Unpacking the Process of Rhetoric

Tiffany Buckingham Barney

Rhetoric is confusing. There. I said it. That elephant has been in every room of every English class focusing on rhetoric I’ve participated in, whether that be as a student, an observer, or an instructor (although I’m certainly happy to address that elephant in my classes). The problem with rhetoric is that it is just so much to unpack. Much like Mary Poppins’s bag that seems to contain anything and everything, some of which are seemingly impossible to fit inside, the idea of rhetoric has so much discussion going on inside that it seems that bag will never be unpacked, and maybe it won’t, but for our purposes―for your purposes in a basic English class―let’s keep things simple.

RHETORIC IS A PROCESS

Although it can appear magically full of the impossible-to-comprehend, the overall notion of rhetoric can be simplified by breaking it down into the smaller terms associated with it. When doing so, it helps to look at the terms’ relationships with one another and consider it a process.

Just like any other process, there is a desired outcome for using rhetoric. Think of it: the desired outcome of cooking a meal is a meal, of hair restoration is a full head of hair, of making TikTok videos is … yeah, who knows the desired outcome of those? In the case of rhetoric, according to Aristotle (the guy who opened the bag in the first place) the desired outcome is persuading the audience. Persuasion, in a rhetorical sense, means more than convincing. Benjamin Solomon, another Open English author, claims that “all good writing is persuasive.” In his piece, “The Persuasion Effect: What Does It Mean to Write Persuasively?” Solomon connects Aristotle’s idea of persuasion to the idea of writing intentionally.

That act of persuading is a natural process. Aristotle didn’t just make up some random process and expect writers to use it; he explored a process and described it. The process was already happening; he explained it. Now, let’s jump ahead a couple thousand years and explain it in the 21st century by unpacking some of the terms one piece, or one step, at a time.

Use Rhetorical Devices ⇛ to Elicit Rhetorical Appeals ⇛ to Deliver a Rhetorical Argument

You use rhetorical devices regularly without even realizing it. When you tell a friend a story or answer a question in class with reasoning you’re using the rhetorical devices of storytelling (narrative) to talk to your friend and reasoning to answer the question. Similarly, metaphors and idioms are so commonplace that they have a whole subcategory called cliché. Examples of idioms gone cliché: the cat’s out of the bag; you can’t have your cake and eat it too; don’t judge a book by its cover; I didn’t just fall off the turnip truck―okay that’s probably only a cliché at my house just because it’s so funny.

Just like you use rhetorical devices regularly in speaking, you are likely to use them in writing without even realizing it. However, clichés are frowned upon in academic writing for the most part, but as they say, even a stopped clock is right twice a day. (Was that another cliché?)

The list of rhetorical devices is not exhaustive because we use so very many different ways to get our point across. Of course, Wikipedia has a list of rhetorical terms, most of which are rhetorical devices and, as with all things Wikipedia, people are adding to this all the time. Like a dictionary though, including everything is quite the task.

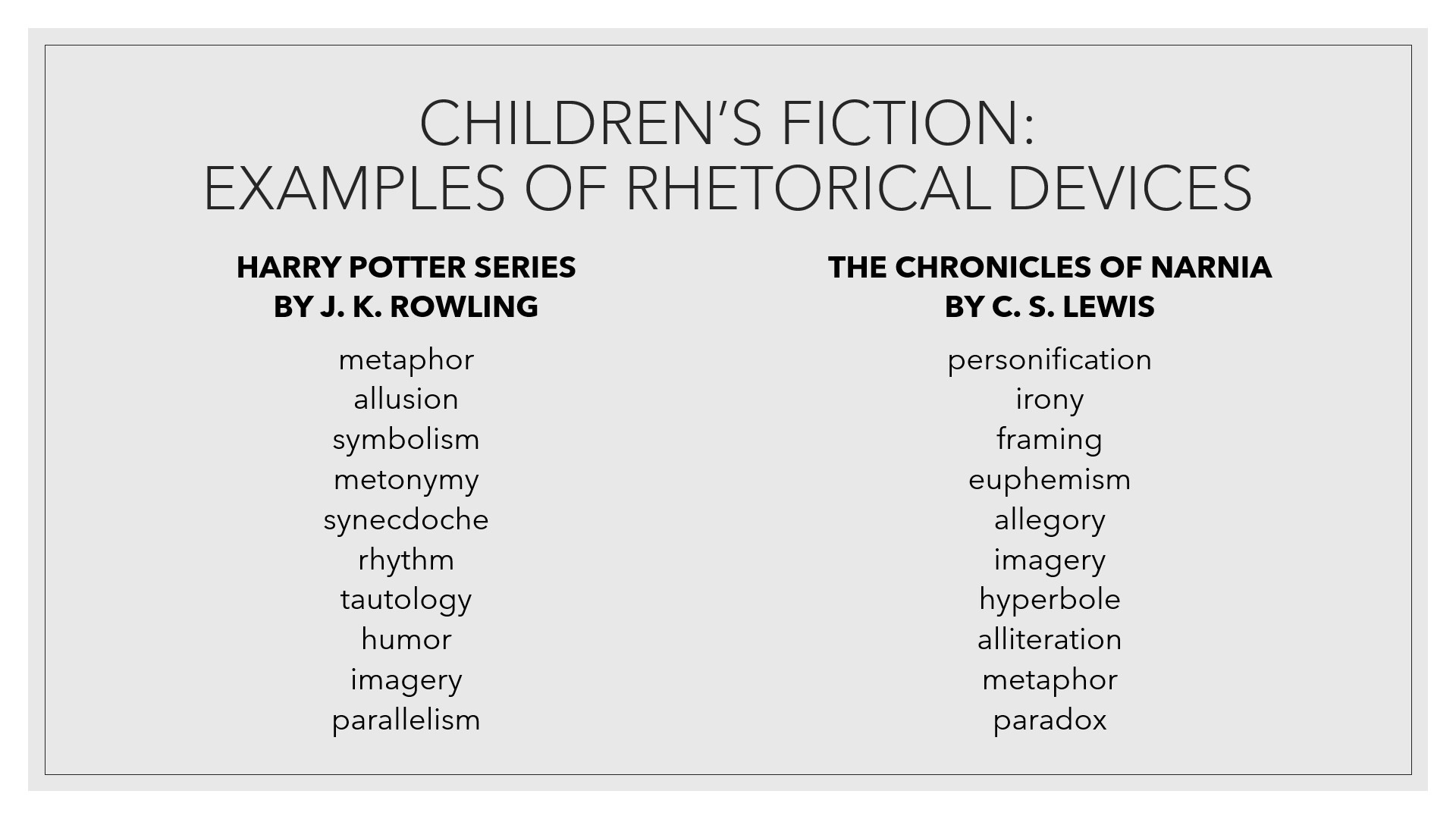

One of the skills of an accomplished writer is to use rhetorical devices purposefully. Some of my favorite children’s authors use metaphor rather heavily along with multiple other rhetorical devices (each worth a quick Google search). We’ll use children’s authors since we all know they’re the best, because come on, personification?! Who doesn’t love the lion, Aslan, talking to the children? We’ll also use children’s authors because one type of rhetorical device is literary device and, although those show up in other forms of writing, they really just scream out in fiction literature. The visual symbolism of Harry Potter’s scar is imagery that’s difficult to miss.

USE RHETORICAL DEVICES ⇛ TO ELICIT RHETORICAL APPEALS ⇛

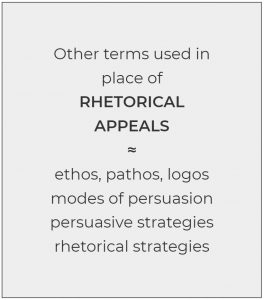

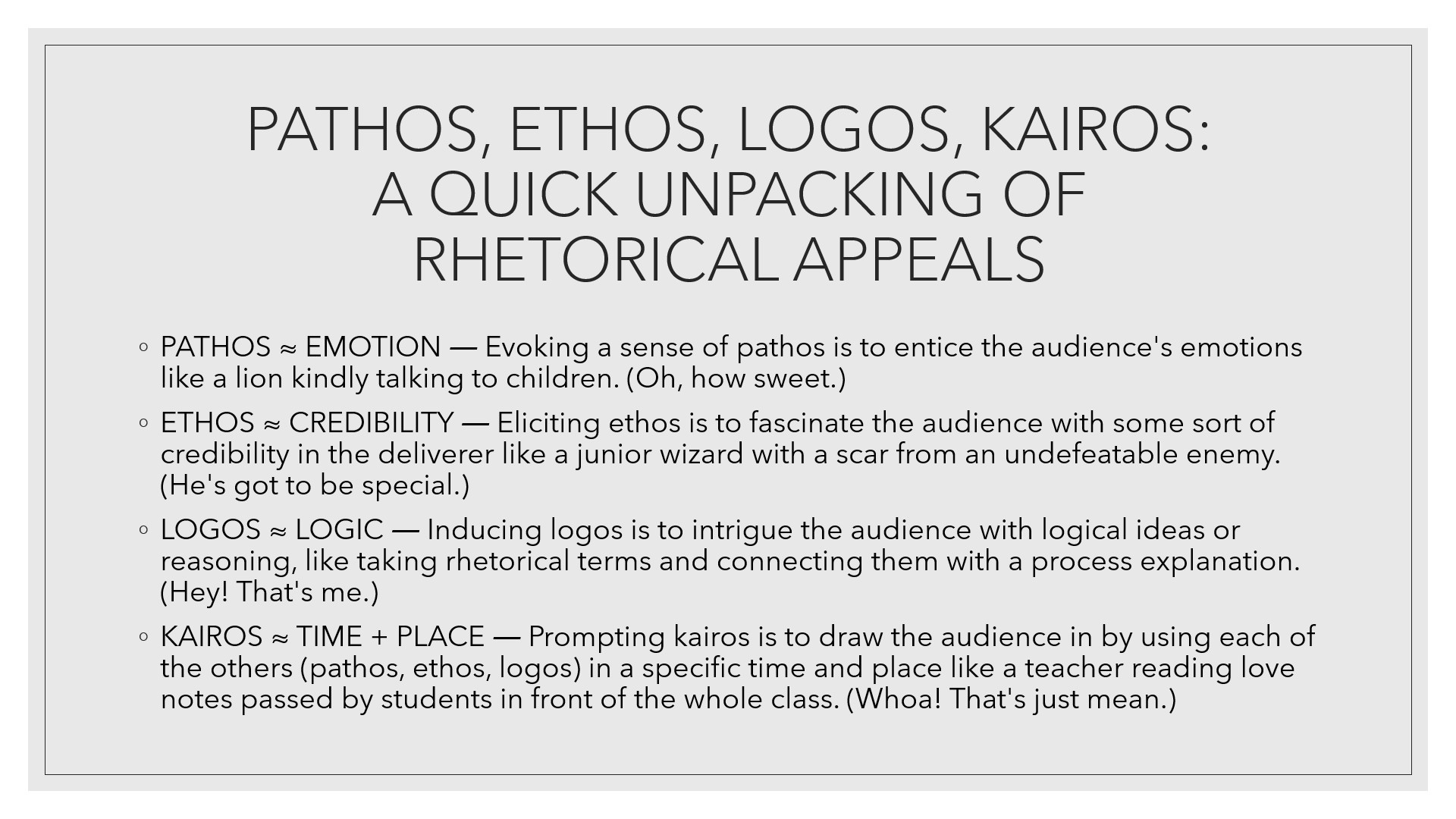

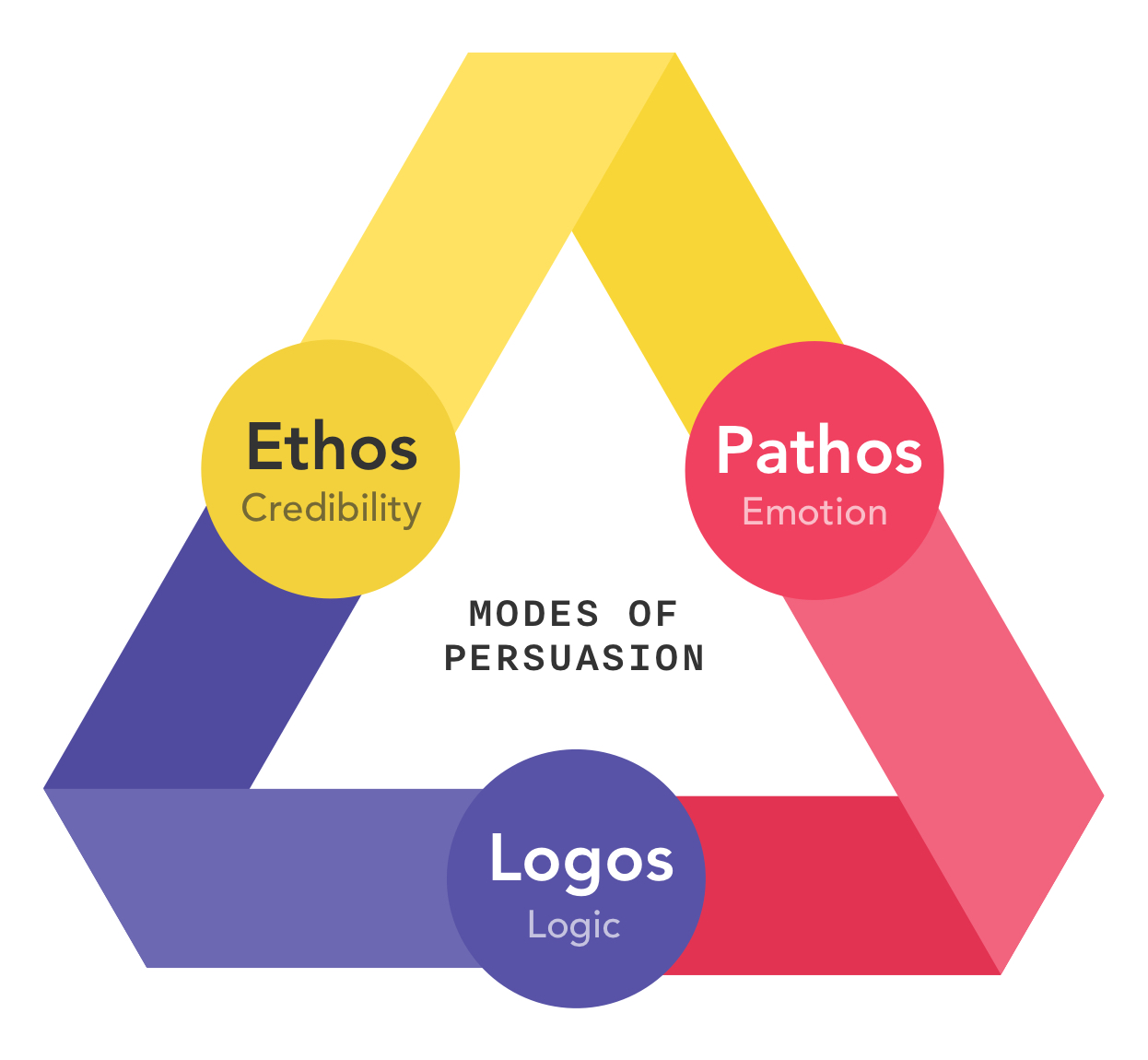

This list is exhaustive. The three main rhetorical appeals are words you may have already heard: pathos, ethos, and logos. There’s a fourth rhetorical appeal that’s sort of the third wheel of rhetoric or fourth wheel because there’s already three. Oh! It could be the fifth wheel because it’s so useful. It’s kairos and it’s not discussed every time rhetorical appeals are. All of these are referred to as appeals because each of them refers to a different way the audience was influenced.Use rhetorical devices like metaphor or personification or symbolism to draw out different senses in your audience. Those senses are rhetorical appeals.

The rhetorical triangle is the common image to display the three rhetorical appeals. Notice the spare tire (kairos) is missing here and in every rhetorical triangle because it has to do with the application of the other three. Reading love notes makes students embarrassed (pathos) by the teacher (ethos) for not spending class time on class work (logos). Doing it in front of the class, during class, is what fueled it all (kairos). Maybe kairos should just be a huge flame all over the triangle.

Keep this triangle in mind to keep the idea simple. Rhetorical devices are used to bring about these three appeals (and also bring into play the fourth).

USE RHETORICAL DEVICES ⇛ TO ELICIT RHETORICAL APPEALS ⇛ TO DELIVER A RHETORICAL ARGUMENT

By using rhetorical devices to draw out those rhetorical appeals in the audience, the author delivers the overall rhetorical argument of the piece. Rhetorical argument is not the same as the disagreement at last year’s Thanksgiving about whether Die Hard should count as a Christmas movie or not. Having an argument and delivering an argument are two different things.

By using rhetorical devices to draw out those rhetorical appeals in the audience, the author delivers the overall rhetorical argument of the piece. Rhetorical argument is not the same as the disagreement at last year’s Thanksgiving about whether Die Hard should count as a Christmas movie or not. Having an argument and delivering an argument are two different things.

Arguing, in the sense of rhetoric and according to Aristotle (remember, the guy who opened the bag), is convincing your audience or using the art of persuasion to convey ideas. So, write an entire essay or give an entire speech about the Christmas qualities of Die Hard, but stop yelling the same thing over and over and definitely stop throwing mashed potatoes.

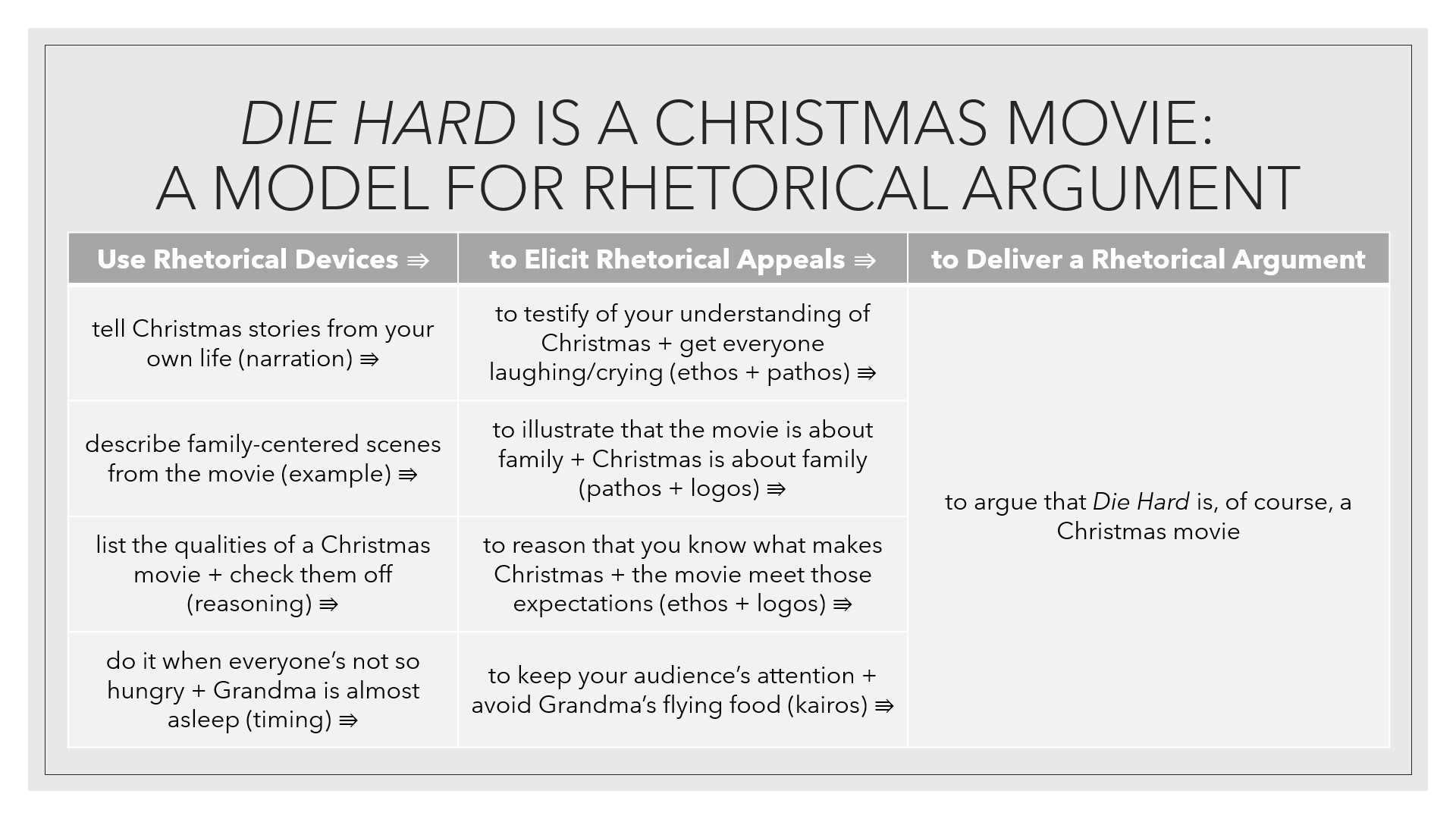

The rhetorical argument is really the main idea of the speech: Die Hard is, indeed, a Christmas movie. It’s the idea the author is trying to convey or what the author is trying to persuade the audience to believe. This is the overall goal accomplished by speaking or writing and it’s done by appealing to the senses of pathos, ethos, logos, and that other wheel (or flame), kairos.

All of the above is accomplished by using language tools and, therefore, using rhetorical devices. The speech is likely to use more rhetorical devices than those listed in the table, but the table is a good start. Notice too that rhetorical devices can evoke more than one rhetorical appeal. All of them, however they’re laid out, should lead to the same end argument.

This is just one way to accomplish the overall task of convincing a crowd that Die Hard is a Christmas movie. Other rhetorical devices could be used in different ways in order to elicit the rhetorical appeals and therefore make the argument.

So, here’s the lesson, in order to effectively argue that Die Hard is a Christmas movie or to effectively argue anything for that matter one should…

Use Rhetorical Devices ⇛ to Elicit Rhetorical Appeals ⇛ to Deliver a Rhetorical Argument

ANOTHER TERM TO UNPACK: RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

Now a few terms from our bag are unpacked and neatly folded ready for use: rhetorical device, rhetorical appeals, and rhetorical argument. This is not the end of the explanation of rhetoric. Remember Mary Poppins keeps pulling more remarkably large items out of her bag? There’s another set of terms associated with rhetoric under the category of rhetorical situation that’s unpacked in a different Open English article by Justin Jory, called, rather unsurprisingly, “The Rhetorical Situation.” Also, another Tiffany, Tiffany Rousculp, introduces the terms rhetoric and genre rather simply in her Open English piece, “Rhetoric & Genre: You’ve Got This! (Even If You Don’t Think You Do …).” There are a myriad of other terms associated with rhetoric, several of which are somewhat interchangeable.

Another term that will come up in basic English classes is rhetorical analysis. Now that you understand (well, hopefully) the process of rhetoric, it can be easier to write your own analysis of how another author used the process effectively or not. You, the audience, could write a rhetorical analysis of the Harry Potter series, The Chronicles of Narnia, a teacher reading a private note in front of class, someone else’s speech of why Die Hard is a Christmas movie, or just skip the speech and analyze the movie itself. In each of these cases, you, as the audience, and now the author of the analysis, would evaluate whether the author/educator/speaker/movie maker effectively used rhetorical devices to appeal to the audience’s sense of pathos, ethos, logos, and kairos to deliver the message or not.

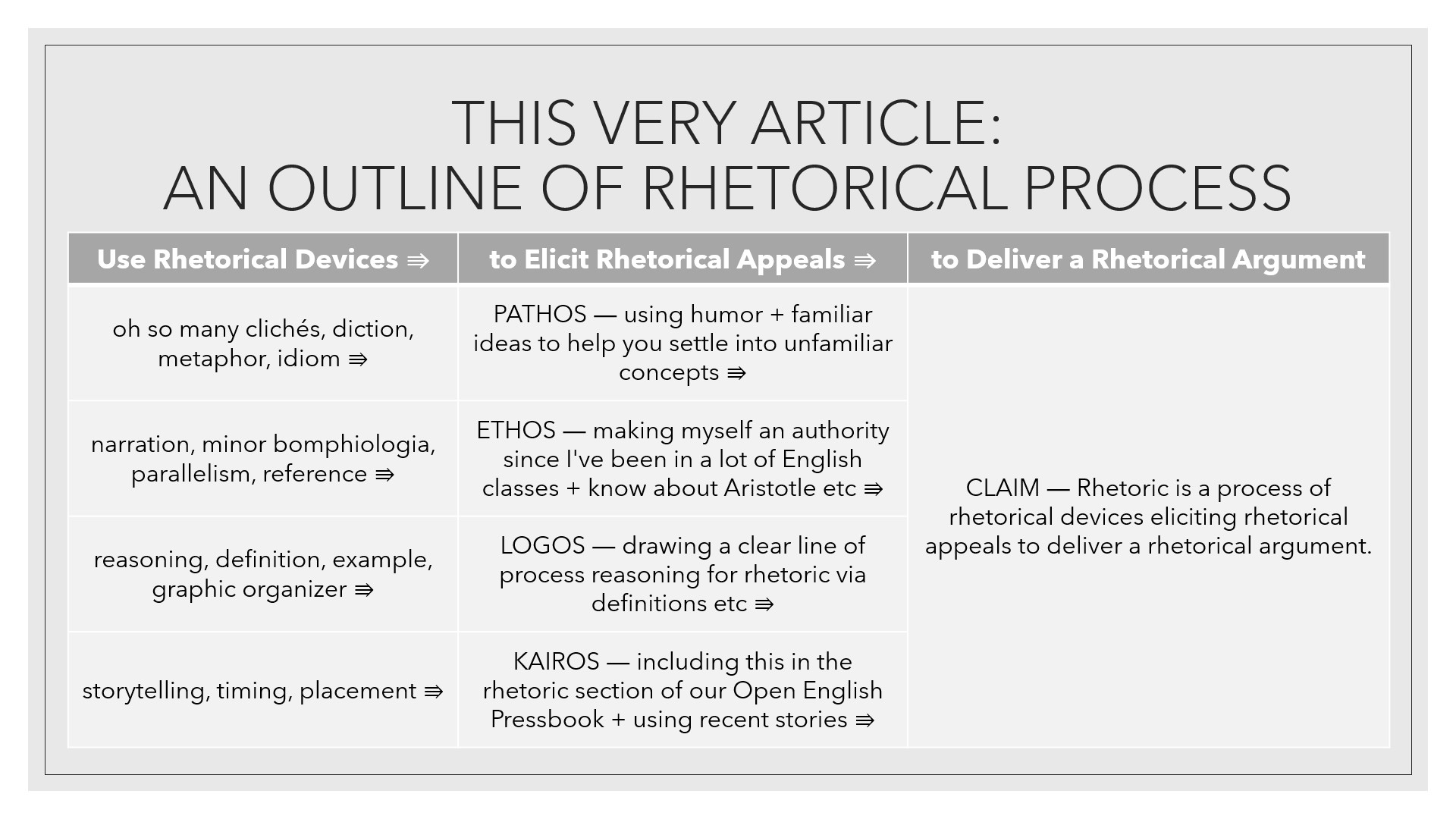

This very piece, written by me, used the process of rhetoric.

You, the audience, are welcome to do a short rhetorical analysis of my piece on paper or in your head. (After all, I already did the outlining of ideas for you in the table above.) Essentially, a rhetorical analysis is asking the questions:

How does the author of the piece you’re analyzing …

Use Rhetorical Devices ⇛ to Elicit Rhetorical Appeals ⇛ to Deliver a Rhetorical Argument

… and how successful are they? How successful was I? That’s up to you, the audience.

Bibliography

Christopher, Joe R. “An Introduction to Narnia Part IV: The Literary Classification of The Chronicles,” (1973) Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature, Vol. 3 : No. 1, Article 3. dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol3/iss1/3. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020.

“Glossary of Rhetorical Terms.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Nov. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_rhetorical_terms. Accessed 11 Dec. 2020.

Jory, Justin. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Open English @ SLCC. Pressbooks, 2016. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/the-rhetorical-situation/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2020

Nilsen, Don L. F., and Alleen Pace Nilsen. “Naming Tropes and Schemes in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Books.” The English Journal, vol. 98, no. 6, 2009, pp. 60–68. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40503461. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020.

Rapp, Christof. “Aristotle’s Rhetoric.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2010/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020.

Rimstidt, Aaron, and Post Editors. “The 10 Silliest Clichés Since Sliced Bread.” The Saturday Evening Post, 28 Mar. 2012. www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2012/04/silliest-cliches-sliced-bread/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2020.

Rousculp, Tiffany. “Rhetoric & Genre: You’ve Got This! (Even If You Don’t Think You Do …).” Open English @ SLCC. Pressbooks, 2016. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/rhetoric-genre-youve-got-this-even-if-you-dont-think-you-do/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2020.

Solomon, Benjamin. “The Persuasion Effect: What Does It Mean to Write Persuasively?” Open English @ SLCC. Pressbooks, 2016. openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/the-persuasion-effect-what-does-it-mean-to-write-persuasively/. Accessed 11 Dec. 2020.