Chapter 9: Critical Reading and Reflection

“Reflection is a systematic, rigorous, disciplined way of thinking.”

–Carol Rogers (1)

Political scientists share with other social scientists—indeed, with all well-educated people—a talent for critical reading. Doing so requires a great deal of practice. Critical reading involves developing certain intellectual and behavioral habits. If you apply a systematic approach to reading texts, you will achieve deeper understanding than if you just read superficially. The critical reading guidelines below constitute a blend of the advice offered by Salisbury University, the University of Minnesota, Harvard University, and Empire State College. You should use these guidelines in this course and in other situations where you encounter texts. Texts might be articles, primary source documents, speeches, etc.—in which the author attempts to explain a political situation, to convince the audience to reach a conclusion, or to take a specific action.

What Should You Do When You Encounter a Text?

Set the Context—It is important for you to be clear about the key components of a rhetorical context: An author puts forth a text—a form of communication with a specific purpose in mind that can be written or verbal—to an audience. For any text, you should be able to answer these questions:

- Who is the author?

- What is the author’s purpose? Who is the primary, secondary, and tertiary audience?

- How does the audience shape the author’s messaging and word choice?

- What is the occasion or situation for the communication?

- What qualifies the author to speak or write on the topic?

- From what political perspective does the author approach the topic? What is the context in which the author writes? What has happened in the past—and what has been happening recently—with respect to the topic?

- Why is the author communicating now, in this manner? What is the author hoping will happen as a result of his communication? Who benefits if their perspective is widely adopted?

Can you answer all these questions just by looking at the text itself? Probably not. You will need to research the author’s background and the topic to answer them.

Annotate—There are certain notes you should make as you read the text. If you have a hard copy, you can make annotations directly on the page. Follow a standard form of annotation, or come up with your own short-hand notation: an asterisk (*) in the margin might indicate the author’s thesis; a check mark (√) might indicate an effective phrase; a question mark (?) might mean a word or phrase you don’t understand, etc. It is often helpful to make a few written notes in the margin to remind yourself later what exactly you wanted to remember about that section. Otherwise, you can read the text online and make notations on a separate form or piece of paper. After reading the text a few times, you should highlight the following:

The text’s thesis or main point. The text’s title will hint at the thesis or main point, but that is not always the case. Sometimes, the thesis or main point is encapsulated in one sentence early in the piece, and sometimes it is more difficult to identify because its full expression might come later. In some cases, it might be spread out over several sentences that are not connected.

The evidence and/or reasoning that support the thesis or main point. This is easy enough to identify in short texts like opinion pieces or blog posts, as the support tends to stand out prominently. Often in longer texts, the evidence is a bit overwhelming. One good strategy is to highlight individual sentences that contain the most effective supporting evidence or reasoning.

Particularly powerful or illustrative phrases. Note when the author says or writes something that resonates with you or that you imagine must resonate with their primary audience. Note also phrases that illustrate a particular style or rhetorical appeal (see appeals below).

Words and phrases that you don’t understand. Authors often use words or phrases with which readers are not familiar. Circle them or rewrite them on a separate page and find out what they mean. Sometimes, learning these new words will expand your vocabulary to include words that educated people use, but sometimes—particularly with primary source documents—it means learning a phrase or specialized lingo that was popular during a given historical period or that refers to a certain subculture to which the author belongs.

Outline and Summarize—This is an interesting challenge. In your own words, boil down the text into one paragraph. Alternatively, distill the text into an outline that fits on one page. You should be able to perform one of these tasks with any text. Doing so helps you develop an overall picture of the author’s purpose.

Describe the Text’s Rhetorical Appeals—Either consciously or unconsciously, authors employ the rhetorical appeals ethos, logos, pathos, and kairos in the text. These appeals help the audience understand the author’s perspective. Note that texts often use multiple appeals. As you read a text, try to identify sentences or sections—or even the text’s whole character—that might apply to one of the following appeals:

- Ethos—This rhetorical appeal centers around the author’s credibility or trustworthiness. Such credibility—or lack thereof—can be vested inside the words the author uses; this is called intrinsic ethos and refers to the author’s character and integrity. You’ve all met or seen people who enjoy credibility with their audiences because they speak with a sophisticated vocabulary and fluency. The same goes for written arguments. Extrinsic ethos refers to credibility that resides outside the author’s text, and usually centers around the author’s credentials, reputation, or history with the subject, but can also depend on the author’s vested interest in the subject. For example, if a climatologist comes from a knowledgeable scientific community in which peers review each other’s work for appropriate methodology and evidentiary support, this scientist has considerably more extrinsic ethos than does someone who doesn’t write for peer-reviewed publications and/or who is being paid by the fossil fuel industry to create arguments favoring that industry.

- Logos—The appeal to logos has to do with the logic, evidence, or factual data that is used to persuade the audience. The first thing to look for here is whether the author is using fallacious arguments. Are they employing the straw man fallacy to make her point? Are they engaged in an ad hominem attack? After examining the text’s logic, the next thing you should do is look at the overall relationship between the author’s thesis/argument and the evidence they are using to support that point. Does the evidence support the thesis, or is the evidence tangential material that doesn’t really lead one to the conclusion the author would like you to reach? Finally, check the evidence itself. Is it actually evidence or just an unsubstantiated assertion? Does the evidence come from a credible source? Is the author excluding obvious contradictory evidence?

- Pathos—The English Department at the University of Missouri—Kansas City refers to pathos as the author’s appeal to the “audience’s sense of identity, their self-interest, and their emotions.” Speakers and writers employ many techniques to create a bond with their readers. For example, authors may refer to “everyman” tropes about working hard, providing for one’s children, going to church, and so on. They also appeal to their audience’s self-interest. For example, an author might tell an audience that they should care about the environmental destruction because it is the world in which their children or grandchildren must live. Appeals to pathos are most commonly thought of as appeals to emotion. Authors can stir up fear or patriotism or hope or any emotion to bring the audience around to their perspective. Be on the lookout for ways in which authors attempt to appeal to their audience’s sense of identity, their self-interest, or their emotions.

- Kairos–The Writing Commons describes kairos as “taking advantage of or even creating a perfect moment to deliver a particular message,” in the sense of “saying (or writing) the right thing at the right time.” For example, addressing disaster preparedness at an annual meeting of the city council is a different situation than addressing the same topic to a crowd of angry, cold, wet, and recently homeless people who have just survived the failure of an old dam that the local city council failed to fix. If I’m rhetorically sophisticated, I will tailor my language and tone to best match the differing audiences and circumstances. I also have an ethical responsibility to my audience and the situation. I can, for example, achieve my aims by manipulating or deceiving or preying upon people’s irrational fears, but this is at the expense of ever objectively and appropriately reaching kairos. As you encounter a text, examine the author’s modality and language. Does it fit or not fit the given situation? Is the author treating their audience fairly?

Reflect—If you’ve read through a text several times to annotate it and understand its rhetorical appeals, and if you’ve done some background research to establish its context, you’re now in a good place to reflect upon it. Examine your own thinking as you consider the piece.

- Did it challenge your assumptions or expand your understanding?

- Has your thinking been stretched by encountering this text?

- How does the text connect to other things you’ve read, to the broader world, or to your own situation?

- How would you describe the piece’s impact in a way that would excite other people to experience it as well?

Write about any or all of those things—and for goodness sake, don’t be afraid to be vulnerable or to elaborate!

Reflective Writing

Reflective writing is different than academic writing. Let me illustrate and be a little vulnerable myself by sharing two reflections that I wrote when I led a London study abroad trip. I completed the same broad assignment that I gave to students, which was to create a reflective ePortfolio that documented the political, historical, and cultural venues we visited. One ePortfolio assignment was dedicated to artwork that the students found particularly impactful. I advised students to choose their own art topic on which to reflect and urged them to think of each art piece as a text.

Here are two examples of reflection from my ePortfolio. I’ve annotated my responses [in blue brackets] to call attention to what I’m doing. Note how I answer some of my own questions from the previous paragraph.

Richard Long is a living British artist (b. 1945) whose work has been exhibited in galleries and museums around the world. This particular piece—a large set of five concentric circles made of small white stones, arranged on the concrete floor of the Tate Modern Art Museum—doesn’t really do justice to his other work (more about that later) and gives rise to a common reaction to modern art: “My kid could do that!” [Note that I’m setting the context here—where I am, what I’m looking at, and my initial reaction.]

Pretentious. Facile. Ridiculous. Those were some of the adjectives that went through my head when I first saw what looked like a target made of pebbles. “Come on,” I said aloud. “That’s not art.” According to Long, his work is “a balance between patterns of nature and the formalism of human abstract ideas, like lines and circles.” When I read this explanation on the information plaque, I tried to change my point of view to understand the piece as it might have been intended. When I shifted my perspective, it occurred to me that the piece might represent a stylized set of waves—as though a single white pebble had been dropped into a pool of liquid concrete. From that perspective, it looked like the industrialization of ripples in a mountain pond. [This paragraph shows how my assumptions were challenged by Long’s piece.]

The evening after our visit to the Tate Modern, I googled Richard Long and looked at his official site. I found that, in my opinion, his best work consists of natural installations set out in the wilderness. Check out this piece in Scotland, or this one in the mountains of California, or this one in India. “That’s more like it. These kinds of installations really appeal to me,” I thought. What do I see when I look at them? I see mankind’s primordial markings on the natural landscape. At some point in our evolution, we began to make lasting marks on the earth, tentative at first, but more substantial with time—such as the mysterious monument at Stonehenge that we visited. Eventually, our marks became highways, buildings, canals, and even alterations to the world’s atmospheric chemistry. Long’s works strike me as an attempt to visualize the beginnings of this tragic transformation from man-in-nature to man-apart-from-nature. At least, that’s what I take away from them, whether he intended so or not. These works, more than the piece I saw in the Tate Modern, speak to me. They are like warning beacons come too late. [I’m making connections here—first to other pieces by Long, and then to the larger issue of mankind’s impact of on the natural world. I’m coming to a new understanding that’s different and more sophisticated than my initial gut reaction to Long’s work.]

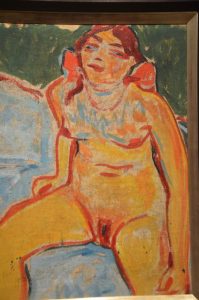

What’s the difference between art and pornography? That’s the question that flashed through my mind when I saw Seated Nude by Erich Heckel in the Courtauld Gallery. Is “acceptable nudity” considered art while “unacceptable nudity” is just porn? According to the information plaque at the Courtauld, Heckel’s portrait of a nude adolescent girl “was a deliberate attack on the moral and artistic taboos” of his era. I can certainly imagine that the painting was absolutely scandalous in 1909. Even today, most Americans would dismiss it as perverted and without merit. If Heckel’s intent was to use the painting as a social critique on the holdovers of Victorian morality, that political bent to the piece would clearly put it outside the Supreme Court’s definition of “obscenity.” But is that enough to justify the painting’s place in a prestigious London art museum? Surely, the painting signifies the kind of objectification that one associates with prurience. [Again, I’ve set the context—where I am, what I’m looking at—and I lead off with a question to the reader and to myself.]

The painting doesn’t strike me as intentionally sexual per se, but the girl’s pose— isolated on a bed, facing the viewer with her legs parted—looks like exploitative kiddie porn. In fact, I got a little self-conscious just as I was snapping a picture of the painting, wondering if other people in the room were glancing at the perv with the camera. Then, instead of continuing to look at the painting itself, I parked myself across the room and watched people as they approached the piece. As a rule, men gave it a side glance and moved on quickly, probably trying to not be seen as too interested in the painting. Women tended to look at it more intently. Maybe they were asking themselves the same art/porn question that had gone through my mind. [Deeper reflection and analysis here. I’m thinking about my thinking and asking whether I am the only one who is troubled by the piece.]

The painting’s ability to make people uncomfortable 100 years after it was created strikes me as a testament to the piece’s ability to challenge our puritanical impulses. It’s as though Heckel is saying, “Get over it, already!” He’s placing the burden of our discomfort squarely on our own shoulders, because the girl is going to continue gazing back at us whether we are blushing or not. [I’m challenging my initial assumption: Maybe the piece isn’t about the girl in the painting, but about the viewers.]

References

- Carol Rogers, “Defining Reflection: Another Look at John Dewey and Reflective Thinking,” Teachers College Record, 104(4). Page 845.

Media Attributions

- Small White Pebble Circle © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Seated Nude © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license