Chapter 32: Paths to the Supreme Court

“The judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”

–U.S. Constitution, Article III

Federalism in America’s Court System

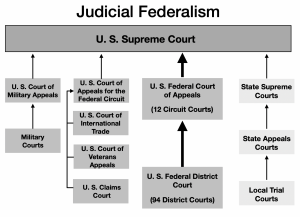

Since the United States is a large federal republic, it has a fairly complicated court system. The phrase judicial federalism refers to the dual court systems—federal and state—operating in the United States. State courts handle most United States’ criminal and civil cases, while federal courts handle federal criminal and civil statutes, regulations, and constitutional provisions. Below is a simplified diagram of judicial federalism.

Paths to the Supreme Court

Let’s flesh out three important things about the diagram. First, note that the three boxes on the right represent the state court system where most U.S. cases occur—e.g., people on trial for murder, rape, robbery, burglary, embezzlement, fraud, civil lawsuits, and so on. Cases can go straight through the state court system and on to the Supreme Court, but that is not a common path. The diagram is a little bit deceptive in this sense: the lightly shaded boxes on the right represent a large amount of work overall but represent a comparatively smaller source of Supreme Court cases.

Second, note the diagram’s two boxes in the middle with thick arrows. Most Supreme Court cases come up through the federal district courts and then through one of the twelve federal circuit courts of appeals. Other federal cases such as military cases and trade cases, etc. have their own paths, but again, the main route is depicted with the thick arrows.

The third thing we should note is that cases handled in state courts can sometimes raise questions that need to be adjudicated in federal courts. If a state defendant has exhausted their state options, they may seek a writ of habeus corpus from a federal court. Habeus corpus literally means “you have the body,” and refers to the court ordering state or federal authorities to bring a detained person to the court and show cause for the detention or incarceration. Obviously, the person is hoping the court will release them because of some violation of their federal rights. For example, the defendant may argue that their Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure were violated, or perhaps their Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment due process protections were violated.

Supreme Court Jurisdiction

The paths to the Supreme Court are conditioned by its jurisdiction. Jurisdiction refers to the scope or mandate of a court. What kinds of cases can it hear, and how does it hear them? The Supreme Court has the broadest jurisdiction of any federal court, but its mandate is divided into its original and appellate jurisdictions. Original jurisdiction refers to those cases that are heard first in the Supreme Court. According to Article III of the Constitution and federal statute, the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction in the following kinds of cases:

- Controversies between states.

- All actions or proceedings to which ambassadors, other public ministers, consuls, or vice consuls of foreign states are parties.

- All controversies between the United States and a state.

- All actions or proceedings by a state against the citizens of another state or against aliens. (1)

The Supreme Court must take these cases when they arise but will often appoint a “special master” to hear the dispute and recommend a solution. Original jurisdiction cases are rare, but when they do occur, the Supreme Court behaves more like a trial court, collecting evidence, hearing testimony, and establishing facts.

The Supreme Court’s second jurisdiction is its appellate jurisdiction—that is, cases on appeal from lower federal or state courts. Most of the Supreme Court’s caseload falls here. When exercising its appellate jurisdiction, the Supreme Court does not act like a trial court, but instead reviews lower court rulings and either upholds them as correct or reverses them. The Court is under no obligation to take cases on appeal. Every year, thousands of cases land on the Supreme Court’s doorstep, of which typically less than 100 are argued before the justices. The rest are denied cert, or the justices decided without plenary review. Within the court’s appellate jurisdiction there is a split between those cases that work their way through the federal courts and those that began in state courts. In a given year, about two-thirds of the Supreme Court’s caseload comes on appeal through the federal courts, and about one-third comes from state courts, with few to no original jurisdiction cases.

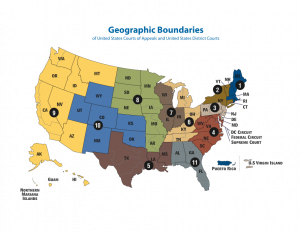

The federal court system’s lowest rung is composed of the ninety-four federal district courts. For the less populous states like Utah, the federal district court’s jurisdictional boundaries follow the state boundaries. Large states contain several district courts within their boundaries. Federal district courts are trial courts in cases involving federal criminal statutes, applicable civil lawsuits, and suits against federal agencies. Usually, one federal judge presides over each case at the district court level. Hundreds of thousands of criminal and civil cases are initiated in federal district courts around the country, most of which never make it to trial. (2)

The district courts are grouped into twelve circuit courts of appeal, plus there is a court of appeals for the federal circuit that handles appeals from the U.S. Claims Court, the U.S. Court of International Trade, and other national-level courts. As you can see in the map, (3) cases arising out of federal district courts in Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas, and Oklahoma are appealed to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, located in Denver, Colorado. There, a panel of three judges hear cases. The circuit courts are appellate courts—judges review the district courts’ decisions rather than develop new evidence or testimony. They are called “circuit” courts, by the way, because in earlier times, judges literally rode circuit via horseback or stage to remote areas to hear court appeals.

References

- Article III of the Constitution and the Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute.

- Specific caseloads can be found at the U.S. Courts website.

- Map taken from the websiteof the Federal Bar Association.

Media Attributions

- Judicial Federalism © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Court Boundaries © Federal Bar Association is licensed under a Public Domain license