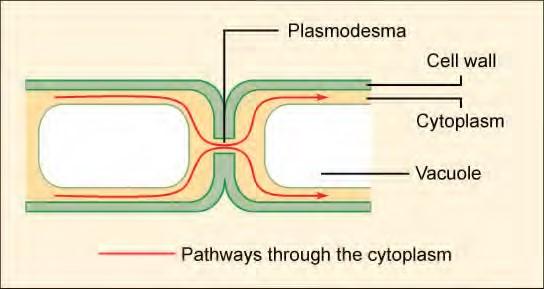

Plasmodesmata

In general, long stretches of the plasma membranes of neighboring plant cells cannot touch one another because they are separated by the cell wall that surrounds each cell (Figure 4.8b). How then, can a plant transfer water and other soil nutrients from its roots, through its stems, and to its leaves? Such transport uses the vascular tissues (xylem and phloem) primarily. There also exist structural modifications called plasmodesmata (singular = plasmodesma), numerous channels that pass between cell walls of adjacent plant cells, connect their cytoplasm, and enable materials to be transported from cell to cell, and thus throughout the plant (Figure 4.28).

Figure 4.28 A plasmodesma is a channel between the cell walls of two adjacent plant cells. Plasmodesmata allow materials to pass from the cytoplasm of one plant cell to the cytoplasm of an adjacent cell.

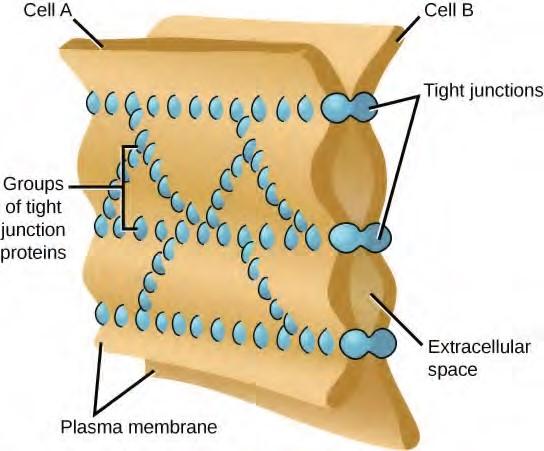

Tight Junctions

A tight junction is a watertight seal between two adjacent animal cells (Figure 4.29). The cells are held tightly against each other by proteins (predominantly two proteins called claudins and occludins).

Figure 4.29 Tight junctions form watertight connections between adjacent animal cells. Proteins create tight junction adherence. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

This tight adherence prevents materials from leaking between the cells; tight junctions are typically found in epithelial tissues that line internal organs and cavities, and comprise most of the skin. For example, the tight junctions of the epithelial cells lining your urinary bladder prevent urine from leaking out into the extracellular space.

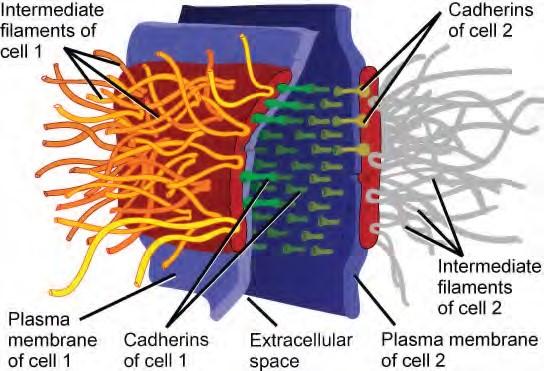

Desmosomes

Also found only in animal cells are desmosomes, which act like spot welds between adjacent epithelial cells (Figure 4.30). Short proteins called cadherins in the plasma membrane connect to intermediate filaments to create desmosomes. The cadherins join two adjacent cells together and maintain the cells in a sheet-like formation in organs and tissues that stretch, like the skin, heart, and muscles.

Figure 4.30 A desmosome forms a very strong spot weld between cells. It is created by the linkage

of cadherins and intermediate filaments. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

Gap Junctions

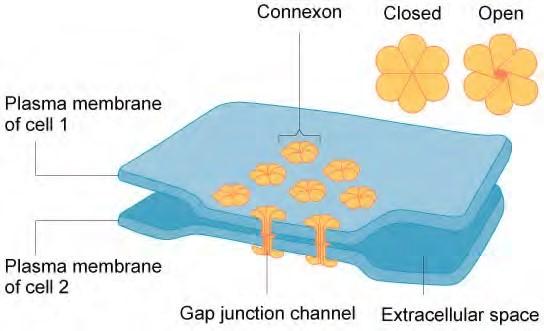

Gap junctions in animal cells are like plasmodesmata in plant cells in that they are channels between adjacent cells that allow for the transport of ions, nutrients, and other substances that enable cells to communicate (Figure 4.31). Structurally, however, gap junctions and plasmodesmata differ.

Figure 4.31 A gap junction is a protein-lined pore that allows water and small molecules to pass between adjacent animal cells. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

Gap junctions develop when a set of six proteins (called connexins) in the plasma membrane arrange themselves in an elongated donut-like configuration called a connexon. When the pores (“doughnut holes”) of connexons in adjacent animal cells align, a channel between the two cells forms. Gap junctions are particularly important in cardiac muscle: The electrical signal for the muscle to contract is passed efficiently through gap junctions, allowing the heart muscle cells to contract in tandem.

To conduct a virtual microscopy lab and review the parts of a cell, work through the steps of this interactive assignment (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/microscopy_lab) .

Figure 4.32 Despite its seeming hustle and bustle, Grand Central Station functions with a high level of organization: People and objects move from one location to another, they cross or are contained within certain boundaries, and they provide a constant flow as part of larger activity. Analogously, a plasma membrane’s functions involve movement within the cell and across boundaries in the process of intracellular and intercellular activities. (credit: modification of work by Randy Le’Moine)

4.7 | Plasma Membrane Components and Structure

A cell’s plasma membrane defines the cell, outlines its borders, and determines the nature of its interaction with its environment (see Table 4.2 for a summary). Cells exclude some substances, take in others, and excrete still others, all in controlled quantities. The plasma membrane must be very flexible to allow certain cells, such as red blood cells and white blood cells, to change shape as they pass through narrow capillaries. These are the more obvious functions of a plasma membrane. In addition, the surface of the plasma membrane carries markers that allow cells to recognize one another, which is vital for tissue and organ formation during early development, and which later plays a role in the “self” versus “non-self” distinction of the immune response.

Among the most sophisticated functions of the plasma membrane is the ability to transmit signals by means of complex, integral proteins known as receptors. These proteins act both as receivers of extracellular inputs and as activators of intracellular processes. These membrane receptors provide extracellular attachment sites for effectors like hormones and growth factors, and they activate intracellular response cascades when their effectors are bound. Occasionally, receptors are hijacked by viruses (HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, is one example) that use them to gain entry into cells, and at times, the genes encoding receptors become mutated, causing the process of signal transduction to malfunction with disastrous consequences.

Fluid Mosaic Model

The existence of the plasma membrane was identified in the 1890s, and its chemical components were identified in 1915. The principal components identified at that time were lipids and proteins. The first widely accepted model of the plasma membrane’s structure was proposed in 1935 by Hugh Davson and James Danielli; it was based on the “railroad track” appearance of the plasma membrane in early electron micrographs. They theorized that the structure of the plasma membrane resembles a sandwich, with protein being analogous to the bread, and lipids being analogous to the filling. In the 1950s, advances in microscopy, notably transmission electron microscopy (TEM), allowed researchers to see that the core of the plasma membrane consisted of a double, rather than a single, layer. A new model that better explains both the microscopic observations and the function of that plasma membrane was proposed by S.J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson in 1972.

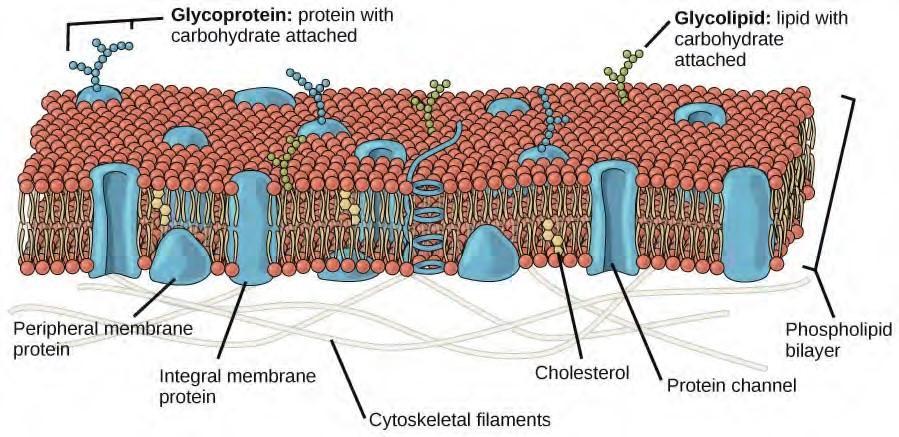

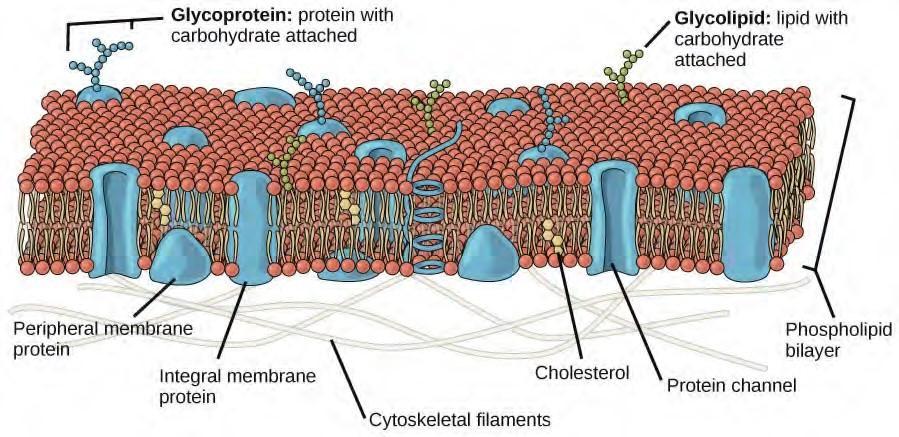

The explanation proposed by Singer and Nicolson is called the fluid mosaic model. The model has evolved somewhat over time, but it still best accounts for the structure and functions of the plasma membrane as we now understand them. The fluid mosaic model describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components—including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates—that gives the membrane a fluid character. Plasma membranes range from 5 to 10 nm in thickness. For comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm wide, or approximately 1,000 times wider than a plasma membrane. The membrane does look a bit like a sandwich (Figure 4.33).

Figure 4.33 The fluid mosaic model of the plasma membrane describes the plasma membrane as a fluid combination of phospholipids, cholesterol, and proteins. Carbohydrates attached to lipids (glycolipids) and to proteins (glycoproteins) extend from the outward-facing surface of the membrane.

The principal components of a plasma membrane are lipids (phospholipids and cholesterol), proteins, and carbohydrates attached to some of the lipids and some of the proteins. A phospholipid is a molecule consisting of glycerol, two fatty acids, and a phosphate-linked head group. Cholesterol, another lipid composed of four fused carbon rings, is found alongside the phospholipids in the core of the membrane. The proportions of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates in the plasma membrane vary with cell type, but for a typical human cell, protein accounts for about 50 percent of the composition by mass, lipids (of all types) account for about 40 percent of the composition by mass, with the remaining 10 percent of the composition by mass being carbohydrates. However, the concentration of proteins and lipids varies with different cell membranes. For example, myelin, an outgrowth of the membrane of specialized cells that insulates the axons of the peripheral nerves, contains only 18 percent protein and 76 percent lipid. The mitochondrial inner membrane contains 76 percent protein and only 24 percent lipid. The plasma membrane of human red blood cells is 30 percent lipid. Carbohydrates are present only on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane and are attached to proteins, forming glycoproteins, or attached to lipids, forming glycolipids.

Phospholipids

The main fabric of the membrane is composed of amphiphilic, phospholipid molecules. The hydrophilic or “water-loving” areas of these molecules (which look like a collection of balls in an artist’s rendition of the model) (Figure 4.33) are in contact with the aqueous fluid both inside and outside the cell. Hydrophobic, or water-hating molecules, tend to be non-polar. They interact with other non-polar molecules in chemical reactions, but generally do not interact with polar molecules. When placed in water, hydrophobic molecules tend to form a ball or cluster. The hydrophilic regions of the phospholipids tend to form hydrogen bonds with water and other polar molecules on both the exterior and interior of the cell. Thus, the membrane surfaces that face the interior and exterior of the cell are hydrophilic. In contrast, the interior of the cell membrane is hydrophobic and will not interact with water. Therefore, phospholipids form an excellent two-layer cell membrane that separates fluid within the cell from the fluid outside of the cell.

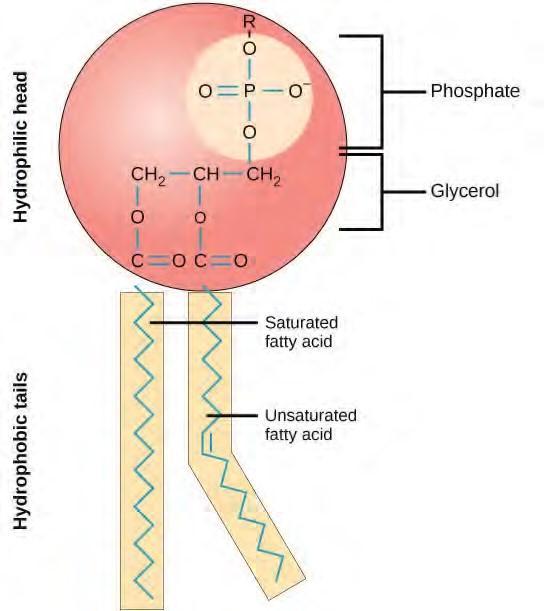

A phospholipid molecule (Figure 4.34) consists of a three-carbon glycerol backbone with two fatty acid molecules attached to carbons 1 and 2, and a phosphate-containing group attached to the third carbon. This arrangement gives the overall molecule an area described as its head (the phosphate-containing group), which has a polar character or negative charge, and an area called the tail (the fatty acids), which has no charge. The head can form hydrogen bonds, but the tail cannot. A molecule with this arrangement of a positively or negatively charged area and an uncharged, or non-polar, area is referred to as amphiphilic or “dual-loving.”

Figure 4.34 This phospholipid molecule is composed of a hydrophilic head and two hydrophobic tails. The hydrophilic head group consists of a phosphate-containing group attached to a glycerol molecule. The hydrophobic tails, each containing either a saturated or an unsaturated fatty acid, are long hydrocarbon chains.

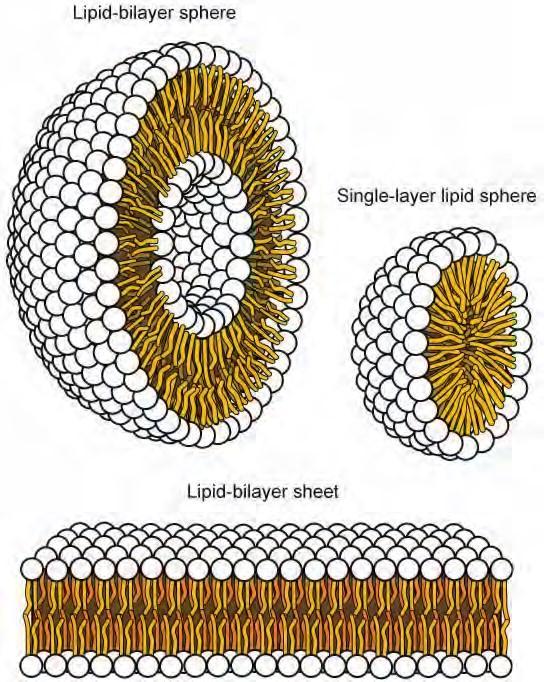

This characteristic is vital to the structure of a plasma membrane because, in water, phospholipids tend to become arranged with their hydrophobic tails facing each other and their hydrophilic heads facing out. In this way, they form a lipid bilayer—a barrier composed of a double layer of phospholipids that separates the water and other materials on one side of the barrier from the water and other materials on the other side. In fact, phospholipids heated in an aqueous solution tend to spontaneously form small spheres or droplets (called micelles or liposomes), with their hydrophilic heads forming the exterior and their hydrophobic tails on the inside (Figure 4.35).

Figure 4.34 In an aqueous solution, phospholipids tend to arrange themselves with their polar heads facing outward and their hydrophobic tails facing inward. (credit: modification of work by MarianaRuiz Villareal)

Proteins

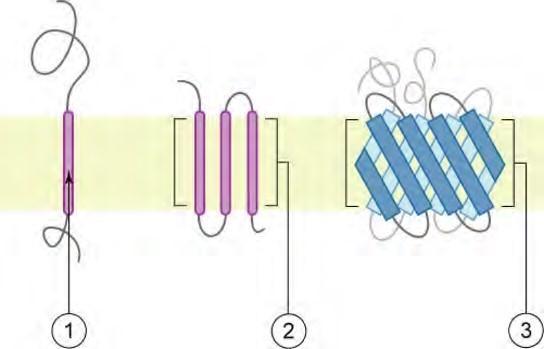

Proteins make up the second major component of plasma membranes. Integral proteins (some specialized types are called integrins) are, as their name suggests, integrated completely into the membrane structure, and their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interact with the hydrophobic region of the the phospholipid bilayer (Figure 4.33). Single-pass integral membrane proteins usually have a hydrophobic transmembrane segment that consists of 20–25 amino acids. Some span only part of the membrane—associating with a single layer—while others stretch from one side of the membrane to the other, and are exposed on either side. Some complex proteins are composed of up to 12 segments of a single protein, which are extensively folded and embedded in the membrane (Figure 4.36). This type of protein has a hydrophilic region or regions, and one or several mildly hydrophobic regions. This arrangement of regions of the protein tends to orient the protein alongside the phospholipids, with the hydrophobic region of the protein adjacent to the tails of the phospholipids and the hydrophilic region or regions of the protein protruding from the membrane and in contact with the cytosol or extracellular fluid.

Figure 4.36 Integral membranes proteins may have one or more alpha-helices that span the membrane (examples 1 and 2), or they may have beta-sheets that span the membrane (example 3). (credit: “Foobar”/Wikimedia Commons)

Peripheral proteins are found on the exterior and interior surfaces of membranes, attached either to integral proteins or to phospholipids. Peripheral proteins, along with integral proteins, may serve as enzymes, as structural attachments for the fibers of the cytoskeleton, or as part of the cell’s recognition sites. These are sometimes referred to as “cell-specific” proteins. The body recognizes its own proteins and attacks foreign proteins associated with invasive pathogens.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are the third major component of plasma membranes. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids) (Figure 4.33). These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2–60 monosaccharide units and can be either straight or branched. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other. These sites have unique patterns that allow the cell to be recognized, much the way that the facial features unique to each person allow him or her to be recognized. This recognition function is very important to cells, as it allows the immune system to differentiate between body cells (called “self”) and foreign cells or tissues (called “non-self”). Similar types of glycoproteins and glycolipids are found on the surfaces of viruses and may change frequently, preventing immune cells from recognizing and attacking them.

These carbohydrates on the exterior surface of the cell—the carbohydrate components of both glycoproteins and glycolipids—are collectively referred to as the glycocalyx (meaning “sugar coating”). The glycocalyx is highly hydrophilic and attracts large amounts of water to the surface of the cell. This aids in the interaction of the cell with its watery environment and in the cell’s ability to obtain substances dissolved in the water. As discussed above, the glycocalyx is also important for cell identification, self/ non-self determination, and embryonic development, and is used in cell-cell attachments to form tissues

Membrane Fluidity

The mosaic characteristic of the membrane, described in the fluid mosaic model, helps to illustrate its nature. The integral proteins and lipids exist in the membrane as separate but loosely attached molecules. These resemble the separate, multicolored tiles of a mosaic picture, and they float, moving somewhat with respect to one another. The membrane is not like a balloon, however, that can expand and contract; rather, it is fairly rigid and can burst if penetrated or if a cell takes in too much water. However, because of its mosaic nature, a very fine needle can easily penetrate a plasma membrane without causing it to burst, and the membrane will flow and self-seal when the needle is extracted.

Thus, if saturated fatty acids, with their straight tails, are compressed by decreasing temperatures, they press in on each other, making a dense and fairly rigid membrane. If unsaturated fatty acids are compressed, the “kinks” in their tails elbow adjacent phospholipid molecules away, maintaining some space between the phospholipid molecules. This “elbow room” helps to maintain fluidity in the membrane at temperatures at which membranes with saturated fatty acid tails in their phospholipids would “freeze” or solidify. The relative fluidity of the membrane is particularly important in a cold environment. A cold environment tends to compress membranes composed largely of saturated fatty acids, making them less fluid and more susceptible to rupturing. Many organisms (fish are one example) are capable of adapting to cold environments by changing the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in their membranes in response to the lowering of the temperature.

Visit this site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/biological_memb) to see animations of the fluidity and mosaic quality of membranes.

Animals have an additional membrane constituent that assists in maintaining fluidity. Cholesterol, which lies alongside the phospholipids in the membrane, tends to dampen the effects of temperature on the membrane. Thus, this lipid functions as a buffer, preventing lower temperatures from inhibiting fluidity and preventing increased temperatures from increasing fluidity too much. Thus, cholesterol extends, in both directions, the range of temperature in which the membrane is appropriately fluid and consequently functional. Cholesterol also serves other functions, such as organizing clusters of transmembrane proteins into lipid rafts.

The Components and Functions of the Plasma Membrane

|

Component |

Location |

|

Phospholipid |

Main fabric of the membrane |

|

Cholesterol |

Attached between phospholipids and between the two phospholipid layers |

|

Integral proteins (for example, integrins) |

Embedded within the phospholipid layer(s). May or may not penetrate through both layers |

|

Peripheral proteins |

On the inner or outer surface of the phospholipid bilayer; not embedded within the phospholipids |

|

Carbohydrates (components of glycoproteins and glycolipids) |

Generally attached to proteins on the outside membrane layer |

Table 4.2

4.8 | Passive Transport

Plasma membranes must allow certain substances to enter and leave a cell, and prevent some harmful materials from entering and some essential materials from leaving. In other words, plasma membranes are selectively permeable—they allow some substances to pass through, but not others. If they were to lose this selectivity, the cell would no longer be able to sustain itself, and it would be destroyed. Some cells require larger amounts of specific substances than do other cells; they must have a way of obtaining these materials from extracellular fluids. This may happen passively, as certain materials move back and forth, or the cell may have special mechanisms that facilitate transport. Some materials are so important to a cell that it spends some of its energy, hydrolyzing adenosine triphosphate (ATP), to obtain these materials. Red blood cells use some of their energy doing just that. All cells spend the majority of their energy to maintain an imbalance of sodium and potassium ions between the interior and exterior of the cell.

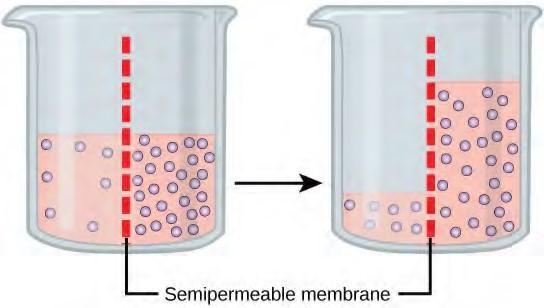

The most direct forms of membrane transport are passive. Passive transport is a naturally occurring phenomenon and does not require the cell to exert any of its energy to accomplish the movement. In passive transport, substances move from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. A physical space in which there is a range of concentrations of a single substance is said to have a concentration gradient.

Selective Permeability

Plasma membranes are asymmetric: the interior of the membrane is not identical to the exterior of the membrane. In fact, there is a considerable difference between the array of phospholipids and proteins between the two leaflets that form a membrane. On the interior of the membrane, some proteins serve to anchor the membrane to fibers of the cytoskeleton. There are peripheral proteins on the exterior of the membrane that bind elements of the extracellular matrix. Carbohydrates, attached to lipids or proteins, are also found on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane. These carbohydrate complexes help the cell bind substances that the cell needs in the extracellular fluid. This adds considerably to the selective nature of plasma membranes (Figure 4.38).

Figure 4.38 The exterior surface of the plasma membrane is not identical to the interior surface of the same membrane.

Polar substances present problems for the membrane. While some polar molecules connect easily with the outside of a cell, they cannot readily pass through the lipid core of the plasma membrane. Additionally, while small ions could easily slip through the spaces in the mosaic of the membrane, their charge prevents them from doing so. Ions such as sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride must have special means of penetrating plasma membranes. Simple sugars and amino acids also need help with transport across plasma membranes, achieved by various transmembrane proteins (channels).

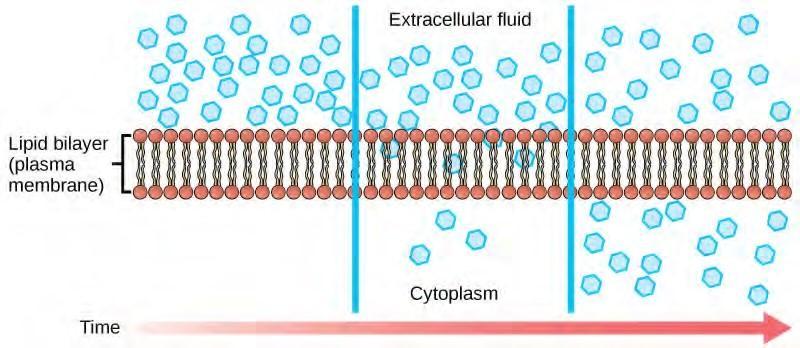

Diffusion

Diffusion is a passive process of transport. A single substance tends to move from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration until the concentration is equal across a space. You are familiar with diffusion of substances through the air. For example, think about someone opening a bottle of ammonia in a room filled with people. The ammonia gas is at its highest concentration in the bottle; its lowest concentration is at the edges of the room. The ammonia vapor will diffuse, or spread away, from the bottle, and gradually, more and more people will smell the ammonia as it spreads. Materials move within the cell’s cytosol by diffusion, and certain materials move through the plasma membrane by diffusion (Figure 4.39). Diffusion expends no energy. On the contrary, concentration gradients are a form of potential energy, dissipated as the gradient is eliminated.

Figure 4.39 Diffusion through a permeable membrane moves a substance from an area of high concentration (extracellular fluid, in this case) down its concentration gradient (into the cytoplasm). (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

Each separate substance in a medium, such as the extracellular fluid, has its own concentration gradient, independent of the concentration gradients of other materials. In addition, each substance will diffuse according to that gradient. Within a system, there will be different rates of diffusion of the different substances in the medium.

Factors That Affect Diffusion

Molecules move constantly in a random manner, at a rate that depends on their mass, their environment, and the amount of thermal energy they possess, which in turn is a function of temperature. This movement accounts for the diffusion of molecules through whatever medium in which they are localized. A substance will tend to move into any space available to it until it is evenly distributed throughout it. After a substance has diffused completely through a space, removing its concentration gradient, molecules will still move around in the space, but there will be no net movement of the number of molecules from one area to another. This lack of a concentration gradient in which there is no net movement of a substance is known as dynamic equilibrium. While diffusion will go forward in the presence of a concentration gradient of a substance, several factors affect the rate of diffusion.

- Extent of the concentration gradient: The greater the difference in concentration, the more rapid the diffusion. The closer the distribution of the material gets to equilibrium, the slower the rate of diffusion becomes.

- Mass of the molecules diffusing: Heavier molecules move more slowly; therefore, they diffuse more slowly. The reverse is true for lighter molecules.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase the energy and therefore the movement of the molecules, increasing the rate of diffusion. Lower temperatures decrease the energy of the molecules, thus decreasing the rate of diffusion.

- Solvent density: As the density of a solvent increases, the rate of diffusion decreases. The molecules slow down because they have a more difficult time getting through the denser medium. If the medium is less dense, diffusion increases. Because cells primarily use diffusion to move materials within the cytoplasm, any increase in the cytoplasm’s density will inhibit the movement of the materials. An example of this is a person experiencing dehydration. As the body’s cells lose water, the rate of diffusion decreases in the cytoplasm, and the cells’ functions deteriorate. Neurons tend to be very sensitive to this effect. Dehydration frequently leads to unconsciousness and possibly coma because of the decrease in diffusion rate within the cells.

- Solubility: As discussed earlier, nonpolar or lipid-soluble materials pass through plasma membranes more easily than polar materials, allowing a faster rate of diffusion.

- Surface area and thickness of the plasma membrane: Increased surface area increases the rate of diffusion, whereas a thicker membrane reduces it.

- Distance travelled: The greater the distance that a substance must travel, the slower the rate of diffusion. This places an upper limitation on cell size. A large, spherical cell will die because nutrients or waste cannot reach or leave the center of the cell, respectively. Therefore, cells must either be small in size, as in the case of many prokaryotes, or be flattened, as with many single celled eukaryotes.

A variation of diffusion is the process of filtration. In filtration, material moves according to its concentration gradient through a membrane; sometimes the rate of diffusion is enhanced by pressure, causing the substances to filter more rapidly. This occurs in the kidney, where blood pressure forces large amounts of water and accompanying dissolved substances, or solutes, out of the blood and into the renal tubules. The rate of diffusion in this instance is almost totally dependent on pressure. One of the effects of high blood pressure is the appearance of protein in the urine, which is “squeezed through” by the abnormally high pressure.

Facilitated transport

In facilitated transport, also called facilitated diffusion, materials diffuse across the plasma membrane with the help of membrane proteins. A concentration gradient exists that would allow these materials to diffuse into the cell without expending cellular energy. However, these materials are ions are polar molecules that are repelled by the hydrophobic parts of the cell membrane. Facilitated transport proteins shield these materials from the repulsive force of the membrane, allowing them to diffuse into the cell.

The material being transported is first attached to protein or glycoprotein receptors on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane. This allows the material that is needed by the cell to be removed from the extracellular fluid. The substances are then passed to specific integral proteins that facilitate their passage. Some of these integral proteins are collections of beta pleated sheets that form a pore or channel through the phospholipid bilayer. Others are carrier proteins which bind with the substance and aid its diffusion through the membrane.

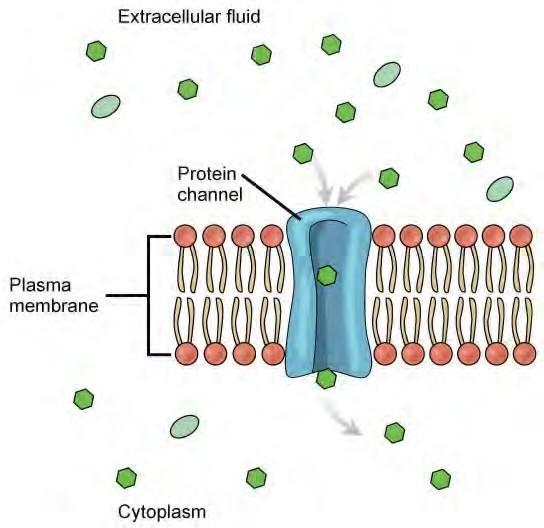

Channels

The integral proteins involved in facilitated transport are collectively referred to as transport proteins, and they function as either channels for the material or carriers. In both cases, they are transmembrane proteins. Channels are specific for the substance that is being transported. Channel proteins have hydrophilic domains exposed to the intracellular and extracellular fluids; they additionally have a hydrophilic channel through their core that provides a hydrated opening through the membrane layers (Figure 4.40). Passage through the channel allows polar compounds to avoid the nonpolar central layer of the plasma membrane that would otherwise slow or prevent their entry into the cell. Aquaporins are channel proteins that allow water to pass through the membrane at a very high rate.

Figure 4.40 Facilitated transport moves substances down their concentration gradients. They may cross the plasma membrane with the aid of channel proteins. (credit: modification of work by MarianaRuiz Villareal)

Channel proteins are either open at all times or they are “gated,” which controls the opening of the channel. The attachment of a particular ion to the channel protein may control the opening, or other mechanisms or substances may be involved. In some tissues, sodium and chloride ions pass freely through open channels, whereas in other tissues a gate must be opened to allow passage. An example of this occurs in the kidney, where both forms of channels are found in different parts of the renal tubules. Cells involved in the transmission of electrical impulses, such as nerve and muscle cells, have gated channels for sodium, potassium, and calcium in their membranes. Opening and closing of these channels changes the relative concentrations on opposing sides of the membrane of these ions, resulting in the facilitation of electrical transmission along membranes (in the case of nerve cells) or in muscle contraction (in the case of muscle cells).

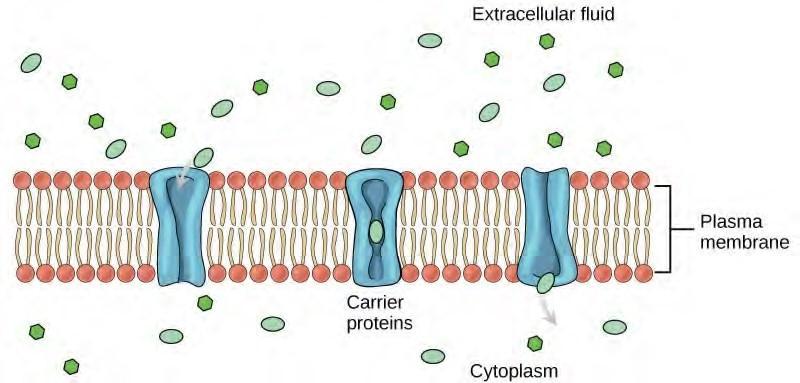

Carrier Proteins

Another type of protein embedded in the plasma membrane is a carrier protein. This aptly named protein binds a substance and, in doing so, triggers a change of its own shape, moving the bound molecule from the outside of the cell to its interior (Figure 4.41); depending on the gradient, the material may move in the opposite direction. Carrier proteins are typically specific for a single substance. This selectivity adds to the overall selectivity of the plasma membrane. The exact mechanism for the change of shape is poorly understood. Proteins can change shape when their hydrogen bonds are affected, but this may not fully explain this mechanism. Each carrier protein is specific to one substance, and there are a finite number of these proteins in any membrane. This can cause problems in transporting enough of the material for the cell to function properly. When all of the proteins are bound to their ligands, they are saturated and the rate of transport is at its maximum. Increasing the concentration gradient at this point will not result in an increased rate of transport.

Figure 4.41 Some substances are able to move down their concentration gradient across the plasma membrane with the aid of carrier proteins. Carrier proteins change shape as they move molecules across the membrane. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

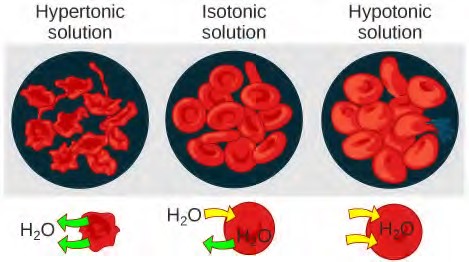

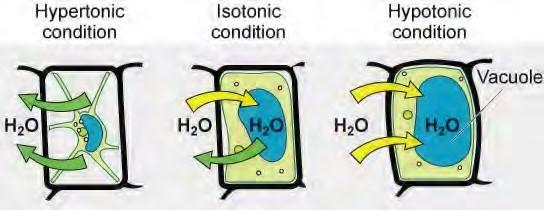

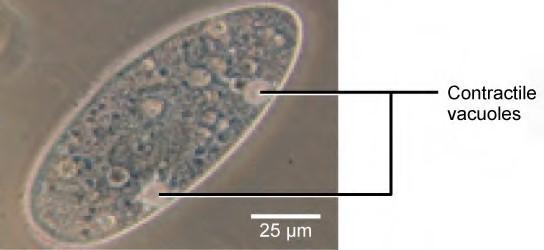

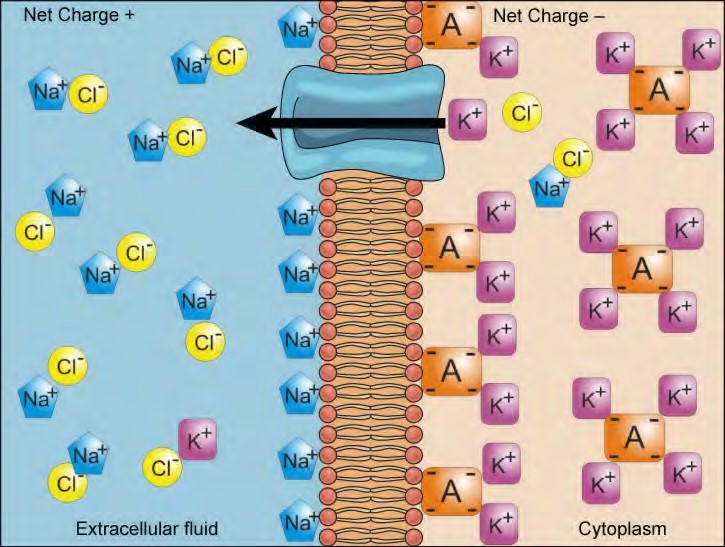

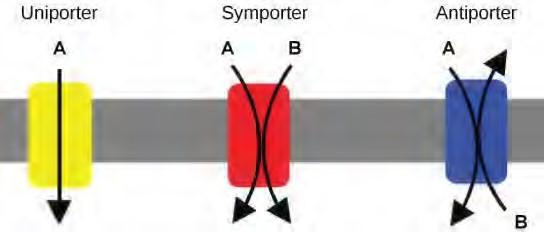

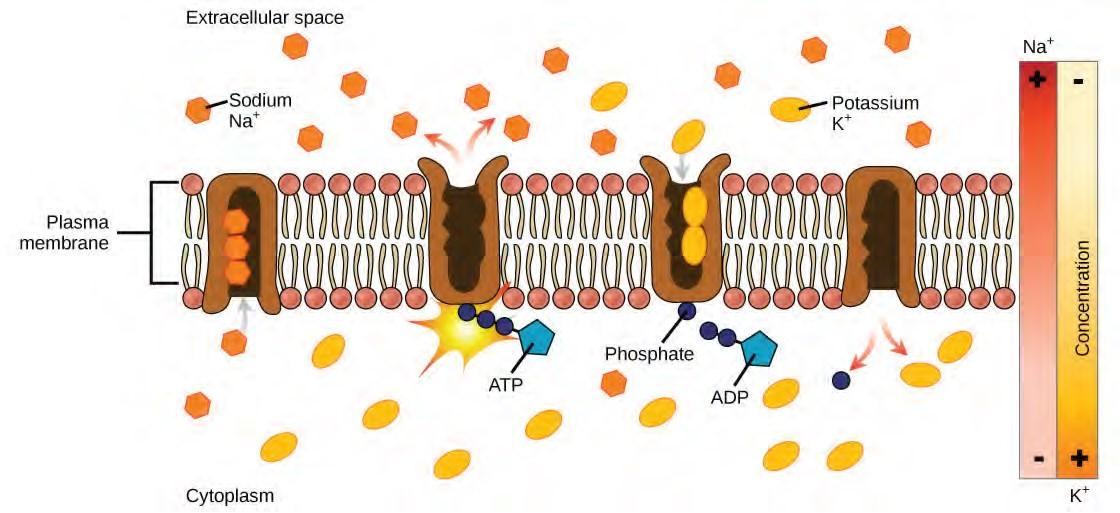

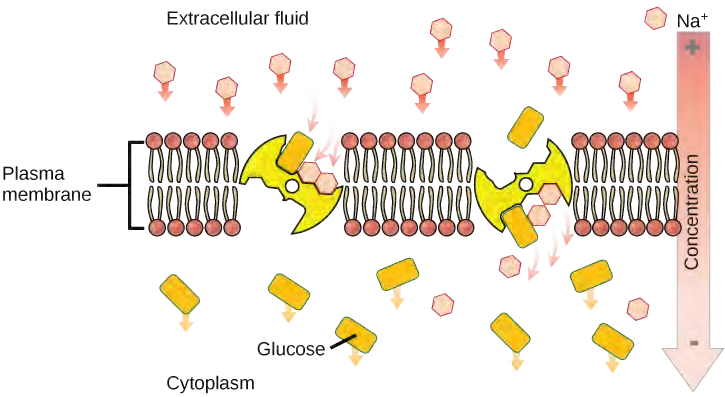

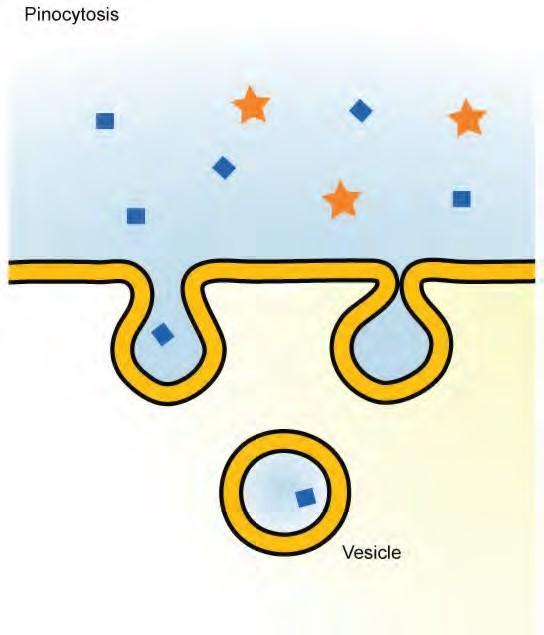

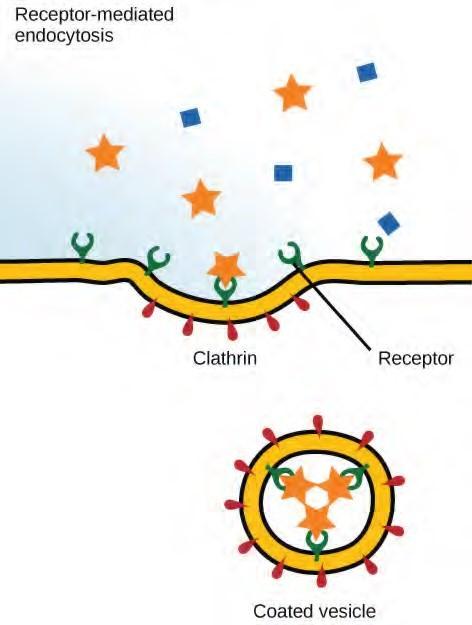

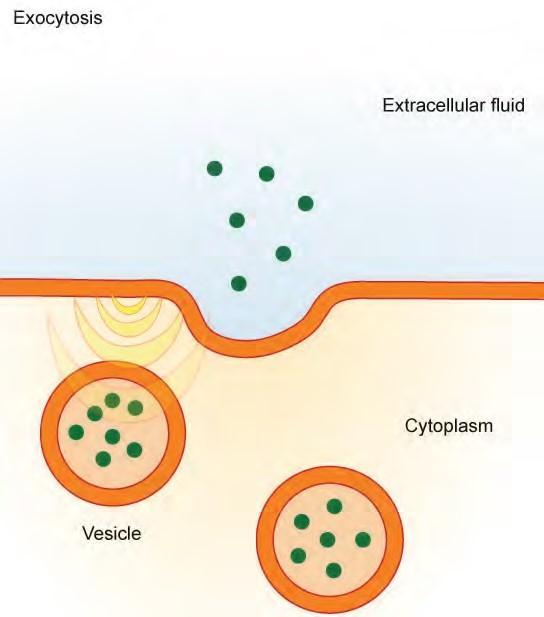

An example of this process occurs in the kidney. Glucose, water, salts, ions, and amino acids needed by the body are filtered in one part of the kidney. This filtrate, which includes glucose, is then reabsorbed in another part of the kidney. Because there are only a finite number of carrier proteins for glucose, if more glucose is present than the proteins can handle, the excess is not transported and it is excreted from the body in the urine. In a diabetic individual, this is described as “spilling glucose into the urine.” A different group of carrier proteins called glucose transport proteins, or GLUTs, are involved in transporting glucose and other hexose sugars through plasma membranes within the body.