Open-Ended Conversations: Moving Beyond “Pro” and “Con” and into Inquiry

Tiffany Rousculp

- Summary

- How We Talk About Argument

- How Common Are Binary Arguments?

- They’re What We Learn in School

- And Then, College Happens

- College: An Inquisitive Space

- College = Inquiry = Research

- College Students Have Inquiring Minds, Too

- Open-Ended Conversations

- Scholarship: Inquiry on Steroids

- Inquiry and Open-Ended Conversation in ENGL 2010

Summary

There are three things every college student needs to know in order to progress from entry-level reading and writing skills to more advanced reading and writing in your 2000-level classes and beyond:

- Open-ended thinking is the basis of learning in college.

- Inquiry leads to open-ended thinking and conversations.

- In college, argument is formed through inquiry.

Outside of college, we often talk about argument in simple terms. On news programs, controversial matters are frequently debated by two guests with opposing views. In high school, you learn to write essays that ask you to take one side and show it is better than the other one. On social media, opinions and people are grouped into “for” or “against” something, so much so that it has become difficult to talk to people who may feel differently than we do about any number of issues, like climate change, animal rights, gun control, immigration, artificial intelligence, or social media.

This way of framing argument is considered a binary division of opinion or perspective.

“bi-” means “two”; “binary” means “two-sided”

Common issues that turn into binary arguments include: “Does social media harm mental health?” “Should taxes be raised on high income earners?” “Should higher education be free for low-income students?” Framing an argument with a question that asks for a “yes” or “no” response tends to lead to binary thinking, which limits the possibility of further conversation.

Binary arguments are the most common types of argument made on the news, in the public realm of politics[1], and on social media. For example, the U.S. Constitution’s Second Amendment’s “right to bear arms” is an extremely complex issue, but it is publicly debated as having only two possible options. Two-sided arguments get our attention because they confirm that our opinion is right—or tell us that we are wrong. They are deceptively simple, so it’s easy to feel like we know enough to think our opinion is the correct one. These qualities of binary arguments draw us in and keep us coming back for more: binge-watching the news, complaining about the corrupt politician, clicking on the latest post. Because of this, two-sided arguments are a money-maker for media companies and political campaigns, so they’re understandably motivated to keep things the way they are.

Framing argument as two-sided—or pro/con—surrounds us in our public lives, but we are also taught the same thing in school before we get to college. In the U.S., students learn to make arguments as early as elementary school by writing persuasive essays that follow a specific structure:

- Introduction with thesis

- Paragraph #1

- Paragraph #2

- Paragraph #3

- Conclusion

- Introduction paragraph and your thesis

- First argument for your thesis

- Second argument for your thesis

- Argument against your thesis and your response to it

- Conclusion

Certainly! Here’s an outline for a persuasive argument essay.

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

a. Present the main argument and supporting evidence

b. Address counterarguments (opposing viewpoints)

c. Present additional supporting evidence - Counterarguments and Rebuttals

- Conclusion

Notice the words used: “counterarguments (opposing viewpoints).” If you participated in debate, or if your teacher(s) assigned you to debate in class, you were likely divided into “pro” (for something) and “con” (against something) groups. Maybe you were allowed to pick what side you were on, or you were assigned the side that you didn’t agree with (or maybe it was a surprise). Either way, you had one of two positions that you had to argue for, and the other was to be argued against.

There are good reasons for teaching young students to make arguments in a binary manner. First, two-sided arguments are simple. It is much easier for a young brain to grapple with two options than to try to understand ten. It also takes time for young people to develop empathy, to realize that other people may have valid reasons for having different opinions than they do. Providing a structure of “pro/con” creates a way for students to think outside of themselves while their brains are maturing.

You are surrounded by binary thinking about arguments in the public sphere. You learn in school that the way to make an argument is to do so in a two-sided manner. You certainly know that arguments are more complex than just pro/con, but you’ve probably not been given the tools to engage with them in more complex ways.

One day (perhaps it’s a day like today!), you find yourself in college. Things might start out okay in your 1000-level courses because you might find yourself in the familiar process of examining issues or topics as two-sided. Your instructors might send you to ProCon.org, which provides students with introductions to positions for or against a specific issue. You might still be encouraged or required to write an essay following the format above: your argument(s), opposing arguments, and your rebuttals to them.

Eventually, however, in college, the assumption that arguments are binary will not work anymore. Usually by the time you are in 2000-level classes, and definitely by the time you are in 3000-level classes, your instructors are going to expect that the arguments you make will be more complex than pro/con. Even though you know, intuitively[3], that the issues you are studying in college are more than two-sided, you may not know how to think about them, how to research them, how to write about them in more complex ways. This is the college transition from binary thinking to “open-ended” thinking: responding to questions without known or certain answers. It can feel uncomfortable and confusing for students. Understanding why open-ended thinking the basis of college learning can help.

College is a place of ideas, thinking, and knowledge. Students learn content skills in college, but they also learn to critically think, to question, to theorize, to challenge, to ponder, to realize, to imagine, and to create. When we go to college, we encounter difference: different people, different values, different backgrounds, different goals, different ways of thinking. We also encounter knowledge that we do not know before we arrive in our classes.

One of the foundational qualities of a college education—regardless of your major—is that it is inquisitive. To be inquisitive[4] means to be interested in knowing, to be interested in finding out, to be interested in understanding what is unknown. This interest, this desire, is at the heart of what people do in college: research.

Everyone does research in college: professors and students alike. You may know that some college professors conduct research of their own to discover completely new knowledge, never before known by humans, like whether there is life on Mars and if humans can viably live there. Other professors might seek to confirm assumptions, like flossing teeth has positive outcomes on senior citizen health. Still others ask questions of the past, like how the North Atlantic Slave Trade impacted the economy of spice exchange. Some research methods for teaching and grading. Others work with college staff to research which types of student support can most improve graduation rates.

Notice that all of this inquiry—all of this research—is open-ended. Imagine asking about life on Mars or the potential for humans to live there in a binary format: “Should humans set up a colony on Mars?” Of course, you could respond to this in a two-sided essay with a pro/con approach:

- Introduction

- Pro Argument #1) the Earth is overheating

- Pro Argument #2) the Earth is running out of space/resources

- Con Argument #1) It’s so expensive.

a. Rebuttal #1) Saving the human race is more important than money - Conclusion

It’s a little too simple for such a complex issue, isn’t it? Maybe social media or politicians want to argue this way, but in college? We’ve got more to think about than that.

It’s not just professors who conduct research and inquiry in college. Students do as well, all the time. Knowledge doesn’t need to be brand new in order for it to be new to you; whenever you are seeking knowledge, whenever you inquire, you are living the college experience. You might want to understand the most productive ways to market a product in a world impacted by generative AI, or maybe you wonder if there are connections between climate change and refugee movement, or perhaps you have been asked to explore the issue of fentanyl abuse at high school parties. As you progress through college, the binary choices of “pro” and “con” become too limiting for all of the ideas, opinions, information, values, and thinking that surround you. Your mind and all the possibilities open to you are much bigger than that. They require open-ended thinking and conversations.

By the time you get to 2000- or 3000-level courses in college, arguments—and the research that you conduct for them—will most likely be open-ended and inquiry-based. The simplicity of “pro” and “con,” of “for” or “against,” fades away while potentially more difficult, but much more interesting, explorations of issues and questions emerge. Your assignments become more complex, and your research centers on questions that have no simple yes-or-no answer. The questions, instead, lead to open-ended conversations that you get to explore. You get to examine how knowledge and sources interact with each other in many different ways. You get to see how ideas “talk with” each other and also how you respond to them from a perspective of your own that is allowed to shift, to change, to alter, to come back to— depending on what else you discover and uncover.

Let’s go back to Chat GPT for a moment for an example of how to break away from the binary of “pro” and “con” or “claim” and “counter-claim.” Let’s ask Chat GPT the following question: “Provide me with six different opinions on regulating air pollution.” Notice that this is not a question asking whether or not we should regulate air pollution. That’s not an open-ended conversation. Yes, we probably should regulate air pollution because the option of not doing so is pretty dire, but we’re not asking that.

ChatGPT responded:

Here are six different opinions on regulating air pollution:

- Strict regulations are necessary to protect public health

- Balancing economic growth and environmental concerns

- Market-based approaches are more effective

- Voluntary measures and incentives are sufficient

- Local control and tailored regulations

- Over-regulation stifles economic growth

Each of these statements contributes a perspective to the open-ended conversation about air pollution. None of them definitively answer the question of whether we should regulate air pollution. In fact, asking ChatGPT to choose the “best” approach to regulate air pollution results in the following response:

Determining the “best” option for regulating air pollution is subjective and can vary depending on various factors such as the specific context, priorities, and values of different stakeholders. It’s important to note that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Different approaches may be more effective in different circumstances.

Open-ended conversations are not simple. They are, by their nature, complex and open. It’s this complexity that makes them much more interesting than binary thinking.

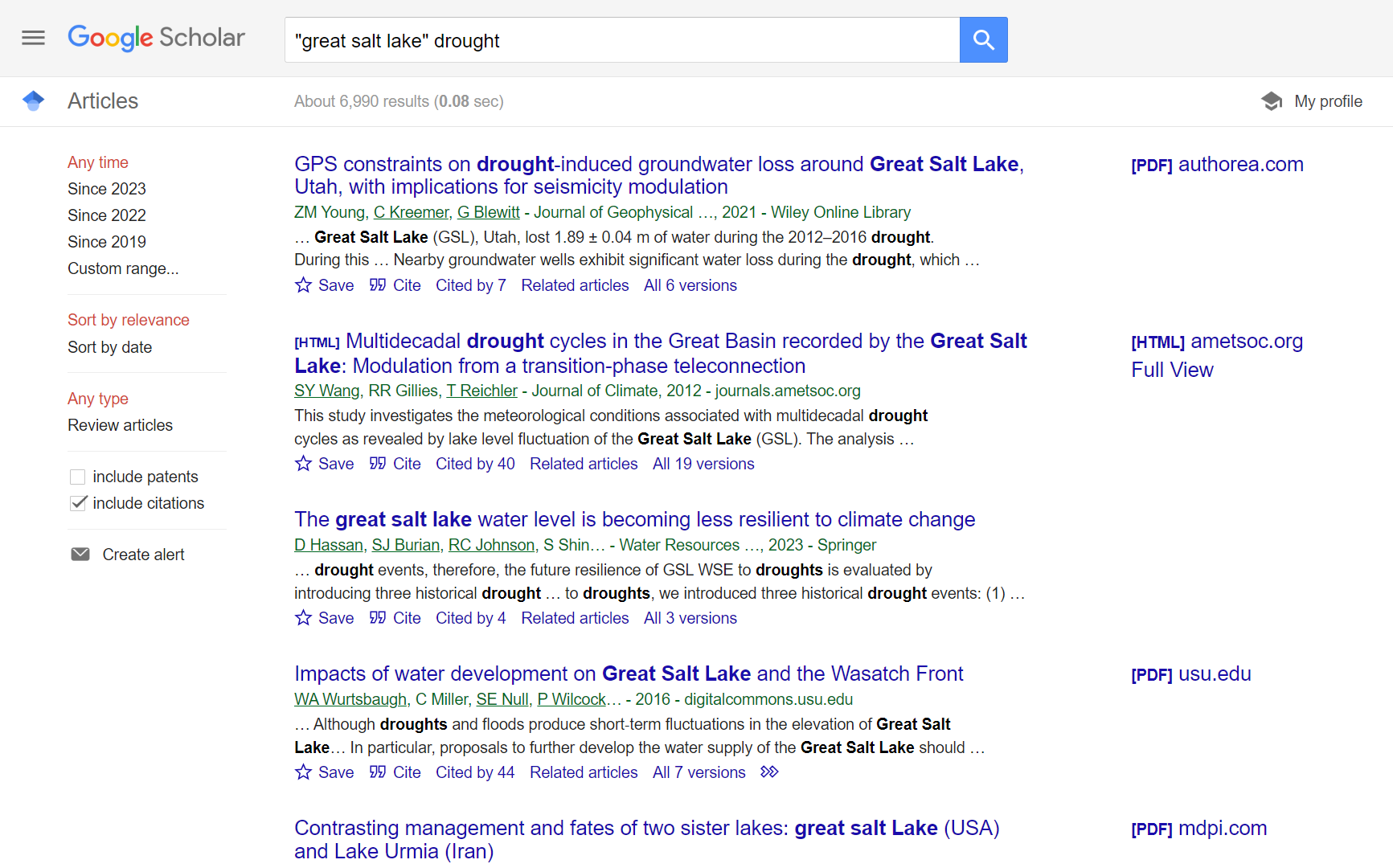

The entire job of some professors is to conduct inquiry. That’s it. Their whole purpose is to seek knowledge, to engage in researching issues as vast and wide as you can imagine (and many you can’t even imagine). These professors produce scholarship, which is reporting and sharing their research and inquiry. This scholarship—articles, books, presentations, posters, discussion posts, journals, treatises, etc.—exists within intricate networks of open-ended conversations with other researchers, students, and experts in their respective fields. A brief look at Google Scholar—a browser for academic research—provides a picture of these conversations. If we enter “great salt lake” drought into the search box, we get the following:

While you can see only five sources here, this simple search produced about 6,990 results. That’s nearly 7000 contributions to a vast open-ended conversation.

While you can see only five sources here, this simple search produced about 6,990 results. That’s nearly 7000 contributions to a vast open-ended conversation.

You can look closely at the results to see the intricate networks of conversation. First, notice the information under each entry that says, “Cited by [#].” This means that this specific resource has been cited by, or included as a resource in, other publications. These publications are actually in contact with each other. They may be providing evidence, or they could be offering alternative perspectives on the open-ended question of the Great Salt Lake drought.

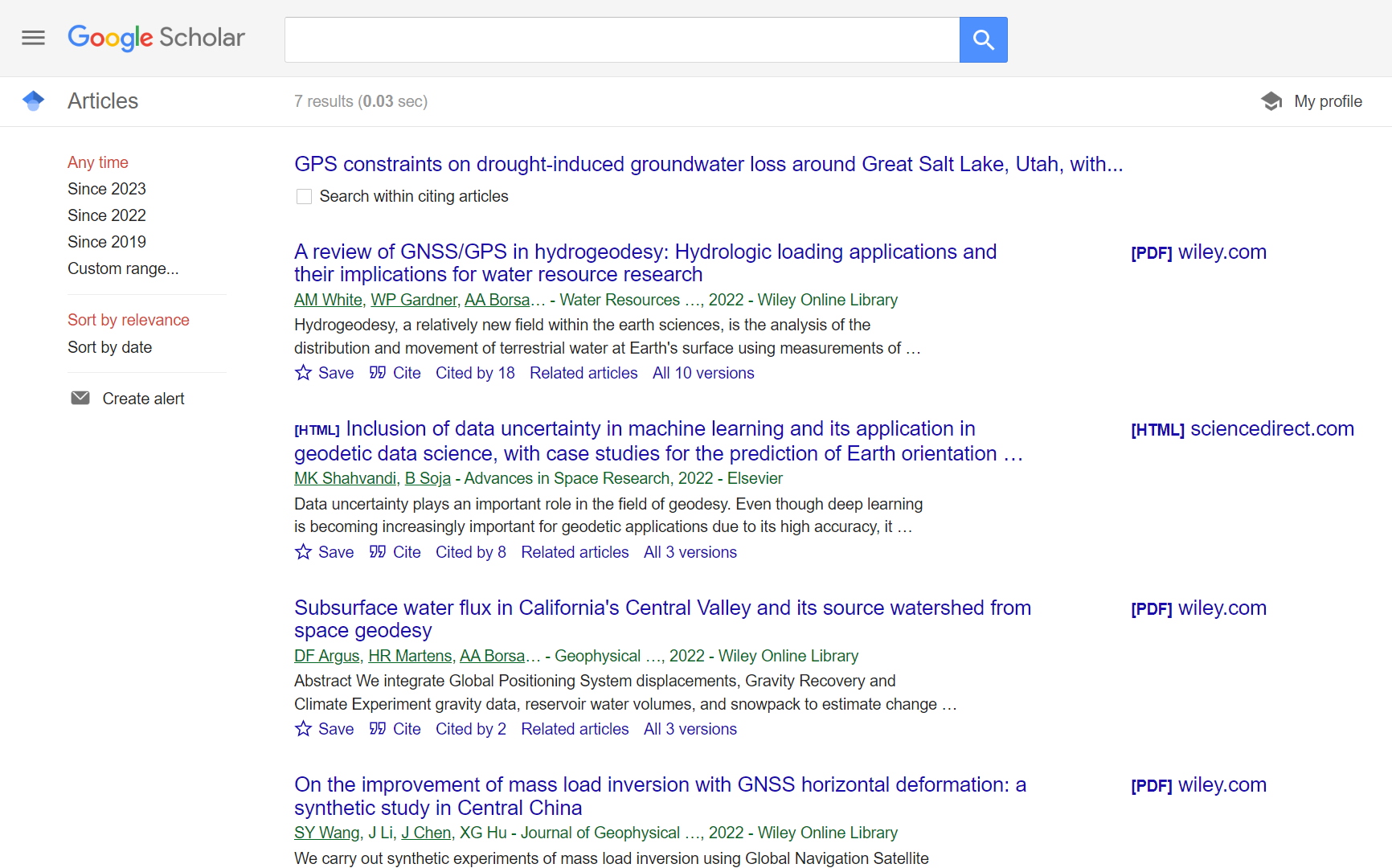

To follow the conversation beyond this initial search, let’s click on the first in the list that says it is cited by 7 other sources: “GPS constraints on drought-induced groundwater loss around Great Salt Lake, Utah, with implications for seismicity modulation.”

We are then taken to a new list of resources. We know that each of these sources has cited the above article within them. The authors of each of these articles wanted to connect their publication to the conversation going on in the previous article, likely along with dozens of others.

We are then taken to a new list of resources. We know that each of these sources has cited the above article within them. The authors of each of these articles wanted to connect their publication to the conversation going on in the previous article, likely along with dozens of others.

By skimming the titles and the abstracts, we can tell that these resources expand the conversation beyond the Great Salt Lake. At the same time, they add to the open-ended conversation about the specific drought in the Great Salt Lake by examining drought and drought-measuring methods elsewhere.

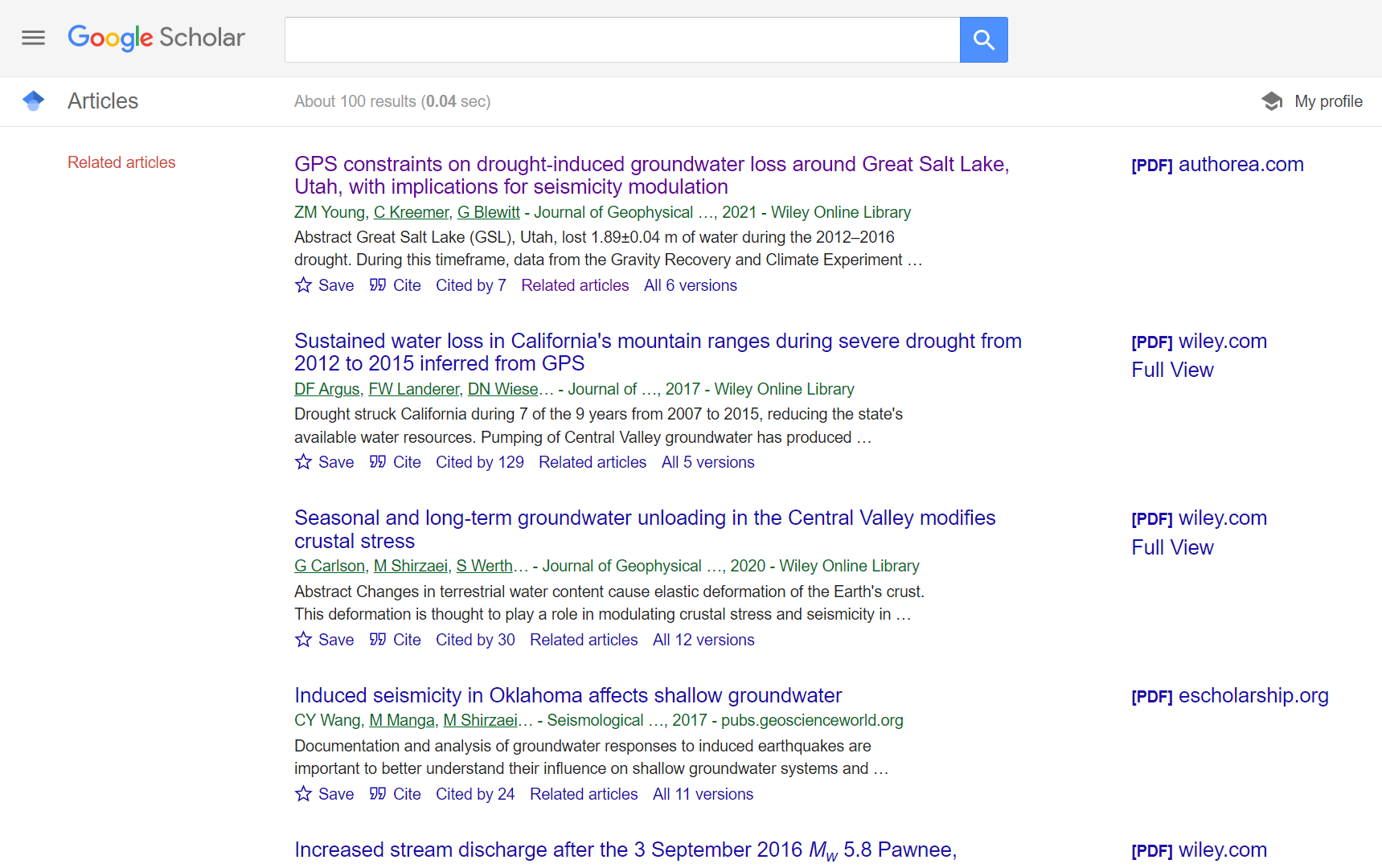

Let’s return to the original list of sources to look at another way that scholarship is involved in open-ended conversation. In addition to the “cited by” links, we also see a link under each article that says, “Related articles.” If we click again on the first article in the list, “GPS Constraints on drought-induced groundwater loss around Great Salt Lake, Utah, with implications for seismicity modulation,” we are presented with 100 articles that the Google Scholar algorithm determines are “related” in some way.

At first glance, these articles appear to be a part of the larger on-going conversation about the Great Salt Lake drought: examining water issues in other lake areas, looking at groundwater, water loss, and studying something called “crustal loading” (which could be a fascinating point of inquiry for an interested student!).

At first glance, these articles appear to be a part of the larger on-going conversation about the Great Salt Lake drought: examining water issues in other lake areas, looking at groundwater, water loss, and studying something called “crustal loading” (which could be a fascinating point of inquiry for an interested student!).

What’s important to realize is that these professors and researchers are talking to each other. It’s easy to see this conversation using Google Scholar because of the “Cited by” and “Related articles” links, but you can also see it whenever you look at the references or citations in anything that you read, watch, or listen to. Any time you see a works cited page, or a footnote linking to another source, or a hyperlink taking you to another webpage or post, you are seeing open-ended conversations in action.

Let’s get back to you and this semester. The point here is that, in college, even in ENGL 2010, you are now in a space that is much more complex than the binary thinking of “for” and “against.” This semester, you’ll be doing a significant amount of research and that research will be based in inquiry. You’ll be seeking knowledge, information, perspectives, values, findings, and more on issues that you are interested in. Within an inquiry approach to learning, you’ll be finding out what you know and don’t know, what others know and don’t know, and who gets to share their knowledge and who doesn’t.

In an inquiry approach, your research will not follow a straight line, nor will you collect all of your sources in one attempt. You’ll find a bit of knowledge and examine where it takes you, what it refers to, what it is missing. You may even end up in an entirely different place than you expected to when you started out. Your mind may change, or you may find resources that back up your initial perspectives. You just don’t know. That’s the beauty of inquiry.

This semester, and in the rest of your college career, you have the opportunity to get involved in inquiry on issues and topics that you are interested in. You get to dedicate time to thought, to ideas, to knowledge. Many, many people never get this chance, but you are here, right now, living it. Even if you are stressed out and don’t know how you are going to do it, even if you feel like you need a lot of help (which is 100% good), you are making the choice to spend time and energy and resources to be in college. That’s important. That’s a big deal. You deserve more than the oversimplification of “pro” and “con,” don’t you? You deserve open-ended conversation.

References

Columbus City Schools. “Argumentative Essay Outline (Claim).” Handout. https://www.ccsoh.us/cms/lib/OH01913306/Centricity/Domain/207/Argumentative%20Essay%20Outline.pdf Accessed May 25, 2023.

Chat GPT. Personal Communication. May 25, 2023.

Google Scholar Search. “Great Salt Lake Drought.” May 25, 2023.

- While the public presentation of argument in politics is almost always binary, the private arguments that actually lead to decisions are full of negotiation and compromise. ↵

- This example includes only the top level of the outline that Chat GPT responded with. ↵

- Intuitively: an inner sense or gut feeling rather than rational thought ↵

- intellectually curious, eager for knowledge ↵