Chapter 3: Managing Speech Anxiety

This chapter, except where otherwise noted, is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

How do I manage my speech anxiety?

Now that you have an understanding of how important it is for you to use ethical principles in creating an effective speech, let’s move to the topic you have all been either dreading or can’t wait to learn about: how to manage speech anxiety.

Take a look at this scene from the Albert Meets Hitch video and see if you can relate to how nervous these people are.

Hitch: Albert meets Hitch HD CLIP, by Binge Society – The Greatest Movie Scenes, Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MIBzVc3kJAM

You can imagine how much better this interaction would have gone had the participants not been so anxious. The question is, is it possible to manage your speech anxiety during a conversation, a job interview, or a speech?

Speech Anxiety/Communication Apprehension

Many different social situations can make us feel uncomfortable if we anticipate that we will be evaluated and judged by others. The process of revealing ourselves and knowing that others are evaluating us can be threatening whether we are meeting new acquaintances, participating in group discussions, or speaking in front of an audience.

Definition of Communication Apprehension

According to James McCroskey, communication apprehension is the broad term that refers to an individual’s “fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (McCroskey, 2001). At its heart, communication apprehension is a psychological response to evaluation. This psychological response, however, quickly becomes physical as our body responds to the threat the mind perceives. Our bodies cannot distinguish between psychological and physical threats, so we react as though we are facing a Mack truck barreling in our direction. The body’s circulatory and adrenal systems shift into overdrive, preparing us to function at maximum physical efficiency, kicking in the “flight or fight” response (Sapolsky, 2004). Yet instead of running away or fighting, all we need to do is stand and talk.

The excess energy our body creates can make it harder for us to be effective public speakers. But because communication apprehension is rooted in our minds, if we understand more about the body’s responses to stress, we can better develop mechanisms for managing the body’s misguided attempts to help us cope with social judgment fears.

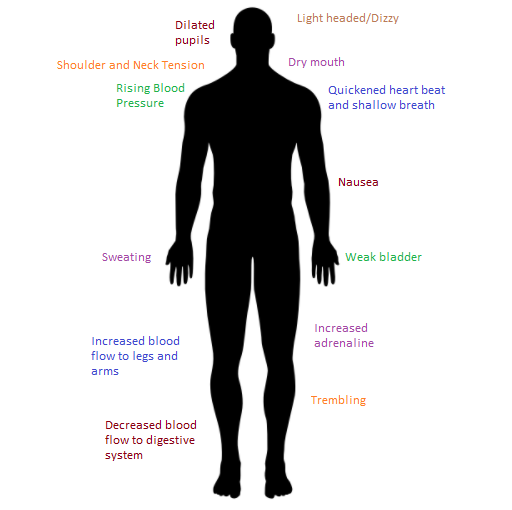

Physiological Symptoms of Communication Apprehension

There are various physical sensations associated with communication apprehension. We might notice our heart pounding or our hands feeling clammy. We may break out in a sweat, have stomach butterflies, or even feel nauseated. Our hands and legs might start to shake, or we may begin to pace nervously. Our voices may quiver, and we may have a dry-mouth sensation that makes it difficult to articulate even simple words. Breathing becomes more rapid, and, in extreme cases, we might feel dizzy or light-headed. Communication anxiety is profoundly disconcerting because we feel powerless to control our bodies. We may become so anxious that we fear we will forget our name, much less remember the main points of the speech we are about to deliver.

The physiological changes our bodies produce at critical moments are designed to contribute to ensure our muscles work efficiently and expand available energy. Circulation and breathing become more rapid so that additional oxygen can reach the muscles. Increased circulation causes us to sweat. Adrenaline rushes through our body, instructing the body to speed up its movements. If we stay immobile behind a lectern, this hormonal urge to speed up may produce shaking and trembling. Additionally, digestive processes are inhibited so we will not lapse into the relaxed, sleepy state that is typical after eating. Instead of feeling sleepy, we feel butterflies in the pit of our stomach. By understanding what is happening to our bodies in response to public speaking stress, we can better cope with these reactions and channel them in constructive directions.

Watch this Ted Ed video, The Science of Stage Fright by Mikael Cho. In it, Cho shares what physically happens when we become anxious. It is now called the “fight, flight, or freeze” response because sometimes we hold very still when frightened.

The video can make you feel scared just watching it, but try and notice that there is an actual science to stage fright or speech anxiety, and you are not alone in feeling nervous or scared.

Pay particular attention near the end when Cho gives you one option to help manage your anxiety.

The science of stage fright (and how to overcome it) – Mikael Cho, by TED-Ed, Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K93fMnFKwfI

After watching the video, did you realize that anxiety is a normal human reaction? We can help reduce the anxiety, but not totally eliminate it. As you continue with this module you will learn strategies to reduce anxiety.

- Any conscious emotional state, such as anxiety or excitement consists of two components:

- A primary reaction of the central nervous system.

- An intellectual interpretation of these physiological responses.

The physiological state we label as communication anxiety does not differ from those that we label rage or excitement. Even seasoned effective speakers and performers experience some communication apprehension. What differs is the mental label that we put on the experience. Effective speakers have learned to channel their body’s reactions, using the energy released by these physiological reactions to create animation and stage presence.

It has been documented that famous speakers throughout history such as Cicero, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, Eleanor Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Gloria Steinem conquered significant public speaking fears. Celebrities who experience performance anxiety include actor Harrison Ford, Beyonce, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Rihanna, Matt Damon, and George Clooney (Hickson, 2016).

Myths about Communication Apprehension

Before we look at how to manage our speech anxiety, let’s dispel some myths.

- People who suffer from speaking anxiety are neurotic. As we have explained, speaking anxiety is a normal reaction. Good speakers can get nervous, too, just as poor speakers do.

- Telling a joke or two is always a good way to begin a speech. Humor is some of the toughest material to deliver effectively because it requires an exquisite sense of timing. Nothing is worse than waiting for a laugh that does not come. Moreover, one person’s joke is another person’s slander. It is extremely easy to offend when using humor. The same material can play very differently with different audiences. For these reasons, it is not a good idea to start with a joke, particularly if it is not well related to your topic. Humor is just too unpredictable and difficult for many novice speakers. If you insist on using humor, make sure the joke is on you, not on someone else. Another tip is never to pause and wait for a laugh that may not come. If the audience catches the joke, fine. If not, you’re not left standing in awkward silence waiting for a reaction.

- Imagine the audience is naked. This tip just plain doesn’t work because imagining the audience naked will do nothing to calm your nerves. The audience is not some abstract image in your mind. It consists of real individuals who you can connect with through your material.

- Any mistake means that you have “blown it.” We all make mistakes. What matters is how well we recover, not whether we make a mistake. A speech does not have to be perfect. You just have to make an effort to relate to the audience naturally and be willing to accept your mistakes.

- Audiences are out to get you. An audience’s natural state is empathy, not antipathy. Most face-to-face audiences are interested in your material, not in your image. Watching someone who is anxious tends to make audience members anxious themselves. Particularly in public speaking classes, audiences want to see you succeed. They know that they will soon be in your shoes, and they identify with you, most likely hoping you’ll succeed and give them ideas for how to make their own speeches better. If you establish direct eye contact with real individuals in your audience, you will see them respond to what you are saying, and this response lets you know that you are succeeding.

- You will look as nervous as you feel. Empirical research has shown that audiences do not perceive the level of nervousness that speakers report feeling (Clevenger, 1959). Most listeners judge speakers as less anxious than the speakers rate themselves. In other words, the audience is not likely to perceive accurately your anxiety level. Some of the most effective speakers will return to their seats after their speech and exclaim they were so nervous. Listeners will respond, “You didn’t look nervous.” Audiences do not necessarily perceive our fears. Consequently, don’t apologize for your nerves. There is a good chance the audience will not notice that you’re nervous if you do not point it out to them.

- TRUE. A little nervousness helps you give a better speech. This myth is true! Professional speakers, actors, and other performers consistently rely on their nervous heightened arousal to channel extra energy into their performance. People would much rather listen to a speaker who is alert and enthusiastic than one who is relaxed to the point of boredom. Many professional speakers say that the day they stop feeling nervous is the day they should stop public speaking. The goal is to control those nerves and channel them into your presentation.

Common yet unexpected difficulties can increase speech anxiety: how do we cope?

The following sections are adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Speech Content Issues

Nearly every experienced speaker has gotten to the middle of a presentation and realized that a key notecard is missing or that he or she skipped important information from the speech’s beginning. When encountering these difficulties, a good strategy is to pause for a moment to think through what you want to do next. Is it important to include the missing information, or can it be omitted without hurting the audience’s ability to understand the rest of your speech? If it needs to be included, do you want to add the information now, or will it fit better later in the speech? It is often difficult to remain silent when you encounter this situation, but pausing for a few seconds will help you to figure out what to do and may be less distracting to the audience than sputtering through a few “ums” and “uhs.”

Technical Difficulties

Technology has become a very useful public speaking aid, allowing us to use audio or video clips, presentation software, or direct links to websites. However, one of the best-known truisms about technology is that it can and does break down. Web servers go offline, files will not download in a timely manner, and media are incompatible with the presentation room’s computer. It is important to always have a backup plan, developed in advance, in case of technical difficulties. As you develop your speech, visual aids, and other presentation materials, think through what you will do if you cannot show a particular graph or if your presentation slides are hopelessly garbled. Although your beautifully prepared chart may be superior to the oral description you can provide, your ability to provide a succinct oral description when technology fails can give your audience the information they need.

External Distractions

Although many public speaking instructors directly address audience etiquette, you’re still likely to experience an audience member walking in late, a cell phone ringing, or even a car alarm blaring outside your room. If you are distracted by external events like these, it is often useful, and sometimes necessary—as in the case of the loud car alarm—to pause and wait so that you can regain the audience’s attention and be heard.

Whatever the unexpected event, as the speaker, your most important job is to maintain your composure. It is important not to get upset or angry because of these glitches—and, once again, the key is to be fully prepared. If you keep your cool and quickly implement a plan B for moving forward with your speech, your audience is likely to be impressed and may listen even more attentively to the rest of your presentation.

The following sections are adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Anticipate Your Body’s Reactions

There are various steps you can take to counteract stress’ negative physiological effects on the body. You can place words and symbols in your notes that remind you to pause and breathe during points in your speech, such as “slow down” or ☺.

It is also a good idea before you get started to pause a moment to set an appropriate pace from the onset. Look at your audience and smile. It is a reflex for some of your audience members to smile back. Those smiles will reassure you that your audience members are friendly.

Physical movement helps to channel some of the excess anxiety-induced energy that your body produces. If at all possible, move around the front of the room rather than remaining imprisoned behind the lectern or gripping it for dear life; however, avoid pacing nervously from side to side. Move closer to the audience and then stop for a moment. If you are afraid that moving away from the lectern will reveal your shaking hands, use note cards rather than a sheet of paper for your outline. Note cards do not quiver like paper, and they provide you with something to do with your hands.

Vocal warm-ups are also important to do before speaking. Just as athletes warm up before practice or competition and musicians warm up before playing, speakers need to get their voices ready to speak. Talking with others before your speech or quietly humming to yourself can get your voice ready for your presentation. You can even sing or practice a bit of your speech out loud while you’re in the shower, where the warm, moist air is beneficial for your vocal mechanism. Gently yawning a few times is also an excellent way to stretch the key muscle groups involved in speaking.

Immediately before you speak, you can relax your neck and shoulder muscles by gently rolling your head from side to side.

Focus on the Audience, Not on Yourself

During your speech, make a point of establishing direct eye contact with your audience members. By looking at individuals, you establish a series of one-to-one contacts similar to interpersonal communication.

The Magic of Science

Now for some scientific managing-speech-anxiety magic. You are welcome to use what you hear in your own plan if you choose. Take a listen to Harvard Professor Amy Cuddy and a surprising two-minute strategy that many students find very effective. It is worth watching the full twenty-minute video, Your Body Language May Shape Who You Are.

Amy Cuddy: Your Body Language May Shape Who You Are, by TEDGlobal 2012, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Yes, two minutes, two minutes, two minutes. Remember the audience is more interested in learning about what you have to say than in judging you. So, forget yourself and be there for the audience.

Note: Are you a good people watcher? I hope you are because it will aid your progress as a speaker. You will be viewing video clips of speakers throughout the course. Pay attention to what went well in a speech and what you would recommend a speaker change to make their speech better.

For example, In Amy Cuddy’s speech, her data visual aids helped in better understanding the speech. Did you notice where her hair was? Would you recommend she do something different with it? Notice, notice, notice. It will help you know what you want to do and not do in your own speeches.

References

Ackrill, C. (2012, October 5). 6 thought patterns of the stressed: No. 3 – catastrophizing. American Institute of Stress. Retrieved from http://www.cynthiaackrill.com/6-thought-patterns-of-the-stressed-no-3-catastrophizing-lions-and-tigers-and-bears-oh-my/

Allen, M., Hunder, J.E., & Donohue, W.A. (2009). Meta-analysis of self-report data on the effectiveness of public speaking anxiety treatment techniques. Communication Education, 38, 54–76.

Ayres, J. (2005). Performance visualization and behavioral disruption: A clarification. Communication Reports, 18 55–63.

Ayres, J., & Hopf, T. (1995). Coping with speech anxiety. Norwood, NJ: Ablex

Bodie, G.D. (2010). A racing heart, rattling knees, and ruminative thoughts: Defining, explaining, and treating public speaking anxiety. Communication Education, 59, 70–105.

Boyes, A. (2013a, March 13). 6 tips for overcoming anxiety-related procrastination. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-practice/201303/6-tips-overcoming anxiety-related-procrastination

Boyes, A. (2013b, January 10). What is catastrophizing? Cognitive distortions. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-practice/201301/what-is-catastrophizing-cognitive-distortions

Cunningham, V., Lefkoe, M., & sechrest, L. (2006). Eliminating fears: An intervention that permanently eliminates the fear of public speaking. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 13, 183–193

Dean, J. (2012, October 10). The illusion of transparency. PsyBlog. Retrieved from http://www.spring.org.uk/2012/10/the-illusion-of-transparency.php

Ellis, A. (1995). Thinking processes involved in irrational beliefs and their disturbed consequences. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 9, 105 –116.

Ellis, A. (1996). How I learned to help clients feel better and get better. Psychotherapy, 33, 149–151.

Finn, A.N., Sawyer, C.R, & Schrodt, P. (2009). Examining the effect of exposure therapy on public speaking state anxiety. Communication Education, 58, 92–109.

Grohol, J.M. (2013). What is catastrophizing? Psych Central. Retrieved from http://psychcentral.com/lib/what-is-catastrophizing/1276/

Holmes, E.A., & Mathews, A. (2005). Mental imagery and emotion: A special relationship? Emotion, 5, 489–497.

Horowitz, B. (2002). Communication apprehension: Origins and management. Albany, NY: Singular.

Jones, C.R., Fazio, R.H., & Vasey, M.W. (2012). Attention control buffers the effect of public-speaking anxiety on performance. Social Psychology & Personality Science, 3, 556–561.

Lucas, S. E. (2012). The art of public speaking. (11th ed.). McGrawHill.

MacInnis, C.C., MacKinnon, S.P., & MacIntyre, P.D. (2010). The illusion of transparency and normative beliefs about anxiety during public speaking. Current Research in Social Psychology, 15(4). Retrieved from http://www.uiowa.edu/~grpproc/crisp/crisp15_4.pdf

Motley, M.T. (1995). Overcoming your fear of public speaking: A proven method. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Motley, M.T. (1997). COM Therapy. In J.A. Daly, J.C. McCroskey, J.Ayres, T. Hopf, & D.M. Ayres (Eds.) Avoiding communication. Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Motley, M.T. (2011, January 18). Reducing public speaking anxiety: The communication orientation. YouTube. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYfHQvi2NAg

Noonan, P. (1998). Simply speaking: How to communicate your ideas with style, substance, and clarity. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

O’Donohue, W.T., & Fisher, J.E. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy: Applying empirically supported techniques in your practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Pertaub, D., Slater, M., & Barker, C. (2002). An experiment on public speaking anxiety in response to three different types of virtual audiences. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 11, 670–678.

Peterson, C. (2000). The future of optimism. American Psychologist, 55, 44–55.

Prochow, H.V. (1944). Great stories from great lives. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

Roby, D.E. (2009). Teacher leadership skills: An analysis of communication apprehension. Education, 129, 608–614. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ871611

Sandburg, C. (2002). Abraham Lincoln: The prairie years and the war years. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Savitsky, K., & Gilovich, T. (2003). The illusion of transparency and the alleviation of speech anxiety. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 618–625.

Seim, R.W., Waller, S.A., & Spates, R.C. (2010). A preliminary investigation of continuous and intermittent exposures in the treatment of public speaking anxiety. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 6, 84–94.

Spiegler, M.D., & Guevremont, D.C. (1998). Contemporary behavior therapy. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Svoboda, E. (2009, February/March). Avoiding the big choke. Scientific American Mind, pp. 36–41.

Tan Chin Keok, R. (2010, November 25–27). Public speaking: A case study of speech anxiety in L1 and L2. Seminar Penyelidikan Pendidikan Pasca Ijazah.

Witt, P.L., & Behnke, R.R. (2006). Anticipatory speech anxiety as a function of public speaking assignment type. Communication Education, 55, 167–177.

Witt, P.L., Brown, K.C., Roberts, J.B., Weasel, J., Sawyer, C.R., & Behnke, R.R. (2006). Somatic anxiety patterns before, during, and after giving a public speech. Southern Communication Journal, 71, 87–100.

Young, M.J., Behnke, R.R., & Mann, Y.M. (2004). Anxiety patterns in employment interviews. Communication Reports, 17, 49–57.

Media References

(no date). man, portrait, grown up, people, smiling, facial hair, one person, beard, looking at camera, emotion [Image]. pxfuel. https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-ehnup

Binge Society – The Greatest Movie Scenes. (2020, November 6). Hitch: Albert meets Hitch HD CLIP [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MIBzVc3kJAM

Cherise King. (no date). Physiological Symptoms of Communication Apprehension [Image].

Freddie Peña. (2010, 10 July). Nervous? [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fixem/4815843665/

TED. (2012, June). Amy Cuddy: Your body language may shape who you are [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_may_shape_who_you_are?language=en

TED-Ed. (2013, October 8). The science of stage fright (and how to overcome it) – Mikael Cho [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K93fMnFKwfI

www.audio-luci-store.it. (2012, 19 June). Speaker at Podium [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/audiolucistore/7403735392/