Critically Thinking About Credibility

Tiffany Rousculp

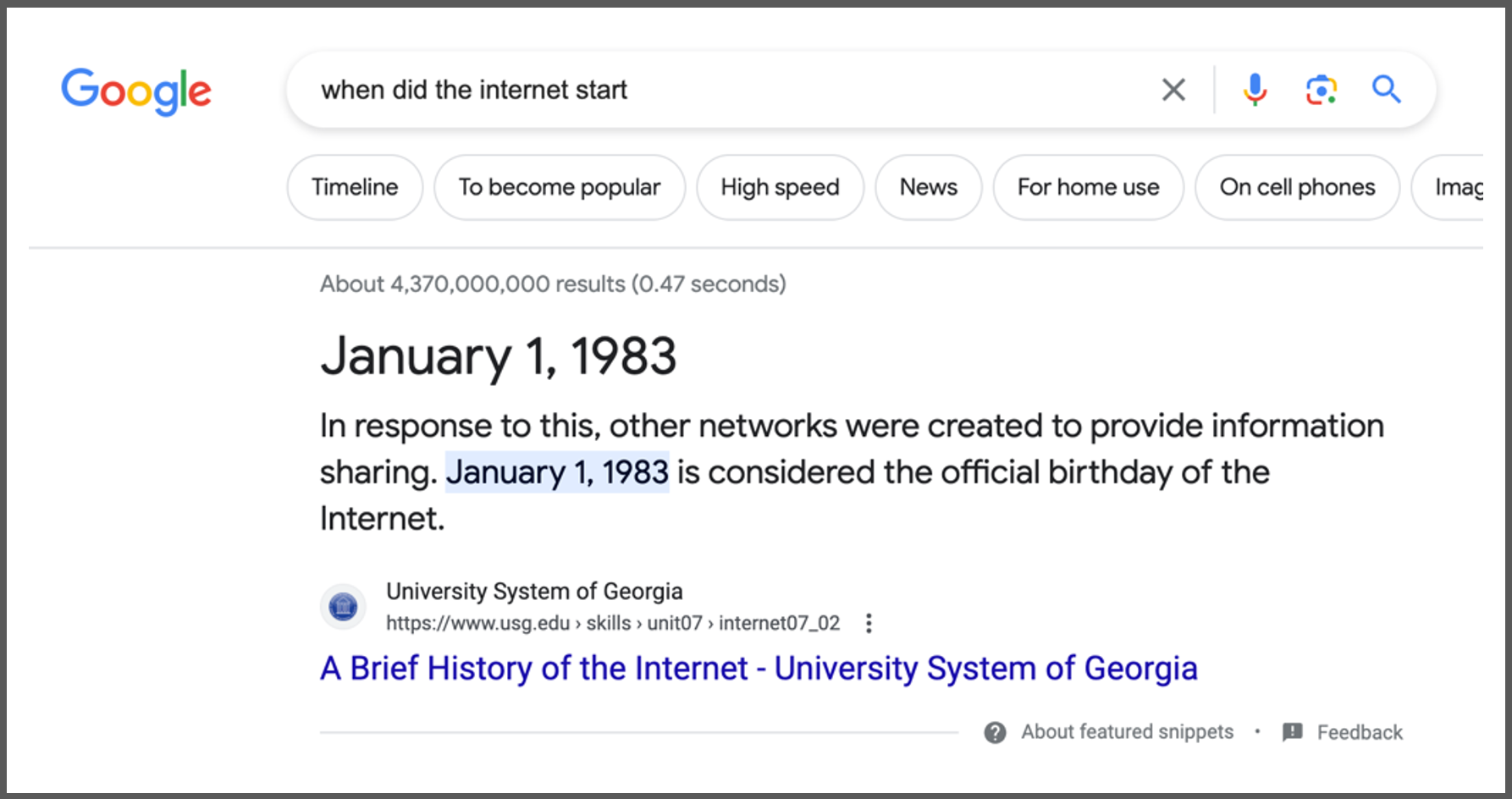

Did you know that the internet started on January 1, 1983?

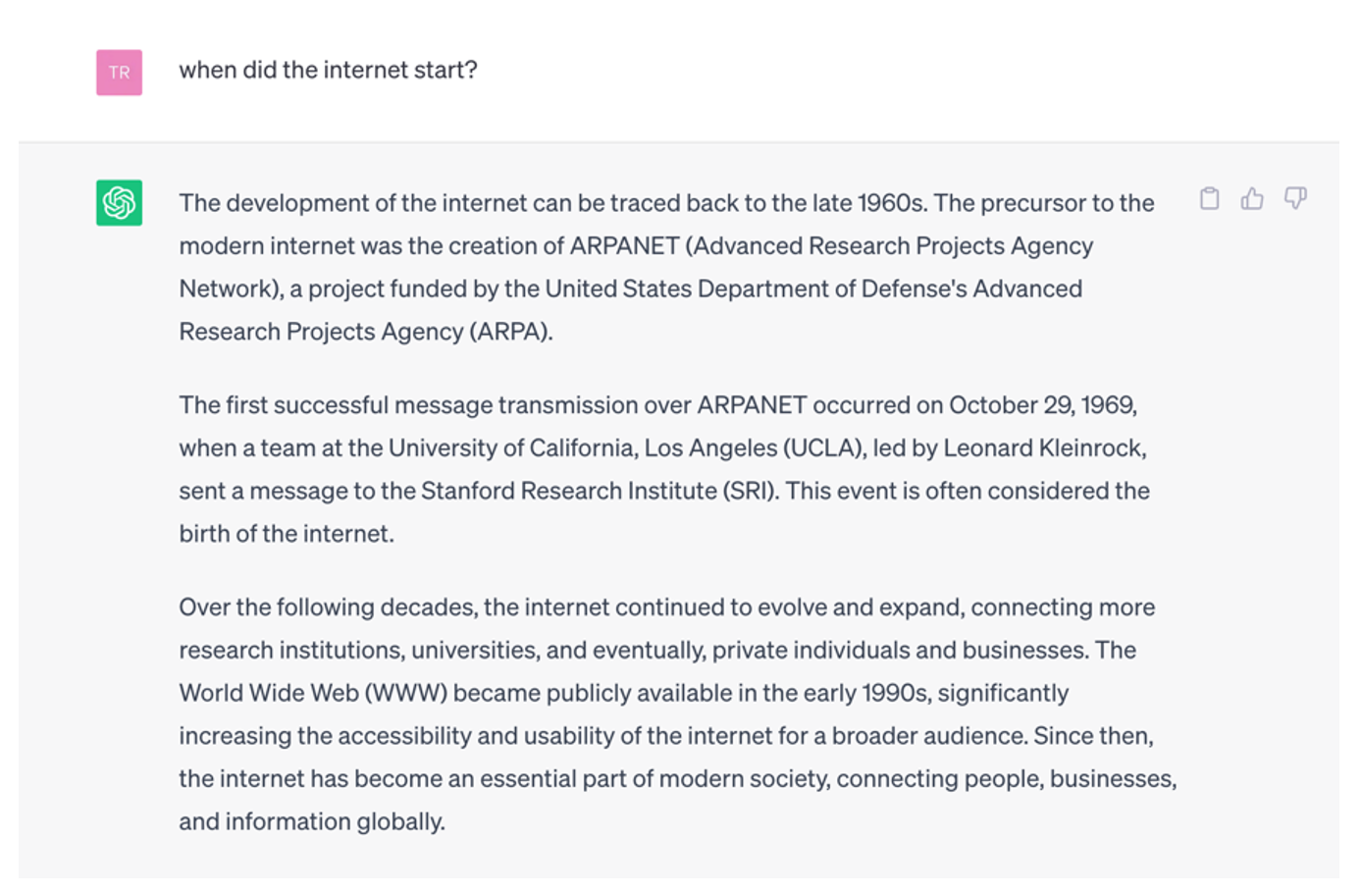

This surprisingly specific fact only took 0.47 seconds to find in a search that asked, “When did the internet start?”

This surprisingly specific fact only took 0.47 seconds to find in a search that asked, “When did the internet start?”

Actually, though, Google is wrong. The internet started on October 29, 1969. At least that’s what ChatGPT, the chatbot using generative artificial intelligence (AI), replied when asked the same question:

This is a fairly straightforward request for information, but the responses—both of which are generated by scouring the internet’s billions of sites and documents to produce a result—are off by 14 years and make very different assumptions about what “start” means. Going to SimpleEnglish Wikipedia confirms the ChatGPT response of 1969, but then complicates things with “The World Wide Web was created at CERN in Switzerland in 1990 by a British (UK) Scientist named Tim Berners-Lee.”

It’s not actually important (or, really, even possible) to know the precise date that the internet started—unless you are a contestant on the game show Jeopardy and the final round’s prompt is “This important connection was made on October 29, 1969”—but it is important to understand how to critically determine if information, opinions, facts, evidence, and stories are credible. Learning this skill and which elements of credibility you most value is some of the most important critical thinking growth you can develop while you are in college.

To make the point above, I could have searched for any complex bit of information, but I intentionally chose the start of the internet. Why? Because the birth of the internet is directly related to the steep decline in trust and increased difficulty in determining credibility in sources. Our levels of trust are very low; we live in biased bubbles of information and opinion that typically confirm what we already think and believe. We tend to automatically distrust anything outside of our comfort zones of family, community, and our social media groups.

This is not the internet’s fault though; in fact, the internet has been a democratizing force: it has allowed individuals and communities to share their knowledge, experiences, and realities beyond their immediate communities. Isolated individuals and groups have been able to connect with each other in ways impossible before. Creativity and diversity have exploded into new ways to express ourselves and to learn from each other. No, the internet is not to blame.

The internet + making-money-off-of-the-internet is the equation that has led to eroding levels of trust and increasing polarization among people and communities. In order to make money, companies must keep our constant attention; they need us to stay logged on or tuned in, clicking away, waiting for the next post, story, or news item.

Keeping our attention didn’t start with the internet though; that was years prior with the first 24-Hour Cable News Network (CNN) in 1980—and grew dramatically with FOX News in the 1990s.

One way to keep our attention is to make us feel like we “belong to” a group and that others who don’t belong, who don’t have the same information we have, are mis- or dis-informed, or just plain wrong. We are Republicans or Democrats. We are members of a religion or are atheists. We are pro-choice or pro-life. Whatever we are, we’re going to trust those in our group, and certainly are not going to trust what someone outside of it has to say.

This cultural norm of high polarization is a significant challenge that college students face today. Many of you have grown up within the highly distrustful media and internet landscape so it’s just normal. When your instructors tell you that you need to have credible sources, sometimes what they think is credible is not what you think is credible. What do you do then? Let’s take some time exploring credibility and how you can critically determine credibility for yourself and advocate for its credibility in your classes in college.

In your previous classes, you may have learned that credible sources are only found in the library or in books. But credibility is more complicated than that.

Credibility is a characteristic or quality of a person or a source (e.g., news, information, opinion, story, experience) that can be trusted or believed in. Credibility is often associated with expertise or experience. For example, an emergency room doctor is more credible in determining whether my toe is broken than a lawyer would be. The ER doc has more training and has seen more broken toes than lawyers have.

Expertise is not the only factor involved in credibility, however. Consistency is also a crucial element for building trust or belief. Let’s say the ER doc misdiagnoses 67% of broken toes and sends patients back out into the world in severe pain. While the ER doc might have expertise, they clearly are not credible to diagnose broken toes. Maybe they’re great at ear infections but keep them away from any stubbed toes.

Character is another element of credibility. Character is a little harder to define but think of it as reputation—or how a person, group, or source tries to present themselves or is seen by others. Let’s go back to the ER doc and examine how character might influence credibility. Let’s say the doc misdiagnoses the broken toe, but upon realizing it, calls to apologize and offers to get you back in right away for treatment. You would be more likely to trust that doctor than one who realized they made a mistake but never followed up on it.

The last element of credibility is related to character but is outwardly focused: purpose or intent. A person’s or source’s purpose or intent is essential to determining its credibility. One more time back to the ER and our doctor: we’re in the examination room; our doctor is peaceful and focused on us and our pain. We are more likely to trust their diagnosis than if the same doctor rushes in, checks the clock, says “Thank goodness, you’re my last patient,” and barely looks at our toe before saying, “It’s fine,” then turns away and leaves. One doc’s purpose was our well-being; the other wanted to end their shift.

Credibility and credible sources can be found in library databases or published journal articles and books that your teachers send you to find. But credible sources can also be found in many, many other places.

- People You Know: Your family members, friends, elders, co-workers, community leaders, and more can be credible sources. In fact, you, yourself, can be a credible source on many matters.

- News and Media Sources: We all know that news and media sources are biased; they have opinions and share information in ways that will keep their viewers/listeners interested. Bias does not mean that it cannot be trusted, however. Bias simply needs to be taken into consideration while you are deciding whether the purpose/intent of a source is what you consider credible.

- Internet Sources: You may hear in college that internet sources are rarely credible. While some sources are not trustworthy at all (if you analyze them according to the qualities above) others certainly are.

- Social Media: People create social media, so if people can be credible sources, it is logical to assume that social media can be a credible source sometimes as well. At the same time, however, bots and algorithms also create social media, so assessing the credibility of its sources is very important.

An emerging source that is becoming huge now is generative AI. Programs like ChatGPT, Microsoft Bing, and Google Bard can provide basic credible information just like Wikipedia can. But, just like Wikipedia, generative AI gets its information from the sources above, and sometimes gets it wrong.

Regardless of your source—whether it’s your grandmother or a TikTok post, a scholarly article or a historic book—there are a few fundamental critical thinking steps to determine whether it is credible for the purpose you wish to use it for.

- Review the four qualities of credibility. Examine your source through the qualities of expertise/experience, consistency, character, and purpose/intent.

- Does this resource have expertise or experience in what it is saying?

- Does this resource have a good record of being correct and accurate?

- What is this resource’s reputation?

- What purpose does this resource have in providing this information, opinion, fact, or story?

- Read or search laterally (i.e., “side-to-side”). Confirm what your source shares by trying to find it somewhere else. Look at two or three different news sites to see if they say the same thing—or at least something similar. Even better, look at sites that are in different “bubbles” (e.g., liberal, conservative). What they agree on is likely the most credible information. If they don’t, keep searching laterally.In the “When did the internet start” exploration above, lateral searching made the information more complex, but also more credible. Eventually, it became clear that one critical part of the start of the internet happened in 1969, another in 1983, and still another in 1990. These three dates showed up in multiple sources. If you find material that you think is useful only in one source, it’s probably not very credible.

Lateral searching is becoming more and more important with the rise of generative AI information. AI content generally seems completely credible, but it is sometimes quite incorrect or inaccurate. If you use generative AI, be sure to always search laterally, as well, for confirmation.

Another strategy for lateral searching is to find out information about the source itself. Maybe you’ve found just the resource that you need, but you’ve never heard of the author or source. Maybe it’s an article in TruthOut or The Economist. You can search for the author or source and see what they say about themselves or what others have to say about them.

This is where Wikipedia works wonders. Look up the resource (a person or an organization) on Wikipedia and you’ll likely find information on all of the four credibility qualities above.

- Pay attention to your confirmation bias. As explained above, we are more likely to distrust sources that differ from or don’t agree with what we already know, believe, or trust. On the other hand, we are more likely to believe sources that agree with—or confirm— what we think or what we want to think. This is called “confirmation bias.” Everyone has confirmation bias, regardless of how open-minded you are. It’s human nature.However, a source’s actual credibility is irrelevant to whether or not you agree with it. Pay attention to your feelings or reactions when you are reviewing or analyzing sources. Does a source give you a little positive jolt of “Yeah, I knew it!”? This can be subtle, but it’s definitely a good feeling. This is confirmation bias, and it can give the source more credibility than it, perhaps, should have. At the same time, you might assume that a source is less credible if your response is “No way, that’s not right.”

Confirmation bias explains why it feels easier to do a critical analysis of a source that you disagree with than one that you agree with.

You won‘t be able to stop your confirmation bias, so simply pay attention to it. Be aware that it exists and that your work might benefit from looking a little more critically at sources that you agree with; give them the same scrutiny as you would to those that you don’t.

There are other methods to determine credibility of sources that you will likely encounter in your college career. Known as “credibility checkers,” these resources can be very useful to give you a structure and set of questions to analyze a specific source. Information literacy specialists in the college library can offer you these resources and many of your instructors are probably familiar with them.

Common credibility checkers include “CRAAP,” “TRAAP,” and “SMARTCheck.”

These credibility checkers can feel like busy-work or jumping-through-hoops unless you are also able to critically think about how to determine credibility. By understanding the qualities of credibility, getting used to reading laterally, and being aware of your confirmation bias, you’ll be able to use these checkers more effectively and to support your work.

Also, and most importantly, by critically thinking about credibility, you will be able to expand the sources available to you in your college classes. You’ll be able to explain to your instructors why your uncle or your community leader is, in fact, a credible source for a project you are working on. You’ll be able to include sources from the virtual communities that you belong to. And, finally, you’ll be able to open your mind to, and trust, sources that you may not have been able to before.