That’s All I Have to Say! Writer’s Block, Invention, and Revision in the Writing Process

Brandon Schembri

Have you ever found yourself staring at a blank computer screen? And you wait. And wait. Go to the refrigerator. Come back. And wait. And wait? After a while you forgot what you were waiting for. At some point you may wonder why you signed up for this English class in the first place! Well, rest assured, the symptoms you are describing suggest writers block, and it happens to every writer. And it’s normal. But this may be something you can relate with:

Let me illustrate another way.

Several years ago, I was working at the boys and girls club on Salt Lake City’s west side. My task was to facilitate a writing workshop for young teens ― an after-school program of sorts. Around a large table were several early teenage kids and me. I was there to teach writing. Halloween was a week away, and we were doing a short story about goblins, ghouls, and other freakish monsters. One boy in particular, with blonde hair and steel-blue eyes, I remember, was not getting into the assignment. He was writing on the table, distracting other kids, doing anything he could to not write. I walked over and discovered he had only a few short sentences. So, in attempts to curve his energy back to the task, I leaned over and asked: “Looks like you have some interesting sentences there.” He scoffed in response and kept trying to play with the boy next to him. Then, remembering that open-ended questions often prompt new thoughts or discoveries, I inquired: “What else can you say about this monster you wrote about? What were his eyes like? Or his hands? Does he growl?” I waited a few moments, hoping to get his mind jogging.

After a few moments of this questioning, the boy, flustered and frustrated, looked me in the eye with his steel-blue eyes and said angrily: “That’s all I wrote ’cause that’s all I’s got to say!” I had been reprimanded by a 13-year-old. He had used up his reservoir of words and was done.

It was kind of like Forrest Gump, from the movie Forrest Gump:

This student did not have a writing process to rely on. He wrote what was in his mind, then stopped. In this article, instead of stopping, we will be exploring several areas of the writing process. By the end of this article, you should be able to

- explore what the writing process is,

- understand how professional writers use the writing process,

- discover your writing process,

- find solutions for jumpstarting your writing process,

- and save a writers toolkit (resources) for future use.

In essence, the writing process is a method of discovery. Even the most seasoned writers have committed to a process. The process is individual, after all. And you’ll notice that even your assignments and essays can help you discover your process as a writer. It will pay dividends in the long run ― by helping you know how you tick.

THE WRITING PROCESS

College students are like the young boy I mentioned earlier, marching into an English classroom and realizing this may be a little over their heads. Or perhaps thinking, “I really don’t know how to write that.” Hopefully, your vocabulary, patience, and maturity have expanded, and you are not in the same circumstance as my youthful counterpart.

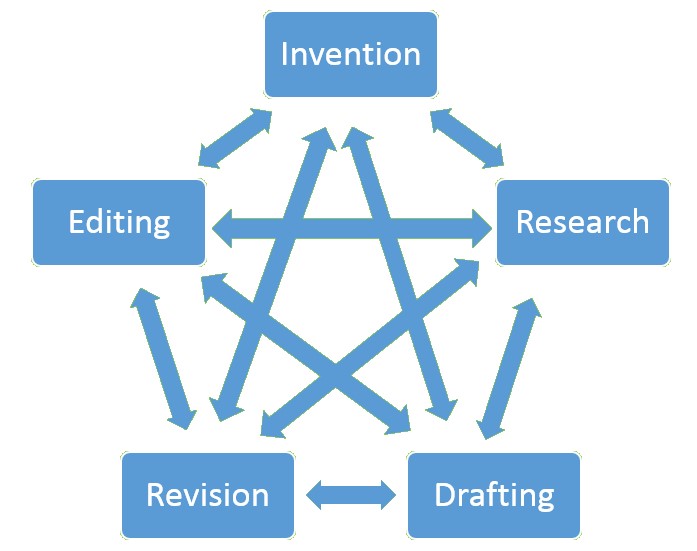

A good article that offers play as a method of unwinding from that mental space is “Writers Block? Try Creative Play and Freewriting,” found right here in Open English @ SLCC. And let’s borrow an image from “Writing Is Recursive,” another chapter in this textbook, to illustrate my next point:

The graphic shows that writing is recursive — which means each step can be used repeatedly, in any order. Typically, writer’s block comes with the drafting part of the process. Often revising what is already written or going back to the invention stage is what is needed to “get out” of the mental stalemate. Meaning: the writing process does not need to start with brainstorming and end with editing. For example, you could start with the middle (or what you expect to be the middle of your paper) and write (drafting), then start researching your topic. Or another example: revise an old paper to see if you notice any differences from when you wrote it until now, then draft. The point is to develop a writing practice.

But then you say, “Wait! What does this have to do with finishing my paper?”

Here it is: Writing is recursive. Remember that as we go on.

BIG IDEA: Writing is recursive.

EXAMPLES OF WRITERS AND THEIR PROCESS

All writers, even the professional ones, have a process in which they write. They trust in the process, and as a result they can produce. Look at the writing process as a method of discovery. How do other writers do it? Let us look at a few of them, courtesy of Literary Hub (Temple). Some of them you may know, and others you may not.

Each writer, however and wherever they write, has committed to a writing process ― a creative process that allows them to overcome some of the pitfalls of writing. You can use a process too. See what works well for you as you go throughout this semester. In the next section there is an informal mini-test that may help you articulate your writing process.

BIG IDEA: Writers commit themselves to a creation process ― a writing process.

STUDENT PROCESS ― A QUICK TEST

These questions are not designed to be total and definitive, but they can give you a good sense about your style and preference when it comes to writing. Remember, this is about overcoming writing obstacles through the writing process.

Answer the following questions on a separate piece of paper or think through them:

- What time of day do you write the best? Mornings, afternoons, evenings?

- Is there a time of the week that is ideal? Monday before everything gets started? Friday/Saturday?

- What texts (pieces of writing) do you tend towards and why? What does that say about your tastes and style as a writer?

- What is it that you dislike about writing the most?

- Are there times when you are inspired to write? Describe the instance.

- Are there times you definitely do not like to write?

- Do you prefer to type or write by hand?

- Do your ideas on what to write come on the go or in a deliberate, planned, and concentrated space?

- Do you like just one or multiple people giving you feedback for revision?

- Are you one to go back and adjust/revise a piece of writing, even multiple times?

- Are you more structured (need a plan) before you begin or go with the flow?

- Do you tend to think in shapes or words when prewriting strategies?

- Do you enjoy drafting in a public or private space?

- Do you like working alone or collaboratively on writing projects?

Hopefully some of these questions will make you aware of your process as a student and writer. Part of your experience at SLCC is to determine how and when you are most effective and productive ― which leads to another point that your writing process is individual and creative.

BIG IDEA: The writing process is individual and creative.

SOME SIMPLE IDEAS FOR JUMPSTARTING YOUR WRITING PROCESS

Now that you have taken a brief test, here are some solutions for you. I have found that students either really enjoy planning or do not particularly fancy structured methods. Regardless of your preference, there are solutions for any writer. Figure out which works best for you. Remember to check out the writer’s toolbox below for more ideas on organization and learning strategies.

Like planning? Try these:

- Map out on your calendar planning time, drafting time, and revising time ― dedicate the time, and your brain may make connections for you while the deadline approaches for each phase.

- Start with the end in mind: how do you see your piece ending or impacting someone?

- Create an outline with structured bullet points that compliment and expand on each other.

- Try using mind maps or word webs (see toolbox below).

- Write in chunks. Do the beginning one day, the body on day 2, and conclusion on day 3.

Not the planning sort? Try these:

- Draw the concept.

- Use Venn Diagrams ― are there any overlapping concepts among your many thoughts and ideas?

- Pick a special spot on campus (or at home) and make it your writing spot ― your place of inspiration.

- “Feel” your way through a text or an essay. Many writers just know that they have arrived at something. Maybe apply this rule of thumb: if you do not like it, they (the readers) won’t like it. Arguably, this skill is sharpened and realized with practice.

- Craft from the middle of the essay and work your way out.

- Sing the concept.

For anyone, try these:

- Start writing ― I have found this to be most practical. Just start, write anything, and see what comes.

- Explain or teach your ideas to a friend/family member.

- Tell your dog about the paper.

- Go for a walk or walk the dog.

- Talk to a friend ― get your mind off the topic you are grappling with. Oddly enough that frees up your mind to explore undiscovered connections.

- Write, then sleep on it.

- Know when to stop ― this is important.

Try some of these and see if you find something that clicks. To reemphasize what was mentioned earlier, the writing process is an individually tailored method of discovery. Authored by you. Use it as such. The best writers have figured out how to write, even under an impending deadline. Really this is all about you and your process. The quicker you discover it, the better you will be able to manage your many writing assignments. Also, it is important to know when to stop and put your writing away. The process does end. So, wrap it up and know you have done well.

I go full circle, to the young boy at the table mentioned earlier: while his reservoir of words or writing may have been used up, there may have been more that I could have done. Here is what I wish I would have done: asked the young boy to draw a picture of the monster or use construction paper, scissors, and coloring tools to decorate the monster he had envisioned in his head. Permitting him that mental disconnect, or redirection, could have allowed him to further elaborate with words. Essentially, helping him make his own writing process. And who is to say you cannot use scissors and tape? After all, it may just be part of his process. And that is all I’ve got to say about that!

WRITER’S TOOLKIT

Try these other Open English @ SLCC chapters for more ideas:

“Writer’s Block? Try Creative Play and Freewriting”

“A Quick Introduction to College Learning Strategies”

“Organizing Texts in English Academic Writing”

Works Cited

Temple, Emily. “12 Contemporary Writers on How They Revise.” Literary Hub, 10 Jan. 2017. lithub.com/12-contemporary-writers-on-how-they-revise/.