Chapter 4: Getting the Audience to Listen

This chapter is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

How do I effectively imbed stories in a speech?

Once you have learned to tell a story well, you can imbed them in your speeches. Using stories along with your research and data are a powerful combination to inform and persuade audiences.

You may think you won’t have enough time to share a story when you present your speech in this class. However, a story can often be told in a sentence or two.

In this speech by funny Harvard professor Shawn Achor, you may be surprised by how many stories he packs into his twelve-minute Ted Talk, The Happy Secret to Better Work. He also includes data and research. Near the speech’s end, don’t miss how Achor shares five surprising ways to improve your speech skills.

Shawn Achor: The happy secret to better work, by TED, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Isn’t it interesting to hear how happiness creates success? Did you identify any of the five practices Achor indicated will improve happiness, which then improves success? If you missed them, you can always watch the video again. Also, you can use these strategies to reduce anxiety.

Can you guess how many stories Achor told? The answer is below the following bullets.

Remember, you are also a people watcher.

- Did you notice how different Achor’s storytelling style is from Donald Davis’ storytelling style?

- Did you notice if Achor also used the four Ps?

- What did you like about Achor’s storytelling?

- What would you suggest Achor do to improve? Did you notice how fast he talked?

Shawn Achor told ten stories in twelve minutes.

How do I get my audience to listen?

How do you get your audience to listen? This question is key in preparing to give any speech and requires that, as speakers, we are good listeners as well. Here is how it works.

“Are you listening to me?” This question is often asked because the speaker thinks the listener is nodding off or daydreaming. We sometimes think that listening means we sit back, stay barely awake, and let a speaker’s words wash over us. While many Americans look upon being active as something to admire, to engage in, and to excel at, listening is often understood as a passive activity. More recently, the O, the Oprah Magazine featured a cover article with the title, “How to Talk So People Really Listen: Four Ways to Make Yourself Heard.” This title leads us to expect a list of ways to make people listen, but the article contains a surprise ending. The final piece of advice is this: “You can’t go wrong by showing an interest in what other people say and by making them feel important. In other words, the better you listen, the more you’ll be listened to” (Jarvis, 2009).

You may have heard the adage, “We have two ears but only one mouth”—an easy way to remember that listening can be twice as important as talking. As a student, you are most likely to spend many hours in a classroom doing much focused listening, yet sometimes it is difficult to apply those efforts to communication in other areas of your life. As a result, your listening skills may not be all they could be. In this chapter, we will examine listening versus hearing, listening styles, listening difficulties, listening stages, and listening critically.

What is the difference between listening and hearing?

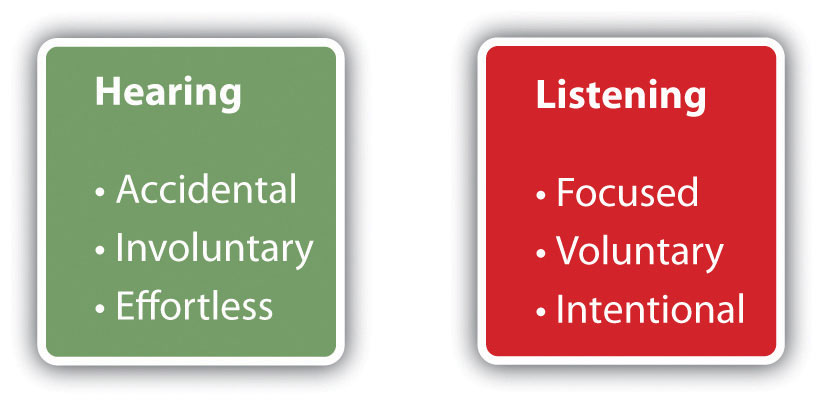

Listening or Hearing

Hearing is an accidental and automatic brain response to sound that requires no effort. We are surrounded by sounds most of the time. For example, we are accustomed to the sounds of airplanes, lawn mowers, furnace blowers, the rattling of pots and pans, and so on. We hear those incidental sounds, and unless we have a reason to do otherwise, we train ourselves to ignore them. We learn to filter out sounds that mean little to us, just as we choose to hear our ringing cell phones and other sounds that are more important to us.

Listening, on the other hand, is purposeful and focused rather than accidental. As a result, it requires motivation and effort. Listening, at its best, is active, focused, concentrated attention for the purpose of understanding a speaker’s expressed meaning. We do not always listen at our best, however. Later in this chapter, we will examine some of the reasons why and provide some strategies for becoming more active critical listeners.

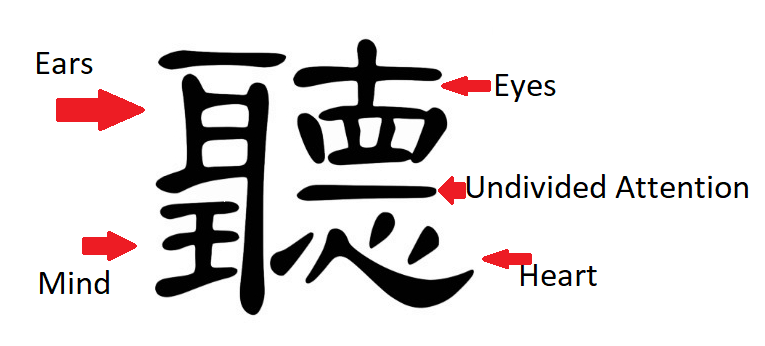

The Chinese character for listen illustrates just how much of ourselves involves listening well. The cross over the symbol for “eyes” is the number ten. Consider why it takes ten eyes to listen.

Benefits of Listening

Listening should not be taken for granted. Before writing was invented, people conveyed virtually all knowledge through some combination of showing and telling. Elders recited tribal histories to attentive audiences. Listeners received religious teachings enthusiastically. Entertaining myths, legends, folktales, and stories survived because audiences were eager to listen. Today, however, we are informed and entertained by reading, watching, and listening to electronic recordings rather than through real-time listening. If you become distracted and let your attention wander, you can go back and replay a recording. So why learn listening skills? Here are four compelling benefits to becoming a more active and competent real-time listener.

You Become a Better Student

When you focus on the material presented in a classroom, you will be able to identify not only the words used in a lecture but their emphasis and their more complex meanings. You will take better notes, and you will more accurately remember the instructor’s claims, information, and conclusions. Many times, instructors give verbal cues about what information is important, specific expectations about assignments, and even what material is likely to be on an exam, so careful listening can be beneficial.

You Become a Better Friend

When you give your best attention to people expressing thoughts and experiences that are important to them, those individuals are likely to see you as someone who cares about their well-being. This fact is especially true when you give only your attention and refrain from interjecting opinions, judgments, and advice.

People Will Perceive You as Intelligent and Perceptive

When you listen well to others, you reveal yourself as being curious and interested in people and events. In addition, your ability to understand the meaning of what you hear will make you a more knowledgeable and thoughtful person.

Good Listening Can Help Your Public Speaking

When you listen well to others, you can pick up on the stylistic components related to how people form arguments and present information. As a result, you have the ability to analyze what you think works and doesn’t work in others’ speeches, which can help you transform your speeches in the process. For example, really paying attention to how others cite sources orally during their speeches may give you ideas about how to more effectively cite sources in your presentation.

What are the different listening styles?

You and your audience will have various listening styles. Creating a speech that appeals to each listening style will help you keep your audience’s attention.

If listening were easy and if all people went about it in the same way, a public speaker’s task would be much easier. Even as long ago as 325 BC, Aristotle recognized that his listeners had varied listening styles.

Aristotle classified his listeners into three categories: those who would make decisions about past events, those who would make decisions affecting the future, and those who would evaluate the speaker’s skills. This is all the more remarkable when we consider that Aristotle’s audiences were exclusively all prosperous property-owning males from one city-state.

Our audiences today are likely to be much more heterogeneous. During this course, think about your audience: your classmates come from many religious and ethnic backgrounds. Some may speak English as a second language. Some might be survivors of war-torn parts of the world such as Bosnia, Darfur, or northwest China. Being mindful of such differences will help you prepare a speech in which you minimize the potential for misunderstanding.

Part of the potential for misunderstanding is the difference in listening styles. In the International Journal of Listening, Watson, Barker, and Weaver (Watson, et al., 1995) identified four listening styles: people, action, content, and time.

People

People-oriented listeners are interested in the speaker. People-oriented listeners listen to the message to learn how the speaker thinks and how they feel about their message. For instance, when people-oriented listeners listen to a famous rap artist’s interview, they are likely to be more curious about the artist as an individual than about music, even though the people-oriented listener might also appreciate the artist’s work. If you are a people-oriented listener, you might have certain questions you hope will be answered, such as:

- Does the artist feel successful?

- What’s it like to be famous?

- What kind of educational background does the artist have?

In the same way, if we’re listening to a doctor who responded to an earthquake crisis in Haiti, we might be more interested in the doctor as a person than in the Haitians’ state of affairs. You might have certain questions you hope will be answered, such as:

- Why did the doctor go to Haiti?

- How did the doctor get time away from a normal practice and patients?

- How many lives did the doctor save?

As people-oriented listeners, we might be less interested in the equally important and urgent needs for food, shelter, and sanitation following the earthquake.

The people-oriented listener is likely to be more attentive to the speaker than to the message. If you tend to be such a listener, understand that the message is about what is important to the speaker.

Action

Action-oriented listeners are primarily interested in finding out what the speaker wants. Does the speaker want votes, donations, volunteers, or something else? It’s sometimes difficult for an action-oriented listener to give their full attention through the descriptions, evidence, and explanations with which a speaker builds his or her case.

Action-oriented listening is sometimes called task-oriented listening. In it, the listener seeks a clear message about what needs to be done and might have less patience for listening to the reasons behind the task. This can be especially true if the reasons are complicated. For example, when you’re a passenger on an airplane, a flight attendant delivers a brief speech called the preflight safety briefing. The flight attendant does not read a seat-belt safety study or regulations findings. The flight attendant doesn’t explain that the speech’s content is actually mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration. Instead, the attendant says only to buckle up so the plane can leave the gate. An action-oriented listener finds “buckling up” a more compelling message than a message about the underlying reasons.

Content

Content-oriented listeners are interested in the message itself, what it means, whether it makes sense, and whether it’s accurate. When you give a speech, many classroom audience members will be content-oriented listeners who will be interested in learning from you. Therefore, you have an obligation to represent the truth in the fullest way you can. You can emphasize an idea, but if you exaggerate, you could lose credibility in the minds of your content-oriented audience. You can advocate ideas that are important to you, but if you omit important limitations, you are withholding part of the truth and could leave your audience with an inaccurate view.

Imagine you’re delivering a speech on the plight of African orphans. If you just talk about the fact that there are over forty-five million orphans in Africa but don’t explain why, you’ll sound like an infomercial. In such an instance, your audience’s response is likely to be less enthusiastic than you might want. Instead, content-oriented listeners want to listen to well-developed information with solid explanations.

Time

Time-oriented listeners prefer a message that gets to the point quickly. Time-oriented listeners become impatient with slow deliveries or lengthy explanations. This listener may be receptive for only a short time and may become rude or even hostile if the speaker expects them to focus their attention for long. Time-oriented listeners convey their impatience through eye rolling, shifting about in their seats, checking their cell phones, and other inappropriate behaviors. For example, if you’ve been asked to speak to middle-school students, be aware that their attention spans are simply not as long as college students. This is an important reason why speeches given to young audiences must be shorter or broken up by more variety than speeches given to adults.

In your professional future, some of your audience members will have real time constraints, not merely perceived ones. Imagine that you’ve been asked to deliver a speech on a new project to a local corporation’s board of directors. Chances are, the board members are all pressed for time. If your speech is long and filled with overly detailed information, time-oriented listeners will simply start to tune you out as you’re speaking. Obviously, if time-oriented listeners start tuning you out, they will not be listening to your message. This type of time-oriented listener may indeed be interested in the message, but truly does not have the time.

Interesting Fact

Most people speak at a rate of 125 words per minute, but we listen at a rate between 500–800 words per minute! Because of this gap, we lose concentration, and our mind wanders when we try to listen to others.

There are also three other elements that influence listening styles.

Auditory listeners learn best when they hear the information. This seems like the easiest element for a speaker to accommodate because we speak our information. However, speaking with effective vocal variety is the key.

Tactile listeners learn best when they can touch or experience the information. This may be the most difficult element because we don’t often find a way for audiences to participate experientially. However, it can be done. A person speaking on relaxation techniques can invite the audience to do a breathing exercise. A person speaking about how friction works can ask the audience to rub their hands together briskly to feel how quickly friction warms their hands.

Visual listeners learn best when they can see the information. This learner enjoys visual aids, posters, PowerPoints, or models of the speech’s concepts to help digest the information.

Why is listening difficult?

At times, everyone has difficulty staying completely focused during a lengthy presentation. Sometimes, we have difficulty listening to even relatively brief messages. Some factors that interfere with good listening might exist beyond our control, but others are manageable. It’s helpful to be aware of these factors so that they interfere as little as possible with understanding the message.

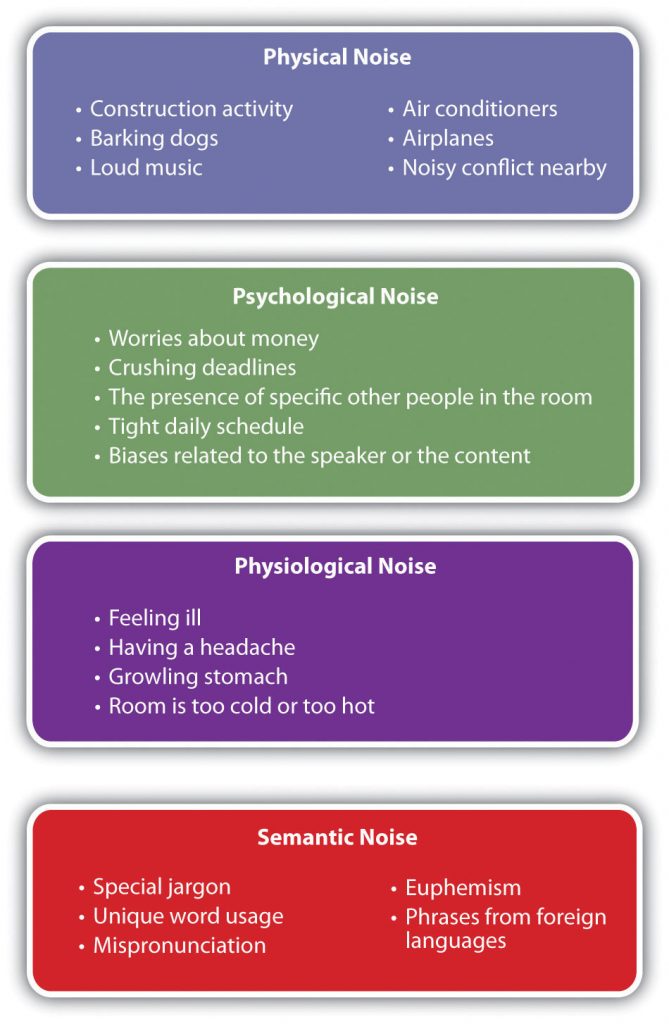

Noise

Noise is one of the biggest factors that interferes with listening; it can be defined as anything that interferes with your ability to attend to and understand a message. There are many kinds of noise, but we will focus on only the four you are most likely to encounter in public speaking situations: physical psychological, physiological, and semantic.

Physical Noise

Physical noise consists of various environmental sounds that interfere with an audience’s ability to hear. Construction noise right outside a window, planes flying directly overhead, or loud music in the next room can make it difficult to hear a speaker’s message even when he or she is using a microphone. It is sometimes possible to manage or reduce the noise. For example, closing a window or asking the people in the next room to possibly turn down their music might help. Changing to a new location is more difficult, as it involves finding a new location and getting everyone there.

Psychological Noise

Psychological noise consists of a listener’s own internal thoughts or distractions that draw their attention away from the message. For example, if you are preoccupied with personal problems, it is difficult to give your full attention to understanding the message’s meaning. Also, the presence of a person to whom you feel attracted or perhaps to whom you dislike intensely can also create psychological noise.

Physiological Noise

Physiological noise consists of distractions caused by a listener’s own body. For example, maybe you’re listening to a speech in class around noon, and you haven’t eaten anything. Your stomach may be growling, and your desk is starting to look tasty. Maybe the room is cold, and you’re thinking more about how to keep warm than about what the speaker is saying. In either case, your body can distract you from attending to the information being presented.

Semantic Noise

Semantic noise occurs when a listener experiences confusion over the speaker’s meaning or word choice. While you are attempting to understand a particular word or phrase, the speaker continues to present the message. While you are struggling with a word interpretation, you are distracted from listening to the rest of the message. For example, imagine a speaker using the word sweeper to refer to a carpet cleaning device. The listener thinks a sweeper is a broom and does not imagine how effective it would be in cleaning carpeting. Even if the listener found out later that the speaker was using the word sweeper to refer to a vacuum cleaner, her listening was hurt by her inability to understand what the speaker meant. Another example of semantic noise is euphemism. Euphemism is diplomatic language used for delivering unpleasant information. For instance, if someone is said to be “flexible with the truth,” it might take us a moment to understand that the speaker means this person sometimes lies.

Many distractions are neither the listener nor the speaker’s fault. However, when you are the speaker, being aware of these noise sources can help you reduce some noise that may interfere with your audience’s ability to understand you.

Attention Span

A person can only maintain focused attention for a finite length of time. In his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, New York University’s Steinhardt School of Education professor Neil Postman argued that modern audiences have lost the ability to sustain attention to a message (Postman, 1985). More recently, researchers have engaged in an ongoing debate over whether Internet use is detrimental to our attention span (Carr, 2010). Whether or not these concerns are well founded, you have probably noticed that even when your attention is “glued” to something in which you are deeply interested, every now and then you pause to do something else, such as get a drink of water, stretch, or look out the window.

Humans’ attention-span limits can interfere with listening, but listeners and speakers can use strategies to prevent this interference. As many classroom instructors know, listeners will readily renew their attention when the presentation includes frequent pacing breaks (Middendorf & Kalish, 1996). For example, a fifty- to seventy-five-minute class might include some lecture material alternated with questions for class discussion, video clips, handouts, and demonstrations. Instructors who are adept at holding listeners’ attention also move about the front of the room, writing on the board, drawing diagrams, and intermittently using slide transparencies or PowerPoint slides.

If you have instructors who do a good job of keeping your attention, they are positive role models by showing strategies you can use to accommodate your audience’s attention-span limitations.

Receiver Biases

Good listening involves keeping an open mind and withholding judgment until the speaker has completed the message. Conversely, biased listening is characterized by jumping to conclusions. The biased listener believes, “I don’t need to listen because I already know what I think.” Receiver biases can refer to two things: biases with reference to the speaker and preconceived ideas and opinions about the topic or message. Both are noise. Everyone has biases, but good listeners have learned to hold them in check while listening.

The first type of listener bias is related to the speaker. For example, a speaker stands up, and a listener simply doesn’t like the speaker, so that person may not listen to the speaker’s message. Maybe you have a classmate who gets under your skin for some reason, or maybe you question a classmate’s topic competence. When we have preconceived notions about a speaker, those biases can interfere with our ability to listen accurately and competently to the speaker’s message.

The second type of listener bias is related to the speaker’s topic or content. Maybe the speech topic is one you’ve heard a thousand times, so you just tune it out. Or maybe the speaker is presenting a topic or position you fundamentally disagree with. When listeners have strong preexisting opinions about a topic, such as the death penalty, religious issues, affirmative action, abortion, or global warming, their biases may make it difficult for them to even consider new information, especially if the new information is inconsistent with what they already believe to be true. As listeners, we have difficulty identifying our biases, especially when they seem to make sense. However, it is worth recognizing that our lives would be very difficult if no one ever considered new viewpoints or information. We live in a world where everyone can benefit from clear thinking and open-minded listening.

Listener or Receiver Apprehension

Listener or receiver apprehension is the fear that you might not understand the message, process the information correctly, or adapt your thinking to include new information coherently (Wheeless, 1975). In some situations, you might worry that the information presented will be over your head—too complex, technical, or advanced for you to understand adequately.

For example, many students actually avoid taking courses in which they feel certain they will do poorly. Or, they only take challenging courses if it’s required. This avoidance might be understandable, but it is not a good success strategy. To become educated people, students are advised to take a few courses that can enlighten their limited knowledge.

As a speaker, you can reduce listener apprehension by defining terms clearly and by using simple visual aids to hold the audience’s attention. Don’t underestimate or overestimate your audience’s subject knowledge—good audience analysis is always important. If you know your audience doesn’t have special topic knowledge, start your speech by defining important terms. Research has shown that when listeners do not feel they understand a speaker’s message, their apprehension about receiving the message escalates. Imagine that you are listening to a chemistry speech, and the speaker begins talking about “colligative properties.” You may start questioning whether you’re even in the right place. When this happens, apprehension clearly interferes with a listener’s ability to accurately and competently understand a speaker’s message. As a speaker, you can lessen the listener’s apprehension by explaining that colligative properties focus on how much is dissolved in a solution, not on what is dissolved in a solution. You could also give an example that they might readily understand, such as saying that it doesn’t matter what kind of salt you use in the winter to melt driveway ice, what is important is how much salt you use.

What are the stages of listening?

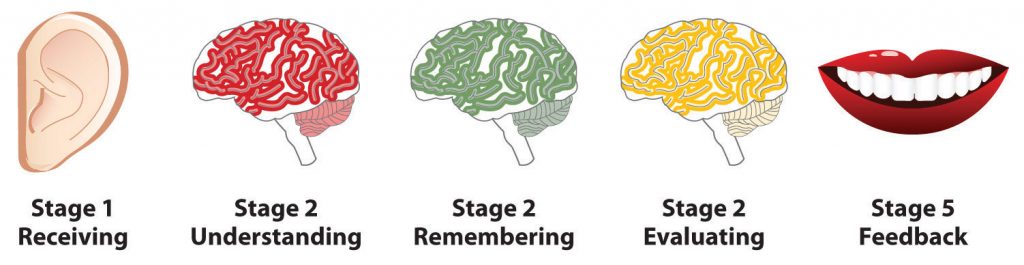

As you read earlier, many factors can interfere with listening, so you need to manage several mental tasks at the same time to be a successful listener. Author Joseph DeVito has divided the listening process into five stages: receiving, understanding, remembering, evaluating, and responding (DeVito, 2000).

Receiving

Receiving is focusing intentionally on hearing a speaker’s message, which happens when we filter out other sources so that we can isolate the message and avoid the confusing mixture of incoming stimuli. At this stage, we are still only hearing the message. Notice in the stages of feedback image that this stage is represented by the ear because it is the primary tool involved with this listening-process stage.

Understanding

In the understanding stage, we attempt to learn the message’s meaning, which is not always easy. For example, if a speaker does not enunciate clearly, it may be difficult to tell what the message was—did your friend say, “I think she’ll be late for class,” or “My teacher delayed the class”? Notice again in the image that stages two, three, and four are represented by the brain because it is the primary tool involved with these listening-process stages.

Even when we have understood a message’s words, because of our different backgrounds and experiences, we sometimes make the mistake of attaching our own meanings to the speakers’ words. For example, say you have made plans with your friends to meet at a certain movie theater, but you arrive and nobody else shows up. Eventually, you learn that your friends are at a different theater across town where the same movie is playing. Everyone else understood that the meeting place was the west side location, but you wrongly understood it as the east side location and therefore missed out on part of the fun.

The consequences of ineffective listening in a classroom can be much worse. When your professor advises you to get an early start on your speech, he or she probably hopes that you will begin your research right away and move on to developing a thesis statement and speech outline as soon as possible. However, other students in your class might misunderstand the instructor’s meaning in several ways. One student might interpret the advice to mean that as long as she gets started, the rest of the assignment will have time to develop itself. Another student might think that to start early means to start on Friday night instead of Sunday night before the Monday due date.

So much of the way we understand others is influenced by our own perceptions and experiences. Therefore, at the listening process’s understanding stage, we should be on the lookout for situations where our perceptions might differ from the speaker’s.

Remembering

Remembering begins with listening. If you can’t remember something that was said, you might not have been listening effectively. Wolvin and Coakley note that the most common reason for not remembering a message after the fact is because it wasn’t really learned in the first place (Wolvin & Coakley, 1996). However, even when you are listening attentively, some messages are more difficult than others to understand and remember. Highly complex messages that are filled with detail call for highly developed listening skills. Moreover, if something distracts your attention even for a moment, you could miss information that explains other new concepts when you begin to listen fully again.

It’s also important to know that you can improve your message memory by processing it meaningfully—that is, by applying it in ways that are meaningful to you (Gluck, et al., 2008). Instead of simply repeating a new acquaintance’s name over and over, for example, you might remember it by associating it with something in your own life. “Emily,” you might say, “reminds me of the Emily I knew in middle school,” or “Mr. Impiari’s name reminds me of the Impala my father drives.”

Finally, if your understanding is inaccurate, recalling the message’s meaning will be inaccurate too.

Evaluating

The fourth stage in the listening process is evaluating or judging the message’s value. We might be thinking, “This makes sense” or, conversely, “This is very odd.” Because everyone embodies biases and perspectives learned from widely diverse life experiences, evaluating the same message can vary widely from one listener to another. Even the most open-minded listeners will have opinions of a speaker, and those opinions will influence how they evaluate the message. People are more likely to evaluate a message positively if the speaker speaks clearly, presents ideas logically, and gives reasons to support the points made.

Unfortunately, personal opinions sometimes cause prejudiced evaluations. Imagine you’re listening to a speech given by someone from another country, and this person has an accent that is hard to understand. You may have a hard time simply making out the speaker’s message. Some people find a foreign accent to be interesting or even exotic, while others find it annoying or even take it as a sign of ignorance. If a listener has a strong bias against foreign accents, the listener may not even attempt to attend to the message. If you mistrust a speaker because of an accent, you could be rejecting important or personally enriching information. Good listeners have learned to refrain from making these judgments and instead have learned to focus on the speaker’s meanings.

Responding

Responding—sometimes referred to as feedback—is the fifth and final listening-process stage. It’s the stage at which you indicate your involvement. Almost anything you do at this stage can be interpreted as feedback. For example, you are giving positive feedback to your instructor if, at the end of class, you stay behind to finish a sentence in your notes or you approach the instructor to ask for clarification. The opposite kind of feedback is given by students who gather their belongings and rush out the door as soon as class is over. Notice once more in the stages of feedback image that this stage is represented by the lips because we often give feedback in the form of verbal feedback; however, you can just as easily respond nonverbally.

Formative Feedback

Not all response occurs at the end of the message. Formative feedback is a natural part of the ongoing transaction between a speaker and a listener. As the speaker delivers the message, a listener signals his or her involvement with focused attention, note-taking, nodding, and other behaviors that indicate whether they understand or fail to understand the message. These signals are important to the speaker. The speaker is interested in whether the message is clear and accepted or whether the listener is resisting the message’s content due to preconceived ideas. Speakers can use this feedback to decide whether they need additional examples, support materials, or explanations.

Summative Feedback

Summative feedback is given at the end of the communication. When you attend a political rally, a presentation given by a speaker you admire, or even a class, there are verbal and nonverbal ways to indicate that you appreciate or disagree with the message or with the speakers. At the end of the message, maybe you’ll stand up and applaud a speaker with whom you agree or just sit staring in silence after listening to a speaker who you didn’t like. In other cases, a speaker may be attempting to persuade you to donate to a charity, so if the speaker passes a bucket, and you make a donation, you are providing feedback on the speaker’s effectiveness. At the same time, we do not always listen carefully to speakers who we admire. Sometimes we simply enjoy being in their presence, and our summative feedback is not about the message but about our attitudes towards the speaker. If your feedback is limited to something like, “I just love your voice,” you might be indicating that you did not listen carefully to the message’s content.

There is little doubt that by now, you are beginning to understand the complexity of listening and the great potential for errors. By becoming aware of what is involved with active listening and where difficulties might lie, you can prepare yourself both as a listener and as a speaker to minimize listening errors with your own public speeches.

There is little doubt that by now you understand how complex active listening can be. But by being aware of the listening stages, recognizing the great potential for errors, and preparing ahead for difficulties, you can become respectful active listeners and deliver compelling, engaging speeches.

How do we listen critically?

As a student, you are exposed to various messages. You receive messages conveying academic information, institutional rules, instructions, and warnings; you also receive messages through political discourse, advertisements, gossip, jokes, song lyrics, text messages, invitations, web links, and more. You know the messages are not all the same—their meaning varies depending on the author’s purpose and audience. But it isn’t always clear which messages are serving the listener and which ones are serving the speaker. Nor is it always clear how to separate truthful messages from the misleading or even blatantly false ones. Part of being a good listener is to learn how to critically evaluate the messages we hear.

Critical listening in this context means using careful, systematic thinking and reasoning to determine whether a message makes sense in light of factual evidence. Critical listening can be learned with practice but, it is not necessarily easy to do. Some people never learn this skill; instead, they take every message at face value even when those messages are in conflict with their knowledge. Problems occur when messages are repeated to others who have not yet developed the skills to discern the difference between a valid message and a mistaken one. Critical listening can be particularly difficult when the message is complex. Unfortunately, some speakers make their messages intentionally complex to avoid critical scrutiny. For example, a city treasurer giving a budget presentation might use very large words and technical jargon, which makes it difficult for listeners to understand the proposed budget and to ask probing questions.

Six Ways to Improve Your Critical Listening Skills

Critical listening is first and foremost a skill that can be learned and improved upon. In this section, we explore six different techniques that you can use to become a skilled critical listener.

Recognizing the Difference between Facts and Opinions

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan is credited with saying, “Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but they are not entitled to their own facts” (Wikiquote). Critical listening requires that you learn to separate opinions from facts. This works two ways: critical listeners are aware of whether a speaker is delivering a factual message or an opinion-based message, and they are also aware of the interplay between their own opinions and the facts they hear.

For example, in American politics, health care reform is heavily laden with both opinions and facts, and it is extremely difficult to sort them out. On September 9, 2010, during President Obama’s nationally televised speech to a joint session of Congress outlining his health care reform plan, the President responded to several rumors about the plan, including the claim “that our reform effort will insure illegal immigrants. This, too, is false—the reforms I’m proposing would not apply to those who are here illegally.” At this point, one congressman yelled out, “You lie!” Clearly, this congressman did not have a very high opinion of either the health care reform plan or the president. However, when the nonpartisan watch group Factcheck.org examined the proposed bill’s language, they found that it had a section titled “No Federal Payment for Undocumented Aliens” (Factcheck.org, 2009).

Often when people have a negative opinion about a topic, they are unwilling to accept facts. Instead, they question all the speech’s aspects and develop a negative predisposition toward both the speech and the speaker.

This is not to say that speakers should not express their opinions. Many of history’s greatest speeches include personal opinions. Consider for example, Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he expressed his personal wish for American society’s future. Critical listeners may agree or disagree with a speaker’s opinions, but the point is that they know when a message they are hearing is based on opinion and when it is factual.

Uncovering Assumptions

If something is factual, supporting evidence exists. However, we still need to be careful about the evidence’s meaning. Assumptions are gaps in a logical sequence that listeners passively fill with their own ideas and opinions and may or may not be accurate. When listening to a public speech, you may find yourself being asked to assume something is a fact when, in reality, many people question that fact. For example, suppose you’re listening to a speech on weight loss. The speaker talks about how overweight people are simply not motivated or lack the self-discipline to lose weight. The speaker has built the speech on the assumption that lack of motivation and self-discipline are the only reasons why people can’t lose weight. You may think to yourself, what about genetics? By listening critically, you will be more likely to notice unwarranted assumptions in a speech, which may prompt you to question the speaker, if questions are encouraged, or to do further research to examine the validity of the speaker’s assumptions. If, however, you sit passively by and let the speaker’s assumptions go unchallenged, you may find yourself persuaded by information that is not factual.

When you listen critically to a speech, you might hear information that appears unsupported by evidence. You shouldn’t accept that information unconditionally. You would accept it under the condition that the speaker offers credible evidence that directly supports it.

Table 4.1 Facts vs. Assumptions

| Facts | Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Facts are verified by clear, unambiguous evidence. | Assumptions are not supported by evidence. |

| Most facts can be tested. | Assumptions about the future cannot be tested in the present. |

Be Open to New Ideas

Sometimes, people are so fully invested in their world perceptions that they are unable to listen receptively to messages that make sense and that would benefit them greatly. Historically, humans as a whole are a creative, curious, innovative, and discerning race who continue to steadily progress new ideas and push unprecedented boundaries, sometimes against great odds. For example, in the late 1700s when the vaccination technique to prevent smallpox was introduced, the protocol was opposed by both medical professionals and everyday citizens who staged public protests (Edward Jenner Museum). More than two centuries later, vaccinations against smallpox, diphtheria, polio, and other infectious diseases have saved countless lives, yet today, much opposition continues.

In the public speaking world, we must be open to new ideas. Let’s face it, people have a tendency to filter out information they disagree with and to filter in information that supports what they already believe. Nicolaus Copernicus was a sixteenth-century astronomer who dared to publish a treatise explaining that the earth revolves around the sun, which was a violation of Catholic doctrine. Copernicus’s astronomical findings were labeled heretical, and his treatise banned because a group of people at the time were not open to new ideas. In May of 2010, almost five hundred years after Copernicus’s death, the Roman Catholic Church admitted its error and reburied his remains with the full Catholic burial rites (Owen, 2010).

While the Copernicus case is a fairly dramatic reversal, listeners should always be open to new ideas. We are not suggesting that you have to agree with every idea that is presented to you in life; rather, we are suggesting that you at least listen to and then evaluate the message.

Rely on Reason and Common Sense

If you are listening to a speech and your common sense tells you that the message is illogical, you very well might be right. Think about whether the speech seems credible and coherent. In this way, your common sense can act as a warning system for you.

For example, consider a speech on the environmental hazards of fireworks. The speaker argues that fireworks—the public kind, not the personal kind people buy and set off in their backyards, were environmentally hazardous because of the after litter. Although there is certainly some unburned paper that makes it to the ground, the litter created by fireworks displays is relatively small compared to other litter sources, including the trash that spectators leave behind after watching the fireworks at public parks and other venues. It just does not make sense to identify a few bits of charred paper as a major environmental hazard.

If the message is inconsistent with what you already know, if the argument is illogical, or if the language is exaggerated, investigate the issues before accepting or rejecting the message. Often, you will not be able to investigate facts during the presentation; it may take longer to collect enough verifiable, clear, and unambiguous evidence to make that decision for yourself.

However, when you are the speaker, do not substitute common sense for evidence. During a speech, it’s necessary to cite the scholarly authorities whose research is irrefutable, or at least highly credible. It is all too easy to make a mistake in reasoning, sometimes called fallacy, in stating your case. We will discuss these fallacies in more detail in Chapter 17. One of the most common fallacies is post hoc, ergo propter hoc, a common sense form of logic that translates roughly as “after the fact, therefore because of the fact.” The argument says that if A happened first, followed by B, then A caused B. We know the outcome cannot occur earlier than the cause, but we also know that the two events might be related indirectly or that causality works in a different direction. For instance, imagine a speaker arguing that because the sun rises after a rooster’s crow, the rooster caused the sun to rise. This argument is clearly illogical because roosters crow many times each day, and the sun’s rising and setting do not change according to crowing or lack thereof. But the two events are related in a different way. Roosters tend to wake up and begin crowing at first light, about forty-five minutes before sunrise. Thus, it is the impending sunrise that causes the predawn crowing.

In Chapter 2, we pointed out that what is common sense for people of one generation or culture may be quite the opposite for people of a different generation or culture. Thus, it is important not to assume that your audience shares the beliefs that are, for you, common sense. Likewise, if your speech’s message is complex or controversial, consider your audience’s needs and do your best to explain the complexities factually and logically, not intuitively.

Relate New Ideas to Old Ones

As both a speaker and a listener, one of the most important things you can do to understand a message is to relate new ideas to previously held ideas. Imagine you’re giving a speech about biological systems, and you need to use the term homeostasis, which refers to an organism’s ability to maintain stability by making constant adjustments. To help your audience understand homeostasis, you could show how homeostasis is similar to adjustments made by the thermostats that keep our homes at a more or less even temperature. If you set your thermostat for seventy degrees, and it gets hotter, the central cooling will kick in and cool your house. If your house cools to below seventy degrees, your heater will kick in and heat your house. Notice that in both cases, your thermostat is making constant adjustments to stay at seventy degrees. Explaining that the body’s homeostasis works in a similar way will make it more relevant to your listeners and will likely help them both understand and remember the idea because it links to something they have already experienced.

Making effective comparisons while you are listening to a message will deepen your understanding. As the speaker, if you provide comparisons for your listeners, you make it easier for them to consider your ideas.

Take Notes

Note-taking is a skill that improves with practice. You already know that it’s nearly impossible to write down everything a speaker says. In fact, in your attempt to record everything, you might fall behind and wish you had divided your attention differently between writing and listening.

Careful, selective note-taking is important because we want an accurate record that reflects the message’s meanings. However much you might concentrate on the notes, you could inadvertently leave out an important word, such as not, and undermine the reliability of your otherwise carefully written notes. Instead, if you give the same care and attention to listening, you are less likely to make those mistakes.

It’s important to find a balance between listening well and note-taking well. Many people constantly struggle with this balance. For example, if you try to write down only key phrases instead of full sentences, you might find that you can’t remember how two ideas were related. In that case, too few notes were taken. Conversely, extensive note-taking can cause you to lose the most important idea’s emphasis.

To increase your critical listening skills, continue developing your ability to identify a message’s central issues so that you can take accurate notes that represent the speaker’s intended meaning.

Listening Ethically

Ethical listening rests heavily on honest intentions. Extend to speakers the same respect you want to receive when it’s your turn to speak. Face the speaker with open eyes. Don’t constantly check your cell phone. Avoid any behavior that belittles the speaker or the message.

Scholars Stephanie Coopman and James Lull emphasize creating a climate of caring and mutual understanding, observing that “respecting others’ perspectives is one hallmark of the effective listener” (Coopman & Lull, 2008). Respect, or unconditional positive regard for others, means that you treat others with consideration and decency whether you agree with them or not. Professors Sprague, Stuart, and Bodary (Sprague, et al., 2010), also urge us to treat the speaker with respect even when we disagree, don’t understand the message, or find the speech boring.

Doug Lippman (1998) (Lippman, 1998), a storytelling coach, wrote powerfully and sensitively about listening in his book:

“Like so many of us, I used to take listening for granted, glossing over this step as I rushed into the more active, visible ways of being helpful. Now, I am convinced that listening is the single most important element of any helping relationship.

Listening has great power. It draws thoughts and feelings out of people as nothing else can. When someone listens to you well, you become aware of feelings you may not have realized that you felt. You have ideas you may have never thought before. You become more eloquent, more insightful.…

As a helpful listener, I do not interrupt you. I do not give advice. I do not do something else while listening to you. I do not convey distraction through nervous mannerisms. I do not finish your sentences for you. In spite of all my attempts to understand you, I do not assume I know what you mean.

I do not convey disapproval, impatience, or condescension. If I am confused, I show a desire for clarification, not dislike for your obtuseness. I do not act vindicated when you misspeak or correct yourself.

I do not sit impassively, withholding participation.

Instead, I project affection, approval, interest, and enthusiasm. I am your partner in communication. I am eager for your imminent success, fascinated by your struggles, forgiving of your mistakes, always expecting the best. I am your delighted listener” (Lippman, 1998).

This excerpt expresses the decency with which people should treat each other. It doesn’t mean we must accept everything we hear, but ethically, we should refrain from trivializing each other’s concerns. We have all had the painful experience of being ignored or misunderstood. This is how we know that one of the greatest gifts one human can give to another is listening well.

References

Carr, N. (2010, May 24). The Web shatters focus, rewires brains. Wired Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/magazine/2010/05/ff_nicholas_carr/all/1.

Jarvis, T. (2009, November). How to talk so people really listen: Four ways to make yourself heard. O, the Oprah Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.oprah.com/relationships/Communication-Skills-How-to-Make-Yourself-Heard

Middendorf, J., & Kalish, A. (1996). The “change-up” in lectures. The National Teaching and Learning Forum, 5(2).

Postman, N. (1985). Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the age of show business. New York: Viking Press.

University of Minnesota. (2011). Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Wheeless, L. R. (1975). An investigation of receiver apprehension and social context dimensions of communication apprehension. Speech Teacher, 24, 261–268.

Media References

Feggy Art. (2009, October 1). One and Other-Plinth Telephone System & Guitar Playing [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/victius/4027766870/in/photolist-78VmLo-78RtYg-78RsKx-78Ru1i-78VmQ5-78Ru7i-78RsQx-78VmB7-78VkmU-78Rt3e-78VnsA-78RtMk-GVxFRW-78Rtyk-73JAQV-72e4PM-78Vm2E-Rra6x7-bGox2e-bttGJj-bGov18-bGowDB-bttGF1-bGowN6-y1Zfv4-x4ikvh-bGovGT-xHGGP1-bGovyD-bGovdg-bDSQx-bttGZb-bGovVX-bGowoP-8pNrVX-bttHRQ-bttGQy-bttFZL-bGovPP-SE2kMS-bttHju-bttH3E-bGowUM-bttGkm-bttFos-bGoxz2-bttHtQ-bttFBU-bGowsa-bGouzD

Graves, Z. (2007, July 16). The importance of listening [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/basictheory/849024061/

Howard, K. (2004, November 13). Megaphone [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kimba/1450769/

King, Cherise. (no date). Chinese Character for Listen [Image].

Kizzzbeth. (2011, September 24). Good Listener [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/31403417@N00/6201411854/

McFarland, I.T. (2009, August 15). Listen [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedestrianrex/3864438541/

Mills, A. (no date). Seven, people, meeting, office [Image]. Pixnio. https://pixnio.com/people/seven-people-at-meeting-on-office

TED. (2011, May). The happy secret to better work [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/shawn_achor_the_happy_secret_to_better_work#t-21844

Unknown. (2011). Hearing vs. Listening [Image]. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, University of Minnesota. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/4-1-listening-vs-hearing/

Unknown. (2011). Stages of Feedback [Image]. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, University of Minnesota. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/4-4-stages-of-listening/#wrench_1.0-ch04_s04_f01

Unknown. (2011). Types of Noise [Image]. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, University of Minnesota. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/4-3-why-listening-is-difficult/