Chapter 60: Political Violence

“Black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police over the life course than are white men . . . American Indian men are between 1.2 and 1.7 times more likely to be killed by police than are white men . . . Latino men are between 1.3 and 1.4 times more likely to be killed by police than are white men . . .”

—Frank Edwards, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito (1)

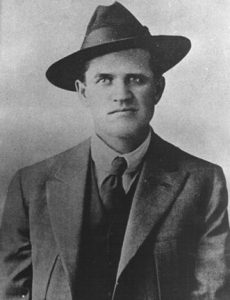

“Others Take Notice! First and Last Warning!”

—Note pinned to the body of union organizer Frank Little, who was found in 1917 hanging from a railroad trestle in Butte, Montana (2)

Three Forms of Political Violence

A Swedish sociologist named Johan Galtung made important contributions to our understanding of political violence. You should be familiar with Galtung’s three forms of violence that can characterize any political system.

Direct violence is fairly self-explanatory. It refers to a specific destructive act by a definable actor that limits the bodily or mental potential of the persons who are the object of the act. Murder, rape, assault and the like are examples of direct personal violence, as are forms of torture and verbal abuse that have physical as well as mental effects. American history has been rife with direct violence: assassinations, bombings, lynching, riots, military campaigns, and the like. Police violence is direct violence.

Structural violence refers to the same limitations of bodily or mental potential, but that result from the way political, social, or economic systems are organized, instead of via direct action by a specific individual or group. Often, there is no readily definable actor in structural violence, but people are nevertheless being hurt, killed, or mentally anguished. It’s called structural violence because violent outcomes appear to be built into the structure of the system; people are hurt because the system operates the way it does. Galtung provided some examples of structural violence: “Thus, when one husband beats his wife there is a clear case of personal [direct] violence, but when one million husbands keep one million wives in ignorance, there is structural violence. Correspondingly, in a society where life expectancy is twice as high in the upper class as in the lower classes, violence is exercised even if there are no concrete actors one can point to directly attacking others, as when one person kills another.” (3)

Cultural violence refers to “those aspects of culture, the symbolic sphere of our existence,” religion, ideology, language, art, and science, “that can be used to justify or legitimize direct or structural violence.” (4) The range of possibilities here is very wide, but you might recognize the following examples:

- Media censorship or self-censorship that minimizes the brutality of war by refusing to show certain images or describe certain events. The same can be said of media coverage of mass shootings, with the media always stopping short of showing bodies riddled with gaping bullet holes.

- The constant association of the words “patriot” and “hero” with military figures, while those terms are almost never associated with anti-war demonstrators, children striking for environmental awareness, or teachers.

- Ideological assertions that poverty and significant inequality are natural.

- Religious exhortations to kill or shun the enemies of God.

- Educational institutions that go out of their way to avoid having students grapple with issues such as capitalism as practiced in the United States, religion, sexual orientation, environmentalism, race, class or gender, thereby blinding students to the realities of direct and structural violence associated with these dimensions of human existence.

- Constantly suppressing alternatives to economic or political realities. Media drumbeat that the status quois really the only way to arrange our businesses, our politics, and our society.

- Media glorification of “tough cops” who use violence.

Galtung referred to direct violence as a discrete event, structural violence as a process, and cultural violence as a permanence that legitimized and rendered acceptable the other two.

The Overall Pattern of Political Violence in American History

The difficulty in understanding political violence in America’s past and present is that it seems like random noise. It is not. When we focus our attention on the three forms of violence in American political history, a fairly clear ideological pattern emerges. Remember that in the chapter about the Supreme Court as an ideological actor, we talked about conservatism and progressivism. Conservatism is an ideology that defends existing privilege and power. It’s worth repeating political scientist Corey Robin’s summation: “Conservatism is the theoretical voice of . . . animus against the agency of the subordinate classes. It provides the most consistent and profound argument as to why the lower orders should not be allowed to exercise their independent will, why they should not be allowed to govern themselves or the polity. Submission is their first duty, and agency the prerogative of the elite.” (5) Progressivism, on the other hand, is an ideology that believes in using the power of government to help all people live full lives, solve social problems, and counter the power of business interests. It is an emancipatory ideology in that it hopes to disrupt established hierarchies, promote equal rights and opportunity, and create a society that is less economically and politically unequal. Conservatives and progressives oppose each other because the progressive project is directly opposed to the conservative project.

It’s plain from examining America’s past and present that political violence is much more frequently used to further conservative aims than progressive ones. Time and time again, those with power who feel their privileges are threatened have gone to drastic lengths to aggressively defend their position. They have repeatedly engaged in direct violence and benefited from structural violence that keeps subordinated people in their place. They have relied on assassination, bombing, lynching, rioting, military or police assault, purging people from their jobs, violence-first policing techniques, and mass incarceration. Progressive groups, on the other hand, are far more likely to march in the streets for civil rights, hold anti-war demonstrations in front of public buildings, tie themselves to the White House gates to protest the lack of women’s suffrage, try to peacefully block construction of nuclear power plants, and other similar actions.

To be sure, progressives have sometimes employed violence to further their goals. Consider that some leftist groups like the Weather Underground or the Black Liberation Army bombed ROTC buildings on colleges campuses as well as other buildings they associated with American imperialism and racism. Usually, these groups took pains to detonate their bombs when they thought the buildings were empty, so relatively few people were killed by the thousands of bombings that took place over several decades. (6) Altogether, this left-wing bombing campaign killed far fewer people than did Timothy McVeigh’s one bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City—an act that was specifically intended to kill many people and start an uprising. It is also true that some environmentalist and animal rights groups have destroyed property to further their causes. David Helvarg argues that such violence has more than been matched by violence directed at environmentalists. (7)

Examples of Direct, Structural and Cultural Violence

Let’s review several prominent examples of how direct, structural, and cultural violence interact to maintain privilege and sustain existing power hierarchies. Keep in mind that what follows is necessarily superficial because this is a survey text of American politics that has to cover many topics. These are just a few examples among many we could have explored. Imagine the direct, structural, and cultural violence that for years kept women in subordinate positions to men, and still does, despite centuries of legal, social, and cultural progress. Consider the direct violence inflicted upon children separated from their undocumented parents and put in holding cells, and the structural violence of an economic system that allows agribusinesses to pull low skilled workers into the country in the first place, only to terrorize them with harassment, precarious employment, exposure to toxic chemicals, and the ever-present threat of deportation. (8) Reluctantly setting aside those and many other cases, let’s look at three main examples.

White Nationalism

If one were to take a cynical view of American political history, it would be tempting to sum it up as follows: A group of White merchants and plantation owners got together to establish that all men are created equal, and then spent the ensuing centuries proving to people of color that they didn’t really mean to include them in their understanding of universal equality. In fact, whenever people of color demanded that we actually live up to our founding principles, Whites in positions of economic and political power acted to violently suppress those demands.

Often, maintaining White power and privilege took the form of direct violence. America’s history of lynching is a good example. Lynching refers to the extra judicial killing by persons or a mob that is incited to take the law into its own hands. From 1882 to 1968, there were 4,743 documented lynchings in the United States, and nearly 73 percent of them were of Black people. (9) Surely, many more people were lynched in the period from the end of the Civil War to 1882, and there are probably some lynchings in the later period that did not get recorded. Or consider the targeted assassinations and bombings that were directed at civil rights leaders. In 1963, a White supremacist Klansman assassinated Medgar Evers, the Mississippi Field Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Evers was ambushed and shot in the back as he walked from his car to his house. He died in front of his two small children. The assassin, Byron De la Beckwith, was twice acquitted by all White juries—the fact that African Americans were routinely excluded from juries is a great example of structural violence—and congratulated by the state governor. The case was finally reopened 30 years later, and De la Beckwith was convicted of murder in 1994. (10) Let’s stay in Mississippi and remember the 1964 killings of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner, three young men who were working on voter registration, education, and civil rights when they were stopped for speeding and taken to the Neshoba County sheriff’s office. They disappeared after that. After six weeks of searching—during which the bodies of nine (!) Black men were found in the nearby woods and swamps—the bodies of Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner were found buried in an earthen dam. Eighteen White men were indicted, and eventually seven were convicted and served time. (11)

These examples of White supremacist violence are but a small sampling of the broader universe of such actions that range from colonial times to the present. Consider the tragic example of the White coup in Wilmington, North Carolina. White supremacists, fed up that Wilmington had developed into a prominent example of a successful mixed-race community, stormed through the town on November 10, 1898, murdering and beating people, destroying property, and forcing progressive people to flee. All together, the mob of Whites killed at least 60 Black men. (12) And we should not forget that the threat of violence can be just as effective. Hateful graffiti; nooses put near houses, dorm rooms, or school lockers; and racist chants by large groups serve to put people of color on notice that they should not venture into spaces and roles that “belong” to Whites.

The effects of direct violence and threats are reinforced through structural violence. The school to prison pipeline, for example, affects young people of color more than it does Whites. This pipeline refers to the way in which students are identified as struggling or disruptive in school and funneled out of schools to juvenile detention and criminal justice systems. Facing disproportionately more suspensions, expulsions, and arrests in schools, and often excluded from honors or college-track courses, students of color are more likely to enter juvenile justice systems, which further limits their opportunities, often resulting in their incarceration as adults. (13)

Or consider another example. The United States has a problem with its militarized approach to policing, which seems to be a function of three things. America is a heavily armed society, with more personal firearms than there are people to carry them. This means that police have to go into every domestic violence situation, every robbery at a convenience store, and every traffic stop with the knowledge that the person they encounter could very well be armed. The second factor is that war metaphors have taken over our cultural understanding of the relationship between the police and society. Since the late 1960s, our politicians have led us into waging twin wars on crime and drugs, and our movies are rife with scenes of uncivilized criminals kept at bay only through the armed response of police. Finally, America’s imperialist and warlike approach to global relations has ensured a steady stream of military equipment and tactics that are made available to police forces around the country. The militarized approach to American policing is a plague that falls on all of us, but disproportionately on people of color. As the writer Mychal Denzel Smith argued in his analysis of a midnight SWAT raid in Detroit in which a seven-year-old girl named Aiyana Stanley-Jones was shot while she slept, “Part of what it means to be Black in America now is watching your neighborhood become the training ground for our increasingly militarized police units.” (14) In an interesting study in the Journal of the National Medical Association, researchers found that state-level structural racism—as reflected in residential segregation and disparities in incarceration rates, educational attainment, employment, and economic indicators—is directly related to the prevalence of police shootings of unarmed Black suspects. The authors concluded that “For every ten-point increase in the state racism index, the Black-White disparity ratio of police shooting rates of people not known to be armed increased by 24%.” (15)

Colonists Over Indigenous Peoples

As noted toward the beginning of this text, America was founded by European colonists who continued the colonial expansion until it consumed the continent. No one knows for sure how many native people inhabited the Americas before the Europeans came. Estimates range from a low of 1.8 million people to a high of more than 100 million people. Prior to 1492, the Americas possessed sophisticated cities, many agricultural settlements, and uncounted nomadic groupings. In a historical blink of an eye, those civilizations and populations were decimated. By 1900, the population of Native Americans had dropped to around half a million. This disaster destroyed more than people. As Charles Mann has written, “Languages, prayers, hopes, habits, and dreams—entire ways of life hissed away like steam.” (16)

The majority of this assault came in the form of pandemic disease: Native American populations had scant defenses against smallpox, typhoid, bubonic plague, influenza, mumps, measles, whooping cough, cholera, malaria, and scarlet fever. The remaining assault took the form of direct and structural violence, justified then and now by cultural violence.

As with our discussion of direct violence against civil rights leaders, we can only touch on a couple of illustrative examples here. Regardless of whether you look at New England, the South, the Ohio Valley and the Great Plains, or the West, the time period from the early 1600s to the official closing of the American frontier in 1900 was marked by assaults and treachery on the part of colonial invaders and counter attacks and strategic retreats on the part of indigenous people. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 must surely go down as one of the most aggressively imperialistic laws in American history. The Act euphemistically sought to “provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi.” (17) Many tribes were peacefully removed from their lands within existing states and pushed west, only to face pressures again when the frontier expanded westward. The experience of nations like the Cherokee, the Seminole, and other tribes who opted not to trade their land indicated that the polite language of the Removal Act was a front for naked aggression. According to President Andrew Jackson, the Removal Act promised what Adolph Hitler would later refer to in the context of Nazi Germany as lebensraum: Indian removal, he said, “will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters.” Cherokee leaders addressed the United States and said in no uncertain terms that “We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and original right to remain without interruption or molestation.” In what became known as the Trail of Tears, up to 100,000 indigenous people—men, women, and children—were removed from their lands in Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama and force marched during the winter of 1838-39 to new lands west of the Mississippi River. About half of the Cherokee, Muskogee, and Seminole perished along the way, and about 15 percent of the Chickasaws and Choctaws also died during the march. (18)

The progression of colonial settlement across the continent was marked by a series of massacres and battles. Starting in 1539 with a massacre in what was to become Florida to the Wounded Knee massacre in 1890, European-Americans perpetrated hundreds of attacks on unarmed indigenous people who, in turn, committed atrocities of their own as their territory and way of life disappeared under the colonial onslaught. (19) Consider just two of these events. In November 1864, a group of Arapahoe and Cheyenne camped along Sand Creek in eastern Colorado, thinking they were under the protection of soldiers at Fort Lyon. Instead, Major Scott Anthony and Colonel John Chivington planned an attack on the peaceful encampment. When they learned of the plans, some soldiers such as Captain Silas Soule, Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, and Lieutenant James Connor protested, saying that “It would be murder in every sense of the word” and a violation of pledges of safety that had been given to the tribes. The Sand Creek Massacre was a war crime, pure and simple. The encampment set no watch and was attacked by 700 soldiers at first light while its occupants slept. The cavalry, led by Chivington, killed 133 people, 80 percent of whom were women and children. Many were scalped or otherwise brutalized. (20)

Nearly two years before, the largest massacre of indigenous people occurred in what would later be southern Idaho. The Bear River Massacre in January of 1863 had a familiar story. After thousands of predominantly Mormon pioneers entered the area, the prospects of the local Shoshone people looked increasing desperate. Unable to feed themselves, the Shoshone ended up dependent on food donations from Mormon settlers. After a Native American attack on some miners, Colonel Patrick Connor led a group of volunteers from Fort Douglas to an encampment of Shoshone along the Bear River. Colonel Connor appeared to have made his decision to attack the Shoshone absent any definitive proof of their involvement in the attacks and with the full intention of not taking prisoners. The Shoshone had taken some defensive measures, but their weaponry was clearly inferior, and they were desperately short of ammunition. The troops surrounded the encampment and attacked at dawn on January 29. After a four-hour battle, the infantry and cavalry almost completely annihilated the Indian encampment. Connor, who was promoted to General after the battle, estimated that his men had killed between 250 and 300 men, women, and children—the deadliest massacre of Native Americans in U.S. history—and one observer claimed that as many as 265 women and children were among the dead. Visiting the site five years after the massacre, a Deseret News reporter wrote that “The bleached skeletons of scores of noble red men still ornament the grounds.” (21)

In addition to direct violence, the structural and cultural violence against indigenous Americans has been impressive in its impact. Even without the massacres and battles, it appears that the very machinery of colonization would have doomed them anyway. The colonial mechanism worked like this: Backed by military forces, settlers increasingly pushed into lands claimed and not claimed by the United States. Disputes between settlers and indigenous people inevitably arose and served as evidence that the Native Americans were savages. Sayings such as General Philip Sheridan’s “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead” typified the culture of the colonists. Pushed to ever marginal lands and reservations, the way of life of one tribe after another changed forever. As the invaders took the lands of Native Americans by theft, deception, and treaty, they also took steps to establish property rights and the rule of law—for themselves and their descendants—in the Wild West. (22) Native children were shipped off to American Indian boarding schools, the goal of which was to destroy indigenous language and culture, as kids were taken from their parents and assimilated into Anglo culture. Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, director for 25 years of one of these schools, famously said that his goal was to “Kill the Indian, save the man.” According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, “By 1926, nearly 83 percent of Indian school-age children were attending boarding schools.” (23) Meanwhile, communities of indigenous people were starved of capital and broad economic development by the logic of capitalism, condemning many of them to cycles of poverty, crime, ill health, and social dysfunction. Only the courageous and dedicated indigenous people who know this history have saved the remains of their cultural heritage.

Suppression of Working People

Considerable violence has been and continues to be directed at workers who refuse to take on the roles elites want them to play in America’s brand of capitalism—which is to say that violence is targeted at workers who want to organize together, demand better pay and working conditions, and who want a greater voice in the economy.

The unremitting direct violence against working men and women in American history is not something typically taught in high school. Indeed, I was not taught much about the nature of the relationship between workers and capital. I was not taught, for example, that a president as revered as Abraham Lincoln warned against giving capitalists too much power. In his 1861 State of the Union letter to Congress, Lincoln took time away from addressing the outbreak of the Civil War (!) to make publicly known his fear that capital was threatening to usurp labor as the primary consideration of government. He said “Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.” He then issued a warning to working men that they should not surrender “a political power which they already possess, and which if surrendered will surely be used to close the door of advancement against such as they and to fix new disabilities and burdens upon them till all of liberty shall be lost.” (24) Sociologist James Loewen confirmed in his study of school textbooks that despite the fact that “social class is probably the single most important variable in society,” American history textbook “treatments of events in labor history are never anchored in any analysis of social class.” (25)

The United States had a de facto civil war that lasted 100 years between the capitalist class and workers who tried to organize to better defend their interests. Let’s look at a couple of examples of direct violence to maintain the interests of elites versus workers. The first is the company tactic of strike busting when workers resorted to strikes because corporate owners would not negotiate or would not make concessions on wages or working conditions. In the nineteenth century and early part of the twentieth century, companies often used their own guards or hired outsiders to beat and harass strikers. They hired what striking workers called scabs to break strikes. A scab is a worker—often one who was unemployed or who had no prior connection to the company—who is willing to cross a picket line and work. Sometimes strike busting got way out of hand. Consider the Ludlow Massacre. In 1913 thousands of Colorado miners went on strike for better wages and working conditions as well as in protest of the feudal conditions they suffered in company-owned towns. When labor organizer Mother Jones came to Colorado to support the miners, she was arrested and deported from the state. Evicted from their shacks by the mining companies, thousands of miners and their families set up shanty towns in the Colorado hills. The largest of these tent settlements was at a place called Ludlow. On the morning of April 20, 1914, the National Guard—called in by Colorado’s governor at the behest of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Corporation, which was owned by the Rockefeller family—opened up on the camp with machine guns and then set fire to the tents. Twenty-six people were killed, including eleven children and two women. More violence followed. In total, sixty-six people were killed. No one was ever even indicted for the crime. (26)

You should be aware of two times the federal government stepped in to further the interests of the elites versus the ideological left wing. Elites were terrified at the prospect of a successful social and political revolution in the United States. To thwart this possibility, the government engaged in two Red Scares—one after each world war. We can define a Red Scare as a hyped fear of socialists and communists that is used to silence their voices as well as any progressives or leftists. In the three years following the 1917 Russian Revolution, government leaders created a Red Scare and went after socialists of all stripes. Aided by passage of the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1918, “Hundreds of Socialist leaders and other radicals were convicted of sedition and antiwar activities, and party newspapers across the country were suppressed and barred from the mails.” (27) Attorney General Alexander Palmer, fearing insurrection from leftist radicals, directed a series of raids—called Palmer Raids—that rounded up around 10,000 Communists, Socialists, and Anarchists. Over 500 of them were deported. Another Red Scare took place from 1947 to 1957 and is most closely associated with Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy from Wisconsin. Earlier, in 1940, Congress had passed the Smith Act, which made it a crime to “knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association.” Then, in 1947, Democratic President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9835, which established loyalty oaths for government employees. The House Un-American Activities Committee issued subpoenas and hauled people in to testify about their political affiliations or to rat out their co-workers and colleagues. Thousands of people—from blue-collar union workers to Hollywood stars and writers—lost their jobs. McCarthyism had a chilling effect on people advocating leftist ideas such as universal healthcare.

The civil war between capital and labor quieted somewhat after passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, which allows workers to organize and prevents unfair practices by corporations against union activity. After World War II ended, corporations lobbied for limitations on union practices, and Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which requires unions to honor existing contracts without striking, forbids unions from secondary strikes, general strikes, and wildcat strikes, and places other restrictions on unions. These two pieces of legislation, more than anything, reduced the temperature of the civil war between corporate owners and workers. Nevertheless, this struggle still bubbles below the surface of media attention. Workers are fired when they try to organize—although the company invariably cites a different reason for terminating the employee—and companies threaten to move production elsewhere unless they get concessions from workers. (28) And then there’s wage theft, or when “a worker doesn’t get fully paid for the work they’ve done. Often employers pull this off by paying for less than the number of hours worked, not paying for legally required overtime, or stealing tips.” Company wage theft against hourly workers happens regularly and amounts to nearly the value of all other property theft combined each year. (29)

Occasionally, the media accidentally lets the cat out of the bag and acknowledges that the interests of the elites who own the economy are at odds with the workers who produce the value that gets skimmed off by elites in the form of profits and dividends. One of these accidental revelations occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the April 9, 2020 edition of a CNBC show about the economy, the network accidentally juxtaposed the exuberant title of the segment “The Dow’s Best Week Since 1938” with a crawling newsfeed at the bottom of the screen about the news of the day, which said “More than 16 million Americans have lost jobs in 3 weeks.” (30) Wall Street was confident that recent stimulus packages heavily tilted to big business and financial institutions, quantitative easing, and low oil prices meant that they would weather the storm nicely. The high-flying investors had already priced the suffering of millions of low paid workers into their investment strategies.

Cultural violence continually justifies our rigged economic system and serves to deflect attention away from its inequities. Have you heard this joke? A wealthy capitalist, a worker, and an immigrant are sitting around a table. The capitalist has a plate in front of them with nine cookies on it. The worker has a plate in front of them with one cookie on it. The immigrant’s plate is empty. The capitalist says to the worker, “Be careful, the immigrant is going to try to steal your cookie.” Some version of this scenario plays out in America’s news media all the time. If workers are poor, the cause must be immigrants, foreigners, technological forces, poor education, people of a different race, or their own character flaws. It couldn’t possibly be the result of the particular way that we’ve set up our version of a market economy that gives ninety percent of the benefits to the top ten percent of families. Because if it were, we could change those rules—and it’s important to elites that ordinary Americans think that the way things are currently done is the only way they could possibly be done. To cite an example of what they do not want you to consider, we couldn’t possibly establish incorporation and tax rules that favored worker-owned cooperatives. But, of course we could, and many of us might be better off if we did just that. (31)

Final Thoughts

Political violence is a component of corporate and elite power, but we should recognize that violence has also been used by ordinary Americans who fight for change or who are so frustrated that they lash out. Think about the Donald Trump supporter who was arrested for sending explosive devices to prominent Democrats, or the Bernie Sanders supporter who opened fire on Republican congressmen who were practicing for a baseball game. (32) These are certainly disturbing events, and violence should be condemned whenever it happens regardless of target. The point of this chapter, however, is that the whole toolbox of political violence as described by Galtung is really only available to elites who have the means, motive, and opportunity to employ direct, structural, and cultural violence to achieve political ends. Their particular style of violence has the effect of nullifying direct threats to their rule, fragmenting class consciousness, deflecting attention toward red herrings, extracting income and wealth from ordinary people, and preventing full realization of how rigged the economic system has become.

References

- Frank Edwards, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito, “Risk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in the United States, By Age, Race-Ethnicity, and Sex,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. August 20, 2019.

- Rory Carroll, “The Mysterious Lynching of Frank Little: Activist Who Fought Inequality and Lost,” The Guardian. September 21, 2016.

- Johan Galtung, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research. 6(3): 1969. Page 171.

- Johan Galtung, “Cultural Violence,” Journal of Peace Research. 27(3): August, 1990. Page 291.

- Corey Robin, The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump. 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Pages 7-8.

- Bryan Burrough, Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence. New York: Penguin Books, 2016.

- David Helvarg, The War Against the Greens. New York: Random House, 1994.

- Ariel Ramchandani, “There’s a Sexual-Harassment Epidemic on America’s Farms,” The Atlantic. January 29, 2018.

- No author, “History of Lynching,” NAACP. No date.

- No author, “The Medgar Evers Assassination,” PBS Newshour. April 18, 2002.

- No author, “Murders in Mississippi,” PBS American Experience. No date. Stephen Smith, “’Mississippi Burning’ Murders Resonate 50 Years Later,” CBS News. June 20, 2014.

- David Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy. New York: Grove Press, 2020.

- Anthony Nocella, II, Priya Parmar, and David Stovall, editors, From Education to Incarceration: Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline. Second edition. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2018. Monique Morris, Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. New York: New Press, 2015. Christopher A. Mallett, The School to Prison Pipeline: A Comprehensive Assessment. New York: Springer Publishing, 2015.

- Mychal Denzel Smith, “Why Aiyana Jones Matters,” The Nation. June 19, 2013.

- Michael Siegel, et al., “The Relationship Between Structural Racism and Black-White Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings at the State Level,” Journal of the National Medical Association. April, 2018. Pages 106-116.

- Charles C. Mann, “1491,” The Atlantic. March, 2002.

- Text of the Removal Act, dated May 28, 1830. Mount Holyoke College.

- Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014. Pages 110-114. Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1492-Present. New York: Harper Collins, 2003. Pages 137-142.

- William M. Osborne, The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During the American-Indian War from Jamestown Colony to Wounded Knee. New York: Random House, 2000. Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the Californian Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. Yale: Yale University Press, 2016.

- Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014. Pages 137-38. Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1970. Pages 83-94.

- Brigham D. Madsen, The Shoshoni Frontier and the Bear River Massacre. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1985. Estimate of 265 women and children killed is on pages 189-190. Deseret Newsreporter quote on page 194.

- Terry L. Anderson and Peter J. Hill, The Not So Wild, Wild West: Property Rights on the Frontier. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004.

- National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1995. Ward Churchill, Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 2004.

- Abraham Lincoln, State of the Union Address. December 3, 1861. PresidentialRhetoric.com.

- James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. Pages 202-203.

- Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1492-Present. New York: Harper Collins, 2003. Pages 354-357. Scott Martelle, Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

- Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Wolfe Marks, It Didn’t Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States. New York: W. W. Norton, 2001. Page 244.

- Michael Sainato, “’It’s Because We Were Union Members’: Boeing Fires Workers Who Organized.” The Guardian. May 3, 2019. David Welch, “GM Squeezed $118 Million From Its Ohio Workers, Then Closed the Plant,” Forbes. March 29, 2019.

- Luke Darby, “Is Your Employer Stealing From You?” GQ. November 8, 2019.

- Sky Palma, “Viral Screenshot of Jim Cramer’s ‘Mad Money’ Shows ‘Everything That’s Wrong With America,’” Rawstory. April 13, 2020.

- Soheil Saneei, “Worker Cooperatives Popular, Will Move America Forward,” Democracy at Work. December 5, 2018. Michelle Chen, “Worker Cooperatives are More Productive Than Normal Corporations,” The Nation. March 28, 2016.

- CBS News, “Cesar Sayoc, Package Bomb Suspect, is a Florida Trump Supporter,” October 27, 2018. Jose Paglieri, “Suspect in Congressional Shooting was Bernie Sanders Supporter, Strongly Anti-Trump.” CNN. June 15, 2017.

Media Attributions

- KKK © Denver News is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sand Creek © Denver Public Library is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frank Little © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license