Donald J. Trump, Pope Francis, and the Beef That Defied Space and Time

Benjamin Solomon

HERE’S AN IDEA

Language isn’t just a tool for saying things. It’s a tool people use to do things, make things, and be things in the world.

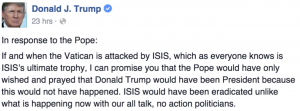

Take presidential candidate Donald Trump’s Facebook post on February 18, 2016, after Pope Francis criticized Trump’s plan to build a wall between the United States and Mexico:

As a writing teacher, I’m fascinated by these sentences. On the one hand, they’re a logical train wreck—wordy, awkward abuses of a conditional clause. On the other hand, they might also be a Jedi mind trick, carefully crafted to manipulate not just our emotions, but also the very fabric of space and time.

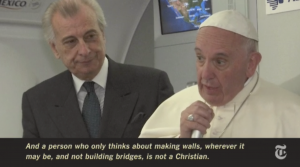

Earlier that day, a reporter aboard the papal airliner had asked Pope Francis if North American Catholics could vote for a man who wanted to build an eight-billion-dollar wall along the US–Mexican border and deport eleven million undocumented immigrants. The Pope wouldn’t say whether people should vote for Trump or not, but he did say that “a person who thinks only about building walls, wherever it may be, and not building bridges, is not a Christian.”

What’s interesting to me about this exchange is that when we take a close look at the Pope’s and Trump’s language, we can see how both were trying to do more than merely say something, or express an opinion, or just “put their thoughts out there.” Instead, they used intentional, crafted language to take specific actions, to create new meanings, and to assert their identities in the world. In other words, they used language to do things, make things, and be things.

DOING, MAKING, AND BEING

Take the Pope’s statement: “A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever it may be, and not building bridges, is not a Christian.” These words expressed serious doubt about Trump as a presidential candidate, which was bound to affect his support among American Catholic voters. That’s a significant action—one with real consequences. The Pope also clearly defined what it meant to be a Christian (a bridge-builder), versus a non-Christian (a wall-builder). By working to shape the definition of good Christian behavior, the Pope was using language to make meaning. And by choosing to speak up about political issues in the first place, the Pope was affirming his own identity as a religious leader whose views on global affairs mattered. In that sense, the Pope used language to be something in this world.

How about Trump? In his response, he shifted the focus from the Mexican border to ISIS, conflating the two. Mexico, the Vatican, and any ISIS stronghold are thousands of miles away from one another, but Trump visited all three in the span of a single sentence. However improbable, Trump’s words were language in motion—an attempt to do something. At the same time, by declaring that the Vatican was ISIS’s “ultimate trophy,” Trump also created a sense of looming danger and an impending threat that wasn’t there before. How’s that for making something with language? And since Trump was running for president at the time, with every utterance he was trying his best to be presidential. In this case, he wanted to show that he was the opposite of those “all talk, no action politicians,” and he used language to help him construct that identity.

These aren’t the only ways that the Pope and Donald Trump used language to do things, make things, and be things in the world. The closer you look at each of their motivations, audiences, word choices, methods of delivery, and yes, even their grammar, the more you’ll discover.

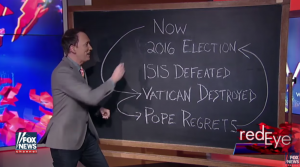

Comedian Tom Shillue used a chalkboard to break down Trump’s unlikely voyage through space and time:

Like Shillue, I’m equal parts flabbergasted and bemused by Trump’s use of language. If a student turned in a sentence like this to me, I’d comment, “I’m not sure this makes logical sense.” I’d consider it first-drafty, undercooked, and expect the writer to work on clarifying its structure and logic. So it’s tempting for me to call Donald Trump a sloppy grammarian, or a logical fallacy on legs. But actually, I think Trump’s use of language was both calculated and intentional.

JEDI MIND TRICKS

Consider Trump’s intended audience. Trump understood that his supporters—both current and potential—weren’t so much interested in elegant sentence structure and internal logic as they were in the threat of terrorism and the promise of power and safety. Trump may have been responding to the Pope, but he was actually addressing an audience of American voters who already saw immigration and terrorism as connected issues, and didn’t mind Trump defying space and time to prove it. While teleporting from Mexico to ISIS to the Vatican and back again, Trump promised a very dismal future if he wasn’t elected, or a bright, rosy, safe one if he was, and also subtly suggested that the Pope should go back to a more proper Papal activity—saying prayers—instead of meddling in politics.

The Pope, of course, did not agree. When he heard that Trump had called him “too political,” the Pope remarked, “Thank God he said I was a politician, because Aristotle defined the human person as animal politicus. At least I am a human person.” Notice how the Pope made himself sound more credible by quoting an ancient Greek philosopher, while also asserting that he’s basically just human, making him sound more humble at the same time? Nice moves, Pope Francis.

While it may come as no big epiphany to hear that public figures like Donald Trump and the Pope use language to take action, create change, and assert their identities in the world, it’s probably less appreciated that, in fact, anyone who uses language does the same thing every day. Aristotle called humans “political animals” because we’re the only ones who use words, which enable us to communicate ideas about what’s good, bad, right, and wrong. And these ideas, he said, are at the foundation of any organized group. In other words, the tool we use to build our society is language. Each of us, every day, is using language to create this world.

Next time you encounter a public beef or disagreement, pause for a moment to observe how both parties use language to do much more than just “express themselves”—how in fact, they use language as a powerful tool to take action, create meaning, and shape identity.

And keep an eye out for Jedi mind tricks. If you can recognize when someone wants you to take a flying leap through space and time in order to believe their point, you’ll be better equipped to decide if that’s really a trip you want to take.