Chapter 42: The Historical Development of American Political Parties

“Americans want a politics they don’t have to hate. And therein lies our hope: Democracies are uniquely open to change, and if citizens want politicians to move beyond false choices, it is in their power to demand it.”

–E. J. Dionne, Jr. (1)

Political parties started early in the American republic, despite the fact that many founders—in theory, if not in practice—disparaged the factionalism and corrosive influence of political parties. In his farewell address, President George Washington warned against political parties, particularly those based on geographic loyalties. He went on to say that partisanship “serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another; foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passion.” (2) Nevertheless, political parties became entrenched in the political system.

In a survey course such as the one you are taking, there really isn’t time to go into the full scope of American party development, but you should be familiar with several important developments in the history of the American party system. One thing you should note is that, ideologically speaking, American political parties resemble tectonic plates on the earth’s surface that don’t stay firmly put in one place. Conservatism and progressivism have at various times found homes in different political parties.

Beginnings of the Party System

Party struggles really began within the Washington administration itself, personified by the political differences between his Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, and his Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson believed in a less energetic central government than did Hamilton—at least until Jefferson became president later and carried through the Louisiana Purchase without getting clear congressional authority. Hamilton pushed for the United States to develop its manufacturing sector and become a commercial power, while Jefferson envisioned a secure republic made by yeomen farmers with small landholdings. Jeffersonians formed the Democratic-Republican party, explicitly aiming to invoke the Revolution’s egalitarian principles, while the Hamiltonians formed the Federalist party to remind people of the Constitution’s triumphal plan. (3) It is somewhat ironic that Jefferson had a hand in founding a political party, because he shared Washington’s antipathy for them. He said, “If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.” (4) And James Madison similarly warned against the evils of faction in Federalist #10. Despite that, the Democratic-Republican party coalesced around Jefferson and Madison. The Federalists initially had the upper hand in early party competition, selecting John Adams to replace Washington in 1797. But the Democratic-Republicans came charging back with Jefferson’s two-term administration beginning in 1801, James Madison’s two terms, and James Monroe’s two terms ending in 1825. The Federalists quickly faded from the scene.

Democrats and Whigs in the Antebellum Period

With the Federalists fading, the Democratic-Republicans were the only game in town, but then they disagreed among themselves in the 1820s and formed two discrete parties: the Democrats, which have continued to the present day, and the National Republicans, which then became the Whig Party that eventually dissolved over slavery in the 1850s. Meanwhile, back to the 1830s and 40s: The Democratic Party was the dominant one, electing Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, James Polk, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan between 1828 and the beginning of the Civil War. The Whigs managed to elect two ill-fated presidents. The first was William Harrison, who delivered a long inaugural address on a cold and windy day and died of pneumonia about a month into his presidency. (5) Zachary Taylor was the other Whig elected president. After taking office in 1849, he died of acute gastroenteritis sixteen months later. (6) The interesting thing about the antebellum national party system was that it was the Whigs, not the Democrats, who believed in using the central government’s power to make “internal improvements” to the country such as roads and canals. The Democrats were the party of the “common man,” which is still its reputation, but the Democratic party then was also openly hostile to Blacks, whether slave or free. John C. Calhoun, a prominent Democrat from South Carolina who at times served as a representative, a vice president, and senator, once lamented that the phrase in the Declaration of Independence that all men were created equal “has become the most false and dangerous of all political errors. . . We now begin to experience the danger of admitting so great an error to have a place in the declaration of independence.” (7)

The Civil War Crisis

The American party system was rocked by the crisis over slavery and states’ rights that resulted in the Civil War. The Whig party split into a Northern wing that held on to the principles of an active central government, and a Southern wing whose members were concerned that a central government powerful enough to make “internal improvements” was powerful enough to end slavery. The Democrats were split between North and South as well, but that party survived whereas the Whig party completely disintegrated. In the mid-1850s, northern Whigs joined some antislavery Democrats and members of the antislavery Free Soil Party to create the modern Republican Party.

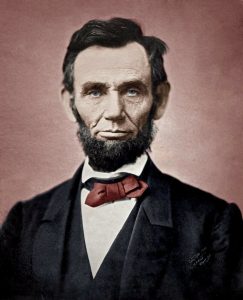

Historian Heather Cox Richardson reminds us that the early Republican Party opposed great wealth accumulation, promoted land distribution, the equal rights of immigrants, and government promotion of a transcontinental railroad. Many early Republicans were so progressive that they were referred to as Red Republicans. Were you ever taught that in school? Neither was I. Pledged to fight the “twin relics of barbarism”—slavery and polygamy—early Republicans were mobilized when the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed, which overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and allowed new territories to permit slavery if they wanted. Early Republicans had a vision of America as a land free not only from slavery, but from wage slavery as well—meaning the business exploitation of for-hire laborers. They celebrated autonomous workers—primarily independent farmers and the self-employed—and feared the power of capitalists, regardless of whether they were plantation owners in the South or factory owners in the North. Alvan Bovay was one of the people who initiated the push to establish the Republican Party in 1854. He is credited with naming it “republican” to hearken back to the views of Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson. He worked on a number of radical causes, including a “vote yourself a farm” campaign, and wrote for George Evans’ Working Man’s Advocate and Young America newspapers. Abraham Lincoln, the Republican’s second presidential candidate, won the very divided election of 1860 with only 40 percent of the popular vote. The land reform that Bovay and Evans advocated in the 1850s was pushed by Lincoln and became the Homestead Act of 1862, which distributed land in the West to settlers who would “improve” it. (8) With the demise of the Whig Party over the slavery issue, the Republicans and Democrats became the pre-eminent political parties in American politics to this day.

Republican Dominance

The era from the Civil War to the Gilded Age was one in which the Republicans dominated the presidency—they elected twelve of fifteen presidents from 1860 to 1929—and often enjoyed Republican majorities in the House and Senate as well. The Republicans dropped any hint of “red republicanism” and evolved into a party that promoted business interests and economic growth, pushed public schools that produced the standardized graduates that business leaders needed, endorsed the gold standard that promoted price stability that business leaders wanted, and supported high tariffs on imports that protected U.S. manufacturers. It was during this period of Republican dominance that wealth and income inequality grew to obscene levels that were fueled by monopoly capitalism. The Democrats maintained a stronghold in the South and strong support among Northern-city Catholic immigrants and small Mid-western farm owners. Later, the South became known as the Solid South because Democrats dominated there until after the mid-1960s when Republicans began to rise. Populism gripped the Democratic Party in the late 1890s and it looked like they might break Republican dominance, but in the election of 1896, the Republicans’ huge financial advantage and victories in the Electoral College-rich Northeastern states kept the Democrats out of the White House. The spirit of progressivism infected both parties in the early 1900s, but it created the most lasting impression in the Democratic Party. In the 1912 election when Republicans split between William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson became president, and the Democrats began to embrace many progressive ideals—using government to solve social problems, controlling the power of large business interests, and instituting social reforms such as extending the right to vote and banning child labor. However, the Democratic Party remained a bastion of racism, particularly in the South.

The New Deal Coalition

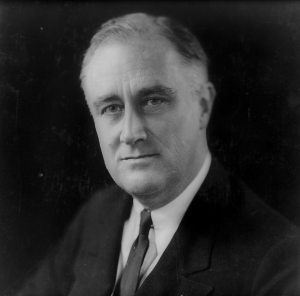

The period from the 1930s to the 1960s was a period of Democratic party ascendance. The Great Depression began with the stock market crash in October 1929 and marked the death-knell for Republican’s long-held dominance of national politics. Many people came to the conclusion that reckless pro-business Republican policies of the 1920s caused the Depression, and also were convinced that President Herbert Hoover’s conservative response to the crisis was insufficient. The 1932 election brought Democrat Franklin Roosevelt to power–the only president to win election four times–and his administration used government’s power to alleviate suffering, regulate the economy, and put people back to work. The overall policy, known as the New Deal, included such features as Social Security, unemployment insurance, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Works Progress Administration, among many others. The Democrats dominated national politics from 1933 to the end of the 1960s, largely because of what has become known as the New Deal Coalition. They cobbled together a coalition of unionized workers, farmers, Jews, white-collar professionals, African-Americans, and urban immigrants who were predominantly Catholics. The New Deal programs were popular enough that the Republican Eisenhower administration left them in place in the 1950s, and the Democratic Johnson administration built on them somewhat in the 1960s.

Contemporary Party Struggles

Things can change rather quickly in politics, but we can make the following observations about the contemporary party system. The first thing to note is the demise of the New Deal Coalition. The success of the Civil Rights Movement, the cultural turmoil of the late 1960s, and the stridency of the Democratic party’s anti-Vietnam War wing fractured the New Deal coalition and hurt many Democratic candidates’ electoral chances. The New Deal coalition had been built upon the economic interests of the common man regardless of race or religion. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, however, the Republicans became increasingly successful in attracting support from Whites opposed to racial desegregation, from men and women who were disconcerted by women’s liberation, from rural voters concerned about gun control, and from voters who disdained the perception of pacifism in American foreign policy. Moreover, the Roe v. Wade (1973) decision legalizing abortion and the rise of the gay rights debate handed Republicans two social issues that were instrumental in courting Catholics, evangelical Protestants, and Mormons.

Beginning in the 1960s, Republicans pursued what most people call the Southern Strategy—a conscious and largely successful attempt to capture the South by playing on White’s fears of the Civil Rights movement. The Southern Strategy was really a broader strategy linking the South with suburban and rural areas across the United States, aimed at White fears of racial integration, urban crime, and economic insecurity. In a 1981 interview, Republican strategist Lee Atwater explained that the Southern Strategy rested on stressing race without overtly mentioning it:

You start out in 1954 by saying, “Nigger, nigger, nigger.” By 1968 you can’t say “nigger”—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.… “We want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than “Nigger, nigger.” (9)

The Republican party also embraced an assault on public schools—relabeled in their vocabulary as “government schools”—at the behest of religious conservatives opposed to school integration and the teaching of evolution. The Southern Strategy was successful. The Democrat’s Solid South transformed to become a bastion of Republican office holders instead. Republicans won all but one presidential election from 1968 to 1992, won eight of the thirteen presidential elections from 1968 to 2016, and wrested both congressional chambers from Democrats control. Similarly, Republicans dominated state gubernatorial and legislative elections in 2010, which allowed them to gerrymander district boundary lines to their advantage following the 2010 census. (10) Even when outsider Donald Trump captured the Republican presidential nomination in 2016 against the wishes of party leadership, the Republicans were able to win the White House again with help from the Electoral College even when their candidate lost the popular vote that year. In 2020, President Trump lost his bid for reelection, but the Republican Party maintained control over the majority of state legislatures and regained control of the House of Representatives. Donald Trump won the presidency in 2024, and the Republicans captured both chambers of Congress.

Meanwhile, the Democratic party hewed sharply to the right in the late 1970s in order to compete with the Republicans. The Democrats increasingly turned to the same sources as the Republicans to fund their candidates—corporations and the wealthy—and it pursued policies that were often indistinguishable from the Republicans. Bill and Hillary Clinton led the way in this transformation, aggressively courting Wall Street and corporate money and supporting anti-welfare, pro-finance, tough-on-crime policies designed to win back voters that the party had lost to Republicans. Still socially liberal, the Democratic party became controlled by the New Democrats, who can more properly be called the Corporate Democrats because of their connections with and deference to large corporations. (11)

President Obama was solidly in the corporate wing of the Democratic party, and his policies were described by one astute political observer as “crafted by representatives of corporate/financial America, who happen to entirely make up his inner circle.” (12) This was particularly true of Obama’s tepid response to the Great Recession that was caused by Wall Street’s predatory behavior, but also manifested itself in the very corporate friendly Affordable Care Act. (13) Progressive members of the Democratic Party had no place to go until democratic-socialist Bernie Sanders reignited their hopes in his failed attempt to gain the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016. Sanders’ candidacy in 2016 and again in 2018 underscored the deep divisions in the Democratic party between its corporate and progressive wings. In 2020 the Democrats nominated Joe Biden as their presidential candidate, a veteran politician solidly in the corporate wing of the party. Once elected, Biden packed his cabinet with corporate leaning politicians and bureaucrats. In July of 2024, Biden withdrew from running and endorsed Kamala Harris, his vice president, and the party nominated her the next month. She lost.

References

- E. J. Dionne, Jr., Why Americans Hate Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991. Page 373.

- George Washington, Farewell Address, September 19, 1796. The National Archives.

- Actually, early on Jeffersonians simply called themselves the Republicans before they were called the Democratic-Republicans, and then the Democrats. To avoid confusion with the later and unrelated Republican Party, political scientists usually extend the Democratic-Republican name back in time to encompass Jefferson’s Republicans.

- Paul Johnson, A History of the American People. New York: HarperCollins, 1997. Page. 216.

- He was replaced by John Tyler.

- He was replaced by Millard Fillmore.

- Mackubin T. Owens, “The Democratic Party’s Legacy of Racism,” a publication of the Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs at Ashland University. December 2002.

- For the progressivism of the early Republican party, see the following: John Nichols, The “S” Word. A Short History of an American Tradition…Socialism. 2nd edition. New York: Verso, 2015. Chapters 2 and 3. Heather Cox Richardson, To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party. New York: Basic Books, 2014. Pages 1-45.

- Rick Perlstein, “Exclusive: Lee Atwater’s Infamous 1981 Interview on the Southern Strategy,” The Nation. November 13, 2012.

- Vann R. Newkirk II, “How Redistricting Became a Technological Arms Race,” The Atlantic. October 28, 2017.

- Lance Selfa, The Democrats: A Critical History. Revised and Updated Edition. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008. Pages 63-85.

- Matt Taibbi, “Obama and Jobs: Why I Don’t Believe Him Anymore,” Common Dreams. September 6, 2011.

- Michael Lewis, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010. Matt Taibbi, Griftopia: A Story of Bankers, Politicians, and the Most Audacious Power Grab in American History. New York: Random House, 2010.

Media Attributions

- Lincoln © casually cruel is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Roosevelt © Executive Office of the President is licensed under a Public Domain license