Is That a True Story?

Ron Christiansen

For many years I did not teach narrative writing (fancy name for stories) in my writing classes. To be honest, I was unsure how to do it effectively and a bit nervous that my colleagues would perceive me as unaware of the current trends in writing theories, which focused more on so-called academic writing—see expressivist pedagogy vs. social constructivism and critical pedagogy or ask your instructor about this if you are dying to know more.

We can see the broad (i.e. not caught up with this specific debate with my colleagues) tensions and problems in my title, “Is That a True Story?” This use of “true” seems to assume we have easy access to the truth. And our general use of the term “story” almost always connotes “made-up, creative, for fun.” So it is ironic, indeed, that I now embark on a story about my teaching in order to make a somewhat academic argument for a particular way of seeing and using stories in the writing classroom. Well … on with the story.

PUTTING STORIES BACK INTO MY WRITING CLASSROOM

When creating my English 2010 class without a textbook, I decided it was time to revisit narrative writing, specifically memoirs, to see if I could figure out how to teach this type of personal writing in a more rhetorical way.

The first semester of my return to narrative writing, I ran into an unexpected problem, something I hadn’t thought much about. Often when I gave feedback on early drafts of memoirs, I would ask students to offer more details and more specific scenes. But generally students seemed to ignore my feedback or in one way or another say that they were not able to flesh out the scene. Sometimes I assumed students were simply being a bit lazy; eventually, I realized that students were actually asking a specific question in order to figure out if their writing would be acceptable in this particular rhetorical context: “Does my story have to be true, like completely true?” You can see a student imply this question in this exchange:

TRUE OR NOT TRUE?

People often ask if a story is true. In fact, as a culture, we are a bit obsessed with truth. But what exactly are we asking when we directly or indirectly ask if a story is true?

It appears that we are asking if something literally happened. And that seems easy enough, right? Let’s explore this with an experience I wrote about from my life some time ago. When I was twelve or thirteen, my cousin, Jeff, and I helped my grandmother clear out her attic. It was a huge job as stuff had been crammed up there for decades. In my memory, we found hundreds of old beer bottles that my cousin and I tried to save but my grandmother only allowed us to keep twelve each. I imagined my Mormon grandmother was embarrassed that her husband, who had died many years before when he was only forty-six, had made his own beer because alcohol was frowned upon by most Mormons. Yet when I asked her about it later, she insisted there were only twenty bottles or so, all of which we kept, and that, no, she was not embarrassed because the bottles were not my grandfather’s and he did not make beer.

Who to believe?

There is no way to tell this story without some level of interpretation. The “truth” is getting a bit complicated.

Many years later, after my grandmother had passed, I asked my cousin about this story. He agreed there were many more than twenty beer bottles that our grandma forced us to take to the garbage dump. But as we got to talking, he remembered that our grandmother bought us off, letting us keep twelve of the beer bottles and two old wine bottles plus ten dollars apiece, if we kept what we found between us. I had no memory of this, yet I had already written up the story.

WRITING AS DECISION MAKING

Now, I had a decision to make about truth, but also about the overall rhetorical situation and purpose of my story: Was the story I had written a lie? Was it simply my version? Who did I imagine as my audience? Should I add what my cousin had revealed even though I had no memory of it? Should I offer the competing accounts? There is no right answer to these questions. Awareness of the decision-making process itself is the core of effective writing.

I would argue, however, that one thing is clear: the minute we start to retell a story from our past we are constructing it from our point of view, so there’s no need to get too worried about getting every detail correct. It’s impossible.

Still, stories presented as true clearly impact us differently than “merely” fictional ones. Think of the rise of reality TV. Think of our fascination with true crime TV shows and podcasts (e.g. the Serial podcast or Netflix’s Making a Murderer). We want stories to be true. My guess is what we actually want are stories that speak to us, that speak to the human experience.

EMOTIONAL TRUTH

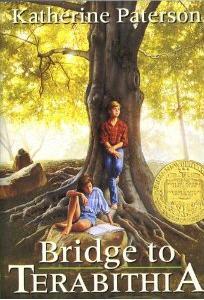

When Katherine Paterson is asked if her fictional novel Bridge to Terabithia is true, she replies, “I hope so. I meant for it to be true. I tried hard to make it so.” But, strictly speaking, it’s not true. That is, there wasn’t a boy named Jesse who built a magical land across a river where, later, while he was away on a day trip, his friend Leslie visited. On that day the river was swollen because of run-off and she fell in and died.

It turns out, however, that when Paterson wrote the novel she and her family had recently dealt with the death of their son’s best friend and the author had a close call with cancer. Even though the facts of the story didn’t play out that way, the story clearly represents the emotional truth of how these families, both the author’s and the fictional, dealt with death.

This idea of emotional truth is also important in nonfiction stories like memoirs. Monisha Pasupathi, a professor of developmental psychology at the University of Utah, suggests, “What really matters isn’t so much whether it’s true in the forensic sense, in the legal sense.” Instead, “What really matters is whether people are making something meaningful and coherent out of what happened. Any creation of a narrative is a bit of a lie. And some lies have enough truth” (qtd in Heritage Day: The Importance of Life Stories).

For our purposes in a writing class, it is paramount that we tell meaningful and coherent stories. Meaningful so that we are invested in communicating something to someone who may or may not know us; coherent so that our story can be understood. And while this conversation of truth and memoir can get a bit theoretical, it also has a very practical and pragmatic impact on writing memoirs.

Let’s return to the short vignette between me and my student to see how we worked through her decisions concerning her memoir:

After that conversation her story took off:

We would drive up the canyon in his VW bug van. He wore his old fishing hat and I wore my scuffed-up sneakers. We would stop at the mouth of the canyon. The air was still crisp and fresh. Before getting out he handed me a small Tic-Tac box that said orange on it in bright colors. In my young mind it seemed odd that once where there were yummy orange candies now there would be gross little grasshoppers spitting black juice. After getting out of the car I would take his hand until we reached a dry place where many grasshoppers were jumping, “Go to it,” he would say and then he’d move off to another spot where he would fill his Tic-Tac box. After ten minutes or so he would return asking, “What did you find?” I was so proud of my catch, so proud that I had braved the sticky little legs and black juice.

MAKING DELIBERATE CHOICES

She also reflected on her process of figuring out the details:

I couldn’t remember what kind of car exactly that he drove so I asked my mom. I drove up to the canyon where I knew we had fished, hoping I would remember more details about our trips. Driving up I remembered how we used to stop at the mouth of the canyon to catch grasshoppers. But that’s all I remembered. I did know that the overall experience was positive. He was a father-figure to me and I felt safe and confident. So I made up the other details to communicate this. To help me with some details I looked up images and videos of grasshoppers and people catching grasshoppers. That’s where I got the black juice idea, which I had forgotten, but I’m sure must have been there.

True stories, even when told through the genre of memoir, are about much more than simply transcribing each fact. We may still have to do some research by talking with others and looking up details. But this process, as we see above, is not about sticking to the facts. Instead, it is about the overall emotional truth and getting, as best we can, at the experience of being human.

Writers, therefore, have to make deliberate choices about what kinds of truth their stories contain and how they then choose to communicate these truths.

Works Cited

Paterson, Katherine. Bridge to Terabithia. New York: Harper Trophy, 1977. Print.

“Theories of writing and composition pedagogy.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., date last updated. 17 July 2014. Web. Date accessed 03 March 2016.

“Heritage Day: The Importance of Life Stories.” The South African College of Applied Psychology. 21 Sept 2015. Web. 15 Feb 2016.