9 Chapter 9: DNA Structure, Protein Synthesis and GMO’s

Chapter Outline

- 9.1 DNA Structure

- 9.2 Basics of DNA Replication

- 9.3 DNA Replication in Prokaryotes

- 9.4 DNA Replication in Eukaryotes

- 9.5 DNA Repair

- 9.6 Genetic Code

- 9.7 Prokaryotic Transcription

- 9.8 Eurkaryotic Transcription

- 9.9 RNA Processing in Eukaryotes

- 9.10 Ribosomes and Protein Synthesis

- 9.11 Regulation of Gene Expression

- 9.12 Prokaryotic Gene Regulation

- 9.13 Eukaryotic Gene Regulation

- 9.14 Eukaryotic Transcription Gene Regulation

- 9.15 Eukaryotic Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation

- 9.16 Eukaryotic Translational and Post-Translational Gene Regulation

- 9.17 Cancer and Gene Regulation

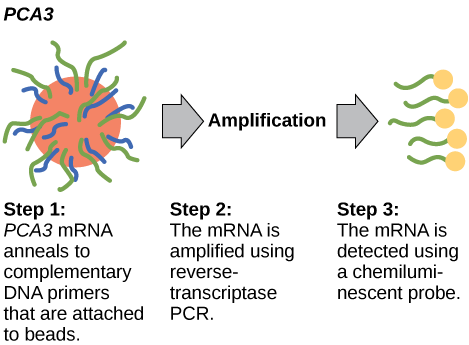

- 9.18 Biotechnology

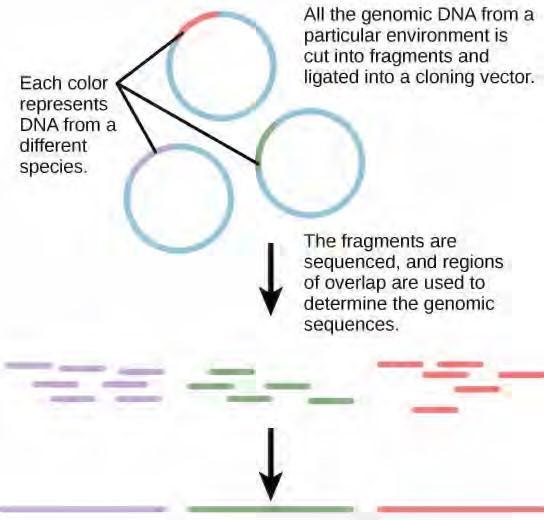

- 9.19 Mapping Genomes

- 9.20 Whole-Genome Sequencing

- 9.21 Applying Genomics

- 9.22 Genomics and Proteomics

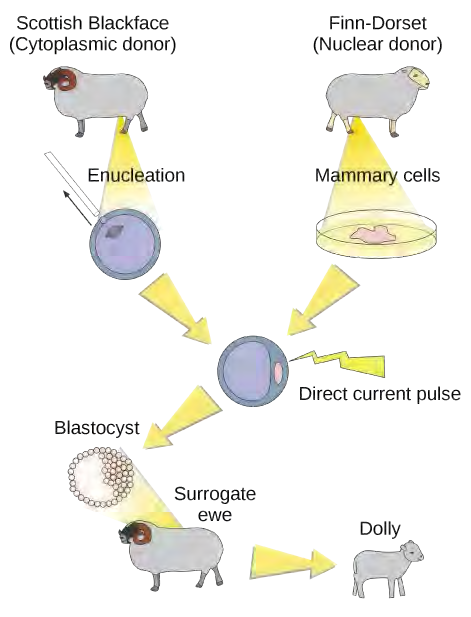

Figure 9.1 Dolly the sheep was the first large mammal to be cloned.

Introduction

The three letters “DNA” have now become synonymous with crime solving, paternity testing, human identification, and genetic testing. DNA can be retrieved from hair, blood, or saliva. Each person’s DNA is unique, and it is possible to detect differences between individuals within a species on the basis of these unique features.

Whereas each cell shares the same genome and DNA sequence, each cell does not turn on, or express, the same set of genes. Each cell type needs a different set of proteins to perform its function. Therefore, only a small subset of proteins is expressed in a cell. For the proteins to be expressed, the DNA must be transcribed into RNA and the RNA must be translated into protein. In a given cell type, not all genes encoded in the DNA are transcribed into RNA or translated into protein because specific cells in our body have specific functions. Specialized proteins that make up the eye (iris, lens, and cornea) are only expressed in the eye, whereas the specialized proteins in the heart (pacemaker cells, heart muscle, and valves) are only expressed in the heart. At any given time, only a subset of all of the genes encoded by our DNA are expressed and translated into proteins. The expression of specific genes is a highly regulated process with many levels and stages of control. This complexity ensures the proper expression in the proper cell at the proper time.

Since the rediscovery of Mendel’s work in 1900, the definition of the gene has progressed from an abstract unit of heredity to a tangible molecular entity capable of replication, expression, and mutation. Genes are composed of DNA and are linearly arranged on chromosomes. Genes specify the sequences of amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. In turn, proteins are responsible for orchestrating nearly every function of the cell. Both genes and the proteins they encode are absolutely essential to life as we know it.

Learning Objectives

You will be able to describe the structure and function of DNA and how it is translated into proteins:

- Explain how DNA is copied to carry the information of heredity

- Describe how DNA is transcribed and translated into proteins:

- Explain how genes in DNA code for proteins

- Identify or diagram how information flows from DNA to protein

- Recognize the process of transcription to make a mRNA from DNA

- Recognize the process of translation to “read” mRNA codons to make a protein

9.1 | DNA Structure

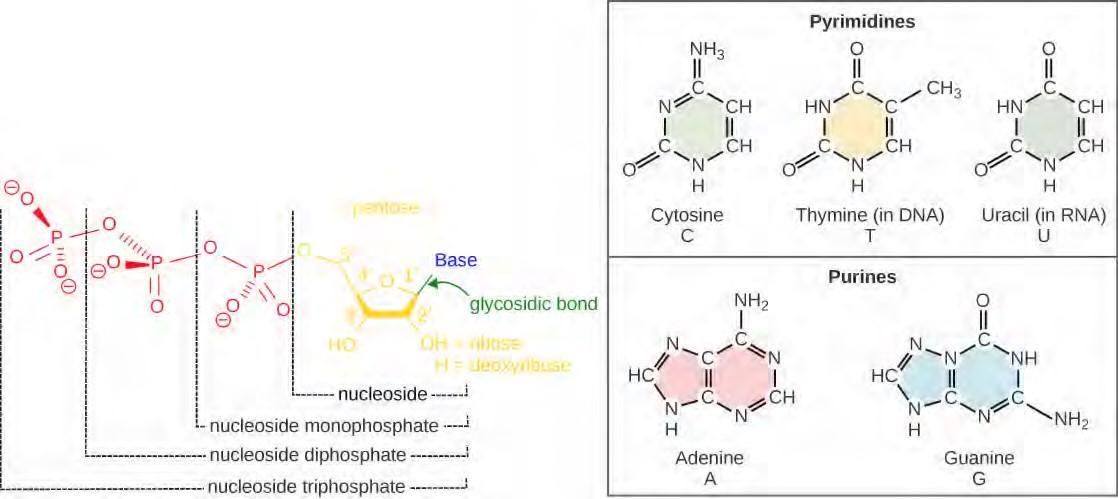

The building blocks of DNA are nucleotides. The important components of the nucleotide are a nitrogenous base, deoxyribose (5-carbon sugar), and a phosphate group (Figure 9.5). The nucleotide is named depending on the nitrogenous base. The nitrogenous base can be a purine such as adenine (A) and guanine (G), or a pyrimidine such as cytosine (C) and thymine (T).

Figure 9.5 Each nucleotide is made up of a sugar, a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base. The sugar is deoxyribose in DNA and ribose in RNA.

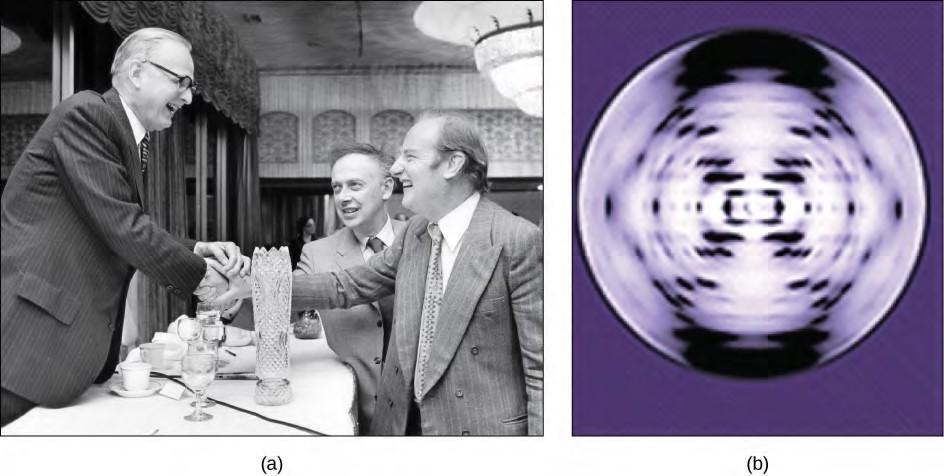

In the 1950s, Francis Crick and James Watson worked together to determine the structure of DNA at the University of Cambridge, England. Other scientists like Linus Pauling and Maurice Wilkins were also actively exploring this field. Pauling had discovered the secondary structure of proteins using X-ray crystallography. In Wilkins’ lab, researcher Rosalind Franklin was using X-ray diffraction methods to understand the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick were able to piece together the puzzle of the DNA molecule on the basis of Franklin’s data because Crick had also studied X-ray diffraction (Figure 9.6). In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Unfortunately, by then Franklin had died, and Nobel prizes are not awarded posthumously.

Figure 9.6 The work of pioneering scientists (a) James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maclyn McCarty led to our present day understanding of DNA. Scientist Rosalind Franklin discovered (b) the X-ray diffraction pattern of DNA, which helped to elucidate its double helix structure. (credit a: modification of work by Marjorie McCarty, Public Library of Science)

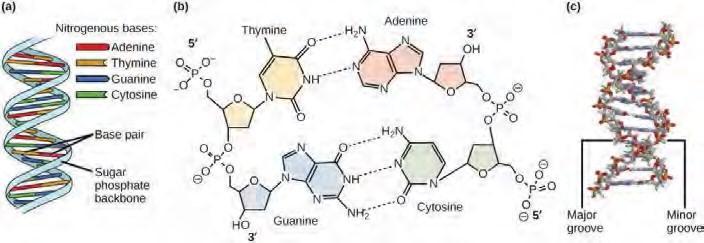

Watson and Crick proposed that DNA is made up of two strands that are twisted around each other to form a right-handed helix. Base pairing takes place between a purine and pyrimidine; namely, A pairs with T and G pairs with C. Adenine and thymine are complementary base pairs, and cytosine and guanine are also complementary base pairs. The base pairs are stabilized by hydrogen bonds; adenine and thymine form two hydrogen bonds and cytosine and guanine form three hydrogen bonds. The two strands are anti-parallel in nature; that is, the 3′ end of one strand faces the 5′ end of the other strand. The sugar and phosphate of the nucleotides form the backbone of the structure, whereas the nitrogenous bases are stacked inside. (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7 DNA has (a) a double helix structure and (b) phosphodiester bonds. The (c) major and minor grooves are binding sites for DNA binding proteins during processes such as transcription (the copying of RNA from DNA) and replication.

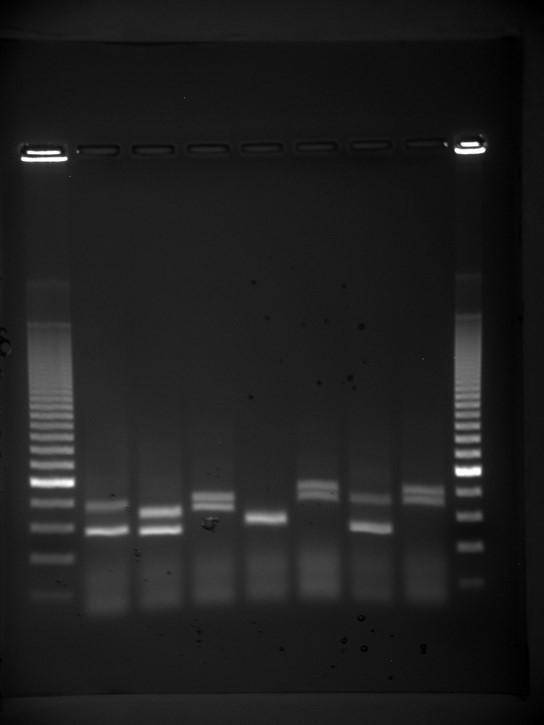

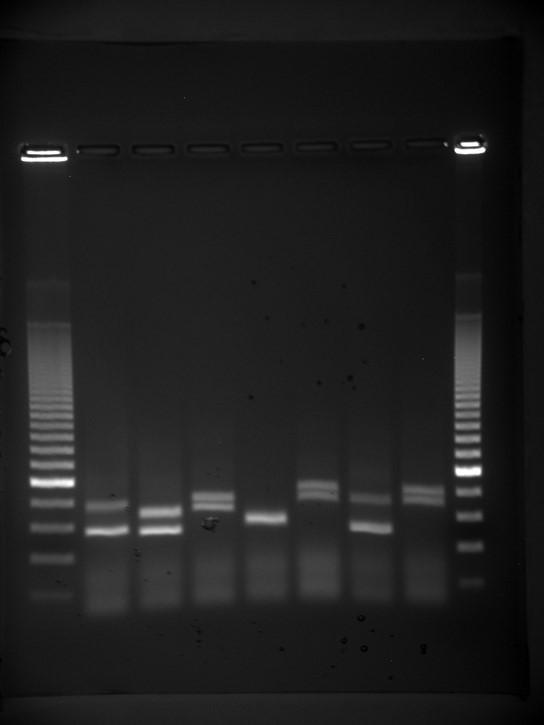

Gel electrophoresis is a technique used to separate DNA fragments of different sizes. Usually the gel is made of a chemical called agarose. The DNA has a net negative charge and moves from the negative electrode toward the positive electrode. The electric current is applied for sufficient time to let the DNA separate according to size; the smallest fragments will be farthest from the well (where the DNA was loaded), and the heavier molecular weight fragments will be closest to the well. Once the DNA is separated, the gel is stained with a DNA-specific dye for viewing it (Figure 9.9).

Figure 9.9 DNA can be separated on the basis of size using gel electrophoresis. (credit: James Jacob, Tompkins Cortland Community College)

Watch Svante Pääbo’s talk (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/neanderthal) explaining the Neanderthal genome research at the 2011 annual TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) conference.

DNA Packaging in Cells

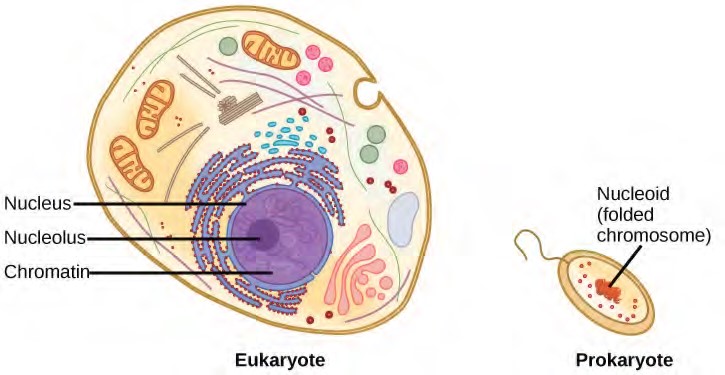

When comparing prokaryotic cells to eukaryotic cells, prokaryotes are much simpler than eukaryotes in many of their features (Figure 9.10). Most prokaryotes contain a single, circular chromosome that is found in an area of the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.

The size of the genome in one of the most well-studied prokaryotes, E.coli, is 4.6 million base pairs (approximately 1.1 mm, if cut and stretched out). So how does this fit inside a small bacterial cell? The DNA is twisted by what is known as supercoiling. Supercoiling means that DNA is either under-wound (less than one turn of the helix per 10 base pairs) or over-wound (more than 1 turn per 10 base pairs) from its normal relaxed state. Some proteins are known to be involved in the supercoiling; other proteins and enzymes such as DNA gyrase help in maintaining the supercoiled structure.

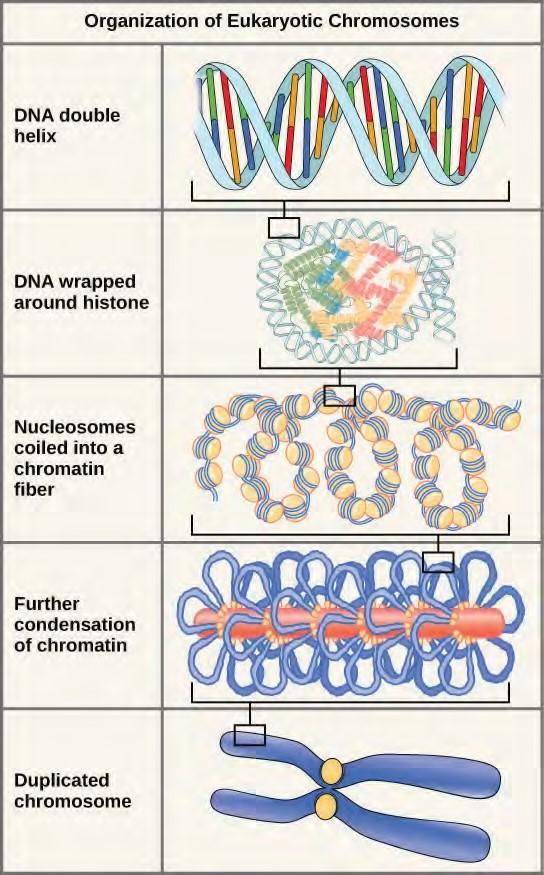

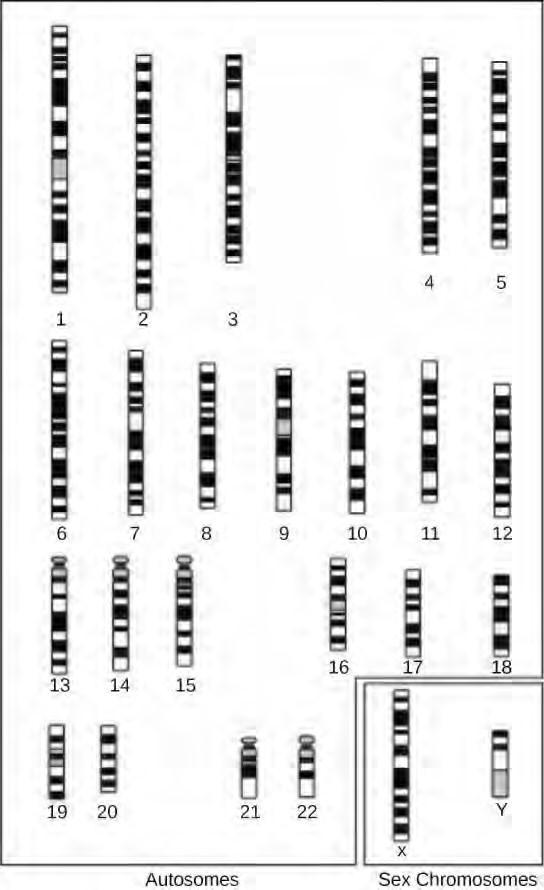

Eukaryotes, whose chromosomes each consist of a linear DNA molecule, employ a different type of packing strategy to fit their DNA inside the nucleus (Figure 9.11). At the most basic level, DNA is wrapped around proteins known as histones to form structures called nucleosomes. The histones are evolutionarily conserved proteins that are rich in basic amino acids and form an octamer. The DNA (which is negatively charged because of the phosphate groups) is wrapped tightly around the histone core. This nucleosome is linked to the next one with the help of a linker DNA. This is also known as the “beads on a string” structure. This is further compacted into a 30 nm fiber, which is the diameter of the structure. At the metaphase stage, the chromosomes are at their most compact, are approximately 700 nm in width, and are found in association with scaffold proteins.In interphase, eukaryotic chromosomes have two distinct regions that can be distinguished by staining. The tightly packaged region is known as heterochromatin, and the less dense region is known as euchromatin. Heterochromatin usually contains genes that are not expressed, and is found in the regions of the centromere and telomeres. The euchromatin usually contains genes that are transcribed, with DNA packaged around nucleosomes but not further compacted.

Figure 9.11 These figures illustrate the compaction of the eukaryotic chromosome.

9.2 | Basics of DNA Replication

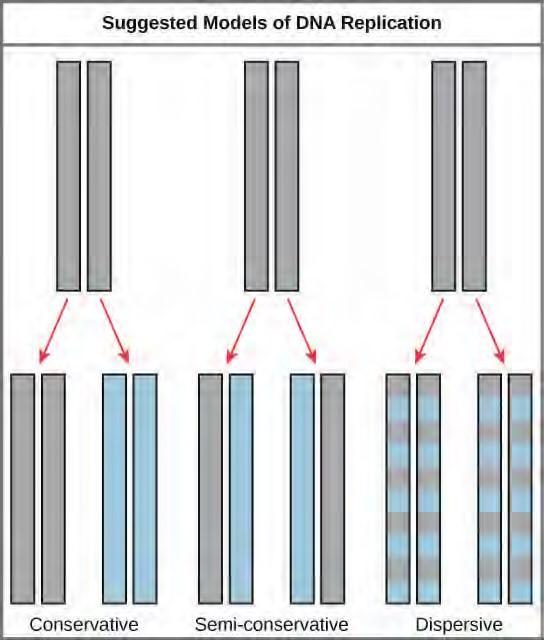

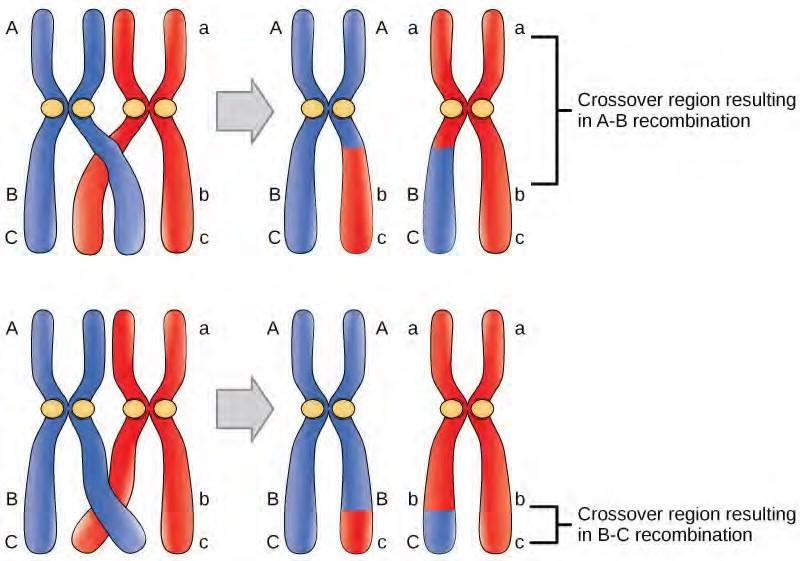

The elucidation of the structure of the double helix provided a hint as to how DNA divides and makes copies of itself. This model suggests that the two strands of the double helix separate during replication, and each strand serves as a template from which the new complementary strand is copied. What was not clear was how the replication took place. There were three models suggested (Figure 9.12): conservative, semi-conservative, and dispersive.

Figure 9.12 The three suggested models of DNA replication. Grey indicates the original DNA strands, and blue indicates newly synthesized DNA.

Click through this tutorial (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/DNA_replicatio2) on DNA replication.

9.3 | DNA Replication in Prokaryotes

DNA replication has been extremely well studied in prokaryotes primarily because of the small size of the genome and the mutants that are available. E. coli has 4.6 million base pairs in a single circular chromosome and all of it gets replicated in approximately 42 minutes, starting from a single origin of replication and proceeding around the circle in both directions. This means that approximately 1000 nucleotides are added per second. The process is quite rapid and occurs without many mistakes.

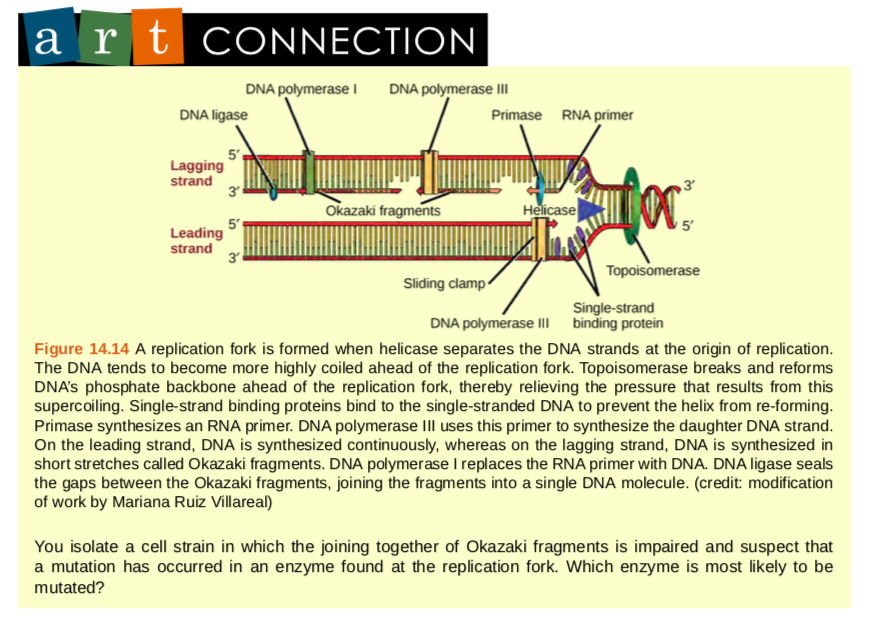

How does the replication machinery know where to begin? It turns out that there are specific nucleotide sequences called origins of replication where replication begins. In E. coli, which has a single origin of replication on its one chromosome (as do most prokaryotes), it is approximately 245 base pairs long and is rich in AT sequences. The origin of replication is recognized by certain proteins that bind to this site. An enzyme called helicase unwinds the DNA by breaking the hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous base pairs. ATP hydrolysis is required for this process. As the DNA opens up, Y-shaped structures called replication forks are formed. Two replication forks are formed at the origin of replication and these get extended bi- directionally as replication proceeds. Single-strand binding proteins coat the single strands of DNA near the replication fork to prevent the single-stranded DNA from winding back into a double helix. DNA polymerase is able to add nucleotides only in the 5′ to 3′ direction (a new DNA strand can be only extended in this direction). It also requires a free 3′-OH group to which it can add nucleotides by forming a phosphodiester bond between the 3′-OH end and the 5′ phosphate of the next nucleotide. This essentially means that it cannot add nucleotides if a free 3′-OH group is not available. Then how does it add the first nucleotide? The problem is solved with the help of a primer that provides the free 3′-OH end. Another enzyme, RNA primase, synthesizes an RNA primer that is about five to ten nucleotides long and complementary to the DNA. Because this sequence primes the DNA synthesis, it is appropriately called the primer. DNA polymerase can now extend this RNA primer, adding nucleotides one by one that are complementary to the template strand (Figure 9.14).

The replication fork moves at the rate of 1000 nucleotides per second. DNA polymerase can only extend in the 5′ to 3′ direction, which poses a slight problem at the replication fork. As we know, the DNA double helix is anti-parallel; that is, one strand is in the 5′ to 3′ direction and the other is oriented in the 3′ to 5′ direction. One strand, which is complementary to the 3′ to 5′ parental DNA strand, is synthesized continuously towards the replication fork because the polymerase can add nucleotides in this direction. This continuously synthesized strand is known as the leading strand. The other strand, complementary to the 5′ to 3′ parental DNA, is extended away from the replication fork, in small fragments known as Okazaki fragments, each requiring a primer to start the synthesis. Okazaki fragments are named after the Japanese scientist who first discovered them. The strand with the Okazaki fragments is known as the lagging strand.The leading strand can be extended by one primer alone, whereas the lagging strand needs a new primer for each of the short Okazaki fragments. The overall direction of the lagging strand will be 3′ to 5′, and that of the leading strand 5′ to 3′. A protein called the sliding clamp holds the DNA polymerase in place as it continues to add nucleotides. The sliding clamp is a ring-shaped protein that binds to the DNA and holds the polymerase in place. Topoisomerase prevents the over-winding of the DNA double helix ahead of the replication fork as the DNA is opening up; it does so by causing temporary nicks in the DNA helix and then resealing it. As synthesis proceeds, the RNA primers are replaced by DNA. The primers are removed by the exonuclease activity of DNA pol I, and the gaps are filled in by deoxyribonucleotides. The nicks that remain between the newly synthesized DNA (that replaced the RNA primer) and the previously synthesized DNA are sealed by the enzyme DNA ligase that catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester linkage between the 3′-OH end of one nucleotide and the 5′ phosphate end of the other fragment. Once the chromosome has been completely replicated, the two DNA copies move into two different cells during cell division.

The process of DNA replication can be summarized as follows:

- DNA unwinds at the origin of replication.

- Helicase opens up the DNA-forming replication forks; these are extended bidirectionally.

- Single-strand binding proteins coat the DNA around the replication fork to prevent rewinding of the DNA.

- Topoisomerase binds at the region ahead of the replication fork to prevent supercoiling.

- Primase synthesizes RNA primers complementary to the DNA strand.

- DNA polymerase starts adding nucleotides to the 3′-OH end of the primer.

- Elongation of both the lagging and the leading strand continues.

- RNA primers are removed by exonuclease activity.

- Gaps are filled by DNA pol by adding dNTPs.

- The gap between the two DNA fragments is sealed by DNA ligase, which helps in the formation of phosphodiester bonds.

Table 9.1 summarizes the enzymes involved in prokaryotic DNA replication and the functions of each.

Prokaryotic DNA Replication: Enzymes and Their Function

|

Enzyme/protein |

Specific Function |

|

DNA pol I |

Exonuclease activity removes RNA primer and replaces with newly synthesized DNA |

|

DNA pol II |

Repair function |

|

DNA pol III |

Main enzyme that adds nucleotides in the 5′-3′ direction |

|

Helicase |

Opens the DNA helix by breaking hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous bases |

|

Ligase |

Seals the gaps between the Okazaki fragments to create one continuous DNA strand |

|

Primase |

Synthesizes RNA primers needed to start replication |

|

Sliding Clamp |

Helps to hold the DNA polymerase in place when nucleotides are being added |

|

Topoisomerase |

Helps relieve the stress on DNA when unwinding by causing breaks and then resealing the DNA |

|

Single-strand binding proteins (SSB) |

Binds to single-stranded DNA to avoid DNA rewinding back. |

Review the full process of DNA replication here (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/replication_DNA) .

9.4 | DNA Replication in Eukaryotes

Eukaryotic genomes are much more complex and larger in size than prokaryotic genomes. The human genome has three billion base pairs per haploid set of chromosomes, and 6 billion base pairs are replicated during the S phase of the cell cycle. There are multiple origins of replication on the eukaryotic chromosome; humans can have up to 100,000 origins of replication. The rate of replication is approximately 100 nucleotides per second, much slower than prokaryotic replication. In yeast, which is a eukaryote, special sequences known as Autonomously Replicating Sequences (ARS) are found on the chromosomes. These are equivalent to the origin of replication in E. coli.

A helicase using the energy from ATP hydrolysis opens up the DNA helix. Replication forks are formed at each replication origin as the DNA unwinds. The opening of the double helix causes overwinding, or supercoiling, in the DNA ahead of the replication fork. These are resolved with the action of topoisomerases. Primers are formed by the enzyme primase, and using the primer, DNA pol can start synthesis. While the leading strand is continuously synthesized by the enzyme pol δ, the lagging strand is synthesized by pol ε. A sliding clamp protein known as PCNA (Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen) holds the DNA pol in place so that it does not slide off the DNA. RNase H removes the RNA primer, which is then replaced with DNA nucleotides. The Okazaki fragments in the lagging strand are joined together after the replacement of the RNA primers with DNA. The gaps that remain are sealed by DNA ligase, which forms the phosphodiester bond.

Telomere replication

Unlike prokaryotic chromosomes, eukaryotic chromosomes are linear. As you’ve learned, the enzyme DNA pol can add nucleotides only in the 5′ to 3′ direction. In the leading strand, synthesis continues until the end of the chromosome is reached. On the lagging strand, DNA is synthesized in short stretches, each of which is initiated by a separate primer. When the replication fork reaches the end of the linear chromosome, there is no place for a primer to be made for the DNA fragment to be copied at the end of the chromosome. These ends thus remain unpaired, and over time these ends may get progressively shorter as cells continue to divide.

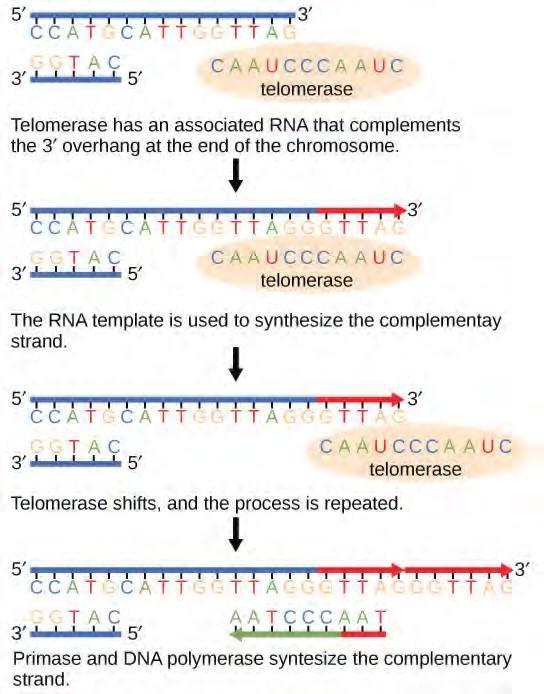

The ends of the linear chromosomes are known as telomeres, which have repetitive sequences that code for no particular gene. In a way, these telomeres protect the genes from getting deleted as cells continue to divide. In humans, a six base pair sequence, TTAGGG, is repeated 100 to 1000 times. The discovery of the enzyme telomerase (Figure 14.16) helped in the understanding of how chromosome ends are maintained. The telomerase enzyme contains a catalytic part and a built-in RNA template. It attaches to the end of the chromosome, and complementary bases to the RNA template are added on the 3′ end of the DNA strand. Once the 3′ end of the lagging strand template is sufficiently elongated, DNA polymerase can add the nucleotides complementary to the ends of the chromosomes. Thus, the ends of the chromosomes are replicated.

Figure 9.15 The ends of linear chromosomes are maintained by the action of the telomerase enzyme.Telomerase is typically active in germ cells and adult stem cells. It is not active in adult somatic cells. For her discovery of telomerase and its action, Elizabeth Blackburn (Figure 9.16) received the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 2009.

Figure 9.16 Elizabeth Blackburn, 2009 Nobel Laureate, is the scientist who discovered how telomerase works. (credit: US Embassy Sweden)

Telomerase and Aging

Cells that undergo cell division continue to have their telomeres shortened because most somatic cells do not make telomerase. This essentially means that telomere shortening is associated with aging. With the advent of modern medicine, preventative health care, and healthier lifestyles, the human life span has increased, and there is an increasing demand for people to look younger and have a better quality of life as they grow older. In 2010, scientists found that telomerase can reverse some age-related conditions in mice. This may have potential in regenerative medicine. Telomerase-deficient mice were used in these studies; these mice have tissue atrophy, stem cell depletion, organ system failure, and impaired tissue injury responses [2]. Telomerase reactivation in these mice caused extension of telomeres, reduced DNA damage, reversed neurodegeneration, and improved the function of the testes, spleen, and intestines. Thus, telomere reactivation may have potential for treating age-related diseases in humans.

2. Jaskelioff et al., “Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice,” Nature 469 (2011): 102-7.

Difference between Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Replication

|

Property |

Prokaryotes |

Eukaryotes |

|

Origin of replication |

Single |

Multiple |

|

Rate of replication |

1000 nucleotides/s |

50 to 100 nucleotides/s |

|

DNA polymerase types |

5 |

14 |

|

Telomerase |

Not present |

Present |

|

RNA primer removal |

DNA pol I |

RNase H |

|

Strand elongation |

DNA pol III |

Pol δ, pol ε |

|

Sliding clamp |

Sliding clamp |

PCNA |

Table 9.2

9.5 | DNA Repair

DNA replication is a highly accurate process, but mistakes can occasionally occur, such as a DNA polymerase inserting a wrong base. Uncorrected mistakes may sometimes lead to serious consequences, such as cancer. Repair mechanisms correct the mistakes. In rare cases, mistakes are not corrected, leading to mutations; in other cases, repair enzymes are themselves mutated or defective.

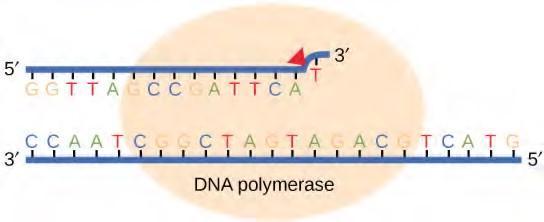

Most of the mistakes during DNA replication are promptly corrected by DNA polymerase by proofreading the base that has been just added (Figure 9.17). In proofreading, the DNA pol reads the newly added base before adding the next one, so a correction can be made. The polymerase checks whether the newly added base has paired correctly with the base in the template strand. If it is the right base, the next nucleotide is added. If an incorrect base has been added, the enzyme makes a cut at the phosphodiester bond and releases the wrong nucleotide. This is performed by the exonuclease action of DNA pol III. Once the incorrect nucleotide has been removed, a new one will be added again.

Figure 9.17 Proofreading by DNA polymerase corrects errors during replication.

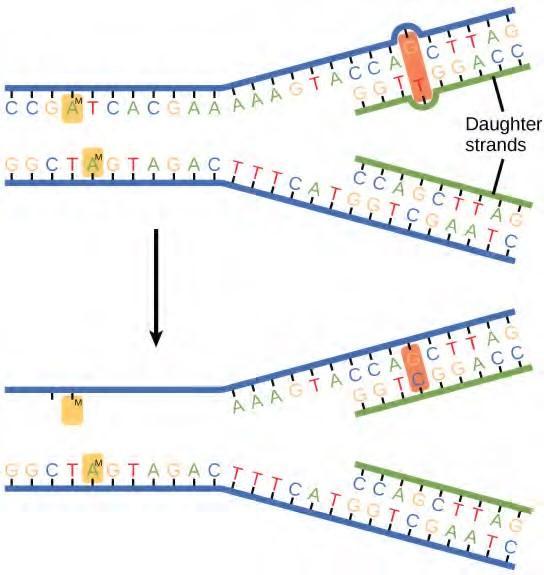

Some errors are not corrected during replication, but are instead corrected after replication is completed; this type of repair is known as mismatch repair (Figure 9.18). The enzymes recognize the incorrectly added nucleotide and excise it; this is then replaced by the correct base. If this remains uncorrected, it may lead to more permanent damage. How do mismatch repair enzymes recognize which of the two bases is the incorrect one? In E. coli, after replication, the nitrogenous base adenine acquires a methyl group; the parental DNA strand will have methyl groups, whereas the newly synthesized strand lacks them. Thus, DNA polymerase is able to remove the wrongly incorporated bases from the newly synthesized, non-methylated strand. In eukaryotes, the mechanism is not very well understood, but it is believed to involve recognition of unsealed nicks in the new strand, as well as a short-term continuing association of some of the replication proteins with the new daughter strand after replication has completed.

Figure 9.18 In mismatch repair, the incorrectly added base is detected after replication. The mismatch repair proteins detect this base and remove it from the newly synthesized strand by nuclease action. The gap is now filled with the correctly paired base.

In another type of repair mechanism, nucleotide excision repair, enzymes replace incorrect bases by making a cut on both the 3′ and 5′ ends of the incorrect base (Figure 9.19). The segment of DNA is removed and replaced with the correctly paired nucleotides by the action of DNA pol. Once the bases are filled in, the remaining gap is sealed with a phosphodiester linkage catalyzed by DNA ligase. This repair mechanism is often employed when UV exposure causes the formation of pyrimidine dimers.

Figure 9.19 Nucleotide excision repairs thymine dimers. When exposed to UV, thymines lying adjacent to each other can form thymine dimers. In normal cells, they are excised and replaced.

A well-studied example of mistakes not being corrected is seen in people suffering from xeroderma pigmentosa (Figure 9.20). Affected individuals have skin that is highly sensitive to UV rays from the sun. When individuals are exposed to UV, pyrimidine dimers, especially those of thymine, are formed; people with xeroderma pigmentosa are not able to repair the damage. These are not repaired because of a defect in the nucleotide excision repair enzymes, whereas in normal individuals, the thymine dimers are excised and the defect is corrected. The thymine dimers distort the structure of the DNA double helix, and this may cause problems during DNA replication. People with xeroderma pigmentosa may have a higher risk of contracting skin cancer than those who don’t have the condition.

Figure 9.20 Xeroderma pigmentosa is a condition in which thymine dimerization from exposure to UV is not repaired. Exposure to sunlight results in skin lesions. (credit: James Halpern et al.)

Errors during DNA replication are not the only reason why mutations arise in DNA. Mutations, variations in the nucleotide sequence of a genome, can also occur because of damage to DNA. Such mutations may be of two types: induced or spontaneous. Induced mutations are those that result from an exposure to chemicals, UV rays, x-rays, or some other environmental agent. Spontaneous mutations occur without any exposure to any environmental agent; they are a result of natural reactions taking place within the body.

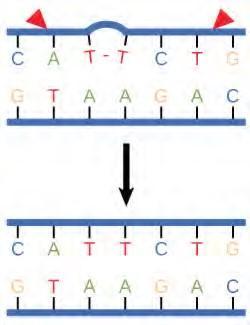

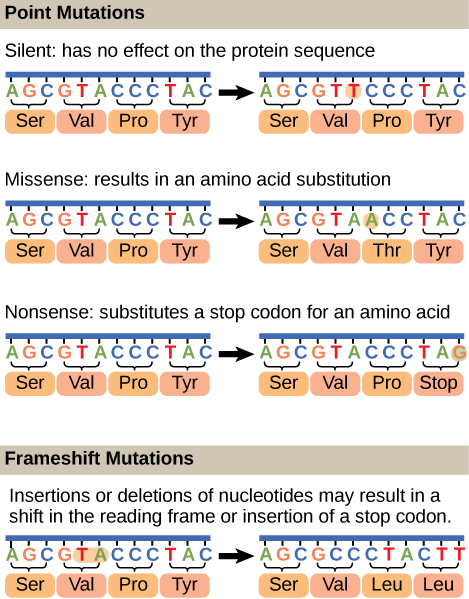

Mutations may have a wide range of effects. Some mutations are not expressed; these are known as silent mutations. Point mutations are those mutations that affect a single base pair. The most common nucleotide mutations are substitutions, in which one base is replaced by another. These can be of two types, either transitions or transversions. Transition substitution refers to a purine or pyrimidine being replaced by a base of the same kind; for example, a purine such as adenine may be replaced by the purine guanine. Transversion substitution refers to a purine being replaced by a pyrimidine, or vice versa; for example, cytosine, a pyrimidine, is replaced by adenine, a purine. Mutations can also be the result of the addition of a base, known as an insertion, or the removal of a base, also known as deletion. Sometimes a piece of DNA from one chromosome may get translocated to another chromosome or to another region of the same chromosome; this is also known as translocation. These mutation types are shown in Figure 9.21.

Mutations in repair genes have been known to cause cancer. Many mutated repair genes have been implicated in certain forms of pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, and colorectal cancer. Mutations can affect either somatic cells or germ cells. If many mutations accumulate in a somatic cell, they may lead to problems such as the uncontrolled cell division observed in cancer. If a mutation takes place in germ cells, the mutation will be passed on to the next generation, as in the case of hemophilia and xeroderma pigmentosa.

9.6 | The Genetic Code

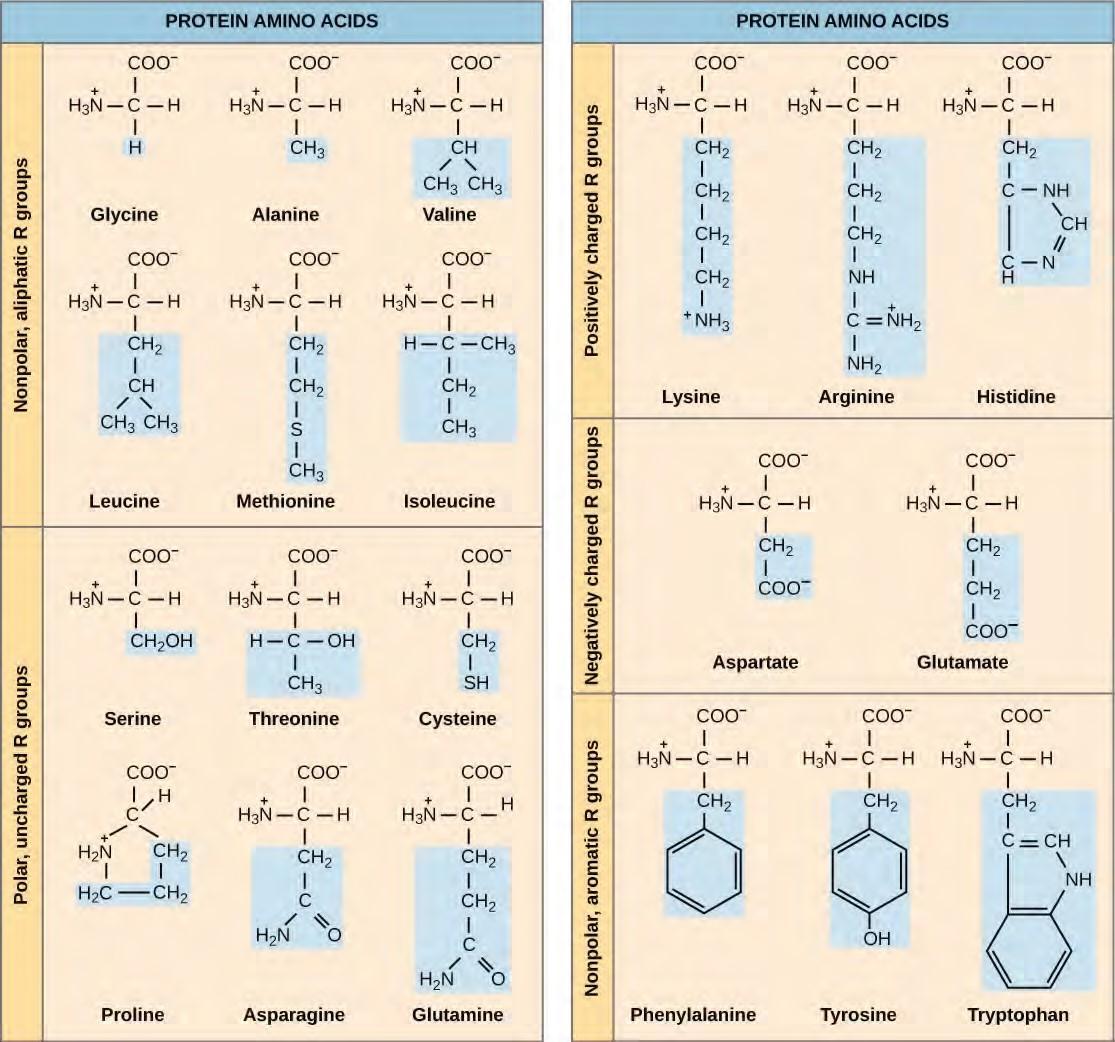

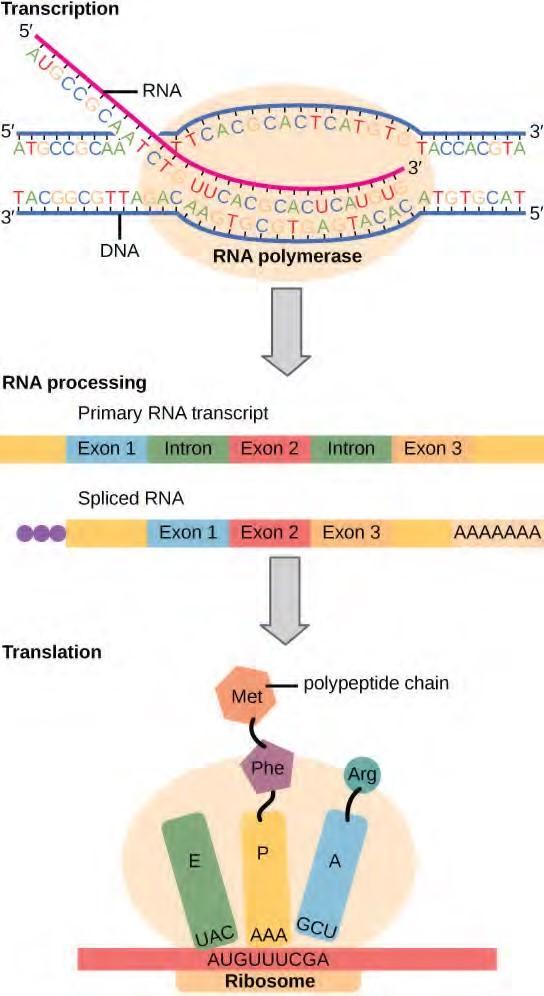

The cellular process of transcription generates messenger RNA (mRNA), a mobile molecular copy of one or more genes with an alphabet of A, C, G, and uracil (U). Translation of the mRNA template converts nucleotide-based genetic information into a protein product. Protein sequences consist of 20 commonly occurring amino acids; therefore, it can be said that the protein alphabet consists of 20 letters (Figure 9.21). Each amino acid is defined by a three-nucleotide sequence called the triplet codon. Different amino acids have different chemistries (such as acidic versus basic, or polar and nonpolar) and different structural constraints. Variation in amino acid sequence gives rise to enormous variation in protein structure and function.

Figure 9.21 Structures of the 20 amino acids found in proteins are shown. Each amino acid is composed of an amino group ( NH+3 ), a carboxyl group (COO–), and a side chain (blue). The side chain may be nonpolar, polar, or charged, as well as large or small. It is the variety of amino acid side chains that gives rise to the incredible variation of protein structure and function.

The Central Dogma: DNA Encodes RNA; RNA Encodes Protein

The flow of genetic information in cells from DNA to mRNA to protein is described by the Central Dogma (Figure 9.22), which states that genes specify the sequence of mRNAs, which in turn specify the sequence of proteins. The decoding of one molecule to another is performed by specific proteins and RNAs. Because the information stored in DNA is so central to cellular function, it makes intuitive sense that the cell would make mRNA copies of this information for protein synthesis, while keeping the DNA itself intact and protected. The copying of DNA to RNA is relatively straightforward, with one nucleotide being added to the mRNA strand for every nucleotide read in the DNA strand. The translation to protein is a bit more complex because three mRNA nucleotides correspond to one amino acid in the polypeptide sequence. However, the translation to protein is still systematic and colinear, such that nucleotides 1 to 3 correspond to amino acid 1, nucleotides 4 to 6 correspond to amino acid 2, and so on.

Figure 9.22 Instructions on DNA are transcribed onto messenger RNA. Ribosomes are able to read the genetic information inscribed on a strand of messenger RNA and use this information to string amino acids together into a protein.

The Genetic Code Is Degenerate and Universal

Given the different numbers of “letters” in the mRNA and protein “alphabets,” scientists theorized that combinations of nucleotides corresponded to single amino acids. Nucleotide doublets would not be sufficient to specify every amino acid because there are only 16 possible two-nucleotide combinations(42).

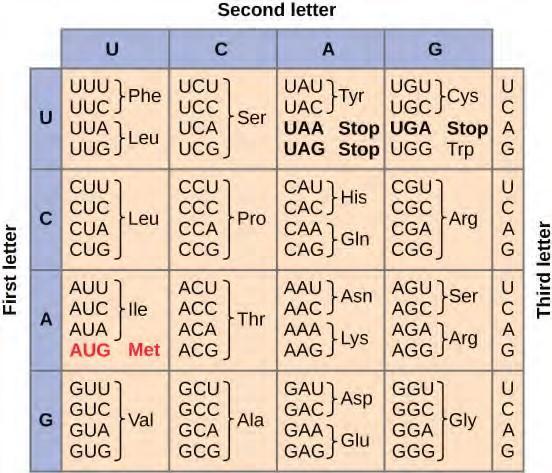

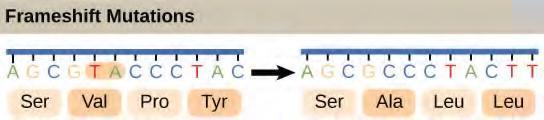

In contrast, there are 64 possible nucleotide triplets (43), which is far more than the number of amino acids. Scientists theorized that amino acids were encoded by nucleotide triplets and that the genetic code was degenerate. In other words, a given amino acid could be encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet. This was later confirmed experimentally; Francis Crick and Sydney Brenner used the chemical mutagen proflavin to insert one, two, or three nucleotides into the gene of a virus. When one or two nucleotides were inserted, protein synthesis was completely abolished. When three nucleotides were inserted, the protein was synthesized and functional. This demonstrated that three nucleotides specify each amino acid. These nucleotide triplets are called codons. The insertion of one or two nucleotides completely changed the triplet reading frame, thereby altering the message for every subsequent amino acid (Figure 9.24). Though insertion of three nucleotides caused an extra amino acid to be inserted during translation, the integrity of the rest of the protein was maintained.Scientists painstakingly solved the genetic code by translating synthetic mRNAs in vitro and sequencing the proteins they specified (Figure 9.23.

Figure 9.23 This figure shows the genetic code for translating each nucleotide triplet in mRNA into an amino acid or a termination signal in a nascent protein. (credit: modification of work by NIH)

The genetic code is universal. With a few exceptions, virtually all species use the same genetic code for protein synthesis. Conservation of codons means that a purified mRNA encoding the globin protein in horses could be transferred to a tulip cell, and the tulip would synthesize horse globin. That there is only one genetic code is powerful evidence that all of life on Earth shares a common origin, especially considering that there are about 1084possible combinations of 20 amino acids and 64 triplet codons.

Transcribe a gene and translate it to protein using complementary pairing and the genetic code at this site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/create_protein) .

Figure 9.25 The deletion of two nucleotides shifts the reading frame of an mRNA and changes the entire protein message, creating a nonfunctional protein or terminating protein synthesis altogether.

Degeneracy is believed to be a cellular mechanism to reduce the negative impact of random mutations. Codons that specify the same amino acid typically only differ by one nucleotide. In addition, amino acids with chemically similar side chains are encoded by similar codons. This nuance of the genetic code ensures that a single-nucleotide substitution mutation might either specify the same amino acid but have no effect or specify a similar amino acid, preventing the protein from being rendered completely nonfunctional.

9.7 | Prokaryotic Transcription

The prokaryotes, which include bacteria and archaea, are mostly single-celled organisms that, by definition, lack membrane-bound nuclei and other organelles. A bacterial chromosome is a covalently closed circle that, unlike eukaryotic chromosomes, is not organized around histone proteins. The central region of the cell in which prokaryotic DNA resides is called the nucleoid. In addition, prokaryotes often have abundant plasmids, which are shorter circular DNA molecules that may only contain one or a few genes. Plasmids can be transferred independently of the bacterial chromosome during cell division and often carry traits such as antibiotic resistance.

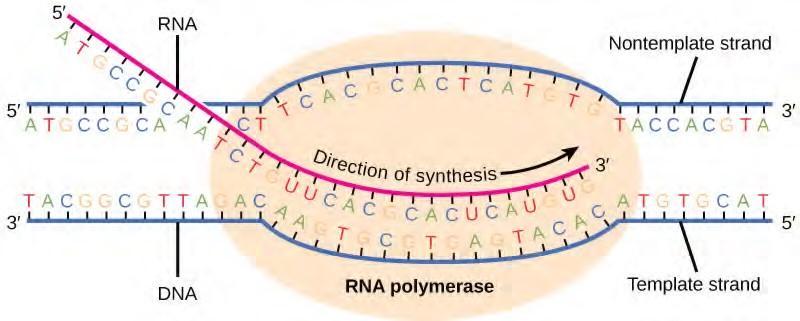

Transcription in prokaryotes (and in eukaryotes) requires the DNA double helix to partially unwind in the region of mRNA synthesis. The region of unwinding is called a transcription bubble. Transcription always proceeds from the same DNA strand for each gene, which is called the template strand. The mRNA product is complementary to the template strand and is almost identical to the other DNA strand, called the nontemplate strand. The only difference is that in mRNA, all of the T nucleotides are replaced with U nucleotides. In an RNA double helix, A can bind U via two hydrogen bonds, just as in A–T pairing in a DNA double helix.

The nucleotide pair in the DNA double helix that corresponds to the site from which the first 5′ mRNA nucleotide is transcribed is called the +1 site, or the initiation site. Nucleotides preceding the initiation site are given negative numbers and are designated upstream. Conversely, nucleotides following the initiation site are denoted with “+” numbering and are called downstream nucleotides.

Initiation of Transcription in Prokaryotes

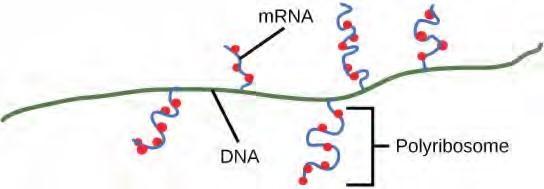

Prokaryotes do not have membrane-enclosed nuclei. Therefore, the processes of transcription, translation, and mRNA degradation can all occur simultaneously. The intracellular level of a bacterial protein can quickly be amplified by multiple transcription and translation events occurring concurrently on the same DNA template. Prokaryotic transcription often covers more than one gene and produces polycistronic mRNAs that specify more than one protein.

Our discussion here will exemplify transcription by describing this process in Escherichia coli, a well-studied bacterial species. Although some differences exist between transcription in E. coli and transcription in archaea, an understanding of E. coli transcription can be applied to virtually all bacterial species.

Prokaryotic RNA Polymerase

Prokaryotes use the same RNA polymerase to transcribe all of their genes. In E. coli, the polymerase is composed of five polypeptide subunits, two of which are identical. Four of these subunits, denoted α, α, β, and β‘ comprise the polymerase core enzyme. These subunits assemble every time a gene is transcribed, and they disassemble once transcription is complete. Each subunit has a unique role; the two α-subunits are necessary to assemble the polymerase on the DNA; the β-subunit binds to the ribonucleoside triphosphate that will become part of the nascent “recently born” mRNA molecule; and the β‘ binds the DNA template strand. The fifth subunit, σ, is involved only in transcription initiation. It confers transcriptional specificity such that the polymerase begins to synthesize mRNA from an appropriate initiation site. Without σ, the core enzyme would transcribe from random sites and would produce mRNA molecules that specified protein gibberish. The polymerase comprised of all five subunits is called the holoenzyme.

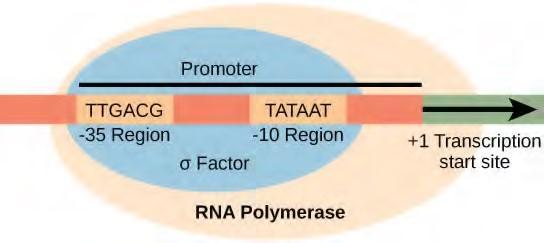

Prokaryotic Promoters

A promoter is a DNA sequence onto which the transcription machinery binds and initiates transcription. In most cases, promoters exist upstream of the genes they regulate. The specific sequence of a promoter is very important because it determines whether the corresponding gene is transcribed all the time, some of the time, or infrequently. Although promoters vary among prokaryotic genomes, a few elements are conserved. At the -10 and -35 regions upstream of the initiation site, there are two promoter consensus sequences, or regions that are similar across all promoters and across various bacterial species (Figure 9.26). The -10 consensus sequence, called the -10 region, is TATAAT. The -35 sequence, TTGACA, is recognized and bound by σ. Once this interaction is made, the subunits of the core enzyme bind to the site. The A–T-rich -10 region facilitates unwinding of the DNA template, and several phosphodiester bonds are made. The transcription initiation phase ends with the production of abortive transcripts, which are polymers of approximately 10 nucleotides that are made and released.

Figure 9.26 The σ subunit of prokaryotic RNA polymerase recognizes consensus sequences found in the promoter region upstream of the transcription start sight. The σ subunit dissociates from the polymerase after transcription has been initiated.

View this MolecularMovies animation (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/transcription) to see the first part of transcription and the base sequence repetition of the TATA box.

Elongation and Termination in Prokaryotes

The transcription elongation phase begins with the release of the σ subunit from the polymerase. The dissociation of σ allows the core enzyme to proceed along the DNA template, synthesizing mRNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction at a rate of approximately 40 nucleotides per second. As elongation proceeds, the DNA is continuously unwound ahead of the core enzyme and rewound behind it (Figure 9.27). The base pairing between DNA and RNA is not stable enough to maintain the stability of the mRNA synthesis components. Instead, the RNA polymerase acts as a stable linker between the DNA template and the nascent RNA strands to ensure that elongation is not interrupted prematurely.

Figure 9.27 During elongation, the prokaryotic RNA polymerase tracks along the DNA template, synthesizes mRNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction, and unwinds and rewinds the DNA as it is read.

Prokaryotic Termination Signals

Once a gene is transcribed, the prokaryotic polymerase needs to be instructed to dissociate from the DNA template and liberate the newly made mRNA. Depending on the gene being transcribed, there are two kinds of termination signals. One is protein-based and the other is RNA-based. Rho-dependent termination is controlled by the rho protein, which tracks along behind the polymerase on the growing mRNA chain. Near the end of the gene, the polymerase encounters a run of G nucleotides on the DNA template and it stalls. As a result, the rho protein collides with the polymerase. The interaction with rho releases the mRNA from the transcription bubble.

Rho-independent termination is controlled by specific sequences in the DNA template strand. As the polymerase nears the end of the gene being transcribed, it encounters a region rich in C–G nucleotides. The mRNA folds back on itself, and the complementary C–G nucleotides bind together. The result is a stable hairpin that causes the polymerase to stall as soon as it begins to transcribe a region rich in A–T nucleotides. The complementary U–A region of the mRNA transcript forms only a weak interaction with the template DNA. This, coupled with the stalled polymerase, induces enough instability for the core enzyme to break away and liberate the new mRNA transcript.

Upon termination, the process of transcription is complete. By the time termination occurs, the prokaryotic transcript would already have been used to begin synthesis of numerous copies of the encoded protein because these processes can occur concurrently. The unification of transcription, translation, and even mRNA degradation is possible because all of these processes occur in the same 5′ to 3′ direction, and because there is no membranous compartmentalization in the prokaryotic cell (Figure 9.28). In contrast, the presence of a nucleus in eukaryotic cells precludes simultaneous transcription and translation.

Figure 9.28 Multiple polymerases can transcribe a single bacterial gene while numerous ribosomes concurrently translate the mRNA transcripts into polypeptides. In this way, a specific protein can rapidly reach a high concentration in the bacterial cell.

Visit this BioStudio animation (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/transcription2) to see the process of prokaryotic transcription.

9.8 | Eukaryotic Transcription

Prokaryotes and eukaryotes perform fundamentally the same process of transcription, with a few key differences. The most important difference between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is the latter’s membrane bound nucleus and organelles. With the genes bound in a nucleus, the eukaryotic cell must be able to transport its mRNA to the cytoplasm and must protect its mRNA from degrading before it is translated. Eukaryotes also employ three different polymerases that each transcribe a different subset of genes. Eukaryotic mRNAs are usually monogenic, meaning that they specify a single protein.

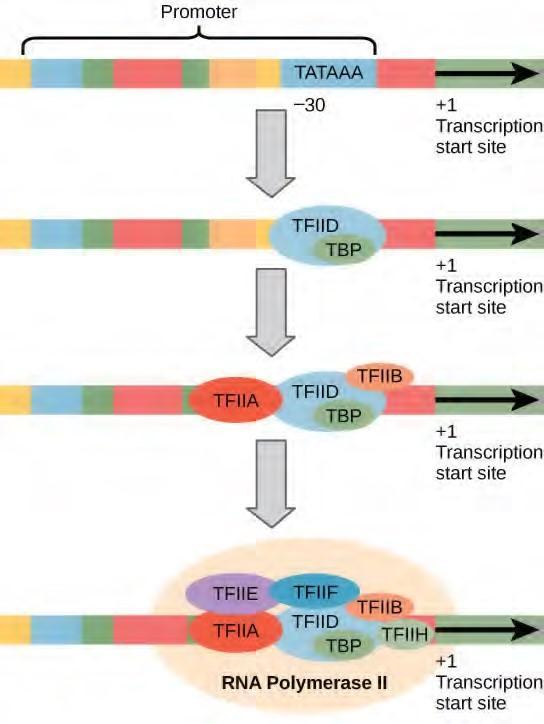

Initiation of Transcription in Eukaryotes

Unlike the prokaryotic polymerase that can bind to a DNA template on its own, eukaryotes require several other proteins, called transcription factors, to first bind to the promoter region and then help recruit the appropriate polymerase.

The Three Eukaryotic RNA Polymerases

The features of eukaryotic mRNA synthesis are markedly more complex those of prokaryotes. Instead of a single polymerase comprising five subunits, the eukaryotes have three polymerases that are each made up of 10 subunits or more. Each eukaryotic polymerase also requires a distinct set of transcription factors to bring it to the DNA template.

Figure 9.28 A generalized promoter of a gene transcribed by RNA polymerase II is shown. Transcription factors recognize the promoter. RNA polymerase II then binds and forms the transcription initiation complex.

Transcription Factors for RNA Polymerase II

The complexity of eukaryotic transcription does not end with the polymerases and promoters. An army of basal transcription factors, enhancers, and silencers also help to regulate the frequency with which pre-mRNA is synthesized from a gene. Enhancers and silencers affect the efficiency of transcription but are not necessary for transcription to proceed. Basal transcription factors are crucial in the formation of a preinitiation complex on the DNA template that subsequently recruits RNA polymerase II for transcription initiation.

The names of the basal transcription factors begin with “TFII” (this is the transcription factor for RNA polymerase II) and are specified with the letters A–J. The transcription factors systematically fall into place on the DNA template, with each one further stabilizing the preinitiation complex and contributing to the recruitment of RNA polymerase II.

The processes of bringing RNA polymerases I and III to the DNA template involve slightly less complex collections of transcription factors, but the general theme is the same. Eukaryotic transcription is a tightly regulated process that requires a variety of proteins to interact with each other and with the DNA strand. Although the process of transcription in eukaryotes involves a greater metabolic investment than in prokaryotes, it ensures that the cell transcribes precisely the pre-mRNAs that it needs for protein synthesis.

The Evolution of Promoters

The evolution of genes may be a familiar concept. Mutations can occur in genes during DNA replication, and the result may or may not be beneficial to the cell. By altering an enzyme, structural protein, or some other factor, the process of mutation can transform functions or physical features. However, eukaryotic promoters and other gene regulatory sequences may evolve as well. For instance, consider a gene that, over many generations, becomes more valuable to the cell. Maybe the gene encodes a structural protein that the cell needs to synthesize in abundance for a certain function. If this is the case, it would be beneficial to the cell for that gene’s promoter to recruit transcription factors more efficiently and increase gene expression. Scientists examining the evolution of promoter sequences have reported varying results. In part, this is because it is difficult to infer exactly where a eukaryotic promoter begins and ends. Some promoters occur within genes; others are located very far upstream, or even downstream, of the genes they are regulating. However, when researchers limited their examination to human core promoter sequences that were defined experimentally as sequences that bind the preinitiation complex, they found that promoters evolve even faster than protein-coding genes.

It is still unclear how promoter evolution might correspond to the evolution of humans or other higher organisms. However, the evolution of a promoter to effectively make more or less of a given gene product is an intriguing alternative to the evolution of the genes

1.H Liang et al., “Fast evolution of core promoters in primate genomes,” Molecular Biology and Evolution 25 (2008): 1239–44.

Eukaryotic Elongation and Termination

Following the formation of the preinitiation complex, the polymerase is released from the other transcription factors, and elongation is allowed to proceed as it does in prokaryotes with the polymerase synthesizing pre-mRNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction. As discussed previously, RNA polymerase II transcribes the major share of eukaryotic genes, so this section will focus on how this polymerase accomplishes elongation and termination.

Although the enzymatic process of elongation is essentially the same in eukaryotes and prokaryotes, the DNA template is more complex. When eukaryotic cells are not dividing, their genes exist as a diffuse mass of DNA and proteins called chromatin. The DNA is tightly packaged around charged histone proteins at repeated intervals. These DNA–histone complexes, collectively called nucleosomes, are regularly spaced and include 146 nucleotides of DNA wound around eight histones like thread around a spool.

For polynucleotide synthesis to occur, the transcription machinery needs to move histones out of the way every time it encounters a nucleosome. This is accomplished by a special protein complex called FACT, which stands for “facilitates chromatin transcription.” This complex pulls histones away from the DNA template as the polymerase moves along it. Once the pre-mRNA is synthesized, the FACT complex replaces the histones to recreate the nucleosomes.

The termination of transcription is different for the different polymerases. Unlike in prokaryotes, elongation by RNA polymerase II in eukaryotes takes place 1,000–2,000 nucleotides beyond the end of the gene being transcribed. This pre-mRNA tail is subsequently removed by cleavage during mRNA processing. On the other hand, RNA polymerases I and III require termination signals. Genes transcribed by RNA polymerase I contain a specific 18-nucleotide sequence that is recognized by a termination protein. The process of termination in RNA polymerase III involves an mRNA hairpin similar to rho independent termination of transcription in prokaryotes.

9.9 | RNA Processing in Eukaryotes

After transcription, eukaryotic pre-mRNAs must undergo several processing steps before they can be translated. Eukaryotic (and prokaryotic) tRNAs and rRNAs also undergo processing before they can function as components in the protein synthesis machinery.

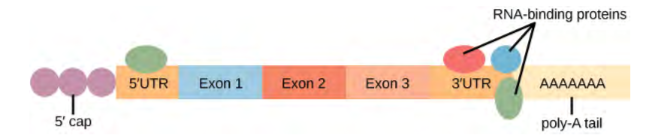

mRNA Processing

The eukaryotic pre-mRNA undergoes extensive processing before it is ready to be translated. The additional steps involved in eukaryotic mRNA maturation create a molecule with a much longer half-life than a prokaryotic mRNA. Eukaryotic mRNAs last for several hours, whereas the typical E. coli mRNA lasts no more than five seconds.

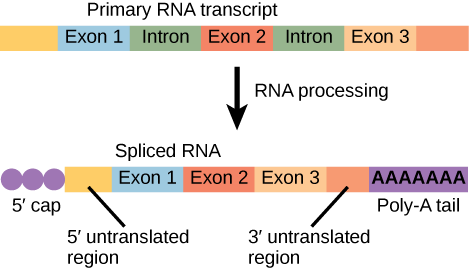

Pre-mRNAs are first coated in RNA-stabilizing proteins; these protect the pre-mRNA from degradation while it is processed and exported out of the nucleus. The three most important steps of pre-mRNA processing are the addition of stabilizing and signaling factors at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the molecule, and the removal of intervening sequences that do not specify the appropriate amino acids. In rare cases, the mRNA transcript can be “edited” after it is transcribed.

Pre-mRNA Splicing

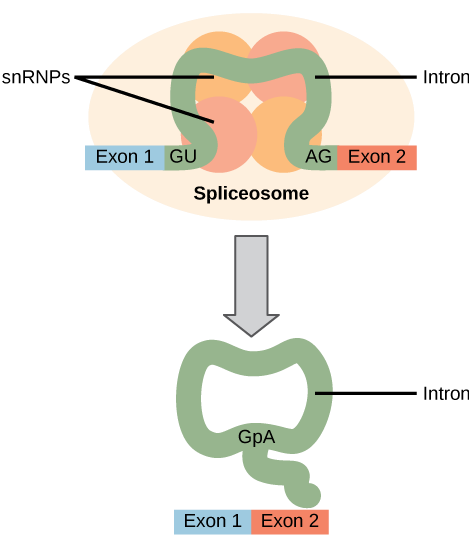

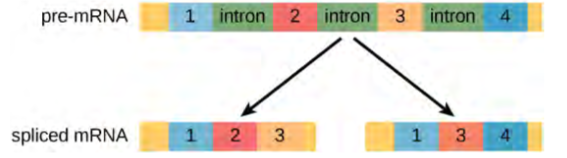

Eukaryotic genes are composed of exons, which correspond to protein-coding sequences (ex-on signifies that they are expressed), and intervening sequences called introns (int-ron denotes their intervening role), which may be involved in gene regulation but are removed from the pre-mRNA during processing. Intron sequences in mRNA do not encode functional proteins.

The discovery of introns came as a surprise to researchers in the 1970s who expected that pre-mRNAs would specify protein sequences without further processing, as they had observed in prokaryotes. The genes of higher eukaryotes very often contain one or more introns. These regions may correspond to regulatory sequences; however, the biological significance of having many introns or having very long introns in a gene is unclear. It is possible that introns slow down gene expression because it takes longer to transcribe pre-mRNAs with lots of introns. Alternatively, introns may be nonfunctional sequence remnants left over from the fusion of ancient genes throughout evolution. This is supported by the fact that separate exons often encode separate protein subunits or domains. For the most part, the sequences of introns can be mutated without ultimately affecting the protein product.

All of a pre-mRNA’s introns must be completely and precisely removed before protein synthesis. If the process errs by even a single nucleotide, the reading frame of the rejoined exons would shift, and the resulting protein would be dysfunctional. The process of removing introns and reconnecting exons is called splicing (Figure 15.13). Introns are removed and degraded while the pre-mRNA is still in the nucleus. Splicing occurs by a sequence-specific mechanism that ensures introns will be removed and exons rejoined with the accuracy and precision of a single nucleotide. The splicing of pre-mRNAs is conducted by complexes of proteins and RNA molecules called spliceosomes.

Note that more than 70 individual introns can be present, and each has to undergo the process of splicing—in addition to 5′ capping and the addition of a poly-A tail—just to generate a single, translatable mRNA molecule.

See how introns are removed during RNA splicing at this website (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ RNA_splicing) .

Processing of tRNAs and rRNAs

The tRNAs and rRNAs are structural molecules that have roles in protein synthesis; however, these RNAs are not themselves translated. Pre-rRNAs are transcribed, processed, and assembled into ribosomes in the nucleolus. Pre-tRNAs are transcribed and processed in the nucleus and then released into the cytoplasm where they are linked to free amino acids for protein synthesis.

Most of the tRNAs and rRNAs in eukaryotes and prokaryotes are first transcribed as a long precursor molecule that spans multiple rRNAs or tRNAs. Enzymes then cleave the precursors into subunits corresponding to each structural RNA. Some of the bases of pre-rRNAs are methylated; that is, a –CH3 moiety (methyl functional group) is added for stability. Pre-tRNA molecules also undergo methylation. As with pre-mRNAs, subunit excision occurs in eukaryotic pre-RNAs destined to become tRNAs or rRNAs.

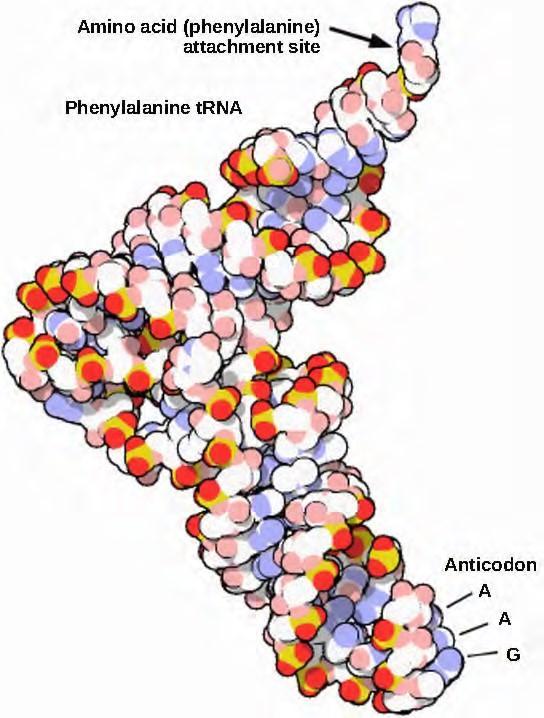

Mature rRNAs make up approximately 50 percent of each ribosome. Some of a ribosome’s RNA molecules are purely structural, whereas others have catalytic or binding activities. Mature tRNAs take on a three-dimensional structure through intramolecular hydrogen bonding to position the amino acid binding site at one end and the anticodon at the other end (Figure 15.14). The anticodon is a three nucleotide sequence in a tRNA that interacts with an mRNA codon through complementary base pairing.

Figure 9.29 This is a space-filling model of a tRNA molecule that adds the amino acid phenylalanine to a growing polypeptide chain. The anticodon AAG binds the Codon UUC on the mRNA. The amino acid phenylalanine is attached to the other end of the tRNA.

9.10 | Ribosomes and Protein Synthesis

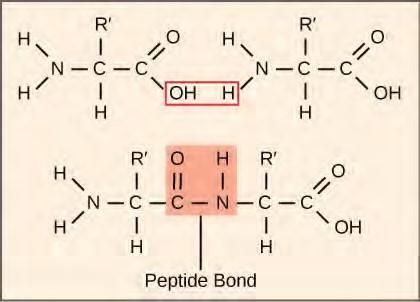

The synthesis of proteins consumes more of a cell’s energy than any other metabolic process. In turn, proteins account for more mass than any other component of living organisms (with the exception of water), and proteins perform virtually every function of a cell. The process of translation, or protein synthesis, involves the decoding of an mRNA message into a polypeptide product. Amino acids are covalently strung together by interlinking peptide bonds in lengths ranging from approximately 50 amino acid residues to more than 1,000. Each individual amino acid has an amino group (NH2) and a carboxyl (COOH) group. Polypeptides are formed when the amino group of one amino acid forms an amide (i.e., peptide) bond with the carboxyl group of another amino acid (Figure 9.30). This reaction is catalyzed by ribosomes and generates one water molecule.

Figure 9.30 A peptide bond links the carboxyl end of one amino acid with the amino end of another, expelling one water molecule. For simplicity in this image, only the functional groups involved in the peptide bond are shown. The R and R’ designations refer to the rest of each amino acid structure.

The Protein Synthesis Machinery

In addition to the mRNA template, many molecules and macromolecules contribute to the process of translation. The composition of each component may vary across species; for instance, ribosomes may consist of different numbers of rRNAs and polypeptides depending on the organism. However, the general structures and functions of the protein synthesis machinery are comparable from bacteria to human cells. Translation requires the input of an mRNA template, ribosomes, tRNAs, and various enzymatic factors.

Click through the steps of this PBS interactive (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/prokary_protein) to see protein synthesis in action.

Ribosomes

Even before an mRNA is translated, a cell must invest energy to build each of its ribosomes. In E. coli, there are between 10,000 and 70,000 ribosomes present in each cell at any given time. A ribosome is a complex macromolecule composed of structural and catalytic rRNAs, and many distinct polypeptides. In eukaryotes, the nucleolus is completely specialized for the synthesis and assembly of rRNAs.

Ribosomes exist in the cytoplasm in prokaryotes and in the cytoplasm and rough endoplasmic reticulum in eukaryotes. Mitochondria and chloroplasts also have their own ribosomes in the matrix and stroma, which look more similar to prokaryotic ribosomes (and have similar drug sensitivities) than the ribosomes just outside their outer membranes in the cytoplasm. Ribosomes dissociate into large and small subunits when they are not synthesizing proteins and reassociate during the initiation of translation. In E. coli, the small subunit is described as 30S, and the large subunit is 50S, for a total of 70S (recall that Svedberg units are not additive). Mammalian ribosomes have a small 40S subunit and a large 60S subunit, for a total of 80S. The small subunit is responsible for binding the mRNA template, whereas the large subunit sequentially binds tRNAs. Each mRNA molecule is simultaneously translated by many ribosomes, all synthesizing protein in the same direction: reading the mRNA from 5′ to 3′ and synthesizing the polypeptide from the N terminus to the C terminus. The complete mRNA/poly-ribosome structure is called a polysome.

tRNAs

The tRNAs are structural RNA molecules that were transcribed from genes by RNA polymerase III. Depending on the species, 40 to 60 types of tRNAs exist in the cytoplasm. Serving as adaptors, specific tRNAs bind to sequences on the mRNA template and add the corresponding amino acid to the polypeptide chain. Therefore, tRNAs are the molecules that actually “translate” the language of RNA into the language of proteins.

Of the 64 possible mRNA codons—or triplet combinations of A, U, G, and C—three specify the termination of protein synthesis and 61 specify the addition of amino acids to the polypeptide chain. Of these 61, one codon (AUG) also encodes the initiation of translation. Each tRNA anticodon can base pair with one of the mRNA codons and add an amino acid or terminate translation, according to the genetic code. For instance, if the sequence CUA occurred on an mRNA template in the proper reading frame, it would bind a tRNA expressing the complementary sequence, GAU, which would be linked to the amino acid leucine.

As the adaptor molecules of translation, it is surprising that tRNAs can fit so much specificity into such a small package. Consider that tRNAs need to interact with three factors: 1) they must be recognized by the correct aminoacyl synthetase (see below); 2) they must be recognized by ribosomes; and 3) they must bind to the correct sequence in mRNA.

Aminoacyl tRNA Synthetases

The process of pre-tRNA synthesis by RNA polymerase III only creates the RNA portion of the adaptor molecule. The corresponding amino acid must be added later, once the tRNA is processed and exported to the cytoplasm. Through the process of tRNA “charging,” each tRNA molecule is linked to its correct amino acid by a group of enzymes called aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. At least one type of aminoacyl tRNA synthetase exists for each of the 20 amino acids; the exact number of aminoacyl tRNA synthetases varies by species. These enzymes first bind and hydrolyze ATP to catalyze a high-energy bond between an amino acid and adenosine monophosphate (AMP); a pyrophosphate molecule is expelled in this reaction. The activated amino acid is then transferred to the tRNA, and AMP is released.

The Mechanism of Protein Synthesis

As with mRNA synthesis, protein synthesis can be divided into three phases: initiation, elongation, and termination. The process of translation is similar in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Here we’ll explore how translation occurs in E. coli, a representative prokaryote, and specify any differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic translation.

Initiation of Translation

Protein synthesis begins with the formation of an initiation complex. In E. coli, this complex involves the small 30S ribosome, the mRNA template, three initiation factors (IFs; IF-1, IF-2, and IF-3), and a special initiator tRNA, called tRNAMetf . The initiator tRNA interacts with the start codon AUG (or rarely, GUG), links to a formylated methionine called fMet, and can also bind IF-2. Formylated methionine is inserted by fMet − tRNAMef t at the beginning of every polypeptide chain synthesized by E. coli, but it is usually clipped off after translation is complete. When an in-frame AUG is encountered during translation elongation, a non-formylated methionine is inserted by a regular Met-tRNAMet.

In E. coli mRNA, a sequence upstream of the first AUG codon, called the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AGGAGG), interacts with the rRNA molecules that compose the ribosome. This interaction anchors the 30S ribosomal subunit at the correct location on the mRNA template. Guanosine triphosphate (GTP), which is a purine nucleotide triphosphate, acts as an energy source during translation—both at the start of elongation and during the ribosome’s translocation.

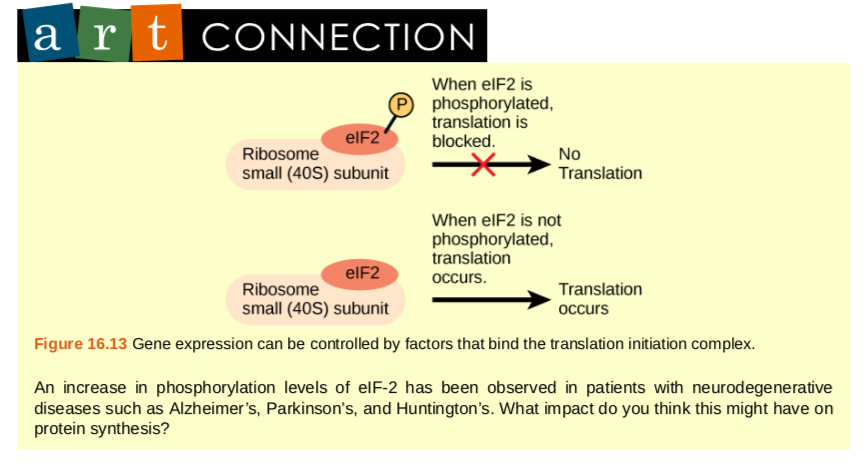

In eukaryotes, a similar initiation complex forms, comprising mRNA, the 40S small ribosomal subunit, IFs, and nucleoside triphosphates (GTP and ATP). The charged initiator tRNA, called Met-tRNAi, does not bind fMet in eukaryotes, but is distinct from other Met-tRNAs in that it can bind IFs.

Instead of depositing at the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, the eukaryotic initiation complex recognizes the

7-methylguanosine cap at the 5′ end of the mRNA. A cap-binding protein (CBP) and several other IFs assist the movement of the ribosome to the 5′ cap. Once at the cap, the initiation complex tracks along the mRNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction, searching for the AUG start codon. Many eukaryotic mRNAs are translated from the first AUG, but this is not always the case. According to Kozak’s rules, the nucleotides around the AUG indicate whether it is the correct start codon. Kozak’s rules state that the following consensus sequence must appear around the AUG of vertebrate genes: 5′-gccRccAUGG-3′. The R (for purine) indicates a site that can be either A or G, but cannot be C or U. Essentially, the closer the sequence is to this consensus, the higher the efficiency of translation.

Once the appropriate AUG is identified, the other proteins and CBP dissociate, and the 60S subunit binds to the complex of Met-tRNAi, mRNA, and the 40S subunit. This step completes the initiation of translation in eukaryotes.

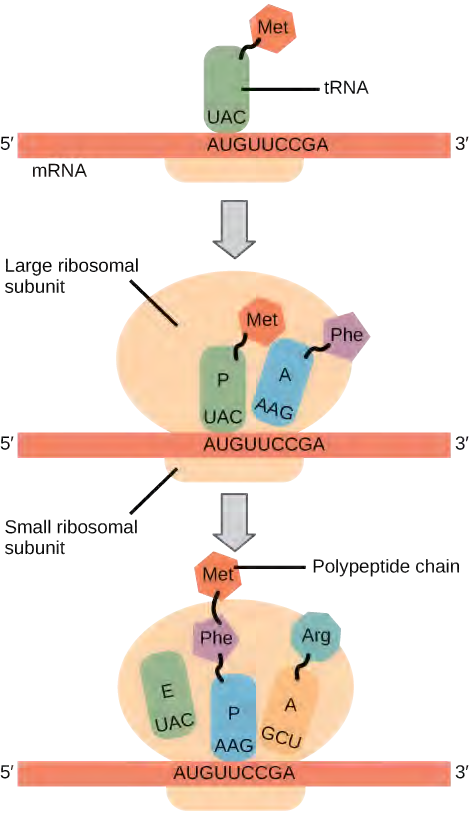

Translation, Elongation, and Termination

In prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the basics of elongation are the same, so we will review elongation from the perspective of E. coli. The 50S ribosomal subunit of E. coli consists of three compartments: the A (aminoacyl) site binds incoming charged aminoacyl tRNAs. The P (peptidyl) site binds charged tRNAs carrying amino acids that have formed peptide bonds with the growing polypeptide chain but have not yet dissociated from their corresponding tRNA. The E (exit) site releases dissociated tRNAs so that they can be recharged with free amino acids. There is one exception to this assembly line of tRNAs: in E. coli, fMet − tRNAMetf is capable of entering the P site directly without first entering the A site. Similarly, the eukaryotic Met-tRNAi, with help from other proteins of the initiation complex, binds directly to the P site. In both cases, this creates an initiation complex with a free A site ready to accept the tRNA corresponding to the first codon after the AUG.

During translation elongation, the mRNA template provides specificity. As the ribosome moves along the mRNA, each mRNA codon comes into register, and specific binding with the corresponding charged tRNA anticodon is ensured. If mRNA were not present in the elongation complex, the ribosome would bind tRNAs nonspecifically.

Elongation proceeds with charged tRNAs entering the A site and then shifting to the P site followed by the E site with each single-codon “step” of the ribosome. Ribosomal steps are induced by conformational changes that advance the ribosome by three bases in the 3′ direction. The energy for each step of the ribosome is donated by an elongation factor that hydrolyzes GTP. Peptide bonds form between the amino group of the amino acid attached to the A-site tRNA and the carboxyl group of the amino acid attached to the P-site tRNA. The formation of each peptide bond is catalyzed by peptidyl transferase, an RNA-based enzyme that is integrated into the 50S ribosomal subunit. The energy for each peptide bond formation is derived from GTP hydrolysis, which is catalyzed by a separate elongation factor. The amino acid bound to the P-site tRNA is also linked to the growing polypeptide chain. As the ribosome steps across the mRNA, the former P-site tRNA enters the E site, detaches from the amino acid, and is expelled (Figure 14.31). Amazingly, the E. coli translation apparatus takes only 0.05 seconds to add each amino acid, meaning that a 200-amino acid protein can be translated in just 10 seconds.

Termination of translation occurs when a nonsense codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) is encountered. Upon aligning with the A site, these nonsense codons are recognized by release factors in prokaryotes and eukaryotes that instruct peptidyl transferase to add a water molecule to the carboxyl end of the P-site amino acid. This reaction forces the P-site amino acid to detach from its tRNA, and the newly made protein is released. The small and large ribosomal subunits dissociate from the mRNA and from each other; they are recruited almost immediately into another translation initiation complex. After many ribosomes have completed translation, the mRNA is degraded so the nucleotides can be reused in another transcription reaction.

Protein Folding, Modification, and Targeting

During and after translation, individual amino acids may be chemically modified, signal sequences may be appended, and the new protein “folds” into a distinct three-dimensional structure as a result of intramolecular interactions. A signal sequence is a short tail of amino acids that directs a protein to a specific cellular compartment. These sequences at the amino end or the carboxyl end of the protein can be thought of as the protein’s “train ticket” to its ultimate destination. Other cellular factors recognize each signal sequence and help transport the protein from the cytoplasm to its correct compartment. For instance, a specific sequence at the amino terminus will direct a protein to the mitochondria or chloroplasts (in plants). Once the protein reaches its cellular destination, the signal sequence is usually clipped off.

Many proteins fold spontaneously, but some proteins require helper molecules, called chaperones, to prevent them from aggregating during the complicated process of folding. Even if a protein is properly specified by its corresponding mRNA, it could take on a completely dysfunctional shape if abnormal temperature or pH conditions prevent it from folding correctly.

9.11 | Regulation of Gene Expression

For a cell to function properly, necessary proteins must be synthesized at the proper time. All cells control or regulate the synthesis of proteins from information encoded in their DNA. The process of turning on a gene to produce RNA and protein is called gene expression. Whether in a simple unicellular organism or a complex multi-cellular organism, each cell controls when and how its genes are expressed. For this to occur, there must be a mechanism to control when a gene is expressed to make RNA and protein, how much of the protein is made, and when it is time to stop making that protein because it is no longer needed.

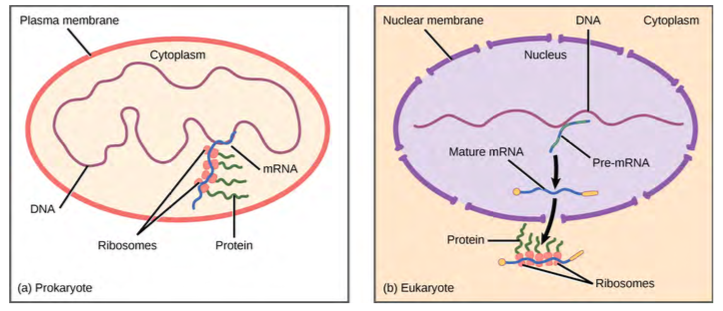

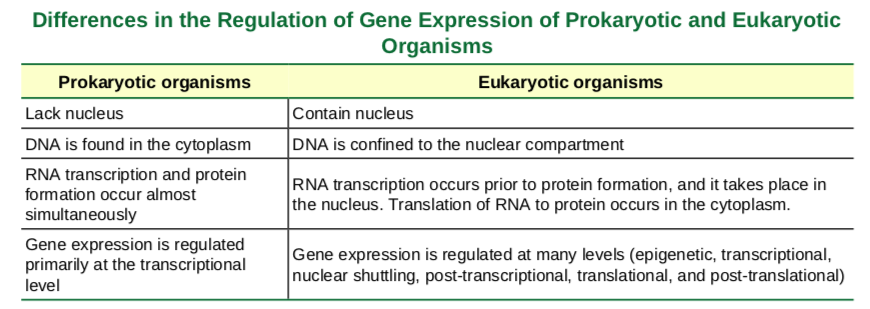

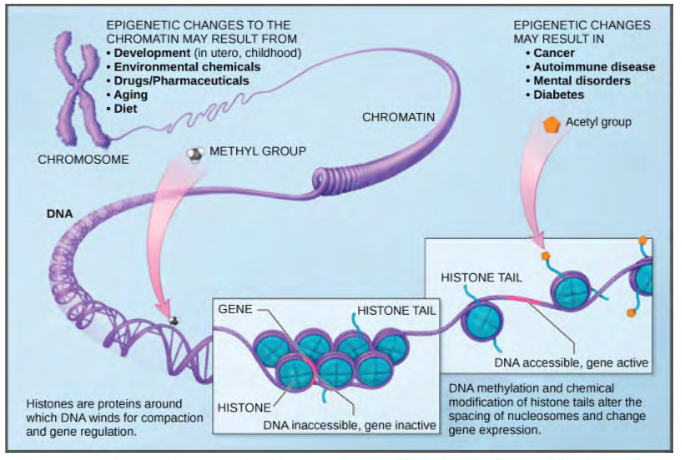

Prokaryotic versus Eukaryotic Gene Expression

To understand how gene expression is regulated, we must first understand how a gene codes for a functional protein in a cell. The process occurs in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, just in slightly different manners.Prokaryotic organisms are single-celled organisms that lack a cell nucleus, and their DNA therefore floats freely in the cell cytoplasm. To synthesize a protein, the processes of transcription and translation occur almost simultaneously. When the resulting protein is no longer needed, transcription stops. As a result, the primary method to control what type of protein and how much of each protein is expressed in a prokaryotic cell is the regulation of DNA transcription. All of the subsequent steps occur automatically. When more protein is required, more transcription occurs. Therefore, in prokaryotic cells, the control of gene expression is mostly at the transcriptional level.Eukaryotic cells, in contrast, have intracellular organelles that add to their complexity. In eukaryotic cells, the DNA is contained inside the cell’s nucleus and there it is transcribed into RNA. The newly synthesized RNA is then transported out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where ribosomes translate the RNA into protein. The processes of transcription and translation are physically separated by the nuclear membrane; transcription occurs only within the nucleus, and translation occurs only outside the nucleus in the cytoplasm. The regulation of gene expression can occur at all stages of the process (Figure 16.2). Regulation may occur when the DNA is uncoiled and loosened from nucleosomes to bind transcription factors ( epigenetic level), when the RNA is transcribed (transcriptional level), when the RNA is processed and exported to the cytoplasm after it is transcribed ( post-transcriptional level), when the RNA is translated into protein (translational level), or after the protein has been made ( post-translational level).

Figure 9.32 Prokaryotic transcription and translation occur simultaneously in the cytoplasm, and regulation occurs at the transcriptional level. Eukaryotic gene expression is regulated during transcription and RNA processing, which take place in the nucleus, and during protein translation, which takes place in the cytoplasm. Further regulation may occur through post-translational modifications of proteins.

9.12 | Prokaryotic Gene Regulation

The DNA of prokaryotes is organized into a circular chromosome supercoiled in the nucleoid region of the cell cytoplasm. Proteins that are needed for a specific function, or that are involved in the same biochemical pathway, are encoded together in blocks called operons. For example, all of the genes needed to use lactose as an energy source are coded next to each other in the lactose (or lac) operon.

In prokaryotic cells, there are three types of regulatory molecules that can affect the expression of operons: repressors, activators, and inducers. Repressors are proteins that suppress transcription of a gene in response to an external stimulus, whereas activators are proteins that increase the transcription of a gene in response to an external stimulus. Finally, inducers are small molecules that either activate or repress transcription depending on the needs of the cell and the availability of substrate.

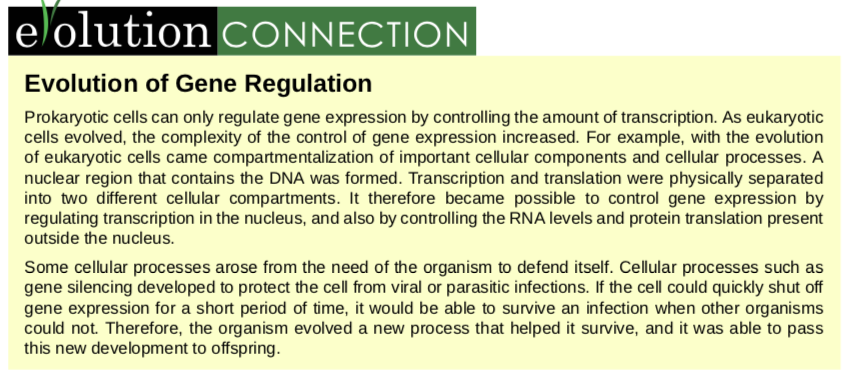

The trp Operon: A Repressor Operon

Bacteria such as E. coli need amino acids to survive. Tryptophan is one such amino acid that E. coli can ingest from the environment. E. coli can also synthesize tryptophan using enzymes that are encoded by five genes. These five genes are next to each other in what is called the tryptophan (trp) operon (Figure 9.33). If tryptophan is present in the environment, then E. coli does not need to synthesize it and the switch controlling the activation of the genes in the trp operon is switched off. However, when tryptophan availability is low, the switch controlling the operon is turned on, transcription is initiated, the genes are expressed, and tryptophan is synthesized.

Figure 9.33 The five genes that are needed to synthesize tryptophan in E. coli are located next to each other in the trp operon. When tryptophan is plentiful, two tryptophan molecules bind the repressor protein at the operator sequence. This physically blocks the RNA polymerase from transcribing the tryptophan genes. When tryptophan is absent, the repressor protein does not bind to the operator and the genes are transcribed.A DNA sequence that codes for proteins is referred to as the coding region. The five coding regions for the tryptophan biosynthesis enzymes are arranged sequentially on the chromosome in the operon. Just before the coding region is the transcriptional start site. This is the region of DNA to which RNA polymerase binds to initiate transcription. The promoter sequence is upstream of the transcriptional start site; each operon has a sequence within or near the promoter to which proteins (activators or repressors) can bind and regulate transcription.

Watch this video (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/trp_operon) to learn more about the trp operon.

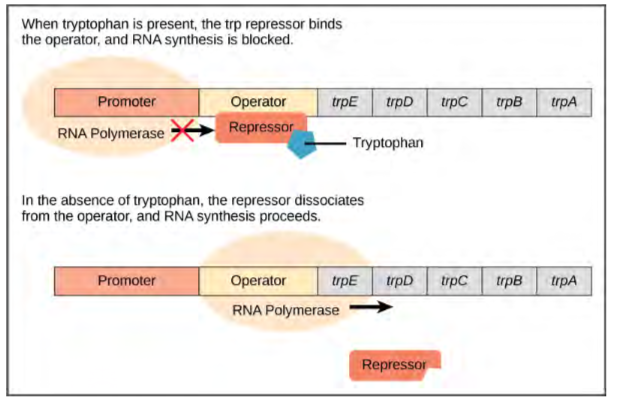

Catabolite Activator Protein (CAP): An Activator Regulator

Just as the trp operon is negatively regulated by tryptophan molecules, there are proteins that bind to the operator sequences that act as a positive regulator to turn genes on and activate them. For example, when glucose is scarce, E. coli bacteria can turn to other sugar sources for fuel. To do this, new genes to process these alternate genes must be transcribed. When glucose levels drop, cyclic AMP (cAMP) begins to accumulate in the cell. The cAMP molecule is a signaling molecule that is involved in glucose and energy metabolism in E. coli. When glucose levels decline in the cell, accumulating cAMP binds to the positive regulator catabolite activator protein (CAP), a protein that binds to the promoters of operons that control the processing of alternative sugars. When cAMP binds to CAP, the complex binds to the promoter region of the genes that are needed to use the alternate sugar sources (Figure 16.4). In these operons, a CAP binding site is located upstream of the RNA polymerase binding site in the promoter. This increases the binding ability of RNA polymerase to the promoter region and the transcription of the genes.

Figure 9.34 When glucose levels fall, E. coli may use other sugars for fuel but must transcribe new genes to do so. As glucose supplies become limited, cAMP levels increase. This cAMP binds to the CAP protein, a positive regulator that binds to an operator region upstream of the genes required to use other sugar sources.

The lac Operon: An Inducer Operon

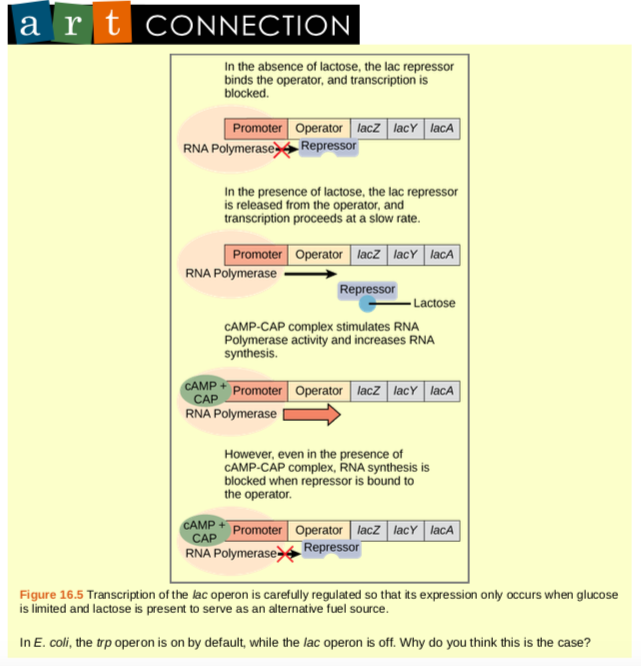

The third type of gene regulation in prokaryotic cells occurs through inducible operons, which have proteins that bind to activate or repress transcription depending on the local environment and the needs of the cell. The lac operon is a typical inducible operon. As mentioned previously, E. coli is able to use other sugars as energy sources when glucose concentrations are low. To do so, the cAMP–CAP protein complex serves as a positive regulator to induce transcription. One such sugar source is lactose. The lac operon encodes the genes necessary to acquire and process the lactose from the local environment. CAP binds to the operator sequence upstream of the promoter that initiates transcription of the lac operon. However, for the lac operon to be activated, two conditions must be met. First, the level of glucose must be very low or non-existent. Second, lactose must be present. Only when glucose is absent and lactose is present will the lac operon be transcribed (Figure 16.5). This makes sense for the cell, because it would be energetically wasteful to create the proteins to process lactose if glucose was plentiful or lactose was not available.

If glucose is absent, then CAP can bind to the operator sequence to activate transcription. If lactose is absent, then the repressor binds to the operator to prevent transcription. If either of these requirements is met, then transcription remains off. Only when both conditions are satisfied is the lac operon transcribed (Table 16.2).

Watch an animated tutorial (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/lac_operon) about the workings of lac operon here.

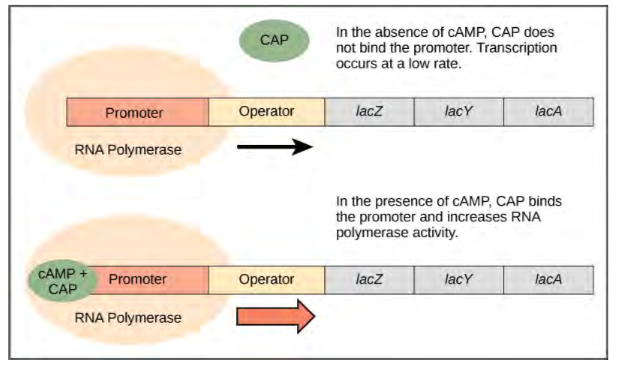

9.13 | Eukaryotic Epigenetic Gene Regulation

Eukaryotic gene expression is more complex than prokaryotic gene expression because the processes of transcription and translation are physically separated. Unlike prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells can regulate gene expression at many different levels. Eukaryotic gene expression begins with control of access to the DNA. This form of regulation, called epigenetic regulation, occurs even before transcription is initiated.

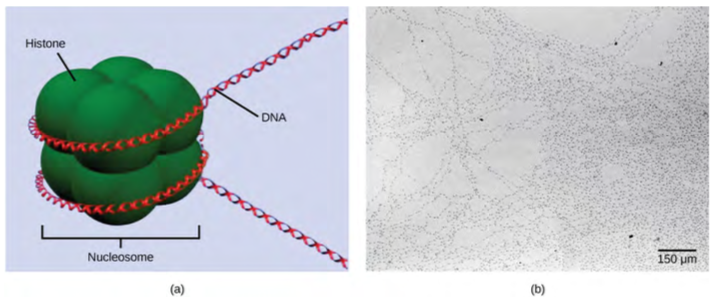

The first level of organization, or packing, is the winding of DNA strands around histone proteins. Histones package and order DNA into structural units called nucleosome complexes, which can control the access of proteins to the DNA regions (Figure 16.6a). Under the electron microscope, this winding of DNA around histone proteins to form nucleosomes looks like small beads on a string (Figure 16.6b). These beads (histone proteins) can move along the string (DNA) and change the structure of the molecule.

Figure 9.35 DNA is folded around histone proteins to create (a) nucleosome complexes. These nucleosomes control the access of proteins to the underlying DNA. When viewed through an electron microscope (b), the nucleosomes look like beads on a string. (credit “micrograph”: modification of work by Chris Woodcock)

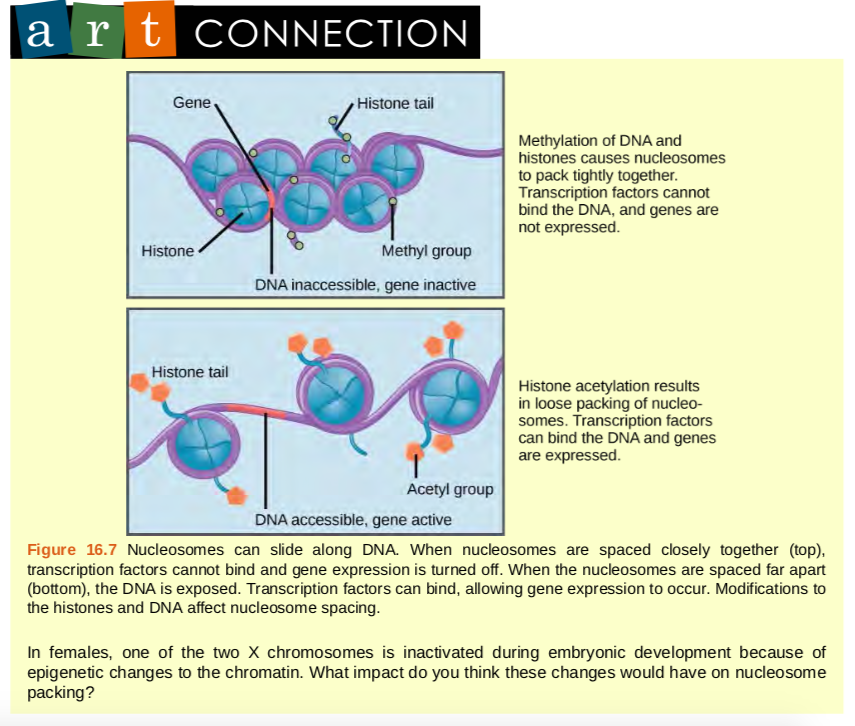

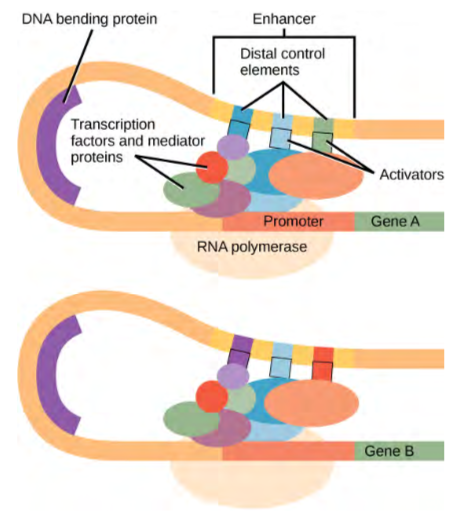

If DNA encoding a specific gene is to be transcribed into RNA, the nucleosomes surrounding that region of DNA can slide down the DNA to open that specific chromosomal region and allow for the transcriptional machinery (RNA polymerase) to initiate transcription (Figure 9.35). Nucleosomes can move to open the chromosome structure to expose a segment of DNA, but do so in a very controlled manner.

Figure 9.36 Nucleosomes can slide along DNA. When nucleosomes are spaced closely together (top), transcription factors cannot bind and gene expression is turned off. When the nucleosomes are spaced far apart (bottom), the DNA is exposed. Transcription factors can bind, allowing gene expression to occur. Modifications to the histones and DNA affect nucleosome spacing.

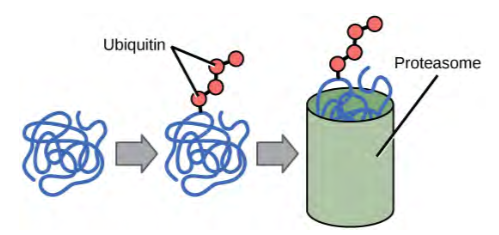

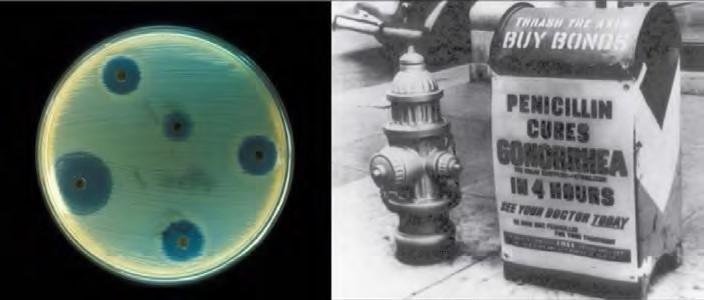

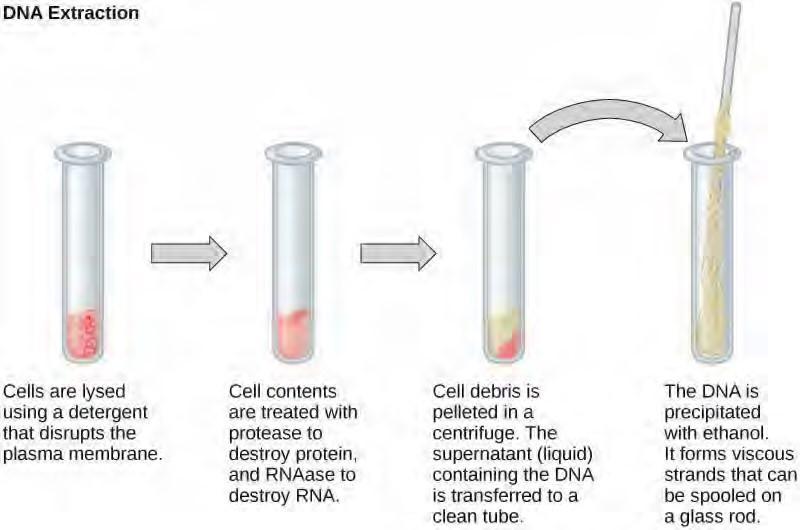

In females, one of the two X chromosomes is inactivated during embryonic development because of epigenetic changes to the chromatin. What impact do you think these changes would have on nucleosome packing?