Why We Might Tell You “It Depends”: Insights on the Uncertainties of Writing

Justin Jory and Jessie Szalay

SOMEWHERE, A STUDENT DECLINES TO ENROLL IN A CLASS

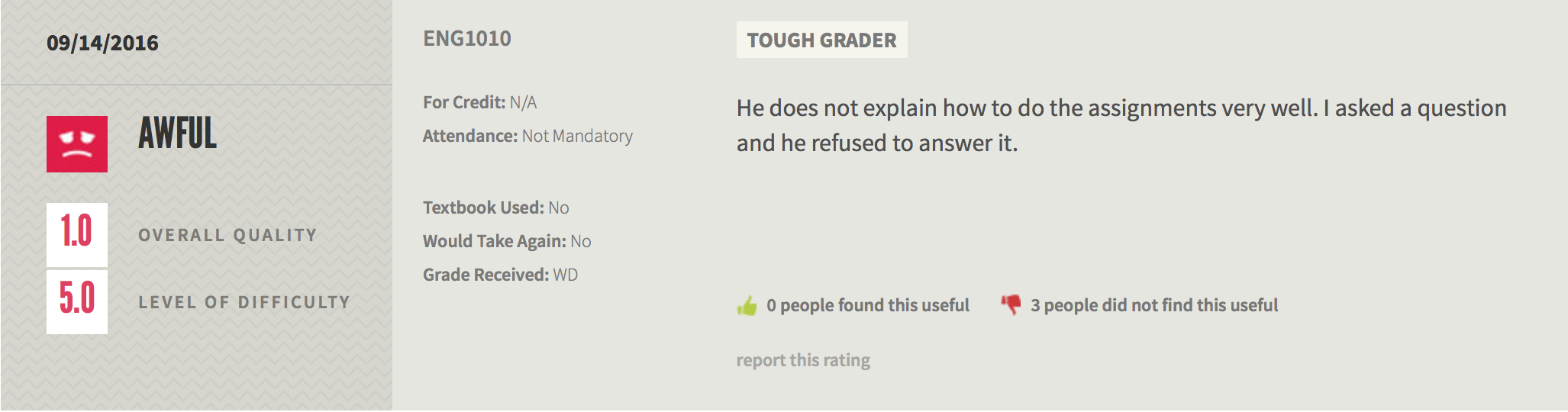

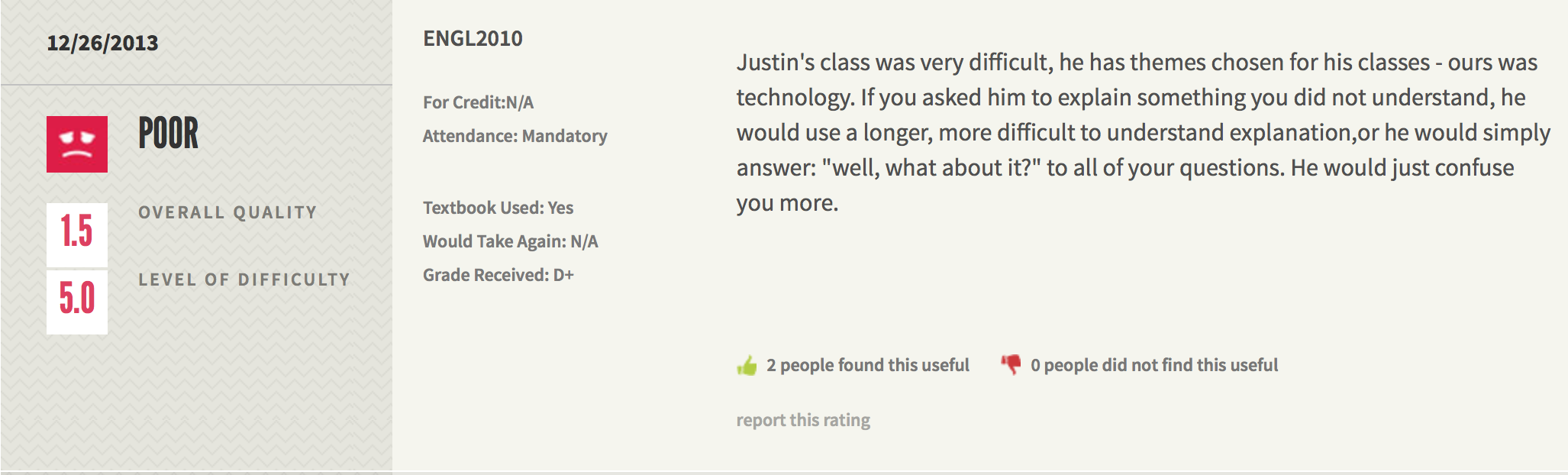

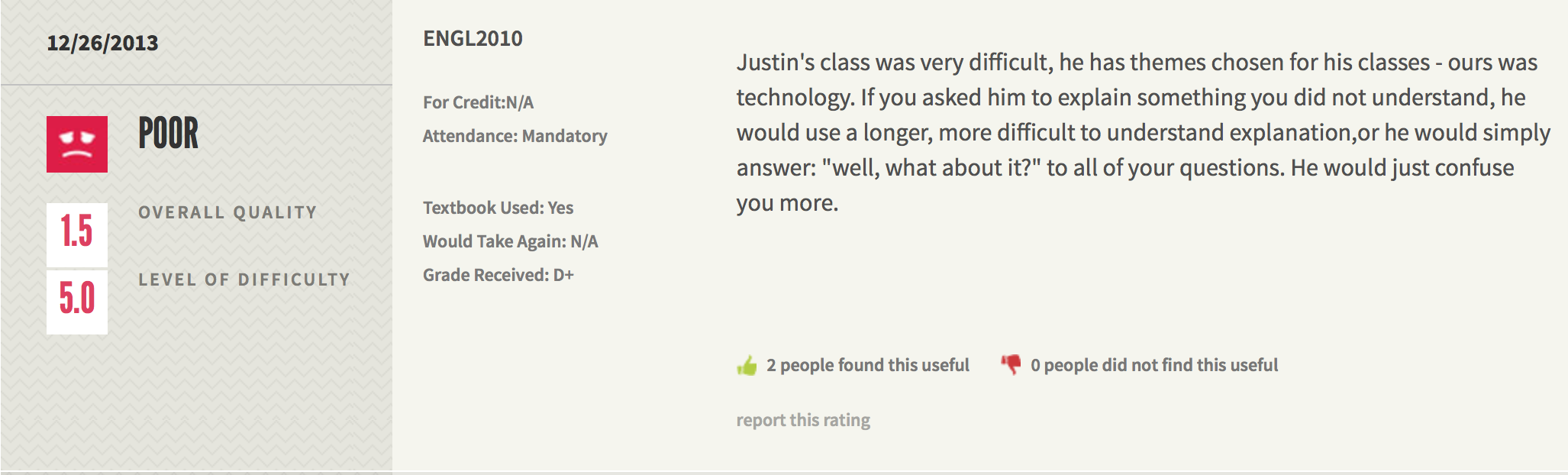

Rate My Professors (RMP) may seem an unlikely place to go for a critical discussion of contingency in writing, but we think these comments—which are valuable texts in helping students select teachers—are interesting because of what they choose to make known and leave unknown, what they say and how they say it, and what they leave unstated or simply cannot capture. Consider two recent comments on Justin’s RMP page.

One way to read these comments is to notice that they both address Justin’s refusal to answer students’ questions, and they seem to suggest that he simply doesn’t care to help students or, maybe even, that he aims to confuse students with long answers to their questions when possible. If you read the comments in this way, then you might also read Justin as a terrible person. At the very least, you may imagine him as an unsupportive teacher at the moment you are selecting classes and decide against taking his course.

Another way of reading the comments is to situate them in the college-level writing classroom and to consider them in that context. We want students to understand and internalize the idea that writing is an act of deliberation. And what we deliberate about often comes down to the contingencies within a writing situation. So, when a student asks Justin for step-by-step instructions on how to write a persuasive argument and he tells them “it depends,” he’s asking them to think about what their writing is contingent upon. Who is the audience? How will they receive the piece of writing? What do they know about the subject already? What are their biases? What are their values? What is the author’s goal? What research do they have to support their argument? What personal experience do they have? These questions, and many more, are contingencies upon which we make our writing choices.

CONTINGENCY + WRITING

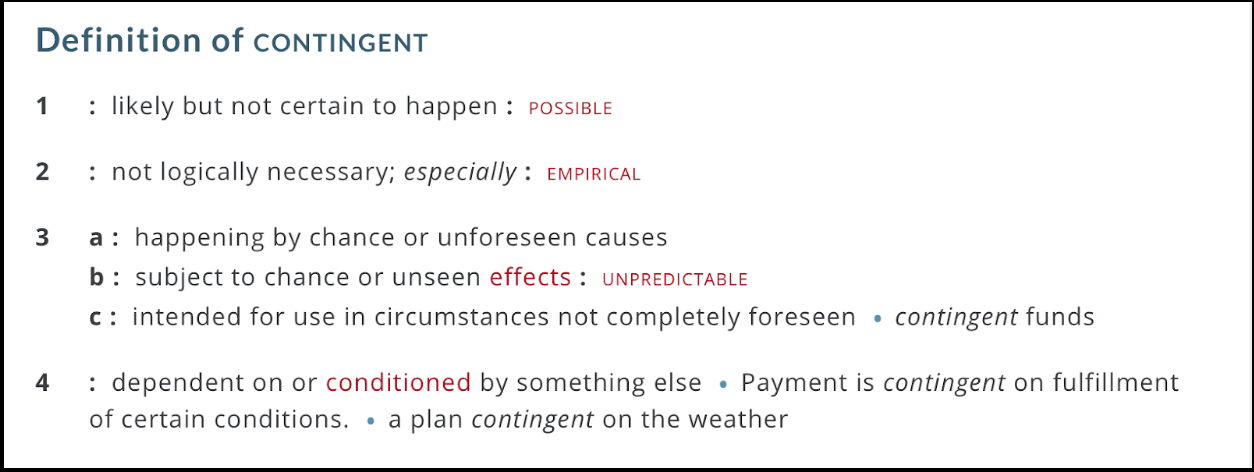

You’ve probably heard the term contingency plan. That’s a plan for when the unexpected happens, usually a bad thing. The situations that contingency plans address are as varied as the information the plans present. The situation cannot be avoided with any certainty. Contingency plans are about predicting the unknown so that, should the moment arrive, the plan might offer the best information at the right time to people who need it.

Contingency in writing isn’t necessarily about planning for a worse-case scenario, but it is based around considering and responding to unknowns and providing readers with writing and information you think will be the most useful to them. In this way, contingency in writing is the most like the last example of the fourth definition: a plan is contingent on the weather, which no one can entirely predict but about which we can make good guesses; the success of a piece of writing is contingent on the audience and the way the text is used, which no one can entirely know but about which we can make good guesses.

Learning how to identify, interpret, and respond to the known and unknown factors in any writing situation is one of the most important aspects of developing as a writer. This is because writing must account for and respond to these factors, and doing so effectively is what makes writing meaningful. The devil, as they say, is in the details, and attention to the details of writing is what threshold concepts like the following aim to highlight:

To say that writing is contingent on something is to suggest that writing is only meaningful in context (among people acting in particular situations and locations). To consider writing’s contingencies is to think about those things that make writing more or less meaningful to the people in those contexts. Writing is to a large extent the process of moving from uncertainty to the best educated guess, from identifying what is possible in writing to making writing that responds to your situation and context meaningfully and effectively.

To put it another way, when we begin to write, we are in a place of not knowing. Even if we know what we’re going to write about, we often don’t know how we’re going to say it or to whom. But as we start deliberating, as we start thinking more carefully about the details of what we’re doing and why, we realize that some of those uncertainties may become more certain, cuing us in to what we should or shouldn’t do, while others remain unknown and unknowable.

All writing is based in uncertainty to some degree, and the most experienced writers learn to systematically identify, interpret, and respond to the most salient factors that give writing meaning in any given situation.

RESPONDING TO WRITING’S CONTINGENCIES

Making educated guesses about the things that influence your writing most in any given situation takes practice. Writers have to develop a keen attention to the details that make writing meaningful and useful within and across contexts.

For example, paragraph length is a relatively small detail that Jessie has learned is quite important depending on the context. When she writes, her paragraph lengths are contingent upon the situation. If she’s writing a newspaper article, they will be shorter because that is a standard convention of most newspaper writing. If she’s writing a literary analysis, they will be longer because detailed academic writing allows them to be.

Some unknowns are easy to deal with because you can easily find information to guide you. When Jessie started writing for newspapers, she had only to read some other articles to learn that paragraphs tended to be short. She figured keeping her paragraphs between 1 and 3 sentences long was a safe bet.

Here’s an example of a short paragraph from an article about restaurant business. (It even has a fragment, another convention of news writing. Whether a fragment is considered a grammatical device or an error depends—is contingent upon—the type of writing being done.)

Today, Pincho Factory is popular, profitable, and set to open its 10th and 11th stores. But its initial growing pains aren’t uncommon. Whether limited or full service, many restaurants have struggled when going from one to two stores.

Of course, there are some things you cannot know for sure as a writer, but you can still learn to make educated guesses about them. This requires asking the right questions. The specifics of the questions will change depending on the particulars of your situation, but we can identify some places to start.

Survey the Rhetorical Situation to Learn What Is Known and Unknown

Depending on the situations you find yourself writing in, there are different strategies for learning about the knowns and unknowns. These include everything from gathering information through more field-based methods like interviewing your audience or observing them in a relevant context to doing some reflection about who they are, where they’re coming from, and what it all means to your job as a writer engaging with the audience in any given situation. For this kind of work at SLCC, we often refer students to the rhetorical situation.

Broadly, surveying the rhetorical situations involves asking three questions:

- Who is the author?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Who is the audience?

These questions can yield a lot of information, but we can take them all deeper to learn more and get better answers to the fundamental question: What kind of choices can you make that will enable your writing to be successful?

Let’s look at the first two questions to further explore your own position as a writer. About these, we can ask deeper questions like

- Who are you? What is your background, your perspective, your privileges and disadvantages?

- What is your relationship to this topic? Is it something you have studied academically for years or are just learning about? Is it something you have personal experience with, or do you know someone who does? Why do you feel about it the way that you do?

- What are your goals, specifically? Do you want to inspire action? Change minds? Ask questions? Share a story? Entertain?

- How do you like to write? What is your writing voice (if you know)? How do you want the experience of reading your writing to be—peaceful, beautiful, dry, cheerful, funny?

Now let’s consider the audience. These questions assume you’ve already thought carefully about your audience and narrowed it down to a precise level (“My audience is everyone,” isn’t very useful).

- What is your audience’s relationship to this topic? How much do they know about it? Why do or don’t they know about it? Do they have values associated with it? Where do those values come from?

- How and when will they encounter this text?

- What type of writing are they most likely to engage with? What type of language or English do they use and feel comfortable with?

- How are they likely to respond to this text?

Drawing on our prior knowledge, engaging in research about genres, and surveying the rhetorical situation in a meaningful way might provide us with enough information to address the contingencies in our writing sufficiently and allow us to make good, educated writing choices. Let’s say I’m a paralegal writing a brief. The question of “what form should I use?” will quickly be answered because there is an institutionally agreed-upon form for legal briefs. I may have some degree of certainty about how my manager will receive the legal brief, which likely comes from contextual knowledge of sharing many legal briefs with her over many years. Similarly, if I am a coffee shop manager writing an instruction sheet for workers on how to make a cappuccino, the question “to whom I am writing and what jargon should I use?” can be answered with some ease.

But the most effective genre in which to reach these workers? That’s where careful consideration of my audience and what they value is helpful. I might decide that a printed, bulleted Word document is not the best way to reach them. Instead, I might decide to make a colorful, step-by-step infographic and post it near the cappuccino machine. And if I really want to tailor the infographic to my workers and our workplace, I may include inside references in an effort to take instructive information and make it fun for this particular community of baristas. It’s up to me.

Surveying the rhetorical situation is an ongoing activity, an iterative process, where writers continually notice and make sense of new knowledge to determine, more generally, what they know and don’t and how it will influence their writing.

Undertake an Act of Imagination and Think About the Broader Contexts

If I’m a paralegal or a coffee shop manager writing a brief or cappuccino instructions, I’m dealing primarily with contingencies I can address with knowledge and educated guesses. But what about writing for more abstract audiences and purposes? After all, writing is more than a simple one-on-one exchange of meaning. At its most powerful, writing can facilitate conversations and relationships between individuals by making writing choices that are meaningful to the people involved. Most college instructors want to see their students do this type of writing, rather than simply prove they know about a topic.

Often, college students have a hard time answering their questions about what writing choices to make (what form, tone, tense, style to use; how to structure their ideas; etc.) because the contingencies—the audience and their reaction, the way a text will be encountered, the values being conveyed and responded to—feel impossible to nail down and identify. They may be, or at least appear to be, further away from students. They are surrounded in mystique and it seems that only authors with more authority or power, like politicians, scientists, journalists, and other experts, have the ability to make educated guesses about these contingencies.

But that’s not true; most everyone, including college students, has the right to speak to most every audience IF they engage them in an appropriate, educated way. It means using a mix of imagination and thorough research to think about what their experience of reading the text will be like. You can look to the questions in the previous sections for guidance; in these situations it is especially important to understand what your audiences likely know about the topic already and what their values might be. But you should also think more broadly and use your imagination to try to make good guesses about lives, and, consequently, reading experiences, that are different from yours.

For example, Jessie loves dogs, grew up with them, and feels comfortable around them. Let’s say she wants to invite her friends over to meet her new 100-pound mastiff. She knows that some of her friends are a little nervous around big dogs. When deliberating over the e-vite wording, she can ask questions like, “What does my audience value?” One answer is that they value friendship and parties, so Jessie will write something about how excited she is to see everyone. She’ll pick an e-vite that conveys fun. She’ll mention all the good food she’ll have.

Another answer might be that her audience values small dogs but not big ones, but more thorough imagining shows that’s not really correct. We can imagine what it’s like to be in Jessie’s friends’ shoes even if we don’t know the specifics. Why would someone be nervous around big dogs? Perhaps they had a negative experience. Perhaps they’ve never spent time around one. Jessie can imagine what it would be like to see a huge, unfamiliar dog running at you. It might be scary!

By using her imagination, Jessie can understand that her friends value safety and security. Perhaps they value personal space and are worried that a big dog could knock them over. So, Jessie will make some educated guesses in her writing to reassure her friends that they can feel safe around her dog. She might include a cuddly picture rather than one that demonstrates the dog’s size. She might reassure them that he’s a big teddy bear and very well behaved. She might mention that he’s been going to obedience school. She might mention that he has a very comfortable bed in the laundry room and he can always be put in there if his presence gets to be too much.

The success of her writing—and her party—is contingent upon her ability to accurately imagine what her audience’s feelings around this topic are.

CONSIDERING CONTINGENCY IN STUDENT WRITING AT S.L.C.C.

What a Little Investigation Can Reveal About Audience and Content

Recently, one of Jessie’s students wanted to write a letter to Governor Herbert about the air quality in Utah. The students’ audience, medium, and message were certain, as demonstrated in the weeks of detailed process work he had completed, but there were still a number of things he had to make educated guesses about. How would the letter be received? He didn’t know, so he did research and made an educated guess (answer: an intern will receive it and decide whether or not to pass it along to the Governor’s staff, who would decide if they should pass it to the Governor himself.) He then folded that knowledge into his creative process and made rhetorical decisions that he thought would get the attention of an intern and increase his chances of getting the letter passed onto the governor.

A good portion of his creative energy was spent considering his writing in context of two readers: Governor Herbert and his intern. Since Gov. Herbert was his primary audience, he needed to make sure the information he selected for his letter was valuable to him. What did Governor Herbert know about air quality in Utah, and how much of the letter should be devoted to describing the problem? While the student had to educate himself on the reasons for our pollution problems, he made the educated guess that the governor had likely heard all of this information before and knew the statistics about health risks, tourism risks, etc. Therefore, he decided to minimize his project’s references to research-based texts that Governor Herbert would likely be familiar with. Instead, he described his family’s personal experiences with worsening asthma in Utah. He hoped this would impact Governor Herbert. He also considered that the intern needed to find the information—in its form and content—moving enough to take the next step and pass the text to Governor Herbert.

At every step of the way, Jessie’s student was negotiating the details of his letter by surveying the rhetorical situation he found himself writing in and using the knowledge he gained about his audience(s) to shape the content of his letter. Jessie’s student, in other words, was working through writing’s contingencies head-on.

What This All Means For You

We know our students are busy, perhaps overwhelmed, and likely concerned about their grades. It makes sense that they want clear, precise instructions from their teachers. But keep in mind that, if you ask a writing teacher a question and get a long, complicated answer, that answer might actually be providing you with the information you need. It might not actually be a complicated answer but a series of specific questions that you need to engage in the project.

That writing is based in uncertainty means that there are often no clear answers or definitive responses to questions like, “How should I…” or “Can you tell me exactly what I need to do in this assignment?” or “Should I do this or that?” And, even when there are better answers or responses, we want student writers to demonstrate the thinking that has led them to realize those answers. In short, the deliberative process of writing—what instructors at SLCC see as the process of problem-solving writing’s uncertainties, or its contingencies—requires that students know when to pose the right questions to help them think through writing.

So, think about this:

Perhaps Justin did refuse to answer the student’s question. Perhaps the assignment sheet wasn’t as detailed as what the student was used to. And maybe Justin did delay providing definitive answers and suggestions so the student would engage in the thinking work necessary to answer it themselves. Maybe Justin told both of them, “It depends”—because it does.