Chapter 14: The Battle for Ratification and the Bill of Rights

“The Bill of Rights we have is…different in many ways from the one the Constitution’s critics wanted. It says nothing about ‘no taxation without representation’ and ‘no standing armies in time of peace.’”

—Pauline Maier (1)

“No free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.”

–Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776

Nine States to Ratify

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention finished their work on September 17, 1787. Knowing that neither the Congress nor the state legislatures would approve the new Constitution, they created a ratification process in which each state would hold a special convention on the Constitution. The delegates agreed that if nine out of the thirteen states voted to ratify, that would be sufficient to implement the Constitution. The new Constitution was presented to Congress. But first, Congress debated for two days whether to censure the delegates for having gone beyond their mandate. Congress chose not to censure, instead, it directed state legislatures to hold elections for state ratifying conventions, as called for in Article VII of the new document.

The period from 1787 to 1790 was a unique one in world political history because the people of the United States engaged in a serious debate about the best form of government for a free people. Delaware was the first state to ratify the Constitution on December 7, 1787. Rhode Island initially rejected the Constitution in a popular referendum in March of 1788. New Hampshire became the necessary ninth state to ratify the Constitution in June of that year, but it was vitally important that the large states of New York and Virginia join the project. They both narrowly did so later that summer. North Carolina ratified the Constitution after Congress proposed a Bill of Rights in 1789, and Rhode Island held a ratifying convention in 1790 to unanimously approve the new government.

Federalists and Anti-Federalists

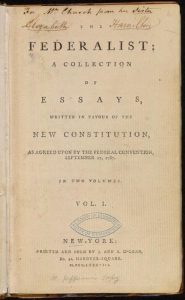

Those who supported the Constitution called themselves Federalists, while opponents have come to be known as Anti-Federalists—although that was a label put on them. It was a bitter and acrimonious debate. Their arguments took the form of newspaper editorials, pamphlets, letters, disagreements in pubs and churches, and debates at ratification conventions. The most famous documents in this debate came out of New York, where Alexander Hamilton recruited James Madison and John Jay to help him write a series of eighty-five essays from 1787 into 1788 in favor of the Constitution. These essays, published serially in newspapers under the pseudonym Publius, have since been published together as the Federalist Papers. They do constitute a brilliant defense of the Constitution, but keep in mind that many Federalists in other parts of the country were also writing their own works, and the Federalist Papers didn’t achieve their fame and influence until well after the Battle for Ratification was over. (2)

We tend to forget that many prominent people opposed the Constitution, including Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee, George Mason, Robert Yates, Patrick Henry, Elbridge Gerry, Edmund Randolph, James Monroe, and George Clinton. The Anti-Federalists worried that the new government would be too powerful, resulting in a tyranny the states would be powerless to stop. (3) The Anti-Federalists had a large list of Constitutional features to which they objected. They saw the “necessary and proper” clause as giving the central government too much power. They saw the vice president as giving too much power to the state from which he hailed. They feared the president’s pardon power. They were suspicious of the president and the Senate’s ability to coordinate together to negotiate and ratify treaties that might damage particular states or regions because neither were elected by the people. They feared the supremacy clause.

The Anti-Federalists supported stronger state governments and a weaker national one because they feared that a national government would become tyrannical. An anonymous Anti-Federalist writing in the Virginia press under the name Philanthropus concluded that “The new constitution in its present form is calculated to produce despotism, thraldom [a state of subjugation or bondage] and confusion, and if the United States do swallow it, they will find it a bolus [drug], that will create convulsions to their utmost extremities.” (4)

The Bill of Rights

Even though they ultimately lost the argument, and the Constitution was ratified, the Anti-Federalists made an important contribution by stressing the Constitution’s major deficit: it lacked a Bill of Rights to protect the people. It is clear that their agitation in the ratifying conventions contributed to winning the argument to add a list of rights to the Constitution. (5) Interestingly, the Bill of Rights is said to have been fathered by two men—one Federalist and one Anti-Federalist. Anti-Federalist George Mason is sometimes called the father of the Bill of Rights because he wrote the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776 and constantly criticized the U.S. Constitution for omitting this important feature. In his “Objections to the Constitution,” published on November 19, 1787, in the Virginia Journal and the Alexandria Advertiser, Mason decried the fact that “there is no declaration of rights,” and that the federal government’s supremacy over the states would mean that “the declarations of rights in the separate States are no security” for the people’s freedom. He was not the only Anti-Federalist to protest the lack of a Bill of Rights. After the Pennsylvania convention approved the Constitution, twenty-one delegates who voted against it published a dissent in the Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser, December 18, 1787, arguing that the “omission of a Bill of Rights” jeopardized “those unalienable and personal rights of men, without the full, free, and secure enjoyment of which there can be no liberty.” (6)

Largely as a result of pressure in several ratifying conventions, the Federalists promised to add a Bill of Rights to the Constitution. Rhode Island and North Carolina even refused to approve the Constitution until they saw the Bill of Rights in place. Federalist James Madison is considered to be the second father of the Bill of Rights. He came reluctantly to the task, because he originally thought such a listing of liberties was unnecessary—he called them “parchment barriers” to government tyranny in a letter to Thomas Jefferson. (7) Nevertheless, when he ran for Congress, he promised his constituents that he would support a Bill of Rights, and he came to realize that adding the Bill of Rights was the best way to tamp down opposition to the Constitution. Madison originally wanted to weave the various protections into the language of the Constitution, but Congress instead decided to add them to the end of the document. (8) On September 25, 1789, the first Congress under the new Constitution jointly resolved to consider adding twelve amendments in the Bill of Rights.

All twelve amendments passed Congress, but the states only ratified ten by 1791. The two amendments that weren’t ratified at that time sought to prevent establishing a political aristocracy—a key Anti-Federalist concern—and aimed to better connect the national legislators with the people. One amendment said that Congress can vote to raise its pay, but the raise doesn’t take effect until after an election. It was finally ratified in 1992 as the Twenty-seventh Amendment. The other was a rather complicated amendment that attempted to keep the number of Congressional representatives in proportion to the number of state residents. It fell one state short of ratification. (9)

Source Material for the Bill of Rights

What were the sources of the Bill of Rights? That’s a good question. Some of the sources for the Bill of Rights were proximate to the time period when it was written, but others pre-date the document by hundreds of years. The American Bill of Rights clearly is a great, great, great—many times removed—grandchild of similar historical British assertions of rights. We can go back to the Magna Carta Libertatum—the Great Charter of Liberties, or Simply the Magna Carta—a settlement in 1215 between England’s King John and his barons. The Magna Carta was not a statement of liberties for ordinary people, but it was nevertheless historically significant for firmly establishing due process for free men. In all, four specific rights in the American Bill of Rights can be traced to the Magna Carta: due process, jury trials, prohibiting unlawful seizures, and prohibiting excessive fines.

Additionally, in the 1628 Petition of Right against Charles I, Parliament prohibited quartering soldiers in civilian households against the civilian’s will. The English Bill of Rights of 1689—a document forced upon William and Mary as they were invited to replace James II after the Glorious Revolution—first addressed the right of subjects to petition the King and stated that “Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law.” In all, seven specific protections in the U.S. Bill of Rights trace their heritage to English precedents. The majority of the Bill of Rights language—free speech, free exercise of religion, prohibitions against illegal searches, freedom of assembly, the right to counsel, etc.—came from the American colonial context. There are two possible sources to note: delegates at state ratifying conventions proposed amendments and assertions of rights that had already been written into state constitutions. The assertions of rights were particularly important. As political theorist Donald Lutz has clearly documented, “The states’ constitutions and their respective bills of rights, not the amendments proposed by state ratifying conventions, are the immediate source from which Madison derived what became the U.S. Bill of Rights.” (10) Interestingly, in those early state constitutions, the assertions of rights were included as prefaces that began those documents, whereas the U. S. Bill of Rights was appended at the end of the U. S. Constitution. For example, the Virginia state constitution of 1776 began this way: (11)

Virginia Declaration of Rights

I That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

II That all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people; that magistrates are their trustees and servants, and at all times amenable to them.

III That government is, or ought to be, instituted for the common benefit, protection, and security of the people, nation or community; of all the various modes and forms of government that is best, which is capable of producing the greatest degree of happiness and safety and is most effectually secured against the danger of maladministration; and that, whenever any government shall be found inadequate or contrary to these purposes, a majority of the community hath an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform, alter or abolish it, in such manner as shall be judged most conducive to the public weal.

IV That no man, or set of men, are entitled to exclusive or separate emoluments or privileges from the community, but in consideration of public services; which, not being descendible, neither ought the offices of magistrate, legislator, or judge be hereditary.

V That the legislative and executive powers of the state should be separate and distinct from the judicative; and, that the members of the two first may be restrained from oppression by feeling and participating the burthens of the people, they should, at fixed periods, be reduced to a private station, return into that body from which they were originally taken, and the vacancies be supplied by frequent, certain, and regular elections in which all, or any part of the former members, to be again eligible, or ineligible, as the laws shall direct.

VI That elections of members to serve as representatives of the people in assembly ought to be free; and that all men, having sufficient evidence of permanent common interest with, and attachment to, the community have the right of suffrage and cannot be taxed or deprived of their property for public uses without their own consent or that of their representatives so elected, nor bound by any law to which they have not, in like manner, assented, for the public good.

VII That all power of suspending laws, or the execution of laws, by any authority without consent of the representatives of the people is injurious to their rights and ought not to be exercised.

VIII That in all capital or criminal prosecutions a man hath a right to demand the cause and nature of his accusation to be confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence in his favor, and to a speedy trial by an impartial jury of his vicinage, without whose unanimous consent he cannot be found guilty, nor can he be compelled to give evidence against himself; that no man be deprived of his liberty except by the law of the land or the judgement of his peers.

IX That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed; nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

X That general warrants, whereby any officer or messenger may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of a fact committed, or to seize any person or persons not named, or whose offense is not particularly described and supported by evidence, are grievous and oppressive and ought not to be granted.

XI That in controversies respecting property and in suits between man and man, the ancient trial by jury is preferable to any other and ought to be held sacred.

XII That the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.

XIII That a well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defense of a free state; that standing armies, in time of peace, should be avoided as dangerous to liberty; and that, in all cases, the military should be under strict subordination to, and be governed by, the civil power.

XIV That the people have a right to uniform government; and therefore, that no government separate from, or independent of, the government of Virginia, ought to be erected or established within the limits thereof.

XV That no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.

XVI That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

–Adopted unanimously June 12, 1776 Virginia Convention of Delegates. Drafted by Mr. George Mason

Important Features of the Bill of Rights

We should highlight several features of the Bill of Rights. First, as noted above, unlike several state constitutions of the day, the federal Constitution does not begin with a declaration of rights. Instead, the first ten amendments—and subsequent amendments over the years—are grafted onto the end of the Constitution to modify or add to the original text. The next thing to note is how absolute the guarantees are in the Bill of Rights compared to its historical and contemporary antecedents. With respect to individual liberties, previous documents often used words like “ought” and “should.” For example, note how in the Virginia Declaration of Rights, the right to trial by jury “ought to be held sacred,” and excessive bail and cruel and unusual punishments “ought” not to be imposed. The Bill of Rights is much more direct and prohibitive, using language like “shall make no law” and “shall not be violated” and “shall be preserved.” In other words, the Bill of Rights went further than any previous document had in vigorously articulating individual liberties and freedom from an oppressive government. In that sense, the Bill of Rights is a ringing pronouncement that abstract concepts like natural rights have real meaning in our lives and that government needs to respect them.

Having said that, however, we should also note that the liberties enunciated in the Bill of Rights are not, in fact, absolute. It is fair to say that all these liberties are subject to legislation. A person cannot threaten to assassinate a political leader and hide behind the First Amendment’s freedom of speech. Your neighbors cannot start a toxic waste dump in their back yard and hide behind the Fifth Amendment’s property rights. A person’s right not to be searched does not protect them against lawfully issued warrants, and it does not protect them in situations where authorities do not have a warrant but have probable cause that a crime has been committed. You may not start a religion that sacrifices a virgin to your god on the summer solstice and claim that such an atrocity is ok because you are freely exercising your religion.

Here is the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments—passed by Congress, ratified by the states, and appended to the U. S. Constitution:

The Bill of Rights

Amendment I Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

References

- Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010. Page 467.

- Pauline Maier, Ratification. Pages 84-85.

- For a short, readable treatment of the Anti-Federalists, see Herbert J. Storing, What the Anti-Federalists Were For. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1981.

- Philanthropos, “Adoption of the Constitution Will Lead to Civil War,” The Virginia Journal and Alexandria Advertiser, December 6, 1787. Archived on the Constitution Society site at constitution.org.

- Carol Berkin, The Bill of Rights: The Fight to Secure America’s Liberties. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015. Gerard N. Magliocca, The Heart of the Constitution: How the Bill of Rights Became the Bill of Rights. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Pages 23-36.

- “The Address and Reasons of Dissent of the Minority of the Convention of Pennsylvania to their Constituents,” in Ralph Ketcham, editor, The Anti-Federalist Papers and the Constitutional Convention Debates. New York: New American Library, 1986. Page 247.

- James Madison to Thomas Jefferson on October 17,1788.

- Paul Finkelman, “James Madison and the Bill of Rights: A Reluctant Paternity.” The Supreme Court Review. 1990. Pages 301-347.

- Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights. New Haven: Yale University, 1998. Pages 3-19.

- Donald S. Lutz, “The State Constitutional Pedigree of the U. S. Bill of Rights.” Publius. 22(2): Spring, 1992. Page 29.

- The Avalon Project of The Yale Law School.

Media Attributions

- Federalist Papers © Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison is licensed under a Public Domain license