Chapter 11: Deism, the Indigenous Critique, Natural Rights, and the Declaration of Independence

“Nature is none other than God in things.”

“God…is everywhere in all things, not above, not outside, but present, not a being outside or above being, not a nature outside of nature, not a goodness outside of good.”

—Giordano Bruno [1548-1600] (1)

“Fix reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve of the homage of reason than that of blindfolded fear.”

—Thomas Jefferson (2)

Ideas are important—even if they initially appear strange and radical. The foundations of the current American political system originally came from ideas espoused by various seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European philosophers who thought deeply about the proper ordering of a political system. These philosophers, in turn, were (in part) responding to a critique of European societies by indigenous thinkers whose names have mostly been lost to history. Additionally, the ideas central to the American founding were grounded in philosophical understandings of matter, the universe, and God that the Christian church saw as heretical. As a student of American politics, it is important for you to have insight into the ideas and reasoning that shaped the Declaration of Independence and understand the following philosophical systems that helped shape American ideals. Let’s take this story in chronological order and start with the development of materialism into deism.

Deism

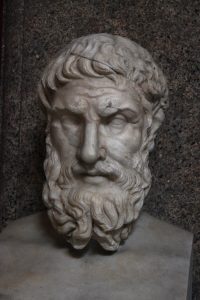

Materialism is a category of ancient Greek thinking that held that nothing exists except matter, its movements, and modifications—matter is all that there is in the universe. Matter is composed of atoms that have always existed. It cannot be destroyed but is continually transformed and recycled into different forms throughout an infinite universe. Democritus (c.460–c.370 BC) is most commonly referred to as an early proponent of philosophical atomism and materialism. Similarly, the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341-270 BCE) espoused atomism, materialism, and an understanding of the gods that differed from the established view. If you’ve ever read ancient Greek myths, you know that traditionally they thought of the gods as directly intervening in human existence—tricking people, fathering children with people, and so forth. Seeing the material universe as infinite, Epicurus understood the gods to be detached from the experiences of humans. He also taught that man can attain the greatest good and a tranquil state, free from fear and pain, through reasoned and virtuous action.

Why is materialism important? Materialism contrasts with Spiritualism, which is the belief that a spiritual realm exists and is distinct from matter. Spiritualists argue that the spiritual world governs the material and is essentially unknowable except through faith and revelation—which means that the material world does not really follow any laws that humans can discern through their own reason. Philosophical spiritualism forms the impetus behind all the Western religions, and it should be fairly clear that philosophical materialism necessarily challenges any religion predicated on revealed truth from the spiritual realm. Atheist and Deist approaches differ from Spiritualism, which sees a distinction between the material world and the spiritual one. People like Jefferson recoiled at that notion of spiritualism. Instead, they embraced secularism, Deism, and the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason.

An important step in the intellectual history of these ideas was the publication of On the Nature of Things in the first century BCE by Lucretius (99-55 BCE), a Roman poet and philosopher. Lucretius put forward familiar epicurean themes: The universe consists of matter and nothing else; the universe has no creator or designer, nor was it created for humans; humans have free will and can, through study, discern how the universe works; organized religions are superstitious and cruel delusions; the highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure (not hedonistic pleasure, but “real” pleasure) and the reduction of pain; the exercise of reason is accessible to everyone.

What does all this have to do with the American Declaration of Independence? The short answer is that during the centuries between Epicurus and Thomas Jefferson, materialism gave rise to Deism. You may have read that many—but certainly not all—of the American founders were Deists. Indeed, eighteenth century Deism strikes one as an updated version of Epicurus’ heretical understanding of the Greek gods. Deism is the belief in a supreme being or creator—Nature’s God—who does not intervene in the universe or interact with humankind, but who disappears into the natural rules that govern all matter. Just as Epicurus and Lucretius thought that the gods did not intervene in human affairs, Deists saw the Judeo-Christian-Islamic god as similarly removed from human experience—a state of affairs that requires humans to develop workable ethical and political codes themselves rather than receive them through revelation.

The American philosopher Matthew Stewart referred to this legacy when he coined the phrase Epicurus’s dangerous idea to refer to the notion attributed to Epicurus that talking about nature and talking about God are just two ways of talking about the same thing. This conclusion has tremendous theological and political implications. If the universe is infinite and has always existed, there is no role for an entity outside of matter and causation to play the role of a prime mover. No need for God in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic sense. Indeed, many people in the Epicurean-Lucretian tradition were persecuted and/or killed by Christian authorities for being atheists or for being Deists. Even the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza was banned from the Amsterdam synagogue in 1656 for this kind of naturalistic view of God. Note the references in the Declaration of Independence to “the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God” and to “their Creator.” (3) These all fit with a Deist’s understanding of the universe.

The Declaration of Independence was the political embodiment of the Epicurean-Lucretian philosophical tradition. When asked about his philosophy of life, Jefferson wrote that he was “an Epicurean.” Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things was one of his favorite books and he owned at leave five Latin editions of it. (4) The Declaration gave only a rhetorical nod to spiritualism, but a full-throated endorsement of reason marshalled to promote the common good and the general happiness of the American people.

The Indigenous Critique

The intellectual line from Epicurus’ materialism to Thomas Jefferson’s Deism is an important precondition for the ideas of the Declaration of Independence to flower in the late eighteenth century. Let’s talk about another important intellectual tradition—one with which you are probably even less familiar. First, a bit of history.

From 1534 to 1763, France explored and colonized what is now northeastern Canada and the American Great Lakes region. French colonial leaders and Jesuit missionaries had many conversations and debates with leaders from the Huron and Iroquoian nations around the Great Lakes and northeastern Canada. Some of these conversations took place in France, while most took place in the Americas. We have some notes of these conversations from the Jesuit missionaries. The most famous of these conversations was with a Wendat (Huron) statesman named Kandiaronk (1649-1701), a famed debater and orator who spoke in Paris and who also debated Hector de Callière, the Governor of Montreal, in the Americas. The Jesuit historian, Charlevoix, said no Native American he had met “ever possessed greater merit, a finer mind, more valor, prudence or discernment in understanding those with whom he had to deal.” (4) Much of what we know about Kandiaronk comes from the journals of Baron Louis-Armand Lahontan (1666-1716), which were published in 1703 as New Voyages to North America.

The Indigenous Critique refers to the stance of indigenous people like Kandiaronk—and others whose names are unfortunately lost to history—with respect to how best to organize a society and a political system. The Huron and Iroquoian intellectuals developed a sophisticated understanding of European society and did not like what they saw. They saw European society characterized by competitiveness, greed, selfishness, gross inequality, and hostility to true freedom. The Montagnais-Nskapi people of Labrador thought most French people were slaves because of their constant fear of violent punishment by their superiors. The Native Americans also noted the inequality of the sexes in Europe and the lack of sexual freedom.

Meanwhile, the Jesuit missionaries and the colonial leaders who gained an understanding of indigenous societies were similarly shocked. They could not understand the communitarian societies they encountered, replete with sexual freedom, relative equality of the sexes, leaders who gained their positions through respect rather than violence or inheritance, no incarceration for lawbreaking, no corporal punishment for children, and no real way for people to translate differences in individual wealth into political power. The indigenous people they encountered were vastly freer than almost all Europeans.

The contrasts between the freedom of indigenous people in North America and the lack of freedom in Europe was intellectually explosive. The anthropologist David Graeber and the archaeologist David Wengrow, in their book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, make a compelling case that the Indigenous Critique had a tremendous impact on what we call the European Enlightenment. It stimulated thoughts about “the state of nature” and the “natural rights” people might have had prior to mankind getting “stuck” with bureaucratic government, wage labor, despotic rulers, and economic and political hierarchies. (5)

Natural Rights

Let’s talk about the third intellectual tradition that comes together with Deism and the Indigenous Critique to form the basis for the Declaration of Independence. The Enlightenment overtook Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and constituted the intellectual fertilizer in which American independence grew. Responding to both the Indigenous Critique and Epicurus’ dangerous idea, Enlightenment thinkers argued that the laws of nature were subject to discovery, and the human condition could be improved through reason. In the area of political philosophy, people like Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and John Locke (1632-1704) were known as social contract theorists. They imagined how people might live in a state of nature that would allow mankind absolute freedom, where there is no authority to limit individual behavior. Not having seen indigenous societies for themselves, they envisioned the state of nature as essentially an anarchical condition in which there was no government, and thus no authority to limit individual behavior. While anarchy is appealing to some philosophers, it definitely was not to Hobbes and Locke. Hobbes argued in Leviathan that the state of nature would result in a war of all against all, and that people’s lives would be “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” He concluded that a strong state—the Leviathan—was necessary to provide order and at least a measure of freedom. (6) Locke did not have as pessimistic view, but he was worried that people would continually get into disputes with each other with no state or laws (as he understood them from his European point of view) to regulate conflicts. Another European philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), saw the state of nature as a paradise, but one that we can never get back to because civilization and property resulted in our downfall and resulted in us being “in chains.” Rousseau’s best hope for us was to construct a governing system in which “the general will” would prevail.

What these philosophers had in common was the idea that we could escape from the state of nature, with its unlimited freedoms that give rise to all sorts of conflicts, by setting up a government through a social contract, where the people agree to certain government-enforced restrictions on their liberties in exchange for a measure of security. Consequently, one is not entirely free in a civil society to do as one pleases with respect to others. George Washington put it eloquently in his letter transmitting the proposed Constitution to the Confederation Congress: “Individuals entering into society, must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest…. It is at all times difficult to draw with precision the line between those rights which must be surrendered, and those which may be reserved.” (7)

One way to draw the line to which Washington referred is to say that people retain their natural rights under the social contract. Natural rights are those rights that stem from the state of nature, and thus pre-date the government established by the social contract. Philosophers have tended to say that natural rights are granted by nature’s God, or by virtue of being born. The important thing to remember is that government does not give you your natural rights, as when it establishes a bill of rights. The bill of rights merely recognizes, and perhaps specifies, your preexisting natural rights. Locke’s classic statement of natural rights went as follows: “…the state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions: for men being the workmanship of one omnipotent, and infinitely wise maker…” (8)

A contemporary listing of natural rights follows Locke’s lead and includes equality, life, liberty, and property. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, acting as a scribe for the committee whose most vocal members were John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, substituted “pursuit of happiness” for “property,” which is an intriguing turn of phrase that appears to have its proximate origin in Locke and its ultimate origin in Epicurus. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke wrote that “the highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness,” and we know how closely Jefferson read Locke. We also know that Jefferson ascribed to Epicurean philosophy which—aside from its materialism—held that it is only through reasoned and virtuous action that man can achieve true happiness. Perhaps the immediate source of the Declaration’s reference to the pursuit of happiness was his colleague John Adams, who wrote in his Thoughts on Government (1776) that “the form of government which communicates ease, comfort, security, or, in one word, happiness, to the greatest number of persons, and in the greatest degree, is the best.”

Those who believed in natural rights came to a conclusion that frightened monarchs throughout Europe: that if government is not upholding the natural rights of citizens, and instead is consistently undermining them, the people are entirely justified in taking up arms against their rulers. American revolutionaries had exactly this so-called right-of-revolution in mind as they expressed their growing dissatisfaction with British rule after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. Therefore, when you read the Declaration of Independence, keep in mind that it is not only a ringing statement of natural rights philosophy—“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal…”—but is also a careful dissolution of the social contract between Americans and the British Crown. The American revolutionaries felt that being taxed without representation, having troops violate people’s property without warrants, and being subject to arbitrary and capricious governance over a period of time were grievances sufficient to warrant a revolution. Indeed, in the words of the Declaration, it is the “duty” of the people under those circumstances, “to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.” The goal of the revolution was not to go back to the state of nature, but to reconstitute the social contract in a form more amenable to Americans preserving their natural rights, safety, and collective happiness.

It’s a long road from Epicurus through Kandiaronk and the Enlightenment philosophers to the Declaration of Independence. Ideas are indeed important, for they can help us get unstuck from the arrangements that oppress us. In The Dawn of Everything, Graeber and Wengrow remind us that people throughout human history and pre-history have tried in numerous ways to live freely, to envision societies without oppression, to prevent the wealthy from translating their wealth into political power, and to avoid having “to surrender their basic freedoms and submit to the rule of faceless administrators, stern priests, paternalistic kings, or warrior-politicians.” (9) Few of these attempts at emancipation are as celebrated as is the American Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration of Independence

In Congress, July 4, 1776.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

References

- Quoted in Matthew Stewart, Nature’s God. The Heretical Origins of the American Republic. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2014. Page 151.

- Thomas Jefferson writing to his nephew Peter Carr on August 10, 1787.

- Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration of Independence was so secular it had no references to the Creator, God, or the Supreme Judge of the World. Those were all added in the editing process done by the Continental Congress. A good description of this editing process is in Danielle Allen, Our Declaration. A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality. New York: W. W. Norton, 2014. Pages 72-78.

- Stephen Greenblatt, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2011. Pages 262-263.

- Dan Allosso, U.S. History and Primary Source Anthology, Volume 1. Chapter 48 on Kandiaronk.

- David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2021. See especially pages 5-95 and 473-525.

- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651). Chapter 13.

- Quoted in Thomas G. West, “The Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights,” in Scott Douglas Gerber, editor, The Declaration of Independence. Origins and Impact. Washington, DC: CQ Press. 2002. Page 72.

- John Locke, Second Treatise of Government, (1690). Chapter 2, No. 6.

- Graeber and Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything. Page 515.

Media Attributions

- Epicurus © Hans Zwitzer is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license