Chapter 46: Strategies of Organized Interests

“Today, most lobbyists are engaged in a system of bribery but it’s the legal kind, the kind that runs rampant in the corridors of Washington. It’s a system of sycophantic elected leaders expecting a campaign cash flow, and in return, industry, interest groups, and big labor are rewarded with what they want: legislation and rules that favor their constituencies.”

—Jimmy Williams (1)

Lobbying

All organized interests try to further their members’ political interests. They choose among myriad strategies, the most obvious being lobbying. Lobbying takes its name from the centuries-old British House of Commons tradition where constituents petition their member of Parliament (MP) in the building’s lobby. Since lobbyists cannot participate directly in work on the House or Senate floor, they interact—figuratively speaking—with Representatives and Senators in the Capitol building’s lobbies. Lobbying refers to efforts to persuade legislators and executive branch officials to make decisions that favor a particular set of interests over others. In Congress, lobbyists might testify before standing committees on legislation, ply congressmen and their staff with research and other information that favors their point of view, provide congressmen and their staff with draft legislation, or invite congressmen and their staff to events sponsored by the industry or interest they represent. Lobbyists also interact with executive branch officials, providing them with information and language in the rule-making process. Because of the revolving-door phenomenon, lobbyists are often former congressional members, former congressional staff, or former executive branch officials.

Campaign Financing

Another prominent strategy for organized interests is to donate money to political campaigns. They form political action committees—known as PACs—which must be registered with the Federal Election Commission. The PACs donate money to political candidates who are likely to support the group’s interests. Very often lobbyists concentrate on the incumbent congressional members who sit on the standing committees that write legislation on their key issues or who oversee the executive agencies they deal with most often. And the sums of money are significant. In the 2024 election cycle, PACs in the finance, real estate, and insurance sector contributed over $82 million to political candidates across the country; PACs in the healthcare sector contributed almost $52 million; and organized labor PACs contributed more than $55 million. (2)

What do the organized interests get for their money? Critics of America’s campaign finance system argue that if such contributions are not actually buying votes, which would be very hard to prove absent some smoking gun document linking the campaign cash and the vote in a quid pro quo arrangement, they are certainly buying access. That is, these groups’ lobbyists are likely to have the kind of close contact with congressional members and their staff that would not be afforded to other groups that had not donated. Organized interests have complained that they aren’t pressuring the politicians for votes, but that politicians are shaking them down for campaign contributions. Rarely is the relationship between lobbying, campaign contributions, and access to politicians made explicit, but sometimes people slip up and let the cat out of the bag. For example, in 2018 Mick Mulvaney, head of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau—the agency designed to protect financial services consumers—and a former congressional member, said the following about his standard operating procedure: “We had a hierarchy in my office in Congress. If you’re a lobbyist who never gave us money, I didn’t talk to you. If you’re a lobbyist who gave us money, I might talk to you.” (3) He then added that if someone from his district came to D.C. and sat in his office lobby, he would talk to them regardless of financial contribution. Still, the implication is that of all the organized interests in Washington, he preferred to speak with those who contributed to his campaign war chest. Political science research confirms that money can buy access. In a neat experiment, Joshua Kalla and David Broockman, two Berkley graduate students, found that “Members of Congress were more than three times as likely to meet with individuals when their offices were informed the attendees were donors,” and that said meetings were more likely to include senior staff if the individuals were donors. (4)

Going Public

Organized interests often use the going-public strategy to further their interests. This is a catch-all category of activities in which the group generates or demonstrates public support for its cause. Examples include mobilizing the grassroots, which is getting ordinary people or members of the group to write letters. This can be very effective if it is genuine. That is, if the interest group can really get thousands of people to call, write, or email their congressman all expressing one side of an issue, it tends to get legislators’ attention. This works with executive agencies as well. Before government agencies publish regulations in the Federal Register, they invite all interested persons to comment, and organized interests are in a favorable position to generate significant volumes of comments. Very often, though, the organized interest will fake a grassroots movement by generating thousands of emails or faxes that only look like they come from ordinary people. Senator Lloyd Bentsen coined the term astroturf lobbying to describe this behavior. (5) Narrow economic interests will often employ astroturf lobbying to make it seem like they are representing large numbers of people.

Another form of going public is to run an expensive marketing campaign involving commercials on radio and television as well as advertisements and newspaper editorials. Organized interests might also stage a march or demonstration to show decision makers how numerous and mobilized their members are. Civil rights groups staged the March on Washington in 1963, filling the National Mall with some 250,000 peaceful protesters. Famously, it was at that march that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. In the spring of 2006, nearly a million people all across the country marched in demonstrations against what they perceived to be harsh anti-immigrant legislation pending in Congress. (6) Another example was the 2017 Women’s March on Washington D.C the day after Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration. Beginning as a Facebook post by a Hawaiian grandmother the day after Trump was elected, it ballooned into what was referred to as “one of the largest and significant demonstrations for social justice in America’s . . . history.” The turnout of 500,000 people dwarfed the turnout for Trump’s inauguration itself, and altogether 2.6 million people marched in all fifty states and thirty-two countries. (7) The demonstrations in the middle of the 2020 pandemic highlighted the issue of police violence in the wake of cases like the police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville.

Litigation

Organized interests frequently use litigation—taking the matter to court—to achieve their ends in addition to lobbying the legislative and executive branches. This can be an expensive strategy but can pay off well if they prevail in court and set precedent in their favor. The organized interest can bring the lawsuit directly, or they can finance lawsuits brought by others, or file amicus curiae briefs in favor of one side in another case to which the organized interest is not a direct party. Civil rights groups, led by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, successfully pursued litigation to strike down discriminatory laws and practices. Environmental groups often sue to halt or modify large projects that they believe violate environmental laws such as the Endangered Species Act or regulations against development in wetlands. Conservative groups have successfully used state legislation combined with litigation to chip away at and eventually overturn Roe v. Wade (1973), the Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion.

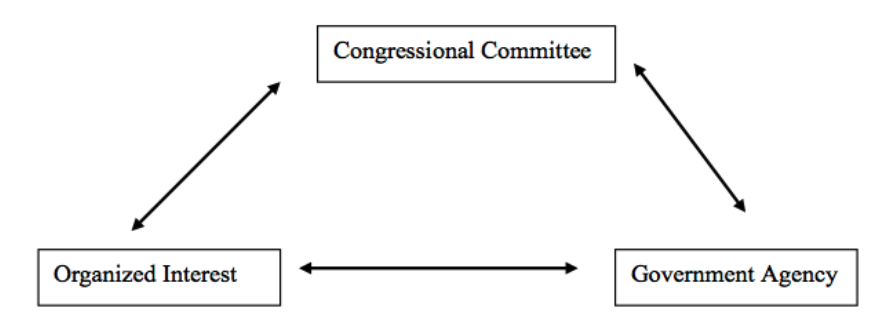

Iron Triangles

Iron triangles are not an organized-interest strategy. Rather, the term refers to the triangular relationship organized interests form with executive agencies and congressional decision makers. Political scientists refer to this mutually reinforcing relationship as an iron triangle, because it often seems impervious to outside influence. The triangle seems to operate as a sub-government unto itself. We can illustrate a generic iron triangle this way.

The double-arrowed lines in the diagram represent two-way supportive relationships. Let’s look at each point of the triangle.

The double-arrowed lines in the diagram represent two-way supportive relationships. Let’s look at each point of the triangle.

The organized interest provides campaign contributions to members of congressional standing committees that deal with the organized interest’s issues and concerns. The organized interest also lobbies the government agency and may even provide the governing agency vital information it needs to do its job. This is the case with defense contractors and the Pentagon as well as pharmaceutical companies and the Food and Drug Administration. Through revolving doors, organized interests provide safe and lucrative landing spots for former congressional members and their staff and executive branch officials.

The government agency administers the programs or writes the regulations that the organized interest depends on. For example, if the Pentagon doesn’t purchase a new submarine, the company that makes submarines loses business. If the Food and Drug Administration writes overly stringent safety regulations for new drugs, pharmaceutical companies are going to have difficulty bringing new drugs to market. Also, government agency programs can provide important benefits to the relevant congressional committee members. For example, if the Pentagon does build the submarine, that means creating many jobs in the districts those congressmen represent. Agriculture Department subsidies tend to benefit congressional agriculture committee constituents.

Finally, the congressional committee is in a position to act favorably on legislation that benefits organized interests. If the committee decides to build the new submarine, the company that makes it will benefit. If the committee decides to fund subsidies for a certain crop, the crop growers will benefit. It also provides a budget and oversight to the government agency in question. If the committee were to reduce agency funding, the agency would lose power and prestige.

You can see how iron triangles are mutually reinforcing and tend to continue the status quo despite repeated calls to reduce government’s size. Pick an area of public policy and see if you can identify the key players and their relationship in an iron triangle.

References

- Jimmy Williams, “I Was a Lobbyist for More Than 6 Years. I Quit. My Conscience Couldn’t Take It Anymore,” Vox. January 5, 2018. Emphasis in the original.

- Opensecrets.org.

- David A. Graham, “Mick Mulvaney Says the Quiet Part Out Loud,” The Atlantic. April 25, 2018.

- Joshua L. Kalla and David E. Broockman, “Campaign Contributions Facilitate Access to Congressional Officials: A Randomized Field Experiment,” American Journal of Political Science. July 2016. Pages 545-558.

- Peter Grier, “The Time-Honored Practice of Astroturf Lobbying,” The Christian Science Monitor. September 3, 2009.

- Mark Engler and Paul Engler, “The Massive Immigration-Rights Protests of 2006 are Still Changing Politics,” Los Angeles Times. March 4, 2016.

- Heidi M. Przybyla and Fredreka Schouten, “At 2.6 Million Strong, Women’s Marches Crush Expectations,” USA Today. January 22, 2017.

Media Attributions

- Lobbying © clif 1066 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Iron Triangles © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license