Chapter 68: Civil Rights Case Study–Race

“We claim exactly the same rights, privileges and immunities as are enjoyed by white men—we ask nothing more, and will be content with nothing less.”

—Declaration of the Colored Mass Convention in Mobile, Alabama in April 1867 (1)

“In affirming that Black Lives Matter, we need not qualify our position. To love and desire freedom and justice for ourselves is a prerequisite for wanting the same for others.”

—Belief Statement of Black Lives Matter, retrieved in 2020. (2)

African Americans are certainly not the only group of Americans to have experienced discrimination at the hands of the government, corporations, or their neighbors. Yet it is true that they have been the victims of broader, more systemic forms of discrimination over longer periods of time than other racial or ethnic groups in the United States. Further, the legal changes that resulted largely from the Black Civil Rights Movement have revolutionized life in the United States for all people. Therefore, we will use this window into American political history to illustrate key developments in civil rights.

Race and Civil Rights Before and After the Civil War

Most Americans are not taught in school how close the country came prior to the Civil War to institutionalizing a race-based (and probably gender-based) republic that very likely would have persisted until today. In his farewell address to Congress in December, 1860, Democratic President James Buchanan proposed to amend the Constitution to allow states to affirm the right to hold slaves, allow slavery in the territories, and recognize the rights of slave owners to recover runaways wherever they fled. Congressman Thomas R. Nelson of Tennessee proposed a Constitutional amendment to forbid anyone from voting “unless he is of the Caucasian race, and of pure, unmixed blood.” Most significantly, Senator William H. Seward and Representative Thomas Corwin succeeded in getting both houses of Congress to pass by 2/3 vote an amendment—known as the Corwin Amendment—which said the following: “No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” Outgoing President Buchanan expressly supported this amendment, and incoming Republican President Abraham Lincoln had “no objection” to it. Maryland and Kentucky had already ratified the Corwin Amendment before South Carolinian militiamen fired on federal forces at Fort Sumter, beginning the Civil War. (3)

Prior to the end of the Civil War, most Blacks were slaves, and the legal position of free Blacks was tenuous. The Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) is particularly instructive in this regard. Dred Scott, a slave from Missouri, sued his owner for freedom based on the fact that his owner had taken him to Illinois, a free state, and to the Wisconsin Territory, a free territory. Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled that Scott did not have standing to sue and summed up free Blacks’ precarious position when he answered his own summation question: “Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?” The Court answered a resounding “No,” which was its way of saying that Blacks—slave or free—could not ever expect to become full and equal members of the American political community.

In 1861, eleven Southern states seceded from the Union to create a slave-owning independent republic. After a bloody Civil War in which 620,000 people were killed, the North defeated the South. In the wake of the North’s victory in the Civil War, Congress passed three amendments to the Constitution that we’ll refer to as the Civil War Amendments. Securing passage of these amendments was difficult. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, and only barely passed with the necessary two-thirds vote. The Fourteenth Amendment defined citizenship as belonging to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, but its most important component for this chapter is its civil rights clause, which mandated that all people receive the “equal protection of the laws.” The Fifteenth Amendment provided that citizens shall not be denied voting rights based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Many Democrats were apoplectic over passage of these amendments, arguing that they would lead to racial equality, social disorder, interracial marriage and even to the collapse of Western civilization. (4)

In order to give the civil rights clause practical effect, Congress passed several Civil Rights Acts during Reconstruction (1865-1877), including the Civil Rights Act of 1875. This law stipulated that people must be allowed full and equal access to public accommodations—public facilities as well as private businesses that serve the general public, like theaters, inns, restaurants, etc.—regardless of their race or color. This was the last civil rights bill to pass Congress for eighty-two years. When President Rutherford B. Hayes removed federal troops from the South in 1877, Whites moved quickly to reinstate a racial hierarchy resembling the one that had developed under slavery.

The majority of Southern Whites had no intention of allowing Blacks to vote, to be treated equally by the law, or to develop economic independence. In the years immediately after the Civil War, Southern states passed a series of laws that became known as Black Codes, which kept as many African American citizens in conditions of servitude as possible. Blacks were forbidden from self-employment, and thereby denied trades like blacksmithing, which they may have learned while they were slaves. More importantly, Black Codes required Blacks to sign “annual labor contracts with plantation, mill, or mine owners. If African Americans refused or could show no proof of gainful employment, they would be charged with vagrancy and put on the auction block, with their labor sold to the highest bidder. . . [If] they left the plantation, lumber camp, or mine, they would be jailed and auctioned off.” (5) And, of course, Whites discriminated rampantly by not allowing Blacks to access basic commercial businesses.

Many court cases resulted directly from passing the 1875 Civil Rights Act, as Blacks continued to be refused service on account of their race at inns, hotels, railroads, and theaters around the country. In Tennessee, Sallie J. Robinson purchased a ticket to ride on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad but was removed by the conductor because she was Black. In Missouri, W. H. R. Agee was denied accommodation at the Nichols House Inn because he was Black. Similarly, Bird Gee was not allowed to eat at an inn in Topeka, Kansas because he was Black. In San Francisco, George M. Tyler was not allowed to attend a production at Maguire’s Theatre because he was Black. (6) These four cases reached the Supreme Court in 1883 and were decided together as the Civil Rights Cases (1883). This was an important test of the meaning of civil rights and the Fourteenth Amendment’s mandate that no state may deny any person the equal protection of the laws. In a devastating decision for those who believed in equality, eight of the nine Supreme Court justices ruled in favor of private business owners in these cases and overturned the 1875 Civil Rights Act as unconstitutional. How could the Court rule that this Act was unconstitutional—a law designed to guarantee the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment? The Court ruled that while states must not discriminate, the owners of private businesses were free to discriminate against potential customers on the basis of race. Justice Bradley, writing for the majority, said that “Civil rights, such as are guaranteed by the Constitution against State aggression, cannot be impaired by the wrongful acts of individuals, unsupported by State authority in the shape of laws, customs, or judicial or executive proceedings.”

There was one dissenter in the Civil Rights Cases—Justice John Marshall Harlan—who argued that the states were complicit in the so-called private discrimination of businessmen. He wrote, the “keeper of an inn is in the exercise of a quasi-public employment. The law gives him special privileges and he is charged with certain duties and responsibilities to the public. The public nature of his employment forbids him from discriminating against any person asking admission as a guest on account of the race or color of that person.” Unfortunately, Harlan was alone among the justices in being many decades ahead of his time. The decision in the Civil Rights Cases sent a huge message to businessmen that the United States Constitution would not stand in the way if they wanted to refuse service to Blacks. Many did just that—and this behavior was not limited to the South, nor was it only targeted at African Americans.

The Supreme Court sent an even more disastrous signal in the case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In 1890, the Louisiana legislature passed the Separate Car Act requiring that all trains operating in the state be segregated by race and forbidding people from “going into a coach or compartment to which by race he does not belong.” Most train companies resented the costs of putting extra cars on their trains to meet the Separate Car Act requirements. Train companies and a New Orleans civil rights group known as the Committee of Citizens worked with New York lawyer Albion Tourgee to bring suit against the law. This suit was to be a test case, and the Committee needed someone to violate the law, to be punished, and have standing to sue. On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy purchased a first-class ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad’s train running from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana, and took a seat in a car reserved for Whites only. Plessy, a married shoemaker whose heritage was African and French, has been referred to as one-eighth Black. Indeed, press accounts of the time indicate that the train conductor had to ask Plessy his race before he was arrested for being in the “wrong” car. The Committee of Citizens hoped that the Supreme Court would rule in favor of Plessy, for surely this was a violation of the civil rights clause of the Fourteenth Amendment: Here is a state law that mandated segregating train passenger according to race. But the Supreme Court upheld the law as constitutional, arguing that no violation of the civil rights clause had taken place because the passengers were all treated equally, albeit in a segregated fashion. This reasoning became known as the separate but equal doctrine and was the rationale to officially sanction segregation for the next six decades. Justice Harlan was again the lone dissenter; he argued that, “In respect of civil rights, common to all citizens, the Constitution of the United States does not, I think, permit any public authority to know the race of those entitled to be protected in the enjoyment of such rights.” His argument did not carry the day and the precedent set by Plessy allowed separate but equal to characterize American life. (7)

Categories of Racial Discrimination in the Twentieth Century

Discrimination against African Americans took many forms, not all of which can be covered here. However, you should be aware of the following five categories of discrimination:

Segregated Public Accommodations—Using as precedents the Civil Rights Cases (1883) and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), states and businessmen freely segregated and excluded Blacks as well as other racial and ethnic group members. Just about any form of public accommodation you can think of was segregated somewhere at some time in the United States—and again, this practice was not restricted to the South. Public accommodations such as trains, buses, drinking fountains, hospitals, cemeteries, parks, beaches, and swimming pools were segregated. Private business owners of gas stations, hotels, inns, theaters, restaurants, lunch counters, and the like were free to refuse service to African Americans and others.

One might be tempted to think of segregated public accommodations as the least objectionable form of discrimination. After all, it does not affect one’s overt political equality the way that prohibitions against voting might. One would be wrong in such thinking. Clearly, the victims of segregated public accommodations did not feel this way, and the reasons are obvious. Segregated public accommodations placed an omnipresent badge of civic inferiority on its victims that shrank their universe of social, economic, and political possibilities. This was especially true given that segregation was backed up by actual or threatened violence. A great resource in helping us understand this perspective is Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Talk About Life in the Segregated South. In that book, Ann Pointer, a resident of Macon County, Alabama, described the impact of not having access to public transportation:

“We could not ride the buses although we were paying taxes. But we couldn’t ride those buses. Nothing rode the bus but the whites. And they would ride and throw trash, throw rocks and everything at us on the road and whoop and holler, ‘nigger, nigger, nigger,” all up and down the road. We weren’t allowed to say one word to them or throw back or nothing, because if you throw back at them you was going to jail.” (8)

Violating the rules and norms of segregated public accommodations was life-threatening for Blacks all across America, albeit with obvious regional and local differences. Traveling for business or family visits took on a very different character for African Americans, as they had to be careful about where they could safely go, where they could find a hotel or restaurant that would serve them, or where they could find a welcoming gas station. In 1937, Victor H. Green, a New York City postman, created the first Green Book, a reference guide to tell Blacks where they could safely go in the New York Metropolitan area. He updated and expanded the Green Books every year, encompassing more and more of the country. The first edition was fifteen pages long, and the final edition in 1967 was ninety-nine pages long. The book even listed private residences who would welcome Black travelers to stay in areas where there were no welcoming hotels. (9)

Segregated Housing—There have been many forms of housing discrimination in American history. You should know about three of them. Many cities used overt city ordinances that divided the town into racial zones and mandated that residential property in “White” areas be purchased by Whites, while property in “Black” areas be purchased by people of color. In a case out of Louisville, Kentucky, the Supreme Court ruled these kinds of city ordinances unconstitutional in 1917 (Buchanan v. Warley), but the practice continued for decades after that decision.

Another form of housing discrimination was racially or religiously restrictive covenants, which were agreements entered into between buyer and seller that restricted the future sale of the property to only certain kinds of people. The Court ruled against these kinds of covenants in 1948, when the Shelley family in St. Louis successfully challenged a racial covenant on their home (Shelley v. Kraemer), but it was very difficult to enforce the Court’s ruling until the Fair Housing Act passed in 1968. Even though they are no longer enforceable in real estate transactions, these kinds of covenants are still on the books across the country because it’s actually difficult for individual homeowners to get them removed. What did these covenants look like? Here are but two examples:

“…no part of said property nor any portion thereof shall be for said term of fifty years occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended thereby to restrict the use of said property for said period of time against the occupancy of owners or tenants of any portion of said property for residence or other purpose by people of the Negro or Mongolian race.” [Covenant initiated in the Greater Ville neighborhood of St. Louis, Missouri, in 1911]

“That neither said lots nor portions thereof or interest therein shall ever be leased, sold, devised, conveyed to or inherited or be otherwise acquired by or become property of any person other than of the Caucasian race.” [Covenant initiated in the El Cerrito neighborhood of San Diego, California, in 1950] (10)

The third form of housing discrimination took the form of redlining, which was a practice once encouraged by the federal Home Owner’s Loan Corporation in which minority neighborhoods were red lined, meaning that loans would be very difficult to get and/or expensive. This institutionalized discrimination in government-backed mortgages made it difficult for Black families in particular to build home equity, which is the primary way that most families build wealth. (11) These forms of housing discrimination were perpetuated by Whites who did not want to live in integrated neighborhoods and who often committed or threatened violence. The legacy of housing segregation is apparent all over the United States, and it is not an accident. As activist and author Tim Wise explains,

“The so-called ghetto was created and not accidentally. It was designed as a virtual holding pen—a concentration camp were we to insist upon honest language—within which impoverished persons of color would be contained. It was created by generations of housing discrimination, which limited where its residents could live. It was created by decade after decade of white riots against black people whenever they would move into white neighborhoods. It was created by deindustrialization and the flight of good-paying manufacturing jobs overseas.” (12)

Wise is on to something that we need to remember. The world that we see today is always a legacy of the past, and often that past includes intentional decisions to construct the future that we occupy. In other words, the unequal and somewhat segregated living arrangements that we see today were in large part the result of conscious government policies and decisions that happened before we were born. Richard Rothstein, a Distinguished Fellow of the Economic Policy Institute, outlined this well in his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. “Racial segregation in housing,” Rothstein wrote, “was not merely a project of southerners in the former slaveholding Confederacy. It was a nation-wide project of the federal government in the twentieth century, designed and implemented by its most liberal leaders.” (13) Rothstein documents in great detail the government policies designed to segregate America: The Federal Housing Administration’s bankrolling of segregated housing developments and evading the Supreme Court’s ruling striking down racially restrictive covenants; the use of government housing projects to concentrate Black residents while promoting single-family home ownership to Whites; the suppression of Black wages through the lack of federal action until the mid-1960s to enforce anti-discrimination in the workplace; the tacit support of federal agencies for redlining by banks. And, lest we forget, the profession of realtors went to considerable lengths to maintain the right of property owners to discriminate with respect to whom they would sell or rent housing. Famously, Ronald Reagan made the following statement in 1966 in defense of just this kind of discrimination: “If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house, he has a right to do so.” For much of the 20th Century, the real estate industry actively worked against free market principles in the American housing market and in so doing, “dramatically reshaped the country for all Americans” by constructing segregated neighborhoods north and south, east and west. (14)

Segregated Education—The separate but equal doctrine was applied to education with a vengeance and without any pretense of equality between Black schools and White schools. Almost all school districts in the South were segregated from the late nineteenth century into the 1960s. Some school districts outside of the South were segregated as well, including the schools in the nation’s capital. The first legal crack in segregated schools came from California and dealt with Latinx students. In 1946 the 9th Federal Circuit Court struck down separate “Mexican schools” in Orange County, with the Court saying that “A paramount requisite in the American system of public education is social equality. It must be open to all children by unified school association regardless of lineage.” (15) The NAACP Legal Defense Fund took up a number of school segregation cases in the 1950s, one of which was that of Linda Brown, who was denied admittance to her neighborhood school and instead had to take a bus to a segregated school. In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), the Supreme Court ruled 9-0 that segregated schools were inherently unequal, reversing the Plessy doctrine as it applied to education. Thus, de jure, by law, segregation is unconstitutional, but de facto, in fact, segregation is alive and well in America’s schools. (16)

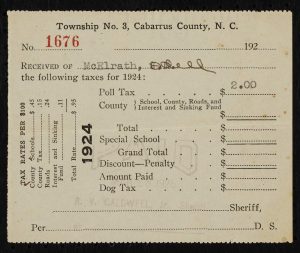

Voter Discrimination—The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed the right to vote regardless of race, but Southern white elites did not want African Americans to vote. Beginning after Reconstruction ended in 1877, southern Democrats regained control over state legislatures and undertook several measures to keep blacks from voting. One measure was extralegal and consisted of outright intimidation. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan lynched Blacks, shot those who were politically active, bombed their houses, got them fired from their jobs, burned crosses to frighten communities, and spied on civil rights organizations. In many southern states, literacy tests were used to keep African Americans from registering to vote. Potential voters were required to take an often-subjective “test” of their literacy, their knowledge of the federal or state constitution, or their knowledge of completely arcane bits of information. Literacy tests were combined in some cases with good character clauses, in which people needed to be certified as being of good character in order to register. Grandfather clauses automatically registered anyone–Whites–whose male ancestors were eligible to vote at some date before the Fifteenth Amendment passed. Southern states instituted white primaries, in which people of color were barred from voting. This was important because the South was solidly Democratic at the time, meaning that the primary race was often of greater significance than the general election in November. Poll taxes were also used to discourage Blacks from voting. Finally, Southern Whites used racial gerrymandering to design election districts that bisected African Americans populations, thereby diluting their numbers should they actually register to vote.

Affirmative Action for Whites—Most White Americans don’t realize the extent to which they have benefited first from slavery and second from government policies that privileged Whites. It almost goes without saying that many Whites and White-owned companies benefited directly from the 300 years of labor theft that was slavery—although there is an argument to be made that many poor Southern Whites saw their wages artificially suppressed by slavery’s existence. Ira Katznelson, Columbia University political science and history professor, has documented how twentieth-century government policies designed to help all Americans ended up being tailored in ways that disproportionately helped White Americans. This was accomplished primarily due to the powerful Southern Democratic voting bloc that resulted from the Solid South phenomenon. Southern Democrats dominated congressional committees and insisted on certain racist concessions when it came to policy making.

How did this work? Many of the New Deal programs were specifically designed to disadvantage most African Americans. For example, most Southern Blacks at the time were working as domestic maids or farm laborers. Southern politicians insisted that New Deal legislation that promoted labor unions, set minimum wages, set maximum hours, and established Social Security explicitly exclude maids and farm workers. As Florida Representative James Mark Wilcox put it, “You cannot put the Negro and the White man on the same basis and get away with it.” (17) Social Security is a classic example: according to Katznelson, fully 65 percent of Blacks were initially excluded from the program because of concessions to Southern politicians. The same was true of the National Recovery Administration, the National Labor Relations Board, and the Fair Labor Standards Act. Even the GI Bill suffered from Southern meddling. Largely crafted by Representative John Rankin of Mississippi—an avowed racist—the law was written in a way that did not disturb segregation in the South. The GI Bill offered veterans educational grants, subsidized home mortgages and business loans, assistance finding a job, and job training—but all of this was administered at the local rather than federal level. Banks could still red-line Blacks’ mortgage applications, colleges could still deny Blacks entrance, and local jobs programs could still discriminate. Thus, the GI Bill was an undoubted boon to White veterans, but often an unfulfilled promise to Black veterans.

Has affirmative action for Whites ended? Mostly, although higher education is a sector that still practices a sneaky form of it. While the Supreme Court struck down the ability of colleges and universities to use race as one of many factors in making admissions decisions, legacy admissions and admissions for the children of donors and faculty at elite public and private schools still skews in favor of Whites. At Harvard, for example, fully 43 percent of White students were admitted using these kinds of preferences–and three-quarters of them would have been rejected had they not been the children of alumni, donors, or faculty, or had they not played particular sports like lacrosse or sailing. (18) Elite public universities also skew disproportionately White by recruiting the children of wealthy people who reside out of state. For example, “places like the University of Alabama give an effective 45 percent bump to the children of the top 1 percent,” which happen to be predominantly White. (19)

Important Civil Rights Legislation

Beginning in 1957, the federal government passed several civil rights laws, three of which you need to know in any U.S. Government course. They are the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Civil Rights Act of 1964—Demanded by civil rights leaders for decades, proposed by President John F. Kennedy, and pushed through by President Lyndon Johnson after Kennedy’s assassination, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a monumental political achievement. It was truly bi-partisan legislation, with a majority of congressional Republicans and Democrats supporting it. However, Southern Democrats and a few Republicans almost unanimously opposed it. Notably, Republican Senator Barry Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act. Because Goldwater was the Republican Party’s nominee for president that year, it was an indication of the Republican turn against civil rights for decades to come. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 did the following:

- Outlawed discrimination in voter registration, but this section had poor enforcement language.

- Established that “All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, and privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any place of public accommodation, as defined in this section, without discrimination or segregation on the ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.”

- Authorized the U.S. Attorney General to sue in cases where people were denied the equal protection of the laws, unequal access to public accommodations, or equal access to public schools and colleges.

- Banned discrimination in programs that receive federal assistance.

- Banned employment discrimination directed at “any individual because of his race, color, religion, sex or national origin.” This includes hiring, firing, conditions of employment, and compensation.

- Created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which is empowered to make prosecution recommendations to the U. S. Attorney General regarding employment discrimination. (20)

Voting Rights Act of 1965—After the Civil Rights Act passed and after President Lyndon Johnson trounced Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election, Johnson vowed during his 1965 State of the Union address to “eliminate every remaining obstacle to the right and the opportunity to vote.” The Voting Rights Act was designed to shore up a weakness of the Civil Rights Act—namely, that it was insufficiently aggressive in defending the right of all people to vote regardless of race. Passed later in 1965—again, over Southern opposition—the Voting Rights Act did the following:

- Established that “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

- Established that whenever the U. S. Attorney General was engaged in a proceeding against a state or district that was violating the right to vote, federal authorities were empowered to come in and take over the voting registration and election management from local authorities until the problems were rectified.

- Established that “no citizen shall be denied the right to vote in any Federal, State, or local election because of his failure to comply with any test or device in any State” that has used such tests or devices to disenfranchise people on the basis of race or color.

- Established a pre-clearance provision whereby states or political subdivisions of states who have engaged in racially motivated voter discrimination need to submit “any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting different from that in force or effect on November 1, 1964” to the Justice Department for approval.

Note that in Shelby County v. Holder (2012), the Supreme Court struck down the Voting Rights Act’s important “pre-clearance” provision, allowing primarily Southern states to change their voting laws without having them approved ahead of time by the Justice Department. This opened the gates for many Republican-led state legislatures to pass without Justice Department review onerous voter I.D. laws that fell heaviest on the poor, the elderly, and people of color. Writing in dissent, Justice Ginsberg argued that “Throwing out preclearance because it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” (21)

Civil Rights Act of 1968—The Civil Rights Act of 1968 was primarily designed to address two issues that previous legislation had not—namely, applying the Bill of Rights protections on Native American reservations and equal access to housing. Thus, in popular parlance, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 encompasses the following two main pieces:

- Indian Civil Rights Act—This part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 applied most of the Bill of Rights and Constitutional protections to Native Americans living under the various tribes’ jurisdiction. It stipulated that no Indian tribe shall prohibit free exercise of religion, free speech, free press, or the right of people to assemble peaceably and petition for redress of grievances. Further, no Indian tribe can violate the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable and warrantless searches and seizures. Indian tribes were forbidden from conducting unreasonable and warrantless searches and seizures, taking of private property without just compensation, violating fair trial procedures, and inflicting cruel and unusual punishments.

- Fair Housing Act—This part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 outlawed housing discrimination. The Act made it unlawful to “refuse to sell or rent after the making of a bona fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for the sale or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a dwelling to any person because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status, or national origin.” Further, it made it unlawful to “discriminate against any person in the terms, conditions, or privileges of sale or rental of a dwelling, or in the provision of services or facilities in connection therewith, because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status, or national origin.” Another interesting part of the law is that it made it unlawful “to represent to any person because of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, or national origin that any dwelling is not available for inspection, sale, or rental when such dwelling is in fact so available.”

These three laws set the framework for breaking down de jure discrimination—that is, discrimination written into laws and official policies at the federal, state, local, and company levels. What they did not do was eliminate de facto discrimination, which is discrimination in everyday life that is unsupported by law or policy. The issues that remain, according to civil rights leaders, are no less significant: dealing with the lasting impact of past de jure discrimination, discriminatory policing, social prejudice affecting how people interact in all sorts of settings, and unequal access to economic and educational opportunities. Some of these challenges can be addressed by public policy, while others are difficult to address via government action. For example, Gene Slater, an expert on housing discrimination, writes that “To this day, an estimated four million housing discrimination complaints each year go uninvestigated, and fair housing remains largely unenforced.” (22)

References

1. Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019. Page 94.

2. No author, “What We Believe,” Black Lives Matter. No date.

3. The text of the Corwin Amendment retrieved from the University Maryland. See also Michael A. Bellesiles, Inventing Equality: Reconstructing the Constitution in the Aftermath of the Civil War. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020. Pages 68-70.

4. Michael A. Bellesiles, Inventing Equality: Reconstructing the Constitution in the Aftermath of the Civil War. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020. Pages 111-198.

5. Carol Anderson, White Rage. The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide. New York: Bloomsbury. 2017. Page 19.

6. Peter Irons, A People’s History of the Supreme Court. New York: Penguin Books. 1999. Page 212.

7. This account is drawn from Steve Luxenberg, Separate. The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America’s Journey from Slavery to Segregation. New York: W. W. Norton. 2019.

8. William H. Chafe, Raymond Gavins, and Robert Korstad, editors, Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Talk About Life in the Segregated South. New York: The New Press, 2001. Pages 173-74.

9. Jacinda Townsend, “How the Green Book Helped African American Tourists Navigate a Segregated Nation,” The Smithsonian Magazine. April, 2016. Available here.

10. Cheryl W. Thompson, et al., “Racial Covenants, a Relic of the Past, are Still on the Books Across the Country,” National Public Radio Morning Edition. November 17, 2021.

11. Tracy Jan, “Redlining Was Banned 50 Years Ago. It’s Still Hurting Minorities Today,” The Washington Post. March 28, 2018.

12. Tim Wise, “White America’s Greatest Delusion: ‘They Do Not Know It and They Do Not Want to Know It.'” Alternet. May 6, 2015.

13. Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1917. Quote is from page xii.

14. Gene Slater, Freedom to Discriminate: How Realtors Conspired to Segregate Housing and Divide America. Berkley, California: Heyday, 2021. Reagan quote is on the front piece and the other quote is from page 8.

15. Mendez v. Westminster (1947).

16. Emily Richmond, “Schools Are More Segregated Today Than During the Late 1960s,” The Atlantic. June 11, 2012.

17. Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action was White. New York: W. W. Norton. 2015. Page 60. This whole section draws from this source.

18. Fabiola Cineas, “Affirmative Action for White College Applicants is Still Here,” Vox. July 6, 2023.

19. Kevin Carey, “These Schools Also Favor the One Percent,” The Atlantic. August 15, 2023.

20. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 at Our Documents.

21. Michael Waldman, The Fight to Vote. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016. Page 233.

22. Gene Slater, Freedom to Discriminate: How Realtors Conspired to Segregate Housing and Divide America. Berkley, California: Heyday, 2021. Page 7.

Media Attributions

- Whites Only Housing © Arthur S. Siegel is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Poll Tax Receipt © Levine Museum of the New South is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Civil Rights Act 1964 © Cecil Stoughton, White House Press Office is licensed under a Public Domain license