Chapter 50: Early Election Reforms

“The fact is that registration was created to stop black people and American citizen immigrants from voting. That is the real history of registration in the United States.”

—Greg Palast (1)

The election system that we have today was greatly shaped by three reforms pushed through at the state level in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth century. Because these are state laws, differences exist from one state to another, but we can make some generalizations.

The Australian Ballot

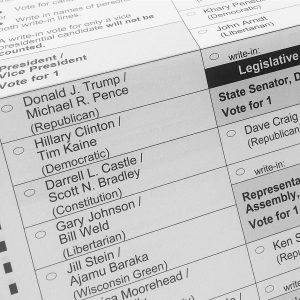

Introduced in Australia in 1855, the Australian ballot was the first reform that all U.S. states adopted by 1888. The Australian ballot has three important characteristics. 1) It is printed, distributed, and counted by the state at taxpayer expense. 2) It lists all the candidates for all the offices from all parties. 3) voters complete the ballot in private. While these characteristics of Australian ballots seem rather mundane today, they greatly changed the character of voting in the United States. Prior to the Australian ballot, the most common way to vote in the United States was to use party ballots, which were printed by the parties themselves. Upon arriving at the voting place, you were confronted by a literal party—bands playing, dancing, free food, and free booze. When you were ready to vote, you would pick up a ballot that only listed one party’s nominees for all the offices and drop it into the ballot box. The party ballots were color-coded, so it was very easy for your neighbors to see which party you supported. In addition, it was much easier to stuff the ballot box at the end of the day with the appropriate colored ballots—and no one would know the difference between a legitimate vote and a fraudulent one. (2) Finally, split-ticket voting was very difficult before the Australian ballot came along. Split-ticket voting is when you divide your votes among different parties for different offices. You might vote Democratic for president and Republican for representative. The prevalence of split-ticket voting peaked in the early 1970s and has steadily declined since then as the two major political parties polarized. (3)

Primaries and Caucuses

The second reform was to create primaries and caucuses to nominate candidates to run for office. Instead of having a few party “bigwigs” in the proverbial smoke-filled backrooms deciding which people to run for office, reformers pushed through mechanisms that allow politically active—but otherwise ordinary—people to make those decisions. A primary is an election before the general election in which people vote for one of several possible nominees. A caucus is a meeting—or a series of meetings—at which party members gather, deliberate, and choose nominees that they support and where they often choose delegates for state or national political conventions. Most states rely on primaries to nominate party candidates for each office. In a closed primary, only people who are registered with a particular party can vote in that party’s primary. In a closed primary state, only Republicans vote in the Republican primary, only Democrats in the Democratic primary, and typically those who registered as Independents or unaffiliated can vote in neither primary. In an open primary, voters can vote in the party primary of their choice, but not in both. Another version is the blanket primary, in which voters can essentially split their ticket within the Democratic and Republican primaries. You could vote in the Republican gubernatorial primary, but then vote in the Democratic primary for senator. Participation in primaries and caucuses tends to be quite low, usually less than 10 percent nationally, which is an incentive for you to get involved, as your individual vote is magnified by the low turnout.

Voter Registration

The final state-level reform that affects today’s politics is the requirement that citizens register to vote sometime prior to election-day. Registration to vote is a double-edged sword that has both laudatory and pernicious effects. Let’s talk first about the benefits of voter registration. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, American elections were often corrupted by people who voted multiple times, people who sold their votes, or by people casting votes on behalf of dead or otherwise fictitious people. According to historian Adam Smith, “The most acute periods of concern about electoral fraud have coincided either with a big influx of immigrants or with an extension of voting rights to African Americans, or both.” (4) By having people pre-register to vote, election officials can create an official list of voters and can check your name off the list once you’ve voted. Most states have a requirement that people register to vote before the election, and this has greatly cleaned up American elections. However, this does place a burden on the citizen to get themself registered before the deadline. Deadlines vary from one state to another. It also opens up opportunities for partisan state officials to purge voter registration lists of people who might disproportionately vote for their opponents. More about that in the chapter on voter suppression.

References

- Chauncey DeVega, “How Trump Will Cheat in This Election—and How Dems May Bilk Bernie,” Alternet. February 28, 2020.

- Jill Lepore, “Rock, Paper, Scissors: How We Used to Vote,” The New Yorker. October 6, 2008.

- Ronald Brownstein, “Voters Don’t Split Tickets Anymore,” The Atlantic. September 1, 2016. Geoffrey Skelley, “Split-Ticket Voting Hit a New Low in 2018 in Senate and Governor Races,” FiveThirtyEight. November 19, 2018.

- Adam Smith, “A Brief History of ‘Election Rigging’ in American History,” History Extra. November 3, 2106.

Media Attributions

- Ballot 2016 © Corey Taratuta is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license