7 Chapter 7: Mitosis and Meiosis

Chapter Outline

- 7.1 Cell Division

- 7.2 Cell Cycle

- 7.3 Control of the Cell Cycle

- 7.4 Cancer and the Cell Cycle

- 7.5 Prokaryotic Cell Division

- 7.6 The Process of Meiosis

- 7.7 Comparing Meiosis and Mitosis

- 7.8 Sexual Reproduction

Figure 7.1 A sea urchin begins life as a single cell that (a) divides to form two cells, visible by scanning electron microscopy. After four rounds of cell division, (b) there are 16 cells, as seen in this SEM image. After many rounds of cell division, the individual develops into a complex, multicellular organism, as seen in this (c) mature sea urchin. (credit a: modification of work by Evelyn Spiegel, Louisa Howard; credit b: modification of work by Evelyn Spiegel, Louisa Howard; credit c:modification of work by Marco Busdraghi; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Introduction

A human, as well as every sexually reproducing organism, begins life as a fertilized egg (embryo) or zygote. Trillions of cell divisions subsequently occur in a controlled manner to produce a complex, multicellular human. In other words, that original single cell is the ancestor of every other cell in the body. Once a being is fully grown, cell reproduction is still necessary to repair or regenerate tissues. For example, new blood and skin cells are constantly being produced. All multicellular organisms use cell division for growth and the maintenance and repair of cells and tissues. Cell division is tightly regulated, and the occasional failure of regulation can have life-threatening consequences. Single-celled organisms use cell division as their method of reproduction.

The ability to reproduce in kind is a basic characteristic of all living things. In kind means that the offspring of any organism closely resemble their parent or parents. Hippopotamuses give birth to hippopotamus calves, Joshua trees produce seeds from which Joshua tree seedlings emerge, and adult flamingos lay eggs that hatch into flamingo chicks. In kind does not generally mean exactly the same. Whereas many unicellular organisms and a few multicellular organisms can produce genetically identical clones of themselves through cell division, many single-celled organisms and most multicellular organisms reproduce regularly using another method. Sexual reproduction is the production by parents of two haploid cells and the fusion of two haploid cells to form a single, unique diploid cell. In most plants and animals, through tens of rounds of mitotic cell division, this diploid cell will develop into an adult organism. Haploid cells that are part of the sexual reproductive cycle are produced by a type of cell division called meiosis. Sexual reproduction, specifically meiosis and fertilization, introduces variation into offspring that may account for the evolutionary success of sexual reproduction. The vast majority of eukaryotic organisms, both multicellular and unicellular, can or must employ some form of meiosis and fertilization to reproduce.

Learning Objectives

You will be able to describe mitosis and meiosis as the process to make cells :

- How mitosis transfers genetic material to offspring

- Recognize the steps in mitosis

- Understand the cell cycle

- Cell differentiation creates tissues

- Unregulated cell division can lead to cancer

- How meiosis allows for sexual reproduction

- Where and how gametes are generated

- Describe the difference between haploid and diploid

- Describe how mutations happen and their role in disease and evolution

7.1 | Cell Division

The continuity of life from one cell to another has its foundation in the reproduction of cells by way of the cell cycle. The cell cycle is an orderly sequence of events that describes the stages of a cell’s life from the division of a single parent cell to the production of two new daughter cells. The mechanisms involved in the cell cycle are highly regulated.

Genomic DNA

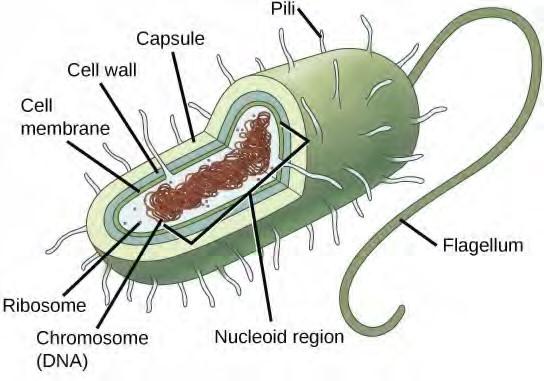

Before discussing the steps a cell must undertake to replicate, a deeper understanding of the structure and function of a cell’s genetic information is necessary. A cell’s DNA, packaged as a double-stranded DNA molecule, is called its genome. In prokaryotes, the genome is composed of a single, double stranded DNA molecule in the form of a loop or circle (Figure 7.2). The region in the cell containing this genetic material is called a nucleoid. Some prokaryotes also have smaller loops of DNA called plasmids that are not essential for normal growth. Bacteria can exchange these plasmids with other bacteria, sometimes receiving beneficial new genes that the recipient can add to their chromosomal DNA. Antibiotic resistance is one trait that often spreads through a bacterial colony through plasmid exchange.

Figure 7.2 Prokaryotes, including bacteria and archaea, have a single, circular chromosome located in a central region called the nucleoid.

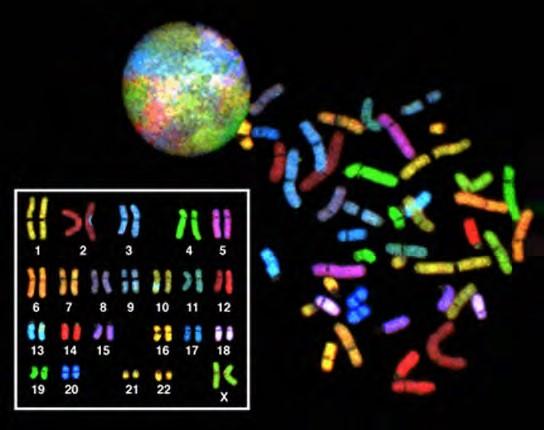

In eukaryotes, the genome consists of several double-stranded linear DNA molecules (Figure 7.3). Each species of eukaryotes has a characteristic number of chromosomes in the nuclei of its cells. Human body cells have 46 chromosomes, while human gametes (sperm or eggs) have 23 chromosomes each. A typical body cell, or somatic cell, contains two matched sets of chromosomes, a configuration known as diploid. The letter n is used to represent a single set of chromosomes; therefore, a diploid organism is designated 2n. Human cells that contain one set of chromosomes are called gametes, or sex cells; these are eggs and sperm, and are designated 1n, or haploid.

Figure 7.3 There are 23 pairs of homologous chromosomes in a female human somatic cell. The condensed chromosomes are viewed within the nucleus (top), removed from a cell in mitosis and spread out on a slide (right), and artificially arranged according to length (left); an arrangement like this is called a karyotype. In this image, the chromosomes were exposed to fluorescent stains for differentiation of the different chromosomes. A method of staining called “chromosome painting” employs fluorescent dyes that highlight chromosomes in different colors. (credit: National Human Genome Project/NIH)

Each copy of a homologous pair of chromosomes originates from a different parent; therefore, the genes themselves are not identical. The variation of individuals within a species is due to the specific combination of the genes inherited from both parents. Even a slightly altered sequence of nucleotides within a gene can result in an alternative trait. For example, there are three possible gene sequences on the human chromosome that code for blood type: sequence A, sequence B, and sequence O. Because all diploid human cells have two copies of the chromosome that determines blood type, the blood type (the trait) is determined by which two versions of the marker gene are inherited. It is possible to have two copies of the same gene sequence on both homologous chromosomes, with one on each (for example,AA, BB, or OO), or two different sequences, such as AB.Minor variations of traits, such as blood type, eye color, and handedness, contribute to the natural variation found within a species. However, if the entire DNA sequence from any pair of human homologous chromosomes is compared, the difference is less than one percent. The sex chromosomes, X and Y, are the single exception to the rule of homologous chromosome uniformity: Other than a small amount of homology that is necessary to accurately produce gametes, the genes found on the X and Y chromosomes are different.

Eukaryotic Chromosomal Structure and Compaction

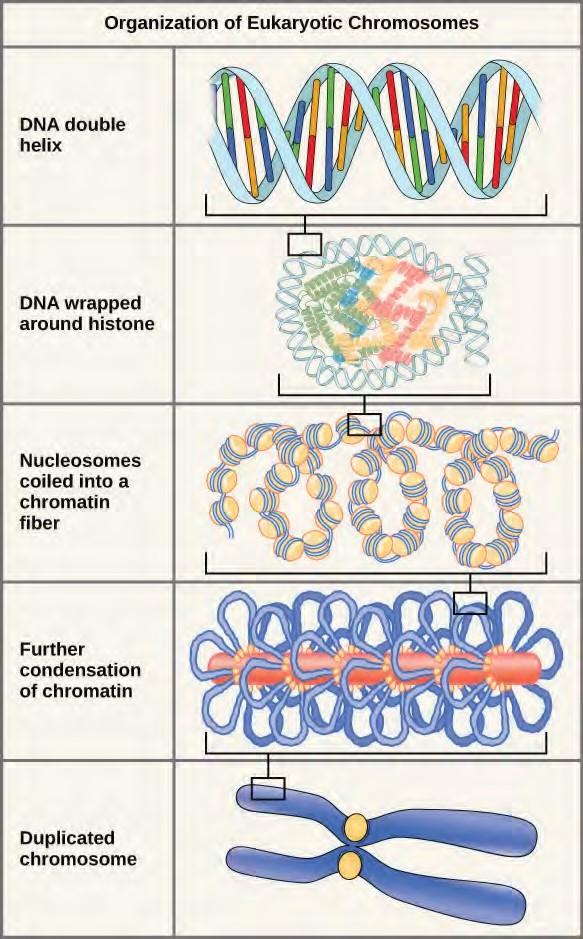

If the DNA from all 46 chromosomes in a human cell nucleus was laid out end to end, it would measure approximately two meters; however, its diameter would be only 2 nm. Considering that the size of a typical human cell is about 10 µm (100,000 cells lined up to equal one meter), DNA must be tightly packaged to fit in the cell’s nucleus. At the same time, it must also be readily accessible for the genes to be expressed. During some stages of the cell cycle, the long strands of DNA are condensed into compact chromosomes. There are a number of ways that chromosomes are compacted.

In the first level of compaction, short stretches of the DNA double helix wrap around a core of eight histone proteins at regular intervals along the entire length of the chromosome (Figure 7.4). The DNA histone complex is called chromatin. The beadlike, histone DNA complex is called a nucleosome, and DNA connecting the nucleosomes is called linker DNA. A DNA molecule in this form is about seven times shorter than the double helix without the histones, and the beads are about 10 nm in diameter, in contrast with the 2-nm diameter of a DNA double helix. The next level of compaction occurs as the nucleosomes and the linker DNA between them are coiled into a 30-nm chromatin fiber. This coiling further shortens the chromosome so that it is now about 50 times shorter than the extended form. In the third level of packing, a variety of fibrous proteins is used to pack the chromatin. These fibrous proteins also ensure that each chromosome in a non-dividing cell occupies a particular area of the nucleus that does not overlap with that of any other chromosome (see the top image in Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.4 Double-stranded DNA wraps around histone proteins to form nucleosomes that have the appearance of “beads on a string.” The nucleosomes are coiled into a 30-nm chromatin fiber. When a cell undergoes mitosis, the chromosomes condense even further.DNA replicates in the S phase of interphase. After replication, the chromosomes are composed of two linked sister chromatids. When fully compact, the pairs of identically packed chromosomes are bound to each other by cohesin proteins. The connection between the sister chromatids is closest in a region called the centromere. The conjoined sister chromatids, with a diameter of about 1 µm, are visible under a light microscope. The centromeric region is highly condensed and thus will appear as a constricted area.

This animation (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Packaged_DNA) illustrates the different levels of chromosome packing.

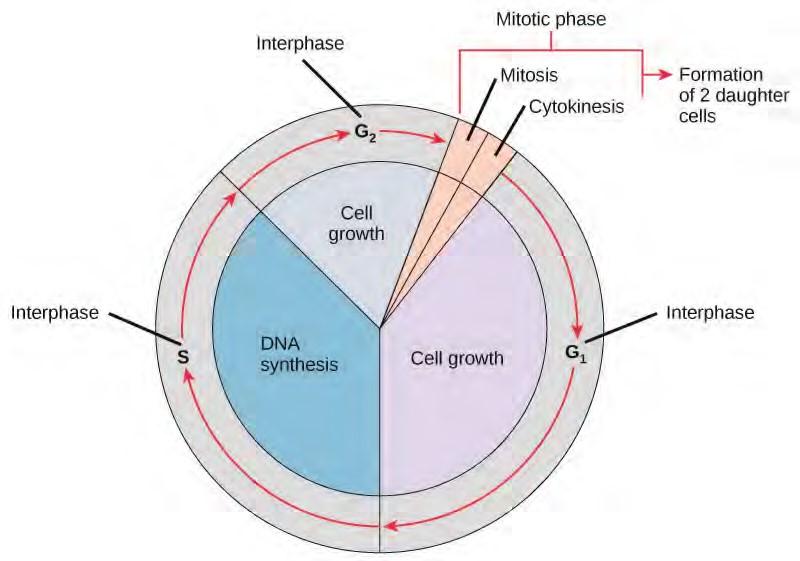

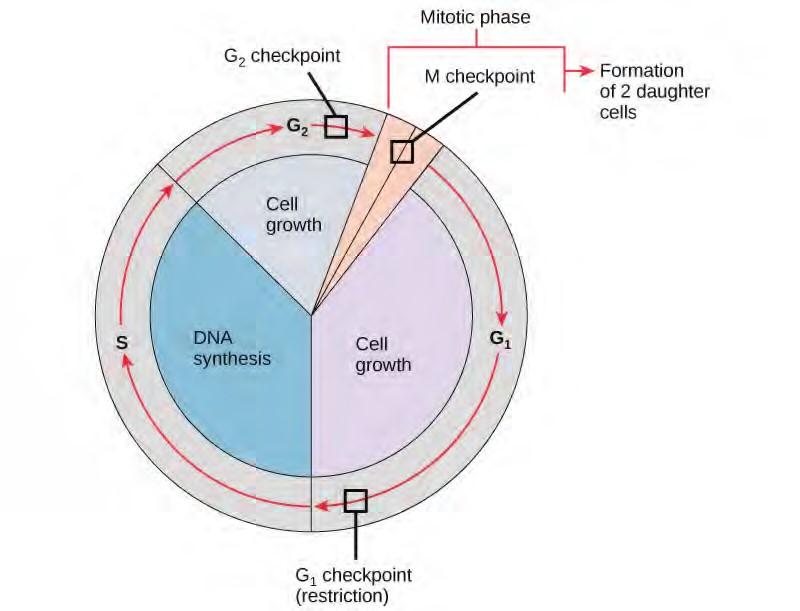

7.2 | The Cell Cycle

The cell cycle is an ordered series of events involving cell growth and cell division that produces two new daughter cells. Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of precisely timed and carefully regulated stages of growth, DNA replication, and division that produces two identical (clone) cells. The cell cycle has two major phases: interphase and the mitotic phase (Figure 7.5). During interphase, the cell grows and DNA is replicated. During the mitotic phase, the replicated DNA and cytoplasmic contents are separated, and the cell divides.

Figure 7.5 The cell cycle consists of interphase and the mitotic phase. During interphase, the cell grows and the nuclear DNA is duplicated. Interphase is followed by the mitotic phase. During the mitotic phase, the duplicated chromosomes are segregated and distributed into daughter nuclei. The cytoplasm is usually divided as well, resulting in two daughter cells.

Interphase

During interphase, the cell undergoes normal growth processes while also preparing for cell division. In order for a cell to move from interphase into the mitotic phase, many internal and external conditions must be met. The three stages of interphase are called G1, S, and G2.

G1 Phase (First Gap)

The first stage of interphase is called the G1 phase (first gap) because, from a microscopic aspect, little change is visible. However, during the G1 stage, the cell is quite active at the biochemical level. The cell is accumulating the building blocks of chromosomal DNA and the associated proteins as well as accumulating sufficient energy reserves to complete the task of replicating each chromosome in the nucleus.

S Phase (Synthesis of DNA)

Throughout interphase, nuclear DNA remains in a semi-condensed chromatin configuration. In the S phase, DNA replication can proceed through the mechanisms that result in the formation of identical pairs of DNA molecules—sister chromatids—that are firmly attached to the centromeric region. The centrosome is duplicated during the S phase. The two centrosomes will give rise to the mitotic spindle, the apparatus that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis. At the center of each animal cell, the centrosomes of animal cells are associated with a pair of rod-like objects, the centrioles, which are at right angles to each other. Centrioles help organize cell division. Centrioles are not present in the centrosomes of other eukaryotic species, such as plants and most fungi.

G2 Phase (Second Gap)

In the G2 phase, the cell replenishes its energy stores and synthesizes proteins necessary for chromosome manipulation. Some cell organelles are duplicated, and the cytoskeleton is dismantled to provide resources for the mitotic phase. There may be additional cell growth during G2. The final preparations for the mitotic phase must be completed before the cell is able to enter the first stage of mitosis.

The Mitotic Phase

The mitotic phase is a multistep process during which the duplicated chromosomes are aligned, separated, and move into two new, identical daughter cells. The first portion of the mitotic phase is called karyokinesis, or nuclear division. The second portion of the mitotic phase, called cytokinesis, is the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into the two daughter cells.

Revisit the stages of mitosis at this site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Cell_cycle_mito) .

Karyokinesis (Mitosis)

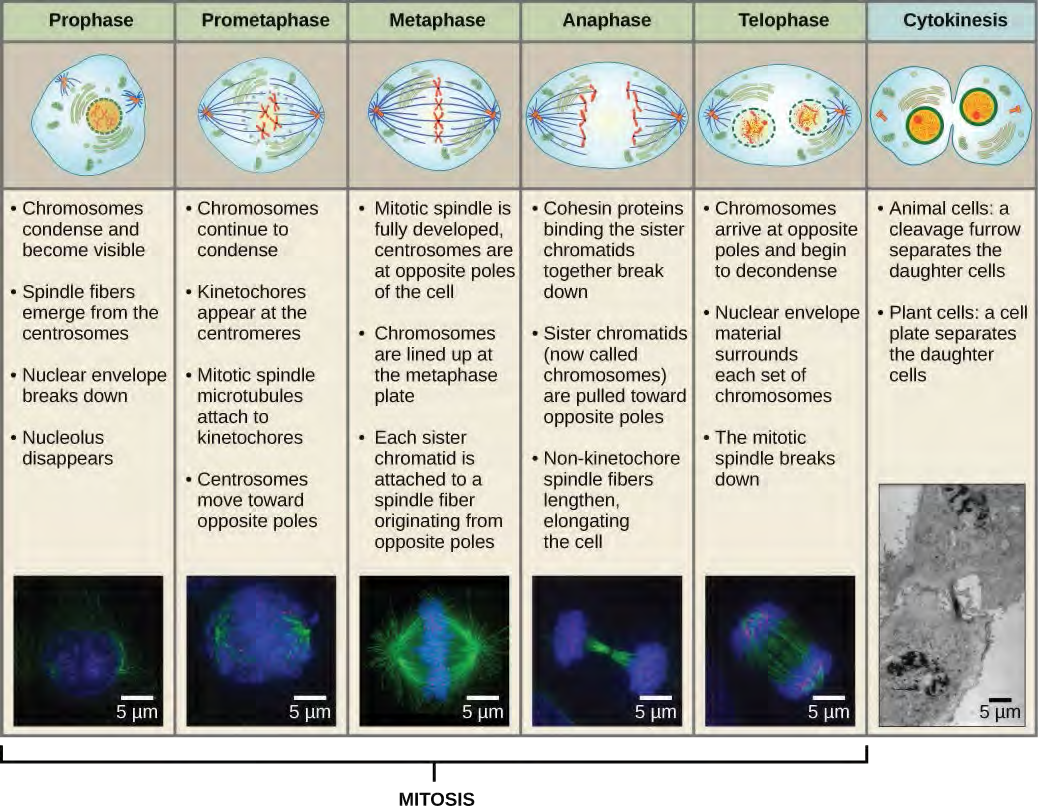

Karyokinesis, also known as mitosis, is divided into a series of phases—prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—that result in the division of the cell nucleus (Figure 10.6). Karyokinesis is also called mitosis.

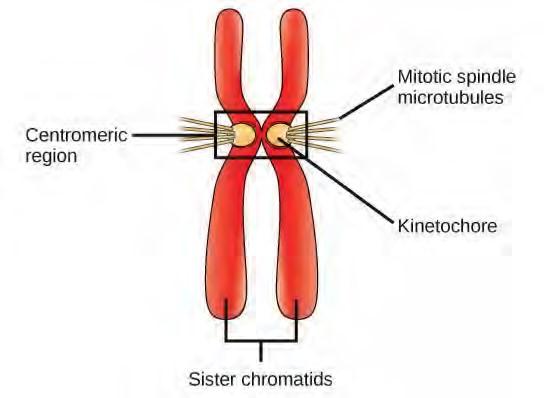

During prophase, the “first phase,” the nuclear envelope starts to dissociate into small vesicles, and the membranous organelles (such as the Golgi complex or Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum), fragment and disperse toward the periphery of the cell. The nucleolus disappears (disperses). The centrosomes begin to move to opposite poles of the cell. Microtubules that will form the mitotic spindle extend between the centrosomes, pushing them farther apart as the microtubule fibers lengthen. The sister chromatids begin to coil more tightly with the aid of condensin proteins and become visible under a light microscope.During prometaphase, the “first change phase,” many processes that were begun in prophase continue to advance. The remnants of the nuclear envelope fragment. The mitotic spindle continues to develop as more microtubules assemble and stretch across the length of the former nuclear area. Chromosomes become more condensed and discrete. Each sister chromatid develops a protein structure called a kinetochore in the centromeric region (Figure 7.7). The proteins of the kinetochore attract and bind mitotic spindle microtubules. As the spindle microtubules extend from the centrosomes, some of these microtubules come into contact with and firmly bind to the kinetochores. Once a mitotic fiber attaches to a chromosome, the chromosome will be oriented until the kinetochores of sister chromatids face the opposite poles. Eventually, all the sister chromatids will be attached via their kinetochores to microtubules from opposing poles. Spindle microtubules that do not engage the chromosomes are called polar microtubules. These microtubules overlap each other midway between the two poles and contribute to cell elongation. Astral microtubules are located near the poles, aid in spindle orientation, and are required for the regulation of mitosis.

Figure 7.7 During prometaphase, mitotic spindle microtubules from opposite poles attach to each sister chromatid at the kinetochore. In anaphase, the connection between the sister chromatids breaks down, and the microtubules pull the chromosomes toward opposite poles.

During telophase, the “distance phase,” the chromosomes reach the opposite poles and begin to decondense (unravel), relaxing into a chromatin configuration. The mitotic spindles are depolymerized into tubulin monomers that will be used to assemble cytoskeletal components for each daughter cell. Nuclear envelopes form around the chromosomes, and nucleosomes appear within the nuclear area.

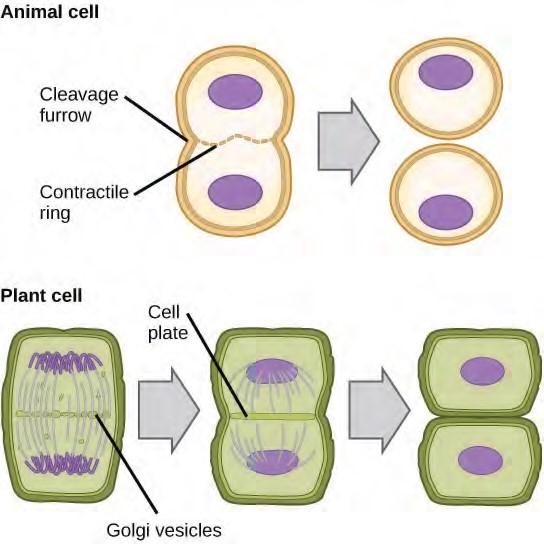

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis, or “cell motion,” is the second main stage of the mitotic phase during which cell division is completed via the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells. Division is not complete until the cell components have been apportioned and completely separated into the two daughter cells. Although the stages of mitosis are similar for most eukaryotes, the process of cytokinesis is quite different for eukaryotes that have cell walls, such as plant cells.

In plant cells, a new cell wall must form between the daughter cells. During interphase, the Golgi apparatus accumulates enzymes, structural proteins, and glucose molecules prior to breaking into vesicles and dispersing throughout the dividing cell. During telophase, these Golgi vesicles are transported on microtubules to form a phragmoplast (a vesicular structure) at the metaphase plate. There, the vesicles fuse and coalesce from the center toward the cell walls; this structure is called a cell plate. As more vesicles fuse, the cell plate enlarges until it merges with the cell walls at the periphery of the cell. Enzymes use the glucose that has accumulated between the membrane layers to build a new cell wall. The Golgi membranes become parts of the plasma membrane on either side of the new cell wall

(Figure 7.8).

Figure 7.8 During cytokinesis in animal cells, a ring of actin filaments forms at the metaphase plate. The ring contracts, forming a cleavage furrow, which divides the cell in two. In plant cells, Golgi vesicles coalesce at the former metaphase plate, forming a phragmoplast. A cell plate formed by the fusion of the vesicles of the phragmoplast grows from the center toward the cell walls, and the membranes of the vesicles fuse to form a plasma membrane that divides the cell in two.

G0 Phase

Not all cells adhere to the classic cell cycle pattern in which a newly formed daughter cell immediately enters the preparatory phases of interphase, closely followed by the mitotic phase. Cells in G0 phase are not actively preparing to divide. The cell is in a quiescent (inactive) stage that occurs when cells exit the cell cycle. Some cells enter G0 temporarily until an external signal triggers the onset of G1. Other cells that never or rarely divide, such as mature cardiac muscle and nerve cells, remain in G0 permanently.

7.3 | Control of the Cell Cycle

The length of the cell cycle is highly variable, even within the cells of a single organism. In humans, the frequency of cell turnover ranges from a few hours in early embryonic development, to an average of two to five days for epithelial cells, and to an entire human lifetime spent in G0 by specialized cells, such as cortical neurons or cardiac muscle cells. There is also variation in the time that a cell spends in each phase of the cell cycle. When fast-dividing mammalian cells are grown in culture (outside the body under optimal growing conditions), the length of the cycle is about 24 hours. In rapidly dividing human cells with a 24-hour cell cycle, the G1 phase lasts approximately nine hours, the S phase lasts 10 hours, the G2 phase lasts about four and one-half hours, and the M phase lasts approximately one-half hour. In early embryos of fruit flies, the cell cycle is completed in about eight minutes. The timing of events in the cell cycle is controlled by mechanisms that are both internal and external to the cell.

Regulation of the Cell Cycle by External Events

Both the initiation and inhibition of cell division are triggered by events external to the cell when it is about to begin the replication process. An event may be as simple as the death of a nearby cell or as sweeping as the release of growth-promoting hormones, such as human growth hormone (HGH). A lack of HGH can inhibit cell division, resulting in dwarfism, whereas too much HGH can result in gigantism. Crowding of cells can also inhibit cell division. Another factor that can initiate cell division is the size of the cell; as a cell grows, it becomes inefficient due to its decreasing surface-to-volume ratio. The solution to this problem is to divide.

Whatever the source of the message, the cell receives the signal, and a series of events within the cell allows it to proceed into interphase. Moving forward from this initiation point, every parameter required during each cell cycle phase must be met or the cycle cannot progress.

Regulation at Internal Checkpoints

It is essential that the daughter cells produced be exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes lead to mutations that may be passed forward to every new cell produced from an abnormal cell. To prevent a compromised cell from continuing to divide, there are internal control mechanisms that operate at three main cell cycle checkpoints. A checkpoint is one of several points in the eukaryotic cell cycle at which the progression of a cell to the next stage in the cycle can be halted until conditions are favorable. These checkpoints occur near the end of G1, at the G2/M transition, and during metaphase (Figure 7.10).

Figure 7.10 The cell cycle is controlled at three checkpoints. The integrity of the DNA is assessed at the G1 checkpoint. Proper chromosome duplication is assessed at the G2 checkpoint. Attachment of each kinetochore to a spindle fiber is assessed at the M checkpoint.

The G1 Checkpoint

The G1 checkpoint determines whether all conditions are favorable for cell division to proceed. The G1 checkpoint, also called the restriction point (in yeast), is a point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell division process. External influences, such as growth factors, play a large role in carrying the cell past the G1 checkpoint. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check for genomic DNA damage at the G1 checkpoint. A cell that does not meet all the requirements will not be allowed to progress into the S phase. The cell can halt the cycle and attempt to remedy the problematic condition, or the cell can advance into G0 and await further signals when conditions improve.

The G2 Checkpoint

The G2 checkpoint bars entry into the mitotic phase if certain conditions are not met. As at the G1 checkpoint, cell size and protein reserves are assessed. However, the most important role of the G2 checkpoint is to ensure that all of the chromosomes have been replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged. If the checkpoint mechanisms detect problems with the DNA, the cell cycle is halted, and the cell attempts to either complete DNA replication or repair the damaged DNA.

The M Checkpoint

The M checkpoint occurs near the end of the metaphase stage of karyokinesis. The M checkpoint is also known as the spindle checkpoint, because it determines whether all the sister chromatids are correctly attached to the spindle microtubules. Because the separation of the sister chromatids during anaphase is an irreversible step, the cycle will not proceed until the kinetochores of each pair of sister chromatids are firmly anchored to at least two spindle fibers arising from opposite poles of the cell.

Watch what occurs at the G1, G2, and M check points by visiting this website(http://openstaxcollege.org/l/cell_checkpnts) to see an animation of the cell cycle.

Regulator Molecules of the Cell Cycle

In addition to the internally controlled checkpoints, there are two groups of intracellular molecules that regulate the cell cycle. These regulatory molecules either promote progress of the cell to the next phase (positive regulation) or halt the cycle (negative regulation). Regulator molecules may act individually, or they can influence the activity or production of other regulatory proteins. Therefore, the failure of a single regulator may have almost no effect on the cell cycle, especially if more than one mechanism controls the same event. Conversely, the effect of a deficient or non-functioning regulator can be wide ranging and possibly fatal to the cell if multiple processes are affected.

Positive Regulation of the Cell Cycle

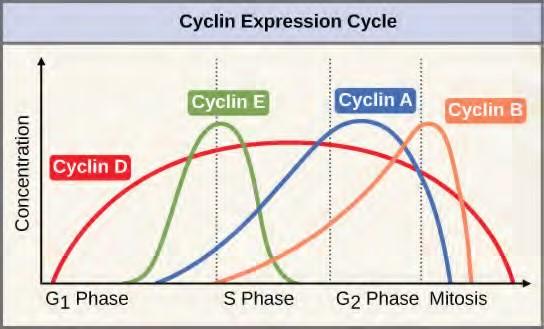

Two groups of proteins, called cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), are responsible for the progress of the cell through the various checkpoints. The levels of the four cyclin proteins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle in a predictable pattern (Figure 10.11). Increases in the concentration of cyclin proteins are triggered by both external and internal signals. After the cell moves to the next stage of the cell cycle, the cyclins that were active in the previous stage are degraded.

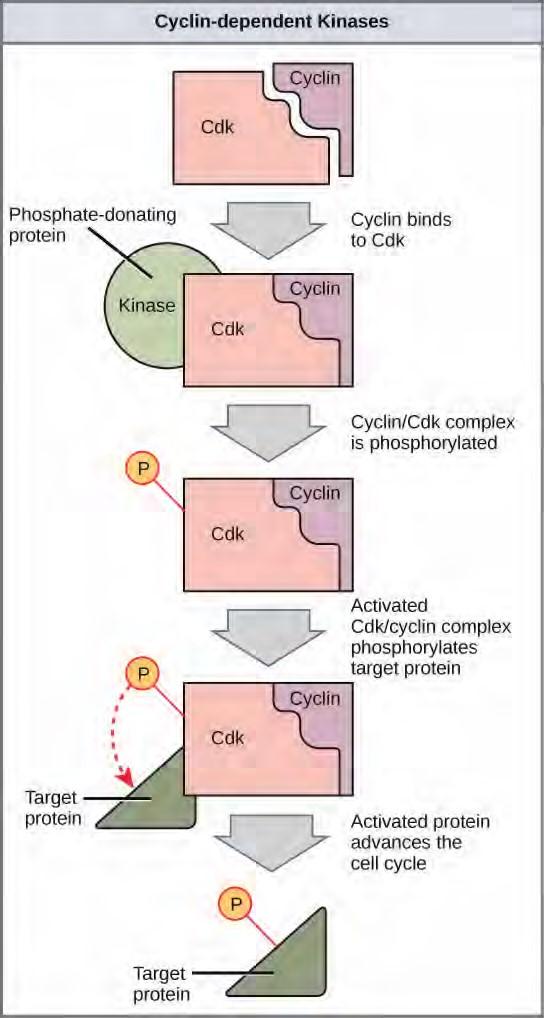

Figure 7.11 The concentrations of cyclin proteins change throughout the cell cycle. There is a direct correlation between cyclin accumulation and the three major cell cycle checkpoints. Also note the sharp decline of cyclin levels following each checkpoint (the transition between phases of the cell cycle), as cyclin is degraded by cytoplasmic enzymes. (credit: modification of work by “WikiMiMa”/Wikimedia Commons)Cyclins regulate the cell cycle only when they are tightly bound to Cdks. To be fully active, the Cdk/cyclin complex must also be phosphorylated in specific locations. Like all kinases, Cdks are enzymes (kinases) that phosphorylate other proteins. Phosphorylation activates the protein by changing its shape. The proteins phosphorylated by Cdks are involved in advancing the cell to the next phase. (Figure 7.12). The levels of Cdk proteins are relatively stable throughout the cell cycle; however, the concentrations of cyclin fluctuate and determine when Cdk/cyclin complexes form. The different cyclins and Cdks bind at specific points in the cell cycle and thus regulate different checkpoints.

Figure 7.12 Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) are protein kinases that, when fully activated, can phosphorylate and thus activate other proteins that advance the cell cycle past a checkpoint. To become fully activated, a Cdk must bind to a cyclin protein and then be phosphorylated by another kinase.

Although the cyclins are the main regulatory molecules that determine the forward momentum of the cell cycle, there are several other mechanisms that fine-tune the progress of the cycle with negative, rather than positive, effects. These mechanisms essentially block the progression of the cell cycle until problematic conditions are resolved. Molecules that prevent the full activation of Cdks are called Cdk inhibitors. Many of these inhibitor molecules directly or indirectly monitor a particular cell cycle event. The block placed on Cdks by inhibitor molecules will not be removed until the specific event that the inhibitor monitors is completed.

Negative Regulation of the Cell Cycle

The second group of cell cycle regulatory molecules are negative regulators. Negative regulators halt the cell cycle. Remember that in positive regulation, active molecules cause the cycle to progress.

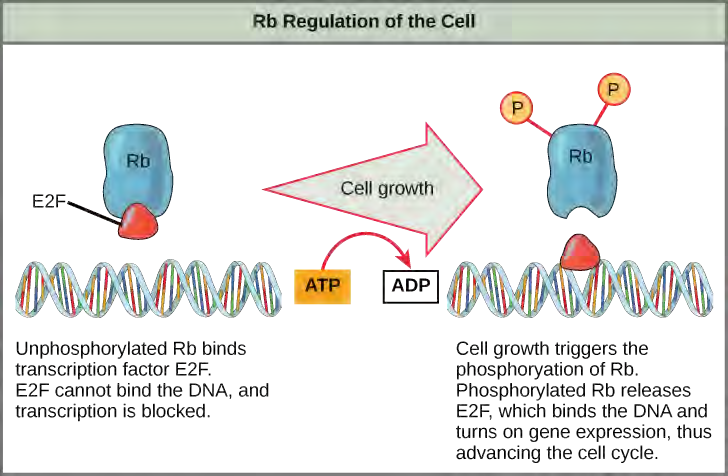

Rb exerts its regulatory influence on other positive regulator proteins. Chiefly, Rb monitors cell size. In the active, dephosphorylated state, Rb binds to proteins called transcription factors, most commonly, E2F (Figure 7.13). Transcription factors “turn on” specific genes, allowing the production of proteins encoded by that gene. When Rb is bound to E2F, production of proteins necessary for the G1/S transition is blocked. As the cell increases in size, Rb is slowly phosphorylated until it becomes inactivated. Rb releases E2F, which can now turn on the gene that produces the transition protein, and this particular block is removed. For the cell to move past each of the checkpoints, all positive regulators must be “turned on,” and all negative regulators must be “turned off.”

7.4 | Cancer and the Cell Cycle

Cancer comprises many different diseases caused by a common mechanism: uncontrolled cell growth. Despite the redundancy and overlapping levels of cell cycle control, errors do occur. One of the critical processes monitored by the cell cycle checkpoint surveillance mechanism is the proper replication of DNA during the S phase. Even when all of the cell cycle controls are fully functional, a small percentage of replication errors (mutations) will be passed on to the daughter cells. If changes to the DNA nucleotide sequence occur within a coding portion of a gene and are not corrected, a gene mutation results. All cancers start when a gene mutation gives rise to a faulty protein that plays a key role in cell reproduction. The change in the cell that results from the malformed protein may be minor: perhaps a slight delay in the binding of Cdk to cyclin or an Rb protein that detaches from its target DNA while still phosphorylated. Even minor mistakes, however, may allow subsequent mistakes to occur more readily. Over and over, small uncorrected errors are passed from the parent cell to the daughter cells and amplified as each generation produces more non-functional proteins from uncorrected DNA damage. Eventually, the pace of the cell cycle speeds up as the effectiveness of the control and repair mechanisms decreases. Uncontrolled growth of the mutated cells outpaces the growth of normal cells in the area, and a tumor (“-oma”) can result.

Proto-oncogenes

The genes that code for the positive cell cycle regulators are called proto-oncogenes. Proto-oncogenes are normal genes that, when mutated in certain ways, become oncogenes, genes that cause a cell to become cancerous. Consider what might happen to the cell cycle in a cell with a recently acquired oncogene. In most instances, the alteration of the DNA sequence will result in a less functional (or nonfunctional) protein. The result is detrimental to the cell and will likely prevent the cell from completing the cell cycle; however, the organism is not harmed because the mutation will not be carried forward. If a cell cannot reproduce, the mutation is not propagated and the damage is minimal. Occasionally, however, a gene mutation causes a change that increases the activity of a positive regulator. For example, a mutation that allows Cdk to be activated without being partnered with cyclin could push the cell cycle past a checkpoint before all of the required conditions are met. If the resulting daughter cells are too damaged to undergo further cell divisions, the mutation would not be propagated and no harm would come to the organism. However, if the atypical daughter cells are able to undergo further cell divisions, subsequent generations of cells will probably accumulate even more mutations, some possibly in additional genes that regulate the cell cycle.

The Cdk gene in the above example is only one of many genes that are considered proto-oncogenes. In addition to the cell cycle regulatory proteins, any protein that influences the cycle can be altered in such a way as to override cell cycle checkpoints. An oncogene is any gene that, when altered, leads to an increase in the rate of cell cycle progression.

Tumor Suppressor Genes

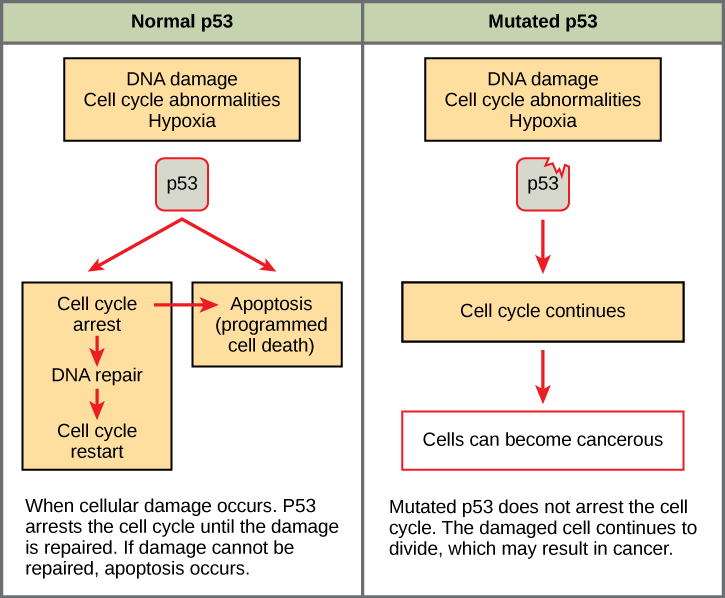

Like proto-oncogenes, many of the negative cell cycle regulatory proteins were discovered in cells that had become cancerous. Tumor suppressor genes are segments of DNA that code for negative regulator proteins, the type of regulators that, when activated, can prevent the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division. The collective function of the best-understood tumor suppressor gene proteins, Rb, p53, and p21, is to put up a roadblock to cell cycle progression until certain events are completed. A cell that carries a mutated form of a negative regulator might not be able to halt the cell cycle if there is a problem. Tumor suppressors are similar to brakes in a vehicle: Malfunctioning brakes can contribute to a car crash.

Mutated p53 genes have been identified in more than one-half of all human tumor cells. This discovery is not surprising in light of the multiple roles that the p53 protein plays at the G1 checkpoint. A cell with a faulty p53 may fail to detect errors present in the genomic DNA (Figure 7.14). Even if a partially functional p53 does identify the mutations, it may no longer be able to signal the necessary DNA repair enzymes. Either way, damaged DNA will remain uncorrected. At this point, a functional p53 will deem the cell unsalvageable and trigger programmed cell death (apoptosis). The damaged version of p53 found in cancer cells, however, cannot trigger apoptosis.

The loss of p53 function has other repercussions for the cell cycle. Mutated p53 might lose its ability to trigger p21 production. Without adequate levels of p21, there is no effective block on Cdk activation. Essentially, without a fully functional p53, the G1 checkpoint is severely compromised and the cell proceeds directly from G1 to S regardless of internal and external conditions. At the completion of this shortened cell cycle, two daughter cells are produced that have inherited the mutated p53 gene. Given the non-optimal conditions under which the parent cell reproduced, it is likely that the daughter cells will have acquired other mutations in addition to the faulty tumor suppressor gene. Cells such as these daughter cells quickly accumulate both oncogenes and non-functional tumor suppressor genes. Again, the result is tumor growth.

Go to this website (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/cancer) to watch an animation of how cancer results from errors in the cell cycle.

7.5 | Prokaryotic Cell Division

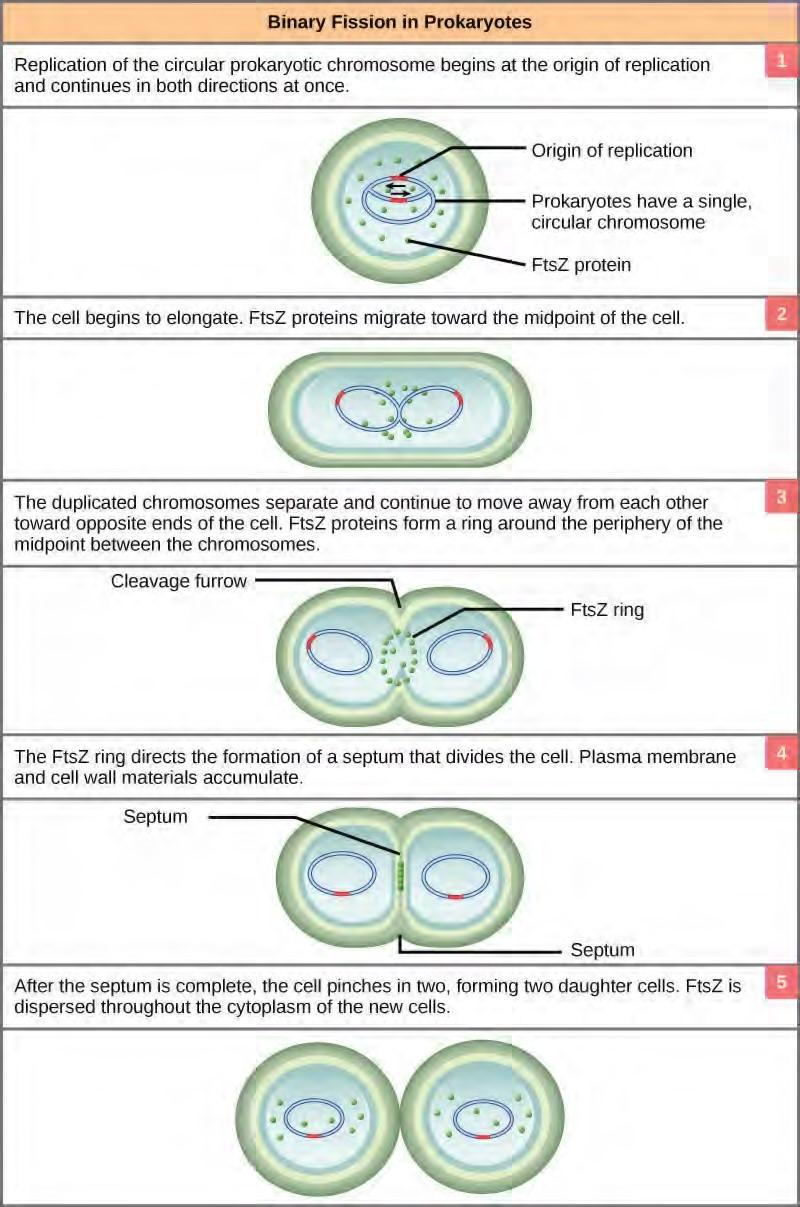

Prokaryotes, such as bacteria, propagate by binary fission. For unicellular organisms, cell division is the only method to produce new individuals. In both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, the outcome of cell reproduction is a pair of daughter cells that are genetically identical to the parent cell. In unicellular organisms, daughter cells are individuals.

To achieve the outcome of cloned offspring, certain steps are essential. The genomic DNA must be replicated and then allocated into the daughter cells; the cytoplasmic contents must also be divided to give both new cells the machinery to sustain life. In bacterial cells, the genome consists of a single, circular DNA chromosome; therefore, the process of cell division is simplified. Karyokinesis is unnecessary because there is no nucleus and thus no need to direct one copy of the multiple chromosomes into each daughter cell. This type of cell division is called binary (prokaryotic) fission.

Binary Fission

Due to the relative simplicity of the prokaryotes, the cell division process, called binary fission, is a less complicated and much more rapid process than cell division in eukaryotes. The single, circular DNA chromosome of bacteria is not enclosed in a nucleus, but instead occupies a specific location, the nucleoid, within the cell (Figure 7.2). Although the DNA of the nucleoid is associated with proteins that aid in packaging the molecule into a compact size, there are no histone proteins and thus no nucleosomes in prokaryotes. The packing proteins of bacteria are, however, related to the cohesin and condensin proteins involved in the chromosome compaction of eukaryotes.

The bacterial chromosome is attached to the plasma membrane at about the midpoint of the cell. The starting point of replication, the origin, is close to the binding site of the chromosome to the plasma membrane (Figure 7.15). Replication of the DNA is bidirectional, moving away from the origin on both strands of the loop simultaneously. As the new double strands are formed, each origin point moves away from the cell wall attachment toward the opposite ends of the cell. As the cell elongates, the growing membrane aids in the transport of the chromosomes. After the chromosomes have cleared the midpoint of the elongated cell, cytoplasmic separation begins. The formation of a ring composed of repeating units of a protein called FtsZ directs the partition between the nucleoids. Formation of the FtsZ ring triggers the accumulation of other proteins that work together to recruit new membrane and cell wall materials to the site. A septum is formed between the nucleoids, extending gradually from the periphery toward the center of the cell. When the new cell walls are in place, the daughter cells separate.

Figure 7.15 These images show the steps of binary fission in prokaryotes. (credit: modification of work by “Mcstrother”/Wikimedia Commons)

7.6 | The Process of Meiosis

Sexual reproduction requires fertilization, the union of two cells from two individual organisms. If those two cells each contain one set of chromosomes, then the resulting cell contains two sets of chromosomes. Haploid cells contain one set of chromosomes. Cells containing two sets of chromosomes are called diploid. The number of sets of chromosomes in a cell is called its ploidy level. If the reproductive cycle is to continue, then the diploid cell must somehow reduce its number of chromosome sets before fertilization can occur again, or there will be a continual doubling in the number of chromosome sets in every generation. So, in addition to fertilization, sexual reproduction includes a nuclear division that reduces the number of chromosome sets.

Most animals and plants are diploid, containing two sets of chromosomes. In each somatic cell of the organism (all cells of a multicellular organism except the gametes or reproductive cells), the nucleus contains two copies of each chromosome, called homologous chromosomes. Somatic cells are sometimes referred to as “body” cells. Homologous chromosomes are matched pairs containing the same genes in identical locations along their length. Diploid organisms inherit one copy of each homologous chromosome from each parent; all together, they are considered a full set of chromosomes. Haploid cells, containing a single copy of each homologous chromosome, are found only within structures that give rise to either gametes or spores. Spores are haploid cells that can produce a haploid organism or can fuse with another spore to form a diploid cell. All animals and most plants produce eggs and sperm, or gametes. Some plants and all fungi produce spores.

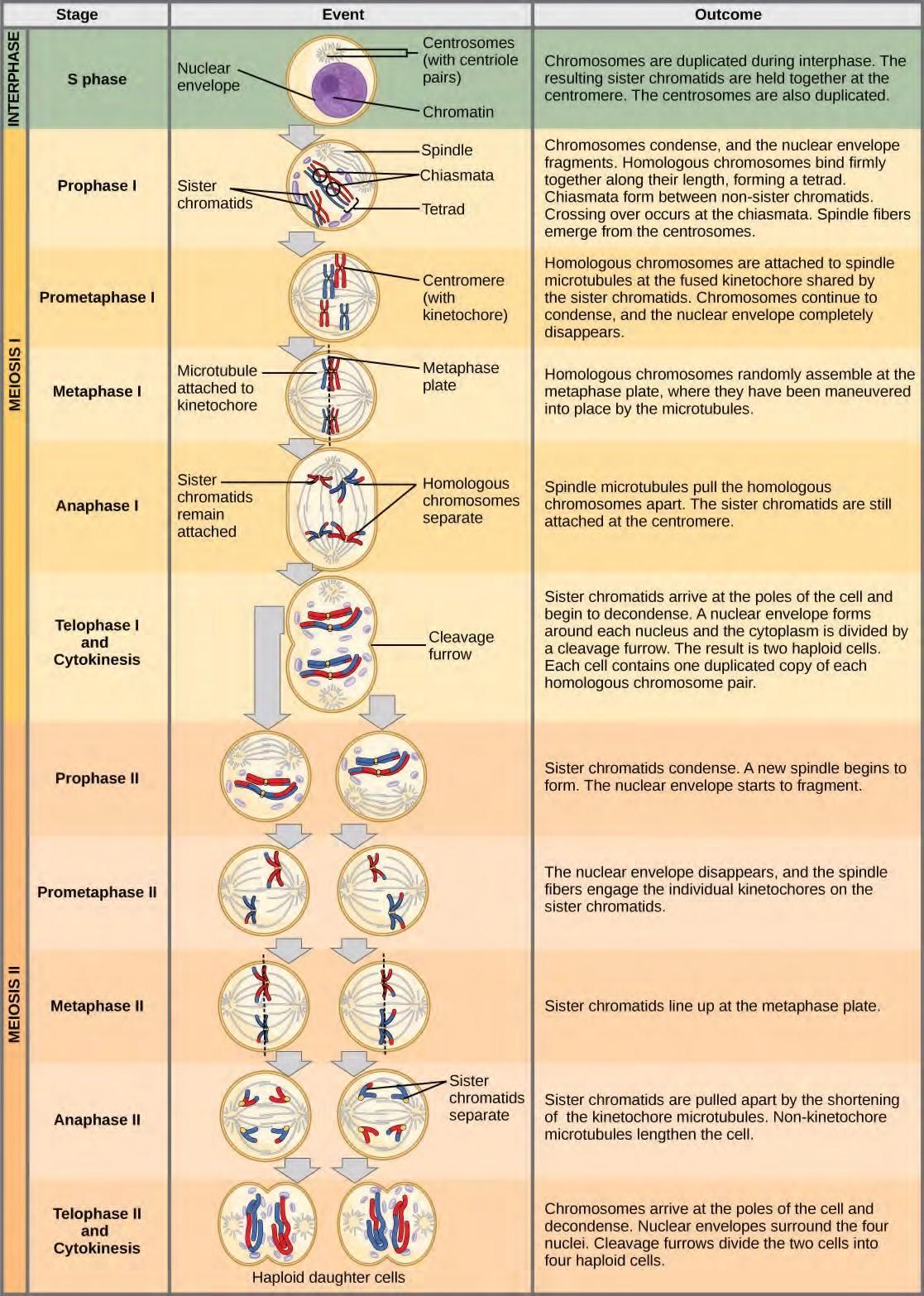

The nuclear division that forms haploid cells, which is called meiosis, is related to mitosis. As you have learned, mitosis is the part of a cell reproduction cycle that results in identical daughter nuclei that are also genetically identical to the original parent nucleus. In mitosis, both the parent and the daughter nuclei are at the same ploidy level—diploid for most plants and animals. Meiosis employs many of the same mechanisms as mitosis. However, the starting nucleus is always diploid and the nuclei that result at the end of a meiotic cell division are haploid. To achieve this reduction in chromosome number, meiosis consists of one round of chromosome duplication and two rounds of nuclear division. Because the events that occur during each of the division stages are analogous to the events of mitosis, the same stage names are assigned. However, because there are two rounds of division, the major process and the stages are designated with a “I” or a “II.” Thus, meiosis I is the first round of meiotic division and consists of prophase I, prometaphase I, and so on. Meiosis II, in which the second round of meiotic division takes place, includes prophase II, prometaphase II, and so on.

Meiosis I

Meiosis is preceded by an interphase consisting of the G1, S, and G2 phases, which are nearly identical to the phases preceding mitosis. The G1 phase, which is also called the first gap phase, is the first phase of the interphase and is focused on cell growth. The S phase is the second phase of interphase, during which the DNA of the chromosomes is replicated. Finally, the G2 phase, also called the second gap phase, is the third and final phase of interphase; in this phase, the cell undergoes the final preparations for meiosis.

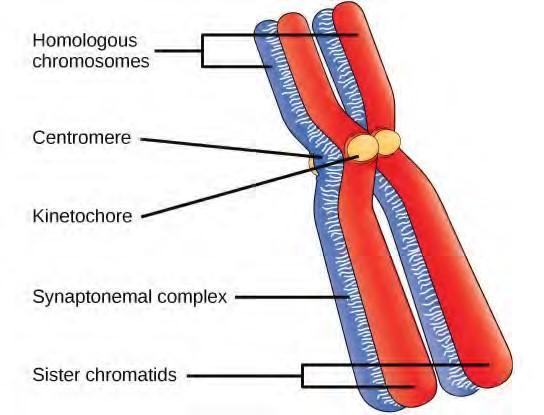

During DNA duplication in the S phase, each chromosome is replicated to produce two identical copies, called sister chromatids, that are held together at the centromere by cohesin proteins. Cohesin holds the chromatids together until anaphase II. The centrosomes, which are the structures that organize the microtubules of the meiotic spindle, also replicate. This prepares the cell to enter prophase I, the first meiotic phase.

Prophase I

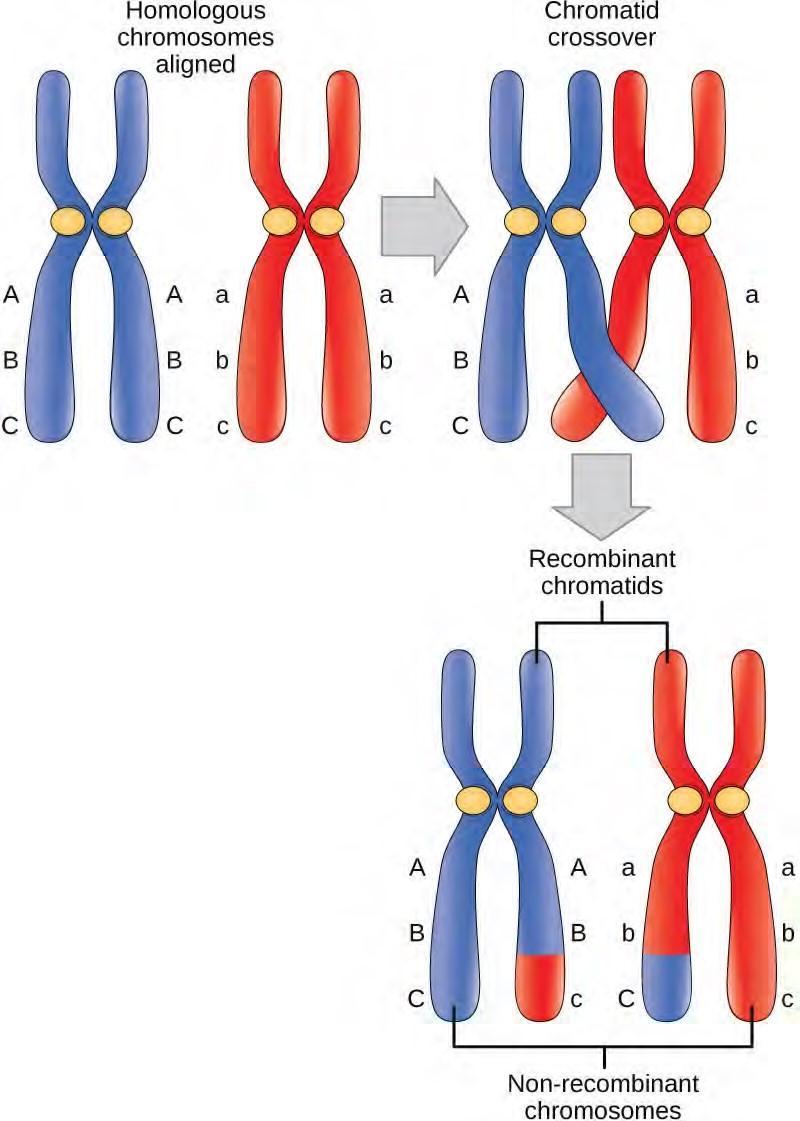

Early in prophase I, before the chromosomes can be seen clearly microscopically, the homologous chromosomes are attached at their tips to the nuclear envelope by proteins. As the nuclear envelope begins to break down, the proteins associated with homologous chromosomes bring the pair close to each other. Recall that, in mitosis, homologous chromosomes do not pair together. In mitosis, homologous chromosomes line up end-to-end so that when they divide, each daughter cell receives a sister chromatid from both members of the homologous pair. The synaptonemal complex, a lattice of proteins between the homologous chromosomes, first forms at specific locations and then spreads to cover the entire length of the chromosomes. The tight pairing of the homologous chromosomes is called synapsis. In synapsis, the genes on the chromatids of the homologous chromosomes are aligned precisely with each other. The synaptonemal complex supports the exchange of chromosomal segments between non-sister homologous chromatids, a process called crossing over. Crossing over can be observed visually after the exchange as chiasmata (singular = chiasma) (Figure 7.16).

In species such as humans, even though the X and Y sex chromosomes are not homologous (most of their genes differ), they have a small region of homology that allows the X and Y chromosomes to pair up during prophase I. A partial synaptonemal complex develops only between the regions of homology.

Figure 7.16 Early in prophase I, homologous chromosomes come together to form a synapse. The chromosomes are bound tightly together and in perfect alignment by a protein lattice called a synaptonemal complex and by cohesin proteins at the centromere.

Located at intervals along the synaptonemal complex are large protein assemblies called recombination nodules. These assemblies mark the points of later chiasmata and mediate the multistep process of crossover—or genetic recombination—between the non-sister chromatids. Near the recombination nodule on each chromatid, the double-stranded DNA is cleaved, the cut ends are modified, and a new connection is made between the non-sister chromatids. As prophase I progresses, the synaptonemal complex begins to break down and the chromosomes begin to condense. When the synaptonemal complex is gone, the homologous chromosomes remain attached to each other at the centromere and at chiasmata. The chiasmata remain until anaphase I. The number of chiasmata varies according to the species and the length of the chromosome. There must be at least one chiasma per chromosome for proper separation of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I, but there may be as many as 25. Following crossover, the synaptonemal complex breaks down and the cohesin connection between homologous pairs is also removed. At the end of prophase I, the pairs are held together only at the chiasmata (Figure 7.17) and are called tetrads because the four sister chromatids of each pair of homologous chromosomes are now visible.

The crossover events are the first source of genetic variation in the nuclei produced by meiosis. A single crossover event between homologous non-sister chromatids leads to a reciprocal exchange of equivalent DNA between a maternal chromosome and a paternal chromosome. Now, when that sister chromatid is moved into a gamete cell it will carry some DNA from one parent of the individual and some DNA from the other parent. The sister recombinant chromatid has a combination of maternal and paternal genes that did not exist before the crossover. Multiple crossovers in an arm of the chromosome have the same effect, exchanging segments of DNA to create recombinant chromosomes.

Figure 7.17 Crossover occurs between non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes. The result is an exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes.

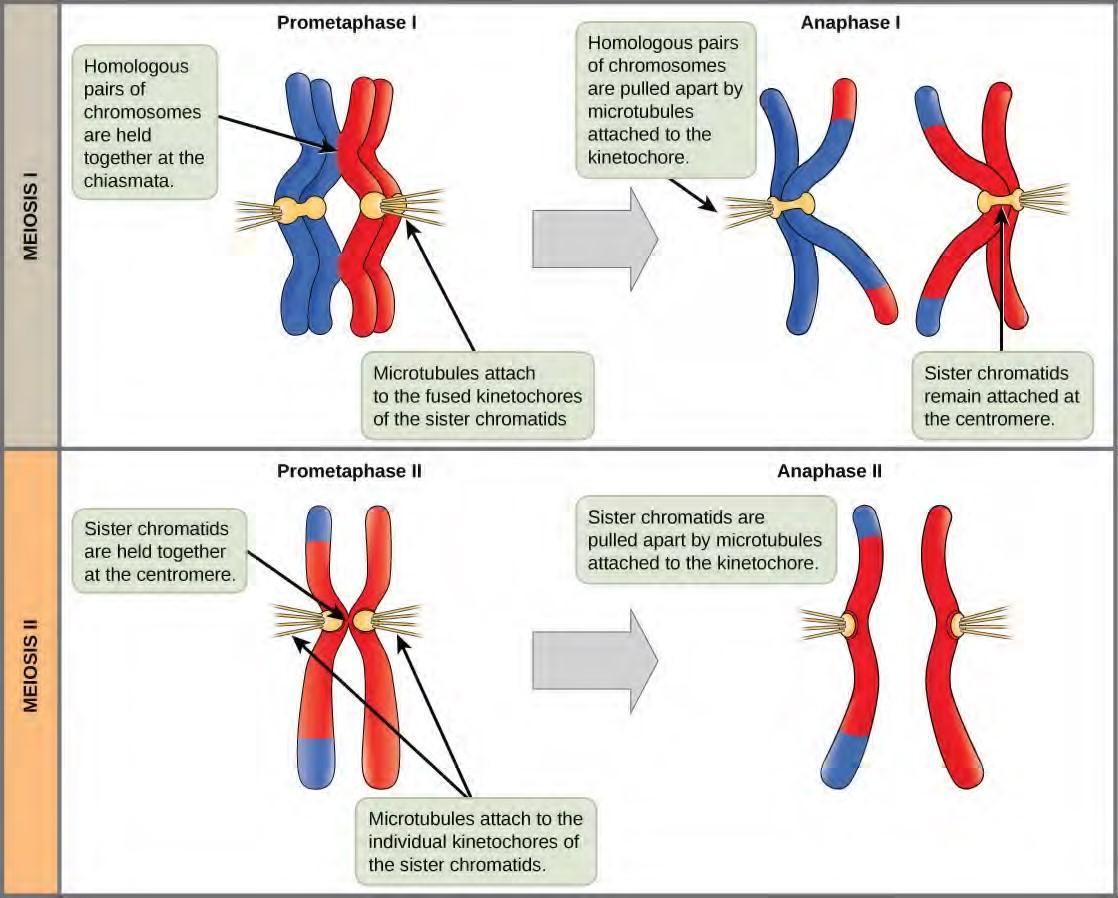

Prometaphase I

The key event in prometaphase I is the attachment of the spindle fiber microtubules to the kinetochore proteins at the centromeres. Kinetochore proteins are multiprotein complexes that bind the centromeres of a chromosome to the microtubules of the mitotic spindle. Microtubules grow from centrosomes placed at opposite poles of the cell. The microtubules move toward the middle of the cell and attach to one of the two fused homologous chromosomes. The microtubules attach at each chromosomes’ kinetochores. With each member of the homologous pair attached to opposite poles of the cell, in the next phase, the microtubules can pull the homologous pair apart. A spindle fiber that has attached to a kinetochore is called a kinetochore microtubule. At the end of prometaphase I, each tetrad is attached to microtubules from both poles, with one homologous chromosome facing each pole. The homologous chromosomes are still held together at chiasmata. In addition, the nuclear membrane has broken down entirely.

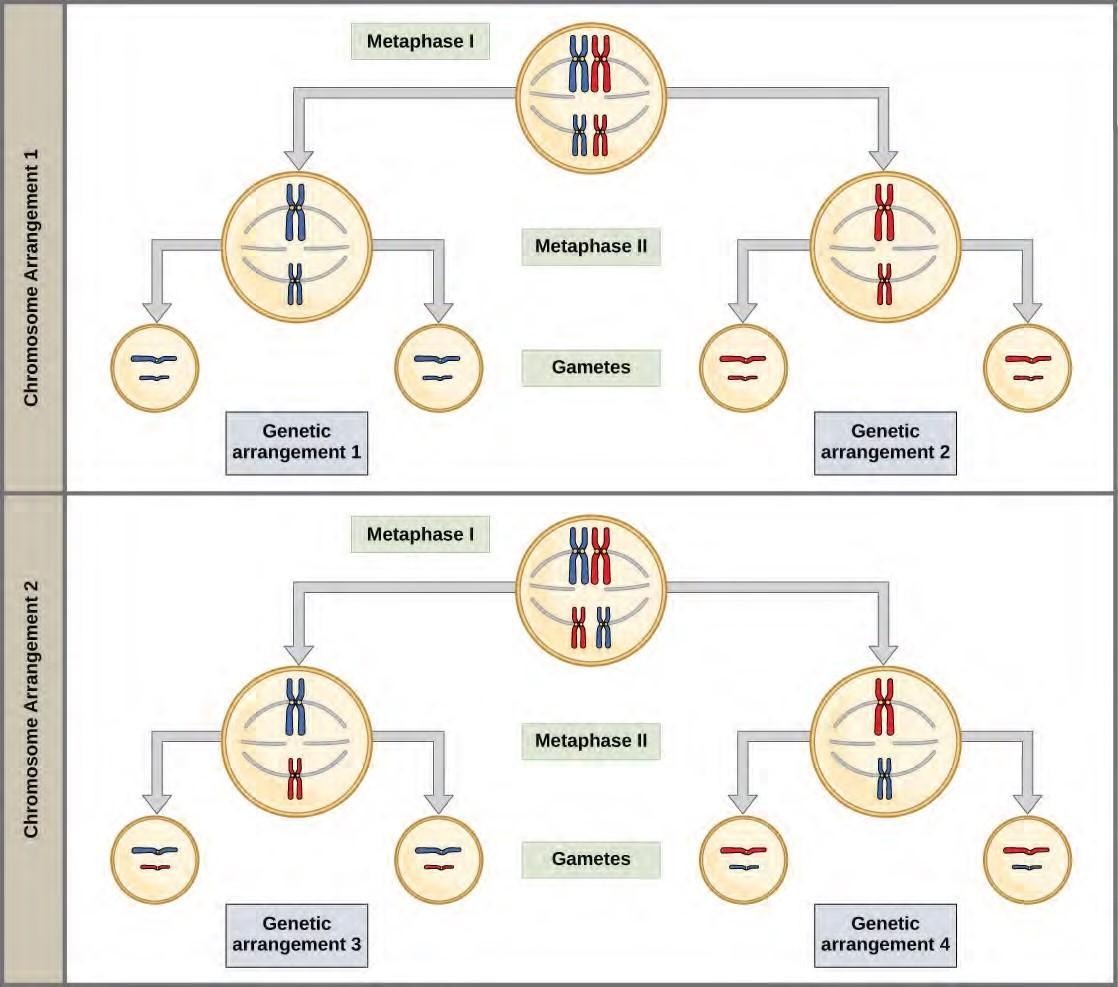

Metaphase I

During metaphase I, the homologous chromosomes are arranged in the center of the cell with the kinetochores facing opposite poles. The homologous pairs orient themselves randomly at the equator. For example, if the two homologous members of chromosome 1 are labeled a and b, then the chromosomes could line up a-b, or b-a. This is important in determining the genes carried by a gamete, as each will only receive one of the two homologous chromosomes. Recall that homologous chromosomes are not identical. They contain slight differences in their genetic information, causing each gamete to have a unique genetic makeup.

This randomness is the physical basis for the creation of the second form of genetic variation in offspring. Consider that the homologous chromosomes of a sexually reproducing organism are originally inherited as two separate sets, one from each parent. Using humans as an example, one set of 23 chromosomes is present in the egg donated by the mother. The father provides the other set of 23 chromosomes in the sperm that fertilizes the egg. Every cell of the multicellular offspring has copies of the original two sets of homologous chromosomes. In prophase I of meiosis, the homologous chromosomes form the tetrads.

In metaphase I, these pairs line up at the midway point between the two poles of the cell to form the metaphase plate. Because there is an equal chance that a microtubule fiber will encounter a maternally or paternally inherited chromosome, the arrangement of the tetrads at the metaphase plate is random. Any maternally inherited chromosome may face either pole. Any paternally inherited chromosome may also face either pole. The orientation of each tetrad is independent of the orientation of the other 22 tetrads.

This event—the random (or independent) assortment of homologous chromosomes at the metaphase plate—is the second mechanism that introduces variation into the gametes or spores. In each cell that undergoes meiosis, the arrangement of the tetrads is different. The number of variations is dependent on the number of chromosomes making up a set. There are two possibilities for orientation at the metaphase plate; the possible number of alignments therefore equals 2n, where n is the number of chromosomes per set. Humans have 23 chromosome pairs, which results in over eight million (223) possible genetically distinct gametes. This number does not include the variability that was previously created in the sister chromatids by crossover. Given these two mechanisms, it is highly unlikely that any two haploid cells resulting from meiosis will have the same genetic composition (Figure 7.18).

To summarize the genetic consequences of meiosis I, the maternal and paternal genes are recombined by crossover events that occur between each homologous pair during prophase I. In addition, the random assortment of tetrads on the metaphase plate produces a unique combination of maternal and paternal chromosomes that will make their way into the gametes.

Figure 7.18 Random, independent assortment during metaphase I can be demonstrated by considering a cell with a set of two chromosomes (n = 2). In this case, there are two possible arrangements at the equatorial plane in metaphase I. The total possible number of different gametes is 2n, where n equals the number of chromosomes in a set. In this example, there are four possible genetic combinations for the gametes. With n = 23 in human cells, there are over 8 million possible combinations of paternal and maternal chromosomes.

Anaphase I

In anaphase I, the microtubules pull the linked chromosomes apart. The sister chromatids remain tightly bound together at the centromere. The chiasmata are broken in anaphase I as the microtubules attached to the fused kinetochores pull the homologous chromosomes apart (Figure 7.19).

Telophase I and Cytokinesis

In telophase, the separated chromosomes arrive at opposite poles. The remainder of the typical telophase events may or may not occur, depending on the species. In some organisms, the chromosomes decondense and nuclear envelopes form around the chromatids in telophase I. In other organisms, cytokinesis—the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells—occurs without reformation of the nuclei. In nearly all species of animals and some fungi, cytokinesis separates the cell contents via a cleavage furrow (constriction of the actin ring that leads to cytoplasmic division). In plants, a cell plate is formed during cell cytokinesis by Golgi vesicles fusing at the metaphase plate. This cell plate will ultimately lead to the formation of cell walls that separate the two daughter cells.

Review the process of meiosis, observing how chromosomes align and migrate, at Meiosis: An Interactive Animation (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/animal_meiosis) .

Meiosis II

In some species, cells enter a brief interphase, or interkinesis, before entering meiosis II. Interkinesis lacks an S phase, so chromosomes are not duplicated. The two cells produced in meiosis I go through the events of meiosis II in synchrony. During meiosis II, the sister chromatids within the two daughter cells separate, forming four new haploid gametes. The mechanics of meiosis II is similar to mitosis, except that each dividing cell has only one set of homologous chromosomes. Therefore, each cell has half the number of sister chromatids to separate out as a diploid cell undergoing mitosis.

Prophase II

If the chromosomes decondensed in telophase I, they condense again. If nuclear envelopes were formed, they fragment into vesicles. The centrosomes that were duplicated during interkinesis move away from each other toward opposite poles, and new spindles are formed.

Prometaphase II

The nuclear envelopes are completely broken down, and the spindle is fully formed. Each sister chromatid forms an individual kinetochore that attaches to microtubules from opposite poles. Metaphase IIThe sister chromatids are maximally condensed and aligned at the equator of the cell.

Anaphase II

The sister chromatids are pulled apart by the kinetochore microtubules and move toward opposite poles. Non-kinetochore microtubules elongate the cell.

Figure 7.19 The process of chromosome alignment differs between meiosis I and meiosis II. In prometaphase I, microtubules attach to the fused kinetochores of homologous chromosomes, and the homologous chromosomes are arranged at the midpoint of the cell in metaphase I. In anaphase I, the homologous chromosomes are separated. In prometaphase II, microtubules attach to the kinetochores of sister chromatids, and the sister chromatids are arranged at the midpoint of the cells in metaphase II. In anaphase II, the sister chromatids are separated.

Telophase II and Cytokinesis

The chromosomes arrive at opposite poles and begin to decondense. Nuclear envelopes form around the chromosomes. Cytokinesis separates the two cells into four unique haploid cells. At this point, the newly formed nuclei are both haploid. The cells produced are genetically unique because of the random assortment of paternal and maternal homologs and because of the recombining of maternal and paternal segments of chromosomes (with their sets of genes) that occurs during crossover. The entire process of meiosis is outlined in Figure 7.20.

Figure 7.20 An animal cell with a diploid number of four (2n = 4) proceeds through the stages of meiosis to form four haploid daughter cells.

7.7 | Comparing Meiosis and Mitosis

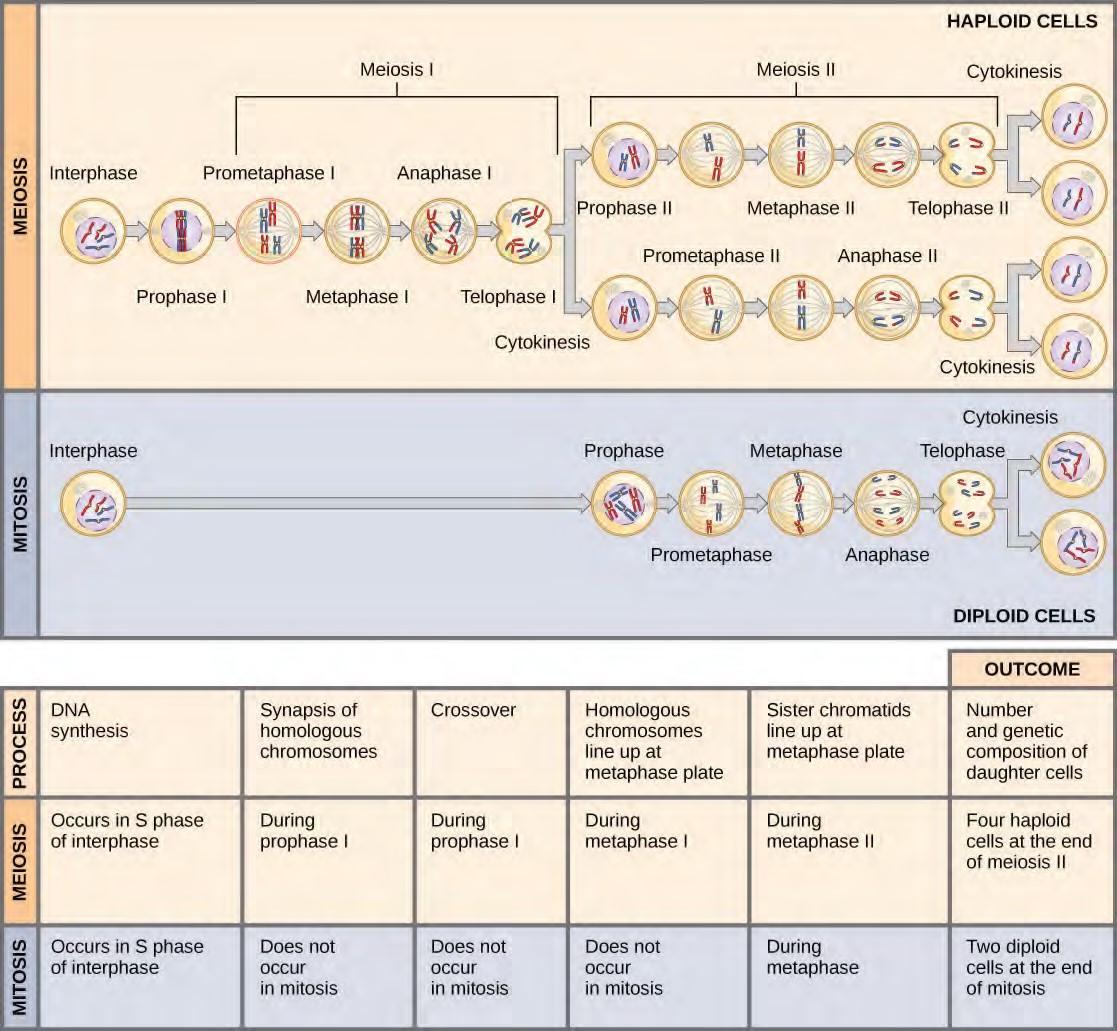

Mitosis and meiosis are both forms of division of the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. They share some similarities, but also exhibit distinct differences that lead to very different outcomes (Figure 7.20). Mitosis is a single nuclear division that results in two nuclei that are usually partitioned into two new cells. The nuclei resulting from a mitotic division are genetically identical to the original nucleus. They have the same number of sets of chromosomes, one set in the case of haploid cells and two sets in the case of diploid cells. In most plants and all animal species, it is typically diploid cells that undergo mitosis to form new diploid cells. In contrast, meiosis consists of two nuclear divisions resulting in four nuclei that are usually partitioned into four new cells. The nuclei resulting from meiosis are not genetically identical and they contain one chromosome set only. This is half the number of chromosome sets in the original cell, which is diploid.

The main differences between mitosis and meiosis occur in meiosis I, which is a very different nuclear division than mitosis. In meiosis I, the homologous chromosome pairs become associated with each other, are bound together with the synaptonemal complex, develop chiasmata and undergo crossover between sister chromatids, and line up along the metaphase plate in tetrads with kinetochore fibers from opposite spindle poles attached to each kinetochore of a homolog in a tetrad. All of these events occur only in meiosis I.

Meiosis II is much more analogous to a mitotic division. In this case, the duplicated chromosomes (only one set of them) line up on the metaphase plate with divided kinetochores attached to kinetochore fibers from opposite poles. During anaphase II, as in mitotic anaphase, the kinetochores divide and one sister chromatid—now referred to as a chromosome—is pulled to one pole while the other sister chromatid is pulled to the other pole. If it were not for the fact that there had been crossover, the two products of each individual meiosis II division would be identical (like in mitosis). Instead, they are different because there has always been at least one crossover per chromosome. Meiosis II is not a reduction division because although there are fewer copies of the genome in the resulting cells, there is still one set of chromosomes, as there was at the end of meiosis I.

Figure 7.21 Meiosis and mitosis are both preceded by one round of DNA replication; however, meiosis includes two nuclear divisions. The four daughter cells resulting from meiosis are haploid and genetically distinct. The daughter cells resulting from mitosis are diploid and identical to the parent cell.

Click through the steps of this interactive animation to compare the meiotic process of cell division to that of mitosis: How Cells Divide (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/how_cells_dvide) .

- Adam S. Wilkins and Robin Holliday, “The Evolution of Meiosis from Mitosis,” Genetics 181 (2009): 3–12.

- Marilee A. Ramesh, Shehre-Banoo Malik and John M. Logsdon, Jr, “A Phylogenetic Inventory of Meiotic Genes: Evidence for Sex in Giardia and an Early Eukaryotic Origin of Meiosis,” Current Biology 15 (2005):185–91.

7.8 | Sexual Reproduction

Sexual reproduction was an early evolutionary innovation after the appearance of eukaryotic cells. It appears to have been very successful because most eukaryotes are able to reproduce sexually, and in many animals, it is the only mode of reproduction. And yet, scientists recognize some real disadvantages to sexual reproduction. On the surface, creating offspring that are genetic clones of the parent appears to be a better system. If the parent organism is successfully occupying a habitat, offspring with the same traits would be similarly successful. There is also the obvious benefit to an organism that can produce offspring whenever circumstances are favorable by asexual budding, fragmentation, or asexual eggs. These methods of reproduction do not require another organism of the opposite sex. Indeed, some organisms that lead a solitary lifestyle have retained the ability to reproduce asexually. In addition, in asexual populations, every individual is capable of reproduction. In sexual populations, the males are not producing the offspring themselves, so in theory an asexual population could grow twice as fast.However, multicellular organisms that exclusively depend on asexual reproduction are exceedingly rare. Why is sexuality (and meiosis) so common? This is one of the important unanswered questions in biology and has been the focus of much research beginning in the latter half of the twentieth century. There are several possible explanations, one of which is that the variation that sexual reproduction creates among offspring is very important to the survival and reproduction of the population. Thus, on average, a sexually reproducing population will leave more descendants than an otherwise similar asexually reproducing population. The only source of variation in asexual organisms is mutation. This is the ultimate source of variation in sexual organisms, but in addition, those different mutations are continually reshuffled from one generation to the next when different parents combine their unique genomes and the genes are mixed into different combinations by crossovers during prophase I and random assortment at metaphase I.

KEY TERMS

anaphase stage of mitosis during which sister chromatids are separated from each other

binary fission prokaryotic cell division process

cell cycle ordered sequence of events that a cell passes through between one cell division and the next

cell cycle ordered series of events involving cell growth and cell division that produces two new daughter cells

cell cycle checkpoint mechanism that monitors the preparedness of a eukaryotic cell to advance through the various cell cycle stages

cell plate structure formed during plant cell cytokinesis by Golgi vesicles, forming a temporary structure (phragmoplast) and fusing at the metaphase plate; ultimately leads to the formation of cell walls that separate the two daughter cells

centriole rod-like structure constructed of microtubules at the center of each animal cell centrosome

centromere region at which sister chromatids are bound together; a constricted area in condensed chromosomes

chromatid single DNA molecule of two strands of duplicated DNA and associated proteins held together at the centromere

cleavage furrow constriction formed by an actin ring during cytokinesis in animal cells that leads to cytoplasmic division

condensin proteins that help sister chromatids coil during prophase

cyclin one of a group of proteins that act in conjunction with cyclin-dependent kinases to help regulate the cell cycle by phosphorylating key proteins; the concentrations of cyclins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle

cyclin-dependent kinase one of a group of protein kinases that helps to regulate the cell cycle when bound to cyclin; it functions to phosphorylate other proteins that are either activated or inactivated by phosphorylation

cytokinesis division of the cytoplasm following mitosis that forms two daughter cells.

diploid cell, nucleus, or organism containing two sets of chromosomes (2n)

G0 phase distinct from the G1 phase of interphase; a cell in G0 is not preparing to divide

G1 phase (also, first gap) first phase of interphase centered on cell growth during mitosis

G2 phase (also, second gap) third phase of interphase during which the cell undergoes final preparations for mitosis

gamete haploid reproductive cell or sex cell (sperm, pollen grain, or egg)

gene physical and functional unit of heredity, a sequence of DNA that codes for a protein.

genome total genetic information of a cell or organism

haploid cell, nucleus, or organism containing one set of chromosomes (n)

histone one of several similar, highly conserved, low molecular weight, basic proteins found in the chromatin of all eukaryotic cells; associates with DNA to form nucleosomes

homologous chromosomes chromosomes of the same morphology with genes in the same location; diploid organisms have pairs of homologous chromosomes (homologs), with each homolog derived from a different parent

interphase period of the cell cycle leading up to mitosis; includes G1, S, and G2 phases (the interim period between two consecutive cell divisions

karyokinesis mitotic nuclear division

kinetochore protein structure associated with the centromere of each sister chromatid that attracts and binds spindle microtubules during prometaphase

locus position of a gene on a chromosome

metaphase stage of mitosis during which chromosomes are aligned at the metaphase plate

metaphase plate equatorial plane midway between the two poles of a cell where the chromosomes align during metaphase

mitosis (also, karyokinesis) period of the cell cycle during which the duplicated chromosomes are separated into identical nuclei; includes prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase

mitotic phase period of the cell cycle during which duplicated chromosomes are distributed into two nuclei and cytoplasmic contents are divided; includes karyokinesis (mitosis) and cytokinesis

mitotic spindle apparatus composed of microtubules that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis

nucleosome subunit of chromatin composed of a short length of DNA wrapped around a core of histone proteins

oncogene mutated version of a normal gene involved in the positive regulation of the cell cycle

origin (also, ORI) region of the prokaryotic chromosome where replication begins (origin of replication)

p21 cell cycle regulatory protein that inhibits the cell cycle; its levels are controlled by p53

p53 cell cycle regulatory protein that regulates cell growth and monitors DNA damage; it halts the progression of the cell cycle in cases of DNA damage and may induce apoptosis

prometaphase stage of mitosis during which the nuclear membrane breaks down and mitotic spindle fibers attach to kinetochores

prophase stage of mitosis during which chromosomes condense and the mitotic spindle begins to form proto-oncogene normal gene that when mutated becomes an oncogene

quiescent refers to a cell that is performing normal cell functions and has not initiated preparations for cell division

retinoblastoma protein (Rb) regulatory molecule that exhibits negative effects on the cell cycle by interacting with a transcription factor (E2F)

S phase second, or synthesis, stage of interphase during which DNA replication occurs

septum structure formed in a bacterial cell as a precursor to the separation of the cell into two daughter cells

telophase stage of mitosis during which chromosomes arrive at opposite poles, decondense, and are surrounded by a new nuclear envelope

tumor suppressor gene segment of DNA that codes for regulator proteins that prevent the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division

chiasmata (singular, chiasma) the structure that forms at the crossover points after genetic material is exchanged

cohesin proteins that form a complex that seals sister chromatids together at their centromeres until anaphase II of meiosis

crossover exchange of genetic material between non-sister chromatids resulting in chromosomes that incorporate genes from both parents of the organism

diploid-dominant life-cycle type in which the multicellular diploid stage is prevalent

fertilization union of two haploid cells from two individual organisms

gametophyte a multicellular haploid life-cycle stage that produces gametes germ cells specialized cell line that produces gametes, such as eggs or sperm

haploid-dominant life-cycle type in which the multicellular haploid stage is prevalent

interkinesis (also, interphase II) brief period of rest between meiosis I and meiosis II

life cycle the sequence of events in the development of an organism and the production of cells that produce offspring

meiosis a nuclear division process that results in four haploid cells

meiosis I first round of meiotic cell division; referred to as reduction division because the ploidy level is reduced from diploid to haploid

meiosis II second round of meiotic cell division following meiosis I; sister chromatids are separated into individual chromosomes, and the result is four unique haploid cells

recombination nodules protein assemblies formed on the synaptonemal complex that mark the points of crossover events and mediate the multistep process of genetic recombination between non-sister chromatids

reduction division nuclear division that produces daughter nuclei each having one-half as many chromosome sets as the parental nucleus; meiosis I is a reduction division

somatic cell all the cells of a multicellular organism except the gametes or reproductive cells

spore haploid cell that can produce a haploid multicellular organism or can fuse with another spore to form a diploid cell

sporophyte a multicellular diploid life-cycle stage that produces haploid spores by meiosis

synapsis formation of a close association between homologous chromosomes during prophase I

synaptonemal complex protein lattice that forms between homologous chromosomes during prophase I, supporting crossover

tetrad two duplicated homologous chromosomes (four chromatids) bound together by chiasmata during prophase I

CHAPTER SUMMARY

7.1 Cell Division

Prokaryotes have a single circular chromosome composed of double-stranded DNA, whereas eukaryotes have multiple, linear chromosomes composed of chromatin surrounded by a nuclear membrane. The 46 chromosomes of human somatic cells are composed of 22 pairs of autosomes (matched pairs) and a pair of sex chromosomes, which may or may not be matched. This is the 2n or diploid state. Human gametes have 23 chromosomes or one complete set of chromosomes; a set of chromosomes is complete with either one of the sex chromosomes. This is the n or haploid state. Genes are segments of DNA that code for a specific protein. An organism’s traits are determined by the genes inherited from each parent. Duplicated chromosomes are composed of two sister chromatids. Chromosomes are compacted using a variety of mechanisms during certain stages of the cell cycle. Several classes of protein are involved in the organization and packing of the chromosomal DNA into a highly condensed structure. The condensing complex compacts chromosomes, and the resulting condensed structure is necessary for chromosomal segregation during mitosis.

7.2 The Cell Cycle

The cell cycle is an orderly sequence of events. Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of precisely timed and carefully regulated stages. In eukaryotes, the cell cycle consists of a long preparatory period, called interphase. Interphase is divided into G1, S, and G2 phases. The mitotic phase begins with karyokinesis (mitosis), which consists of five stages: prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. The final stage of the mitotic phase is cytokinesis, during which the cytoplasmic components of the daughter cells are separated either by an actin ring (animal cells) or by cell plate formation (plant cells).

7.3 Control of the Cell Cycle

Each step of the cell cycle is monitored by internal controls called checkpoints. There are three major checkpoints in the cell cycle: one near the end of G1, a second at the G2/M transition, and the third during metaphase. Positive regulator molecules allow the cell cycle to advance to the next stage. Negative regulator molecules monitor cellular conditions and can halt the cycle until specific requirements are met.

7.4 Cancer and the Cell Cycle

Cancer is the result of unchecked cell division caused by a breakdown of the mechanisms that regulate the cell cycle. The loss of control begins with a change in the DNA sequence of a gene that codes for one of the regulatory molecules. Faulty instructions lead to a protein that does not function as it should.

Any disruption of the monitoring system can allow other mistakes to be passed on to the daughter cells. Each successive cell division will give rise to daughter cells with even more accumulated damage. Eventually, all checkpoints become nonfunctional, and rapidly reproducing cells crowd out normal cells, resulting in a tumor or leukemia (blood cancer).

7.5 Prokaryotic Cell Division

In both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell division, the genomic DNA is replicated and then each copy is allocated into a daughter cell. In addition, the cytoplasmic contents are divided evenly and distributed to the new cells. However, there are many differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell division. Bacteria have a single, circular DNA chromosome but no nucleus. Therefore, mitosis is not necessary in bacterial cell division. Bacterial cytokinesis is directed by a ring composed of a protein called FtsZ. Ingrowth of membrane and cell wall material from the periphery of the cells results in the formation of a septum that eventually constructs the separate cell walls of the daughter cells.

7.6 The Process of Meiosis

Sexual reproduction requires that diploid organisms produce haploid cells that can fuse during fertilization to form diploid offspring. As with mitosis, DNA replication occurs prior to meiosis during the S-phase of the cell cycle. Meiosis is a series of events that arrange and separate chromosomes and chromatids into daughter cells. During the interphases of meiosis, each chromosome is duplicated. In meiosis, there are two rounds of nuclear division resulting in four nuclei and usually four daughter cells, each with half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The first separates homologs, and the second—like mitosis—separates chromatids into individual chromosomes. During meiosis, variation in the daughter nuclei is introduced because of crossover in prophase I and random alignment of tetrads at metaphase I. The cells that are produced by meiosis are genetically unique.

Meiosis and mitosis share similarities, but have distinct outcomes. Mitotic divisions are single nuclear divisions that produce daughter nuclei that are genetically identical and have the same number of chromosome sets as the original cell. Meiotic divisions include two nuclear divisions that produce four daughter nuclei that are genetically different and have one chromosome set instead of the two sets of chromosomes in the parent cell. The main differences between the processes occur in the first division of meiosis, in which homologous chromosomes are paired and exchange non-sister chromatid segments. The homologous chromosomes separate into different nuclei during meiosis I, causing a reduction of ploidy level in the first division. The second division of meiosis is more similar to a mitotic division, except that the daughter cells do not contain identical genomes because of crossover.

7.7 Sexual Reproduction

Nearly all eukaryotes undergo sexual reproduction. The variation introduced into the reproductive cells by meiosis appears to be one of the advantages of sexual reproduction that has made it so successful. Meiosis and fertilization alternate in sexual life cycles. The process of meiosis produces unique reproductive cells called gametes, which have half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. Fertilization, the fusion of haploid gametes from two individuals, restores the diploid condition. Thus, sexually reproducing organisms alternate between haploid and diploid stages. However, the ways in which reproductive cells are produced and the timing between meiosis and fertilization vary greatly. There are three main categories of life cycles: diploid-dominant, demonstrated by most animals; haploid-dominant, demonstrated by all fungi and some algae; and the alternation of generations, demonstrated by plants and some algae.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

A diploid cell has_______ the number of chromosomes as a haploid cell.

one-fourth

half

twice

four times

An organism’s traits are determined by the specific combination of inherited _____.

cells.

genes.

proteins.

chromatids.

The first level of DNA organization in a eukaryotic cell is maintained by which molecule?

cohesin

condensin

chromatin

histone

Identical copies of chromatin held together by cohesin at the centromere are called _____.

histones.

nucleosomes.

chromatin.

sister chromatids.

Chromosomes are duplicated during what stage of the cell cycle?

G1 phase

S phase

prophase

prometaphase

Which of the following events does not occur during some stages of interphase?

DNA duplication

organelle duplication

increase in cell size

separation of sister chromatids

The mitotic spindles arise from which cell structure?

centromere

centrosome

kinetochore

cleavage furrow

Attachment of the mitotic spindle fibers to the kinetochores is a characteristic of which stage of mitosis?

prophase

prometaphase

metaphase

anaphase

Unpacking of chromosomes and the formation of a new nuclear envelope is a characteristic of which stage of mitosis?

prometaphase

metaphase

anaphase

telophase

Separation of the sister chromatids is a characteristic of which stage of mitosis?

prometaphase

metaphase

anaphase

telophase

The chromosomes become visible under a light microscope during which stage of mitosis?

prophase

prometaphase

metaphase

anaphase

The fusing of Golgi vesicles at the metaphase plate of dividing plant cells forms what structure?

cell plate

actin ring

cleavage furrow

mitotic spindle

At which of the cell cycle checkpoints do external forces have the greatest influence?

G1 checkpoint

G2 checkpoint

M checkpoint

G0 checkpoint

What is the main prerequisite for clearance at the G2 checkpoint?

cell has reached a sufficient size

an adequate stockpile of nucleotides

accurate and complete DNA replication

proper attachment of mitotic spindle fibers to kinetochores

If the M checkpoint is not cleared, what stage of mitosis will be blocked?

prophase

prometaphase

metaphase

anaphase

Which protein is a positive regulator that phosphorylates other proteins when activated?

p53

retinoblastoma protein (Rb)

cyclin

cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)

Many of the negative regulator proteins of the cell cycle were discovered in what type of cells?

gametes

cells in G0

cancer cells

stem cells

Which negative regulatory molecule can trigger cell suicide (apoptosis) if vital cell cycle events do not occur?

p53

p21

retinoblastoma protein (Rb)

cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)

___________ are changes to the order of nucleotides in a segment of DNA that codes for a protein.

Proto-oncogenes

Tumor suppressor genes

Gene mutations

Negative regulators

A gene that codes for a positive cell cycle regulator is called a(n) _____.

kinase inhibitor.

tumor suppressor gene.

proto-oncogene.

oncogene.

A mutated gene that codes for an altered version of Cdk that is active in the absence of cyclin is a(n) _____.

kinase inhibitor.

tumor suppressor gene.

proto-oncogene.

oncogene.

Which molecule is a Cdk inhibitor that is controlled by p53?

cyclin

anti-kinase

Rb

p21

Which eukaryotic cell cycle event is missing in binary fission?

cell growth

DNA duplication

karyokinesis

cytokinesis

Meiosis produces ________ daughter cells.

two haploid

two diploid

four haploid

four diploid

What structure is most important in forming the tetrads?

centromere

synaptonemal complex

chiasma

kinetochore

At which stage of meiosis are sister chromatids separated from each other?

prophase I

prophase II

anaphase I

anaphase II

At metaphase I, homologous chromosomes are connected only at what structures?

chiasmata

recombination nodules

microtubules

kinetochores

Which of the following is not true in regard to crossover?

Spindle microtubules guide the transfer of DNA across the synaptonemal complex.

Non-sister chromatids exchange genetic material.

Chiasmata are formed.

Recombination nodules mark the crossover point.

What phase of mitotic interphase is missing from meiotic interkinesis?

G0 phase

G1 phase

S phase

G2 phase

The part of meiosis that is similar to mitosis is ________.

meiosis I

anaphase I

meiosis II

interkinesis

If a muscle cell of a typical organism has 32 chromosomes, how many chromosomes will be in a gamete of that same organism?

8

16

32

64

What is a likely evolutionary advantage of sexual reproduction over asexual reproduction?

Sexual reproduction involves fewer steps.

There is a lower chance of using up the resources in a given environment.

Sexual reproduction results in variation

in the offspring.

Sexual reproduction is more cost effective.

Which type of life cycle has both a haploid and diploid multicellular stage?

asexual

diploid-dominant

haploid-dominant

alternation of generations

Fungi typically display which type of life cycle?

diploid-dominant

haploid-dominant

alternation of generations