Chapter 7: Research

This chapter is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

What is research?

What and How is Research Useful?

When conducting research, you get to ask questions and actually find answers. For example, if you have ever wondered what the best job interview strategies are, research will tell you. If you’ve ever wondered what it takes to be a NASCAR driver, an astronaut, a marine biologist, or a university professor, once again, research is one of the easiest ways to find answers to questions you’re interested in knowing. Second, research can open a world you never knew existed. We often find ideas we had never considered and learn facts we never knew when we conduct research. Lastly, research can lead you to new ideas and activities. Maybe you want to learn how to compose music, draw, learn a foreign language, or write a screenplay; research is always the best first step toward learning anything.

We define research as scholarly investigation into a topic to discover, revise, or report facts, theories, and applications. Notice that there are three distinct parts of research: discovering, revising, and reporting. The reporting function is primarily what you will be doing in this course. This is the phase when you accumulate information about a topic and report that information to others.

What is Primary and Secondary Research?

There are two main research information sources. Watch Emily Craig’s video, Market Research: the Difference Between Primary and Secondary Sources, to get a better understanding of the two.

Market Research: the Difference Between Primary and Secondary Sources, by Emily Craig, Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bPDNt9463g

1. Primary Research Sources: Primary research is reported by the person conducting the research and is considered an active form of research because the researcher is actually conducting the research for the purpose of creating new knowledge. The researcher discovers or revises facts, theories, and applications. For the purposes of your speeches, you may use two basic primary research categories: surveys and interviews. This includes firsthand research where you personally complete an interview or survey and share the results in your speech.

Conducting surveys: A survey is a collection of facts, figures, or opinions gathered from participants and used to indicate how everyone within a target group may respond. Maybe you’re going to be speaking before an education board about its plans to build a new library, so you create a survey and distribute it to all your neighbors seeking their feedback on the project. During your speech, you could then discuss your survey and the results you found.

Conducting interviews: An interview is a conversation in which the interviewer asks a series of questions aimed at learning facts, figures, or opinions from one or more respondents. As with a survey, an interviewer generally has a list of prepared questions to ask; but unlike a survey, an interview allows for follow-up questions that can aid in understanding why a respondent gave a certain answer.

2. Secondary Research Sources: Secondary research is carried out to discover or revise facts, theories, and applications and is reported by someone not involved in conducting the actual research. Most of what we consider research falls into the secondary research category. These sources are what you will mostly use for your speeches:

- Almanacs

- Atlases

- Biographical resources

- Books

- Books of quotations

- Digital collections

- Encyclopedias; Wikipedia, but only used properly

- Government publications

- Images, to an extent

- Newspapers

- Periodicals

- Podcasts

- Poetry collections

- Social news sites

- Videos

- Weblogs

- Website reference works

How do I analyze research?

Nonacademic and Academic Sources

Nonacademic sources include information sources that are sometimes also called popular press information sources; their primary purpose is to be read by the general public. Most nonacademic information sources are written at a sixth- to eighth-grade reading level, so they are very accessible. Although the information contained in these sources is often quite limited, the advantage of using nonacademic sources is that they appeal to a broad, general audience.

Nonacademic examples and resources:

Books Most college and university libraries offer both the physical stacks where the books are located and the electronic databases that contain ebooks. The two largest ebook databases are ebrary and NetLibrary. Although these library collections are generally cost-prohibitive for an individual, more and more academic institutions are subscribing to them. Some libraries are also making portions of their collections available online for free, for example, Harvard University’s Digital Collections, New York Public Library’s E-book Collection, The British Library’s Online Gallery, and the US Library of Congress. With the influx of computer technology, libraries have started to create vast stores of digitized content from around the world. These online libraries contain full-text documents, free of charge to everyone. Some online libraries we recommend are Project Gutenberg, Google Books, Open Library, and Get Free eBooks. This is a short list of just a handful of the libraries that are now offering free electronic content.

General-interest periodicals These are magazines and newsletters published on a fairly systematic basis. Some popular magazines in this category include The New Yorker, People, Reader’s Digest, Parade, Smithsonian, and The Saturday Evening Post. These magazines are considered general interest because most people in the United States find them interesting and topical.

Special-interest periodicals These are magazines and newsletters that are published for a narrower audience. In a 2005 article, Business Wire noted that in the United States there are over ten thousand different magazines published annually, but only two thousand of which have significant circulation1. More widely known special-interest periodicals are Sports Illustrated, Bloomberg’s Business Week, Gentleman’s Quarterly, Vogue, Popular Science, and House and Garden. But for every major magazine, there are a great many other lesser-known magazines, such as American Coin Op Magazine, Varmint Hunter, Shark Diver Magazine, Pet Product News International, and Water Garden News, to name just a few.

Newspapers – According to newspapers.com, the top ten newspapers in the United States are USA Today, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, the New York Daily News, the Chicago Tribune, the New York Post, Long Island Newsday, and the Houston Chronicle. Most colleges and universities subscribe to a number of these newspapers in paper form or electronic access.

Blogs – Although anyone can create a blog, there are many reputable blog sites that are run by professional journalists. As such, blogs can be a great information source. However, as with all Internet information, you must wade through much junk to find useful, accurate information. According to Technorati.com, some of the most commonly read blogs in the world in 2011 are as follows: The Huffington Post, Gizmodo, Mashable!, and The Daily Beast.

Encyclopedias – These are information sources that provide short, very general information about a topic. Encyclopedias are available in both print and electronic formats, and their content ranges from eclectic and general, such as the Encyclopædia Britannica, to the very specific, such as the Encyclopedia of 20th Century Architecture or Encyclopedia of Afterlife Beliefs and Phenomena. One of the most popular online encyclopedic sources is Wikipedia. Like other encyclopedias, Wikipedia can be useful for finding basic information, such as the baseball teams that Catfish Hunter played for, but will not give you the depth of information you need for a speech. Also, keep in mind that Wikipedia can be edited by anyone, unlike the general and specialized encyclopedias available through your library, and therefore, often contains content errors and biased information

Websites – These are the last major nonacademic information sources. In the twenty-first century, we live in a world where there is much information readily available at our fingertips. Unfortunately, you can spend hours and hours searching for information and never quite find what you’re looking for if you don’t devise an Internet search strategy. First, select a good search engine to help you find appropriate information. This list contains links to common search engines and the general information found there

Search Engines

US Government Sites

Medical Sites

Comparison Shopping

US Population Statistics

Art-related Information

Academic and Scholarly Sources These include texts that are read by dozens of academics who provide feedback. If you include academic research in your writing process, it will be time consuming, but it provides you with an extra level of confidence in the information’s relevance and accuracy. The main difference between academic or scholarly information and the information you get from the popular press is oversight. In the nonacademic world, the primary information gatekeeper is the editor, who may or may not be a content expert. Academia has established a way to perform a series of checks to ensure that the information is accurate and follows agreed-upon academic standards. In this section, we will discuss scholarly books and articles, computerized databases, and scholarly web information.

Academic examples and resources:

Scholarly Books – According to the Text and Academic Authors Association, there are two types of scholarly books: textbooks and academic books. Textbooks are books that are written about a segment of content within an academic field and are written for undergraduate or graduate student audiences. These books tend to be very specifically focused. Academic books are books that are primarily written for other academics for informational and research purposes. Generally speaking, when instructors ask you to find scholarly books, they are referring to academic books. Thankfully, there are hundreds of thousands of academic books published on almost every topic you can imagine. In the communication, field, there are a handful of major publishers who publish academic books, for example, SAGE, Routledge, Jossey-Bass, Pfeiffer, the American Psychological Association, and the National Communication Association, among others.

Scholarly Articles – Because most academic writing comes in the form of scholarly articles or journal articles, these are the best places to find academic research on a given topic. Every academic subfield has its own journals, so you should never have a problem finding the best and most recent topic research. However, scholarly articles are written for a scholarly audience, so reading scholarly articles takes more time than if you were to read a popular press-magazine article. It’s also helpful to realize that there may be parts of the article you simply do not have the background knowledge to understand, and there is nothing wrong with that. Many research studies are conducted by quantitative researchers who rely on statistics to examine phenomena. Unless you have training in understanding the statistics, it is difficult to interpret the statistical information that appears in these articles. Instead, focus on the beginning part of the article where the authors discuss previous secondary research, and then focus at the article’s end, where the authors explain what was found in their primary research.

Computerized Databases – Finding academic research is easier today than it ever has been because of large computer databases. Here’s how these databases work: a database company signs contracts with publishers to gain the right to store the publishers’ content electronically. The database companies then create thematic databases containing publications related to general knowledge areas, such as business, communication, psychology, medicine, etc. The database companies then sell database subscriptions to libraries. Use our SLCC library database.

How to Use SLCC Library

The Web – In addition to the subscription databases, there are also numerous great sources for scholarly information on the web. As mentioned earlier, however, finding scholarly information on the web poses a problem because anyone can post information on the web. Fortunately, there are many great websites that filter this information for us.

Scholarly Information on the Web

| Website | Type of Information |

|---|---|

| The Directory of Open Access Journals | The Directory of Open Access Journals is a free, online academic journals database. |

| Google Scholar | Google Scholar attempts to filter out nonacademic information. Unfortunately, it tends to return a large number of for-pay site results. |

| Communication Institute for Online Scholarship | Communication Institute for Online Scholarship is a clearinghouse for online communication scholarship. This site contains full-text journals and books. |

| Los Alamos National Laboratory | This is an open-access site devoted to making physical science research accessible. |

| BioMed Central | BioMed Central provides open-access medical research. |

| OSTI.gov | OSTI.gov provides access to scholarly research that interests people working for the Department of Energy. |

| Free Medical Journals | This site provides the public with free access to medical journals. |

| Highwire Stanford | This is the link to Stanford University’s free, full-text science archives. |

| Public Library of Science | This is the Public Library of Science’s journal for biology. |

Tips for Finding Authoritative and Credible Sources and Evidence

- Create a Research Log – George believes it’s important to keep a “step-by-step account of the process of identifying, obtaining, and evaluating sources for a specific project…” (George, 2008). In essence, keeping a log of your research is very helpful because it can help you keep track of what you’ve read thus far.

- Start with Background Information – It’s not unusual for students to try to jump right into the meat of a topic, only to find out that there is a lot of technical language they just don’t understand. For this reason, start your research with sources written for the general public. Generally, these lower-level sources are great for topic background information and are helpful when trying to learn a subject’s basic vocabulary.

- Search your Library – Try to search as many different databases as possible. Look for relevant books, ebooks, newspaper articles, magazine articles, journal articles, and media files. Modern college and university libraries have a ton of sources, and one search may not reveal everything you are looking for on the first pass. Furthermore, don’t forget to think about topic synonyms. The more topic synonyms you can generate, the better you’ll be at finding information.

- Learn to Skim – Start by reading the introductory paragraphs. Generally, the first few paragraphs will give you a good idea about the overall topic. If you’re reading a research article, start by reading the abstract. If the first few paragraphs or abstract don’t sound like they’re applicable, there’s a good chance the source won’t be useful for you. Second, look for highlighted, italicized, or bulleted information. Generally, authors use highlighting, italics, and bullets to separate information to make it jump out for readers. Third, look for tables, charts, graphs, and figures. All these forms are separated from the text to make the information more easily understandable for a reader, so discovering if the content is relevant is a way to see if it helps you. Fourth, look at headings and subheadings. Headings and subheadings show you how an author has grouped information into meaningful segments.

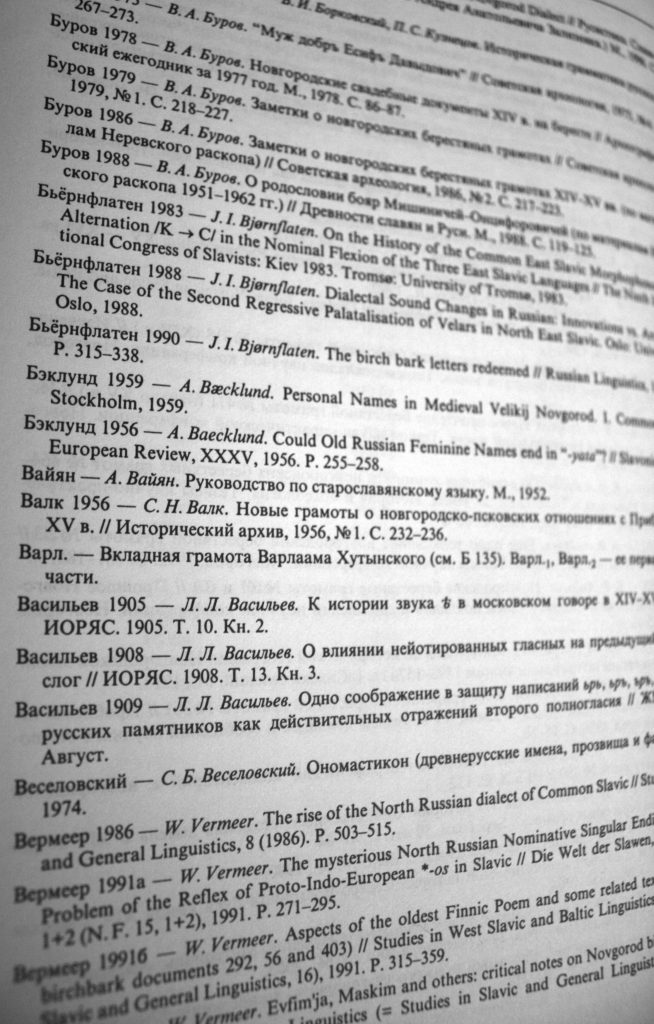

- Read Bibliographies and Reference Pages – After you’ve finished reading useful sources, see who those sources cited on their bibliographies or reference pages. We call this method backtracking. Often, the sources cited by others can lead us to even better sources than the ones we found initially.

- Ask for Help – Don’t be afraid to ask for help. Librarians are your friends. They won’t do your work for you, but they are more than willing to help if you ask.

How to Analyze Sources

To analyze your sources, follow these guidelines:

Consider the Source

- The source is the author and or publisher who provides the information you are reading.

- Is it clear who the source is? If not, be suspicious of that website or article.

- Is the source qualified? Does the author have the qualifications to speak on the subject? If there is no author or there is no information about the author, be suspicious. Use profnet to search for credible source information.

- Are there references attached to the website or article you are looking at? Are those references verifiable and credible? If you look at a source’s bibliography or reference page, and it has only a couple of citations, then you can assume that either the information was not properly cited, or it was largely made up by someone.

- Are other people actively citing the work? One way to find out whether a given source is widely accepted is to see if numerous people are citing it. If you find an article that has been cited by many other authors, then clearly the work has been viewed as credible and useful.

- Academic or not? Because of the enhanced scrutiny academic sources go through, we argue that you can generally rely more on the information contained in academic sources than nonacademic sources.

Consider Source Bias

- Take a look at this article.

- This article gives a list of websites that might not pass some of our consider-your-source bias. Take a look and see which of these websites are biased.

- Even though a source may have credible information, if it clearly has a vested interest in something, look elsewhere.

Determine Document Currency

- How long has it been since the website has been updated? When was the article written? If the answer is 2012 or earlier, find something more recent since information may have changed in the last five years.

- Ensuring your evidence is recent is important to your speaker credibility.

- Not all information that is old however, is irrelevant. Sometimes, we must look at history to understand the present or to predict the future. Some facts and information have not changed much or at all over time.

Use Fact-Checking Sites

- This site-list can be used to fact check information you are not sure is accurate in an article or website. If you find inaccurate information, look for a more credible information source.

- Pop Culture and Urban Myths: Snopes

- Politcal Claims: PolitiFact, Factcheck, The Fact Checker

- Medical Claims: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Health Central

- News Events: Check reputable news organizations such as the New York Times, BBC News, or CNN

How do I cite my sources in a speech?

Citation Style

Citation styles provide particular formats for in-text citations and bibliographies to use in your research paper. Choose the citation style based on the discipline in which you are writing. Usually, your professor will indicate the citation style that he or she would like you to use (guides.temple.edu). Some common citation styles:

- American Psychological Association, APA Style: frequently used in the social sciences.

- Chicago Manual of Style, Chicago Style: Notes and Bibliography format is often used in the humanities; Author-Date format is often used in the social sciences and sciences.

- Modern Language Association, MLA Style: widely used in the humanities (guides.temple.edu).

The APA and the MLA are two commonly used style guides in academia today. Generally speaking, scholars in the various social science fields, such as psychology, human communication, and business are more likely to use APA style, and scholars in the various humanities fields such as English, philosophy, and rhetoric are more likely to use MLA style, in addition to Chicago Manual for publishing. These styles are quite different from each other, so learning them takes time.

APA Style

In this course, you will use APA style in your written work and your speech citations. First, let’s discuss how to cite research references inside your written work and at the end for your bibliography and works-cited page.

How to cite research references inside your outline

When citing research references inside your outline, they are called in-text or parenthetical citations. Look at EasyBib’s website, which has a list of different examples to help you see how it is done in APA format.

As you probably noticed, in-text or parenthetical citations are very similar to the way you might cite your research references inside an English or research paper. Since the outlines for your speeches are full sentences, use the same in-text citation. Look at SLCC Libguides for another example of in-text citations.

How to cite research reference pages at the end of your outline

The reference page, also known as a bibliography or works-cited page, is the last page on your outline. How you title this page depends on if you are using APA, MLA, or Chicago Style, etc. In APA format, which is what we will use in this class, use the title, “References.” Visit the Purdue Owl website and navigate to the bottom of the page to see an example. The Purdue Online Writing Lab is also a great site to help you with APA format for your speech research.

There are several places you can go online and in Microsoft Word that will cite sources for you in APA. These are called citation managers, which are software programs used to download, organize, and output your citations. You can output thousands of different citation styles, including APA, Chicago, and MLA using citation managers (guides.temple.edu). All you have to do is input the information! When you use the SLCC library to do research, they provide automatic APA citation for you!

Citation Machine

Scribbr

The Owl at Purdue

Citing Sources Orally in a Speech

Now, we will discuss how to use oral citations in your speech and provide examples. This will be extremely important to your class grade, as you will be graded on the way you cite your sources orally in your speech and how many citations you mention. Keep in mind that written references are more complete and more formal than oral references, which means you want your oral citations in your speech to flow and fit in with the rest of your speech’s content.

Either immediately before or after you give source information during your speech, identify these key oral citation standards or elements:

- Name the website, author, person, magazine, etc.

- State your source’s credentials—ethos. This includes the person, website, etc. and explain in your speech why and how this is an authoritative topic source. Explain why you are using this source compared to other possible sources.

- Give the article, book, or video title, etc.

- Give the source’s date, if it is necessary and relevant, which it usually is.

Here are some examples that correspond to the numbers above:

“According to Dr. Jim Pritchard, a practicing architect in Salt Lake City, architecture is not a dying discipline but is actually thriving ….” (2)

“The 2016 edition of Crompton’s Encyclopedia explains that … “(3, 4)

“I read in my English textbook, Effective Writing, that writing skills are one of the number-one skills required to have a successful career …. “(3)

Example from your textbook in Appendix A: “It killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide and 675,000 Americans, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Website flu.gov.” (1, 3)

According to Melanie Smithfield in an article titled “Do It Right, or Do It Now,” published in the June 18, 2009, issue of Time Magazine… (1, 2, 3, 4)

According to Roland Smith, a legendary civil rights activist and former chair of the Civil Rights Defense League, in his 2001 book The Path of Peace… (1, 2, 3, 4)

Here is an example of an informative speech given during a competition. Listen carefully for the sources, and watch how the speaker seamlessly gives his audience evidence.

Robert Cannon NFA Info Finals – Informative Speaking, by Cannonball of Death, Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SogNbDakslQ

Key things to remember:

- Is it important that you explain who the author of a text is? Or, why is the source website relevant to your speech’s topic? Why mention the research study date or a source-book title? By including this explanation in your speech you help the audience see the ethos or credibility in your sources, and therefore, your credibility as the speaker.

- Mentioning your sources boosts your credibility. If you are not a credible speaker, people won’t take you seriously; they won’t listen to you at all; or they could even make you look bad in public, embarrass you, or ruin your reputation, etc.

- Proper oral speech citation also helps you avoid oral plagiarism, which is a serious issue and could lead to failing the class or being kicked out of school, etc. Oral plagiarism has the same consequences as written plagiarism.

What does it mean to use sources ethically?

Avoid Plagiarism

If the idea isn’t yours, cite the information source during your speech. Listing the citation on a bibliography or reference page is only half of the correct citation. You must provide correct citations for all your sources within your speech as well. In a very helpful book called Avoiding Plagiarism: A Student Guide to Writing Your Own Work, Menager-Beeley and Paulos provide a list of twelve strategies for avoiding plagiarism (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009):

- Do your own work, and use your own words. One of the goals of a public speaking class is to develop skills that you’ll use in the world outside academia. When you are in the workplace and the real world, you’ll be expected to think for yourself, so start learning this skill now.

- Allow yourself enough time to research the assignment. Not having adequate time to prepare is no excuse for plagiarism.

- Keep careful track of your sources. A common mistake people make is that they forget where information came from when they start creating the speech itself. When you log your sources, you’re less likely to inadvertently lose sources and to cite them incorrectly.

- Take careful notes. It doesn’t matter what method you choose for taking research notes, but whatever you do, be systematic to avoid plagiarizing.

- Assemble your thoughts, and make it clear who is speaking. When creating your speech, make sure that you clearly differentiate your voice in the speech from your quoted author’s voice. The easiest way to do this is to create a direct quotation or a paraphrase. Remember, audience members cannot see where the quotation marks are located within your speech text, so clearly articulate with words and vocal tone when you are using someone else’s ideas within your speech.

- If you use an idea, a quotation, paraphrase, or summary, then credit the source. We can’t reiterate it enough—if it is not your idea, tell your audience where the information came from. Giving credit is especially important when your speech includes a statistic, an original theory, or a fact that is not common knowledge.

- Learn how to cite sources correctly, both in the body of your paper and in your reference or works-cited page.

- Quote accurately and sparingly. A public speech should be based on factual information and references, but it shouldn’t be a string of direct quotations strung together. Experts recommend that no more than 10 percent of a paper or speech be direct quotations (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009). When selecting direct quotations, always ask yourself if the material could be paraphrased in a manner that would make it clearer for your audience. If the author wrote a sentence in a way that is just perfect, and you don’t want to tamper with it, then by all means directly quote the sentence. But if you’re just quoting because it’s easier than putting the ideas into your own words, this is not a legitimate reason for including direct quotations.

- Paraphrase carefully. Modifying an author’s words is not simply a matter of replacing some of the words with synonyms. Instead, as Howard and Taggart explain in Research Matters, “paraphrasing force[s] you to understand your sources and to capture their meaning accurately in original words and sentences” (Howard & Taggart, 2010). Incorrect paraphrasing is one of the most common ways that students inadvertently plagiarize. First and foremost, paraphrasing is putting the author’s argument, intent, or ideas into your own words.

- Do not patchwrite or patchspeak. Menager-Beeley and Paulos define patchwriting as “mixing several references together and arranging paraphrases and quotations to constitute much of the paper. In essence, the student has assembled others’ work with a bit of embroidery here and there but with little original thinking or expression” (Menager-Beeley & Paulos, 2009). Just as students can patchwrite, they can also patchspeak. In patchspeaking, students rely completely on weaving together quotations and paraphrases in a manner that is devoid of the student’s original thinking.

- Do not auto-summarize. Some students have learned that most word processing features have an auto-summary function. The auto-summary function will summarize a ten-page document into a short paragraph.

- Do not rework another student’s speech or buy paper-mill papers or speech-mill speeches. In today’s Internet environment, there are numerous student-speech storehouses on the Internet. Whether you use a speech that is freely available or pay money for a speech, you are plagiarizing. This is also true if your speech’s main substance was copied from a web page. Any time you try to present someone else’s ideas as your own during a speech, you are plagiarizing.

Use Sources Ethically In a speech

Ways to use sources ethically in a speech:

- Avoid plagiarism, as we already discussed.

- Avoid Academic Fraud – While there are numerous websites from which you can download free speeches for your class, this is tantamount to fraud. If you didn’t do the research and write your own speech, then you are fraudulently trying to pass off someone else’s work as your own. In addition to being unethical, many institutions have student codes that forbid such activity. Penalties for academic fraud can be as severe as suspension or expulsion from your institution.

- Don’t Mislead Your Audience – If you know a source is clearly biased, and you don’t spell this out for your audience, then you are purposefully trying to mislead or manipulate your audience. Instead, if you believe the information to be biased, tell your audience and allow them to decide whether to accept or disregard the information.

- Give Author Credentials – Always provide the author’s credentials. In a world where anyone can say anything and have it published on the Internet or even in a book, we have to be skeptical of the information we see and hear. For this reason, it’s very important to provide your audience with background information about your cited authors’ credentials.

- Use Primary Research Ethically – Lastly, if you are using primary research within your speech, you need to use it ethically as well. For example, if you tell your survey participants that the research is anonymous or confidential, then make sure that you maintain their anonymity or confidentiality when you present those results. Furthermore, be respectful if someone says something is off the record during an interview. Always maintain participants’ privacy and confidentiality during primary research unless you have their express permission to reveal their names or other identifying information.

How do I establish ethos?

Establishing ethos—one of the three rhetorical appeals—is achieved by including authoritative evidence or research inside of your speech. You establish ethos as well through your credibility and ethics as a speaker.

Here are some questions to ask yourself as you prepare to establish ethos for any speech:

Credibility

- Does the audience see you as topic-credible? What have you done or said to ensure this?

- What makes you credible? Do you explain your credibility to the audience in the speech?

- Can the audience trust you? What reason have you given them to trust you?

Authoritative Sources

- Do you cite your authoritative sources out loud in your speech?

- Are your sources actually authoritative for this topic?

- What makes your sources authoritative? Do you explain that to your audience?

Appearance

- Does your dress, clothing, and appearance match the topic, occasion, and audience for your speech? How might your audience perceive your appearance from your perspective?

You must be able to answer all of these questions with a yes and a good explanation. The audience should clearly hear and see your ethos in your speech.

References

University of Minnesota. (2016). Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Media References

Cannonball of Death. (2011, January 3). Robert Cannon NFA Info Finals – Informative Speaking [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SogNbDakslQ

Craig, E. (2019, September 20). Market Research: the Difference Between Primary and Secondary Sources [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bPDNt9463g

Dombrowski, Q. (2010, October 28). Bibliography [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/quinnanya/5124103273/

Fuller, A. (2022, May 5). Textbook Cartoon [Image]. Center for eLearning, Salt Lake Community College.

Geralt. (2021, May 20). Arrows Direction Way [Image]. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/illustrations/arrows-direction-way-sketch-false-6268063/

Not of or relating to formal study.

A long written or printed literary composition.