Why Six Core Concepts? So You Can Write ANYTHING

An Introduction to Writing, Rhetoric, Action, Deliberation, Engagement & Contingency

Nikki Mantyla

Ten years into our marriage, my husband and I discovered we had a problem. Specifically, a mouse problem. Actually, the entire neighborhood had a mouse problem. We had moved into a new master-planned development, and the field mice who used to live in the fields that were no longer fields were moving in with us. I couldn’t blame them. The houses were charming.

Mice are cute in an objective way that has to do with being furry. But. There is nothing quite so squeal inducing as seeing a tiny creature scurry across your kitchen and disappear under your fridge. There is nothing quite so gag inducing as finding rodent excrement on the floor of your pantry. There is nothing quite so anxiety inducing as hearing little chewing noises as you try to sleep while they eat through your brand-new home. The mice had to go.

That was my exigency—the situation pushing me to respond. I knew what goal I needed to accomplish (evicting the mice). I knew I needed to maximize the effect (so the mice would stay out). I knew I needed to motivate my husband to agree to whatever solution I wanted to try. I knew I needed to think through lots of options and select the best ones. I knew it would take plenty of effort. And I knew I needed to adapt my strategies to fit the situation.

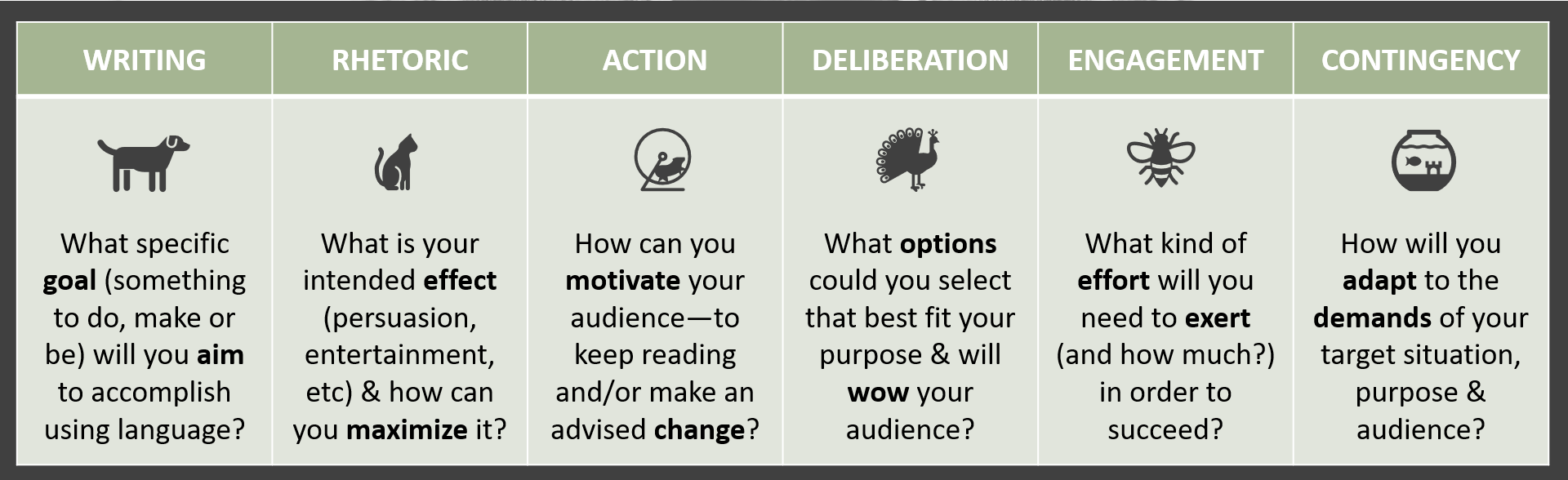

Those bold words highlight the way I see the six core concepts that make up the main sections in this Open English textbook: Writing, Rhetoric, Action, Deliberation, Engagement, and Contingency. While the Welcome at the front of our text provides the theoretical framework for these concepts (mainly of interest to educators), my goal here is to introduce them to students like you in a way that makes them understandable and valuable. In other words, I want to make each concept a strategy you can put to use.

Real-life exigencies like my mouse situation require problem solving, and problem solving requires you to implement strategic concepts so you can discover the best solutions. When your solution involves writing or speaking, the concepts might sound like this:

What’s cool about these six concepts is that, instead of walking you through one narrow approach at a time, like how to write a report or a memoir, they teach you how to write anything.

In fact, I’ve used them to compose this article:

- WRITING ― I’ve tried to aim for the goal of introducing these concepts memorably via stories & analogies.

- RHETORIC ― I’ve tried to maximize my intended effect of convincing you these strategies are valuable.

- ACTION ― I’ve tried to motivate you to change the way you write and try these concepts for yourself.

- DELIBERATION ― I’ve tried to wow you with cool options like photos, charts, icons, bold words, text boxes, etc.

- ENGAGEMENT ― I’ve tried to exert lots of effort into inventing, researching, drafting, & revising until every sentence works.

- CONTINGENCY ― I’ve tried to adapt to the demands of an online textbook with essay format, hyperlinks, headings, etc.

So let’s walk through how I solved the mouse problem, how it relates to writing, and how animal associations might help you remember strategies that will make you a versatile writer.

WRITING — AIM FOR A SPECIFIC GOAL

Writing is a resource people use to do things, be things, and make things in the world. When approaching whatever exigency you face, a good starting point is to decide what you want to do, be, or make—in other words, what goal you’re specifically aiming to accomplish.

Mouse Situation

Broadly, what I wanted to do was get rid of the mice. But I needed to be more specific than that. I began by asking lots of questions in order to understand exactly what I was up against. Since this was a neighborhood-wide problem, I talked with my neighbors to find out the extent of it. They told me about traps they had tried that worked or didn’t work, but they said ultimately more mice kept coming, no matter how they killed them off. I realized that my goal wasn’t to kill the critters; my goal was to drive them away for good.

Writing Application

With writing, sometimes the goal will already be spelled out for you, like an assignment from a teacher or a boss. In those cases, your job is to ask questions and make sure you are clear about the expectations. Other times, you might have personal reasons for writing. In those cases, self-reflection can help you clarify your own goal and decide exactly what you’re aiming to accomplish.

Animal Association

One way to remember this is to think of writing like dog training. Your broad goal is to have a trained dog, sure—but you’d need to specify what that means for you and your dog. Do you want your dog to perform fun party tricks? Fetch ducks you’ve shot while hunting? Walk calmly on a leash rather than dragging you down the street? Become a diabetic-alert service animal? Quit chewing up the furniture? Defining the parameters of your goal is crucial before you can aim to accomplish it!

RHETORIC — MAXIMIZE YOUR INTENDED EFFECT

Rhetoric is a method of studying the work that language and writing do. Analyzing the effects of language teaches you how to impact your audience in intentional ways. In other words, awareness of rhetoric allows you to create and maximize whatever effect you are going for.

Mouse Situation

After pinpointing my goal, I knew exactly what kind of effect I wanted to have on those mice: a terrifying one. I wanted them to quiver in their bones and flee with zero inclination to return. As I analyzed how to do that, I realized we needed a predator. My husband and I had never had a pet, but it was time to adopt a cat―and not just any old scaredy cat hiding under the beds. To maximize the terrifying effect, we’d need a confident mouser with sharp claws and a dominant personality.

Writing Application

Similarly, you have to decide with any writing situation what effect will best meet your goals and how to maximize it. If you want to entertain, you need to analyze how humor works in order to figure out what will best tickle your audience’s funny bones. If you want to persuade, you need to analyze how to sway your audience by appealing to their values etc. If you want to blow their minds, you need to analyze methods of shocking your audience with unexpected twists. The more you pay attention to rhetoric―the effects produced by language―the more you’ll be able to utilize those effects on purpose and maximize them via the strongest techniques. As you do, you’ll also become a more confident writer!

Animal Association

Cats are masters of rhetoric: they meow to pester you into feeding them, purr to flatter you into massaging them, hiss and swipe to frighten you into backing off―choosing the most effective approach for each goal. So be like a cat and be purrposeful about your rhetoric to maximize your intended effect.

ACTION — MOTIVATE TOWARD DESIRED CHANGE

Writing is a form of action. Through writing people respond to problems and create change. This happens most overtly via proposals, open letters, editorials, etc, but a writer takes action any time they compose words hoping to motivate readers toward a desired change.

Mouse Situation

The biggest hiccup in my glorious plan to adopt a ferocious mouser was … my husband. He didn’t want a pet of any kind. To him, traps were better because you didn’t have to commit to housing/feeding them for years! To persuade him otherwise, I had to consider his values. (Notice how rhetoric and action go hand in hand—as do all six concepts.) I knew he loved the NY Yankees. At the time of the mouse debacle, one of his all-time favorite players, Mariano Rivera—whom fans lovingly called Mo—had just torn his ACL while shagging fly balls during batting practice. Everyone thought his career was over, and my husband was understandably depressed.

“What if we name the cat Mo?” I asked. Somehow that did the trick. He agreed to getting a cat.

Writing Application

Action is one of the big reasons writers write: to respond to problems and create some kind of change in the world, even if just within the microcosmic world of their own private life. Pushing your audience toward action, including the simple action of getting them to keep reading to the end of your piece, isn’t an easy task. You have to consider your audience’s values and how you can connect those values to what you want them to do.

Animal Association

Maybe you can remember the concept of action by picturing a hamster wheel. When you use writing to respond to problems and create change, you’re offering your audience a way to jump on board with what you’re suggesting and get moving—even if just by motivating them to read to the end and let your ideas turn the wheels in their head.

DELIBERATION — WOW WITH IDEAL OPTIONS

Writing is a process of deliberation. It involves identifying and enacting choices, strategies, and moves. It means writers have to deliberate about a whole slew of options for their text by deciding which ones will best fit their purpose and wow their audience.

Mouse Situation

When getting a cat, there were lots of choices to consider. I needed a mouser, and I also wanted a family pet for our three young boys, and I thought it would be nice to have another girl in the house, and I imagined a pretty calico cat or orange tabby. But my goal was more important than my preferences. I did some research and found out big male tom cats made the best terrifying predators + chill family members. A friend advised me to pick up each big kitty, flip him onto his back like cradling an infant, and choose the cat that didn’t mind. As long as he still had his claws, such a laid-back cat would also keep the mice at bay.

As luck would have it, a “super adoption” was happening that weekend in a Petco parking lot with 600 dogs and 400 cats. As we walked between hundreds of distraught, meowing kitties, we instantly recognized Mo―a huge fifteen-pound Russian blue / gray tabby mix―because he flipped onto his back inside the cage as if flirting with us. He dazzled us from the moment we laid eyes on him.

Writing Application

In writing, it can be tempting to default to your own preferences, whether a favorite font or a certain layout style, and lose sight of your goal. If we’d chosen a cat based on gender balance and looks instead of personality and size, we wouldn’t have gotten what we needed. As you deliberate about your writing choices, big and small—including ideas, organization, voice, word choice, sentence flow, conventions, etc [see “Movies Explain the World (of Writing)”]—keep your goal in mind. Make the choices that fit what you’re trying to accomplish. Decide on options that will truly dazzle your audience.

Animal Association

Think of how mesmerizing a peacock becomes with his tail feathers fanned out. When you fan out an array of perfectly chosen options in a piece of writing, that’s how you’ll truly wow your audience.

ENGAGEMENT — EXERT THE NECESSARY EFFORT

Meaningful writing is achieved through sustained engagement in literate practices (e.g. thinking, researching, reading, interpreting, conversing) and through revision. In other words, meaningful writing (vs quick notes) is a sustained (long-haul) process that requires you to exert lots of effort.

Mouse Situation

One other hiccup I haven’t mentioned yet: I was allergic to cats. When I visited cat-person friends, free-floating fur would find my face, making my eyes and nose itchy and red. But I was determined to have a mouser, so I poured a ton of effort into research and learned that fur allergies have to do with pet dandruff, which has to do with skin health, which has to do with diet. I then put effort into diet research and discovered that the easiest foods—e.g. dried kibble—are the worst for a cat’s skin, while the healthiest foods—e.g. raw ground poultry mixed with liver, plain yogurt, and shredded veggies—require the most effort.

As of this writing, we’ve had our cat for nine years. That’s nine years of mixing homemade cat food weekly, dishing it into separate little containers, freezing them, and moving them one by one to the fridge in time to thaw for the next morning or night feeding. But I believe in the adage “anything worth doing is worth doing well,” and I haven’t had itchy eyes or nose the whole time Mo’s been with us.

Writing Application

When you read a piece of writing that feels “effortless,” it can be easy to think that writers sit down and type word after word with the same level of ease you are reading them. In fact, the opposite is usually true: the more effortless something seems, the more effort it took to get that result! That’s the ironic illusion. This article required lots of planning, lots of drafting, lots of revising and rethinking and rearranging, rereading (and often rewriting) every sentence dozens and dozens of times. I had to work hard to make it work. I had to really engage with my text for sustained periods of time, trying to transform it from raw ingredients to final product.

Animal Association

Think about how it takes more than 500 bees scouring two million flowers to produce a pound of honey, and how each bee flies more than 25,000 miles to do it. Whatever effort a piece of writing requires, exert it. Make the sacrifice. Dive into research. Brainstorm lots of ideas. Draft and revise as many times as you need to. Be like a busy bee, putting in the hours it takes until you can taste the sweet payoff of a job well done.

CONTINGENCY — ADAPT TO THE GIVEN DEMANDS

The meanings and effects of writing are contingent on situation, on readers, and on a text’s purposes/uses. In other words, the way your writing is perceived depends on where it’s presented, who reads it, how it’s used, etc. Therefore, your best bet is to anticipate and adapt to those demands.

Mouse Situation

I’d never had a cat before. As we filled out the paperwork, the adoption people advised us to keep our cat indoors no matter what so he wouldn’t pick up diseases or get hit by a car. We agreed, but our cat had other ideas. He was eighteen months old and acted like a rebellious teenager protesting his imprisonment: trying to dart between our legs any time the door opened, clawing at the carpet as if he could dig under it to escape, pooping on the rug despite being fully litter-box trained.

After almost a year of pet-owner hell—during which my husband dramatically decreed, “It’s me or the cat!”—I became so sick of Mo’s temper tantrums that I opened the door wide saying, “If you want to go out so badly, go!” Five hours later he hadn’t come back. I was sick to my stomach. The kids were crying. Even my husband who claimed to hate the cat was worried.

Then we heard a meow from the other side of the door. Mo walked back inside a model citizen, never terrorizing the carpets again. We adapted to his needs by installing a cat door for him to come and go as he pleased. We threw away the litter box since he preferred to bury his business outside. Everyone was happy.

Writing Application

This last concept, contingency, deals with things beyond your control. You chose your goal, your effect, your motivation, your options, your level of effort; next you have to work around the aspects you didn’t choose—the ones inherent to your situation. Each piece of writing will have its own demands. Maybe it needs to be in slideshow format for a presentation. Maybe it needs to change from a short story to a film script. Maybe it needs to fall within a 50,000–70,000 word-count range to be considered for publication. Identify the needs of your audience, purpose, situation, etc and adapt your writing accordingly. Just as I couldn’t force an outdoor cat to be an indoor cat, there will be aspects of your situation that require you to make adjustments.

Animal Association

Think of it this way: a fish has to live in water. There isn’t any way around that! So if you want a fish as a pet, you would have to adjust to that situation by acquiring a fish bowl or fish tank, filling it, prepping it, and meeting all the fish’s other environmental and dietary needs. Likewise, be aware of the demands of your writing circumstances so you can adapt and prepare as needed.

WRITE ANYTHING

A week after we brought Mo home, I watched a mouse run out of our house, across the yard, and far away to find a new place to live. Since then, the only mouse problem we’ve had is cleaning up the occasional “present” that Mo might leave on the welcome mat after his nightly hunts. Though I never wanted to deal with dead bodies, at least they’ve been fewer than if I’d set traps. The living mice tend to avoid us—exactly as I’d hoped.

Also, we got a pretty great family pet.

Goal(s) achieved.

As for this essay, whether or not I succeeded depends on what you got out of these paragraphs. I hope they’ve empowered you to problem solve each writing situation you encounter—each exigency—step by step:

- WRITING ― aim for a specific goal

- RHETORIC ― maximize your intended effect

- ACTION ― motivate toward desired change

- DELIBERATION ― wow with ideal options

- ENGAGEMENT ― exert the necessary effort

- CONTINGENCY ― adapt to the given demands

Do all of that, and I bet you could write anything.