Rhetoric & Genre: You’ve Got This! (Even If You Don’t Think You Do …)

Tiffany Rousculp

It’s your first day of your first semester of college. You settle into an uncomfortable seat in a fluorescent-lit room, glance around at other students hypnotized by their phones, and wait for the teacher to begin. The LCD projector hums above as it warms to display the syllabus and the teacher begins to talk:

“Welcome to English Composition. In this class, you’ll learn about rhetoric. We will learn how to use genre to navigate different writing situations …”

Hmm. You thought this was a writing class.

Rhetoric? Genre?

Am I in over my head?

Not to worry. You’re totally fine. You’re in the right place. These terms, rhetoric and genre, are words that may be unfamiliar to you, but you already know a lot about what they represent.

Rhetoric and genre are, at the same time, very simple and very complex concepts. There are other excellent readings in the Open English@SLCC collection that share their complexities with you, like Lisa Bickmore’s “Genre in the Wild” and Lynn Kilpatrick’s “Definitions, Dilemmas, Decisions”; but for now, let’s start simple. Let’s start with what you already know.

RHETORIC & GENRE POP QUIZ

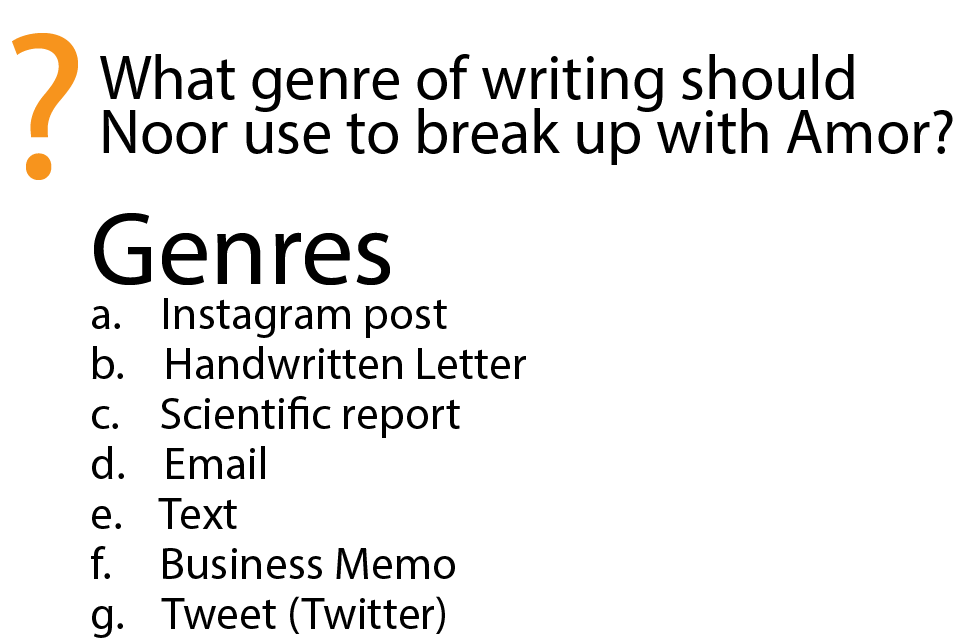

Your friend, Noor, has been in a romantic relationship with Amor for the past two years. A few months ago, Noor moved to another city and, after trying to have a long-distance relationship, has decided to break up with Amor. Noor wants to break up in writing because they are scared that they won’t be able to go through with it in person (or over the phone) because Amor will talk them out of it. Noor still loves Amor and wants this to be as painless as possible for both of them.

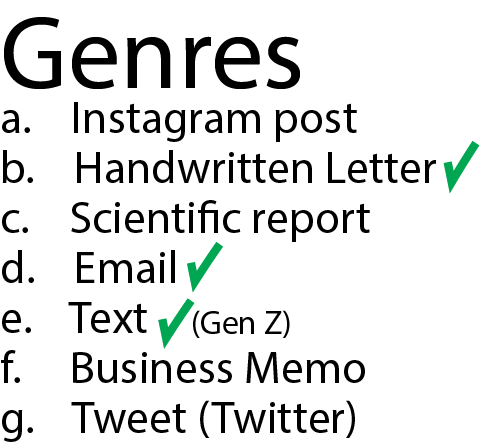

If you answered B or D, you are in agreement with nearly everyone else who has ever or who would ever take this quiz. (If you answered E, you’re probably from Generation Z, but let’s see what you think by the end of this reading. You might change your mind.)

That was a pretty easy Pop Quiz. And your response shows that you already are quite skilled at using rhetoric and genre. Sometimes encountering new words (i.e. vocabulary), like those found in a syllabus, can make you feel insecure or unsure of your abilities. That’s normal. There are steps we can take to move past those feelings so you can get started learning.

UNDERSTANDING NEW WORDS

First, let’s look at those words.

rhetoric [REH · tr · uhk] Middle English: from Old French via Latin from Greek, ‘art of speaking or writing effectively’

At its most basic, in terms of reading, writing, and English composition classes, rhetoric is the analytical study of communication. In composition, that communication tends to consist of print, digital, visual, and sometimes audio documents and texts. (Rhetoric is also used to study spoken texts as well, but that tends to happen more in communication classes.) Rhetorical analysis asks you to examine texts in terms of purpose, author, audience, and context (or situation).

genre [ZHAAN · ruh] early 19th century: French, literally ‘a kind’

Genre is one element of rhetoric. Genre, in its most basic meaning, means “a type, or kind” of text. Texts can be described as, or categorized into, genres. The effectiveness or appropriateness of a specific genre of text depends on the situation in which it is occurring.

Next, let’s take these definitions to analyze how you came to your decision about what genre Noor should use to break up with Amor.

COMPLEX RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

You may not believe this, but your brain conducted a complex rhetorical and genre analysis to come to your decision. It may have only taken a second or two, but you and your brain sorted through all of the elements of rhetoric to make a pretty solid decision on which was the most appropriate genre.

Here’s what your brain did, though not necessarily in this precise order.

Considering the entire situation, your brain noticed who the author was (Noor) and who the audience was (Amor), and what kind of relationship they had: romantic, long-term, now long-distance, and they still love each other. You noticed that the author had a specific purpose for writing: to break up.

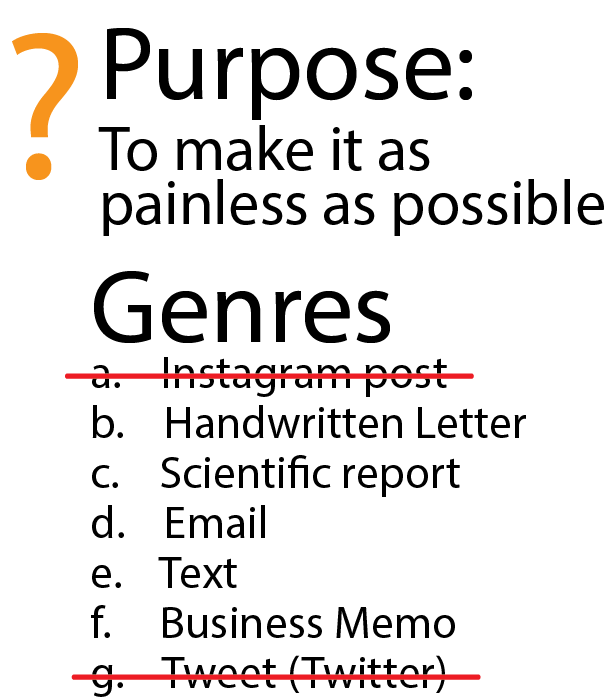

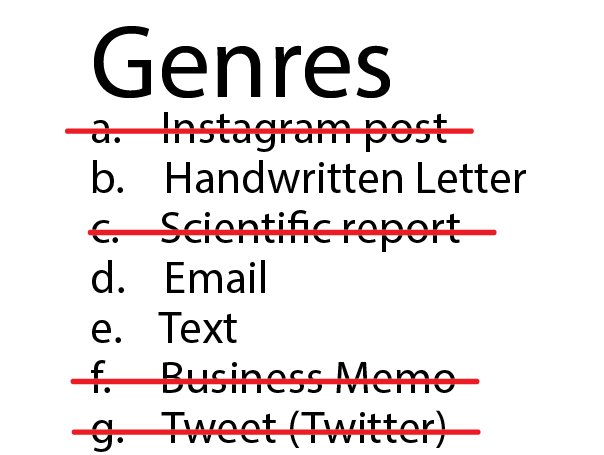

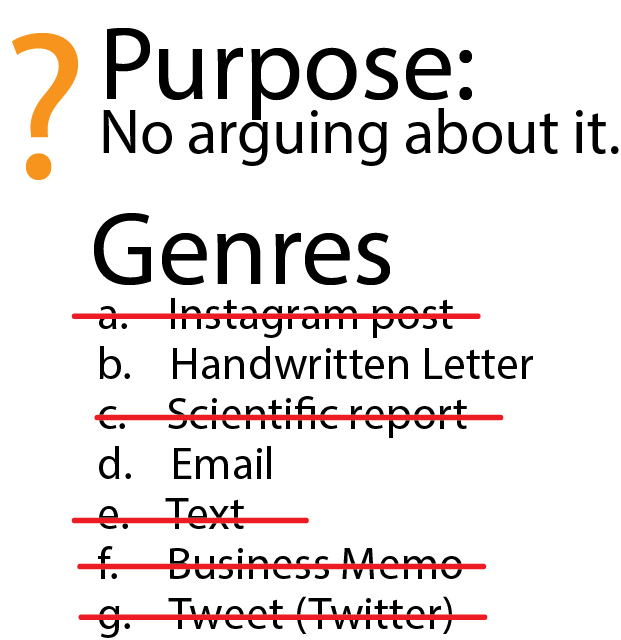

Then, your brain noticed that the author had another purpose (to make it as painless as possible). With this in mind, your brain eliminated public genres (Instagram posts or tweets) because it would be cruel to do something so private and emotional with another audience watching.

Your brain probably paused for a moment when it noticed the scientific report and the business memo genres because they were unexpected; you may have thought they were funny or strange, but then discarded them as realistic options.

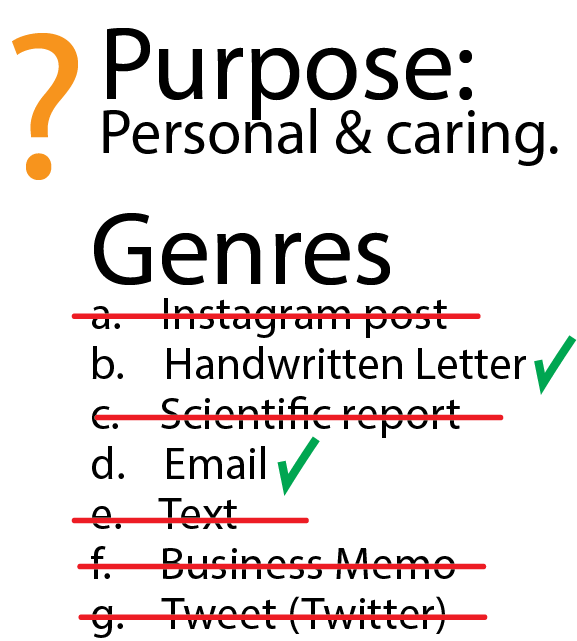

With three genres left, your brain re-analyzed the author’s purpose to look for possible ways to eliminate any of them. You noticed that the author was afraid that the audience would try to argue against the break-up. Knowing that having a real-time conversation is more likely in texting than through email (and impossible in handwritten letters), your brain turned to the final two options.

So which one? A handwritten letter or an email?

Your brain likely went through another round of rhetorical analysis: A handwritten letter may have felt more personal and caring, which would have been a good choice considering one of author’s purposes. But, a handwritten letter, in this digital era, could come across as more distant, which could feel cold and uncaring. Your brain may have wanted more information about the author and the audience, but the situation didn’t provide it. Because of this, you may or may not have come to a strong decision on which genre was best to use.

Your brain did all of this, and it did so very, very quickly. Your brain is an extraordinary rhetorical and genre analysis machine.

The terms rhetoric and genre, and others that often go along with them, can feel intimidating when you encounter them, and it will likely take some time for you to feel confident using them to analyze texts, and to produce your own. Until you get there, remember that your brain is already doing rhetorical analysis work, all the time, whenever you are in a situation that involves communication.

Your task is to pay attention to it. Take notice when you make a decision about your writing based on who you (author) are writing to (audience), or why you are writing (purpose), or the circumstances of your writing (context/situation), or what “type or kind” of writing you thought would be best to use (genre). You make dozens (or hundreds or thousands!) of large and small decisions each time you write, regardless of whether it’s an essay for a college class, a text to a friend, or a late-night journal entry to yourself. Your brain is doing the work. Watch closely and you’ll see.

Rhetoric? Genre?

You’ve got this. You really do.