Chapter 2: Ethics in Public Speaking

This chapter, except where otherwise noted, is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

What are the objectives of ethical speaking?

Now that you’ve learned the foundations of public speaking, you know that creating a speech involves more than just slapping some facts together and hoping your audience listens. In this module, we move on to explore a core element of public speaking: the importance of ethical communication. We’ve all heard advertisers, received a sales pitch, and listened to politicians who try and persuade us to take some action. But how do we know these are ethical communications? Speechmakers may manipulate facts, present one-sided arguments, and even lie to persuade their audience. And the audience may be fooled if they are not listening critically. None of these actions involve ethical communication. When speakers do not speak ethically, they taken advantage of their audience. When an audience does not listen critically, they disrespect the speaker.

In this module, we will explore what it means to be both an ethical speaker and an ethical listener. You can ethically and effectively persuade. And you can take responsibility to be ethically informed. We will show you how.

Ethical Speaking

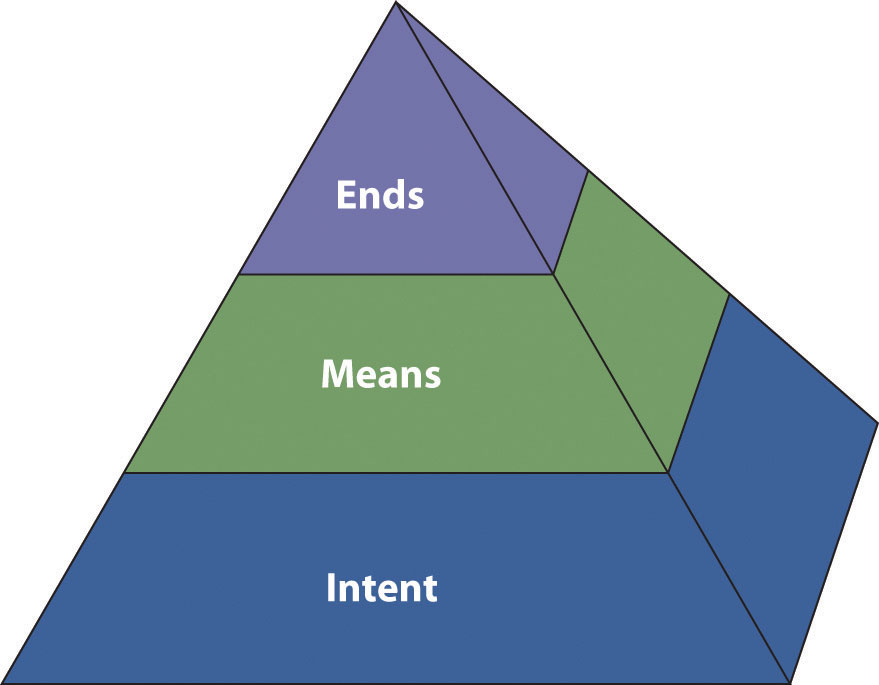

Every day, people around the world make ethical decisions regarding public speech, for example, is it ever appropriate to lie if it’s in a group’s best interest? Should you use evidence to support your speech’s core argument when you are not sure if the evidence is correct? Should you refuse to listen to a speaker with whom you fundamentally disagree? These three examples represent ethical choices that speakers and listeners face in the public speaking context. To help you understand the issues involved with thinking about ethics, we begin this module by presenting an ethical communications model, known as the ethics pyramid. We will then show how you can apply the National Communication Association’s (NCA) Credo for Ethical Communication to public speaking. We will conclude with a general free speech discussion.

The Ethics Pyramid

One way to talk about ethics is to use the ethics pyramid. What is the ethics pyramid?

Elspeth Tilley, a public communication ethics expert from Massey University, proposes a structured approach to thinking about ethics (Tilley, 2005). Her ethics pyramid involves three basic concepts: intent, means, and ends.

Intent

According to Tilley, intent is the first major concept to consider when examining an issue’s ethicality. To be an ethical speaker or listener, it is important to begin with ethical intentions. For example, if we agree that honesty is ethical, it follows that ethical speakers will prepare their remarks with the intent to tell the truth to their audiences. Similarly, if we agree that it is ethical to listen with an open mind, it follows that ethical listeners will intend to hear a speaker’s case before forming judgments.

Many professional organizations, including the Independent Computer Consultants Association, American Counseling Association, and American Society of Home Inspectors, have codes of conduct or ethical guidelines for their members. Individual corporations such as Monsanto, Coca-Cola, Intel, and ConocoPhillips also have ethical guidelines for how their employees should interact with suppliers or clients.

It is important to be aware that people can unintentionally engage in unethical behavior. For example, suppose we agree that it is unethical to take someone else’s words and pass them off as your own—a behavior known as plagiarism. What happens if a speaker makes a statement that he believes he thought of on his own, but the statement is actually quoted from a radio commentator whom he heard without clearly remembering doing so? The plagiarism is unintentional, but does that make it ethical?

Means

Tilley describes the means you use to communicate with others as the ethics pyramid’s second concept. According to McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond, “means are the tools or behaviors we employ to achieve a desired outcome” (McCroskey, Wrench, & Richmond, 2003). Some means are good and some bad.

For example, suppose you want your friend Marty to spend an hour reviewing your speech. What means might you use to persuade Marty to do you this favor? You might explain to Marty’s that you value his opinion and will gladly return the favor when Marty prepares his speech (good means), or you might inform Marty that you’ll tell his professor that he cheated on a test (bad means). While both of these means may lead to the same end—Marty agrees to review your speech—one is clearly more ethical than the other.

Ends

Ends is the ethics pyramid s third concept. According to McCroskey, Wrench, and Richmond (McCroskey, Wrench, & Richmond, 2003), “ends are those outcomes that you desire to achieve.” Ends might include the following:

- Persuading your audience to make a financial contribution for you to participate in Relay for Life.

- Persuading a group of homeowners that your real estate agency would best meet their needs.

- Informing your fellow students about newly required university fees.

Whereas the means are the behavioral choices we make, the ends are the results of those choices.

Like intent and means, ends can be good or bad. For example, suppose a city council wants to balance the city’s annual budget. Balancing the budget may be a good end, assuming that the city has adequate tax revenues and some discretionary spending for city services. However, voters might argue that balancing the budget is a bad end if the city lacks the tax revenue and must raise taxes or cut essential city services, or both, to do so.

What are the guidelines for ethical speaking?

Steven Lucas, a well-known speech instructor, put together five helpful guidelines to ensure ethical speechmaking (Lucas, 2012, pp. 31-35).

- Make sure your goals are ethically sound. Are you asking your audience to do something you yourself do not believe in, do not think is good for the audience, or would not do yourself?

- Be fully prepared for each speech. Don’t cheat the audience by just winging it. If you calculate the money each person in your audience makes during the time you speak, do you want to waste that much of their time and money? As speakers we have a solemn responsibility to make that time worthwhile.

- Be honest in what you say. Speechmaking rests on the assumption that words can be trusted and that people will be truthful. Without this assumption, there is no basis for communication and no reason for one person to believe anything that another person says.

- Avoid name-calling and other forms of abusive language. Names leave psychological scars that last for years. Name-calling defames, demeans, or degrades. These words dehumanize people, all of whom should be treated with dignity and respect.

- Put ethical principles into practice. Being ethical means behaving ethically all the time—not only when it’s convenient (Lucas, 2012, pp.34-35).

Your audience is watching you even when you are not speechmaking. If you try to be honest in your speeches, yet an audience member observes you lying to a classmate, what does that do to your credibility as an ethical speaker? Something to consider.

A Speaker’s Ethical Obligation

According to Lucas, “Name-calling and abusive language pose ethical problems in public speaking when they are used to silence opposing voices. A democratic society depends upon open expression of ideas. In the United States, all citizens have the right to join in democracy’s never-ending dialogue. As a public speaker, you have an ethical obligation to help preserve that right by avoiding tactics such as name-calling, which inherently impugn the accuracy or respectability of public statements made by groups or individual who voice opinions different from yours.

“The obligation is the same whether you are black or white, Christian or Muslim, male or female, gay or straight, liberal or conservative. A pro-union public employee who castigated everyone opposed to her ideas as an “enemy of the middle class” is unethical. A politician who labels all his adversaries “tax-and-spend liberals” is unethical. Although name-calling can be hazardous to free speech, it is still protected under the Bill of Right’s free-speech clause.

Nevertheless, it will not alter the ethical responsibility of public speakers on or off campus to avoid name-calling and other kinds of abusive language” (Lucas, 2012, pp.34-35).

Important Ethical Principles

The largest communication organization in the United States and second largest in the world created an ethical credo outlining important principles to follow if we want to be ethical communicators. Notice how they indicate that ethical speaking takes courage.

National Communication Association Credo for Ethical Communication

Questions of right and wrong arise whenever people communicate. Ethical communication is fundamental to responsible thinking, decision making, and the development of relationships and communities within and across contexts, cultures, channels, and media. Moreover, ethical communication enhances human worth and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others. We believe that unethical communication threatens the quality of all communication and consequently the well-being of individuals and the society in which we live. Therefore we, the members of the National Communication Association, endorse and are committed to practicing the following principles of ethical communication:

- We advocate truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication.

- We endorse freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and tolerance of dissent to achieve the informed and responsible decision making fundamental to a civil society.

- We strive to understand and respect other communicators before evaluating and responding to their messages.

- We promote access to communication resources and opportunities as necessary to fulfill human potential and contribute to the well-being of families, communities, and society.

- We promote communication climates of caring and mutual understanding that respect the unique needs and characteristics of individual communicators.

- We condemn communication that degrades individuals and humanity through distortion, intimidation, coercion, and violence, and through the expression of intolerance and hatred.

- We are committed to the courageous expression of personal convictions in pursuit of fairness and justice.

- We advocate sharing information, opinions, and feelings when facing significant choices while also respecting privacy and confidentiality.

- We accept responsibility for the short- and long-term consequences of our own communication and expect the same of others.

Applying Ethical Principles

Use reason and logical arguments. While there are cases where speakers have blatantly lied to an audience, it is more common for speakers to prove a point by exaggerating, omitting facts that weigh against their message, or distorting information. We believe that speakers build a relationship with their audiences, and that lying, exaggerating, or distorting information violates this relationship. Ultimately, a speaker will be more persuasive by using reason and logical arguments.

Choose objective sources. It is also important to be honest about where you get your information. As speakers, examine your sources and research and determine whether they are biased or have hidden agendas. For example, you are not likely to get accurate information about nonwhite individuals from a neo-Nazi website. While you may not know all your sources firsthand, you should attempt to find objective sources that do not have an overt or covert agenda that skews the argument you are making.

Don’t plagiarize. Using someone else’s words or ideas without giving credit is called plagiarism. The word “plagiarism” stems from the Latin word plagiaries, or kidnapper. The consequences for failing to cite sources during public speeches can be substantial. When Senator Joseph Biden was running for president of the United States in 1988, reporters found that he had plagiarized portions of his stump speech from British politician Neil Kinnock. Biden was forced to drop out of the race as a result. More recently, the student newspaper at Malone University in Ohio alleged that university president, Gary W. Streit, had plagiarized material in a public speech. Streit retired abruptly as a result.

Cite your sources. Even if you are not running for president of the United States or serving as a college president, citing sources is important to you as a student. Many universities have policies that include dismissing students from the institution for plagiarizing academic work, including public speeches. Failing to cite your sources might result, at best, in lowering your credibility with your audience and, at worst, in a failing course grade or school expulsion.

Speakers tend to fall into one of three major traps regarding plagiarism.

- The first trap is failing to tell the audience the source of a direct quotation.

- The second trap is paraphrasing what someone else said or wrote without giving credit to the speaker or author. For example, you may have read a book and learned that there are three types of schoolyard bullying. In the middle of your speech, you talk about those three types of bullying. If you do not tell your audience where you found that information, you are plagiarizing.

- The third trap that speakers fall into is re-citing someone else’s sources within a speech. To explain this problem, let’s look at a brief segment from a research paper written by Wrench, DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam:

“The main character on the hit Fox television show House, Dr. Gregory House, has one basic mantra, “It’s a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies. The only variable is about what” (Shore & Barclay, 2005). This notion that “everybody lies” is so persistent in the series that t-shirts have been printed with the slogan. Surprisingly, research has shown that most people do lie during interpersonal interactions to some degree. In a study conducted by Turner, Edgley, and Olmstead (1975), the researchers had 130 participants record their own conversations with others. After recording these conversations, the participants then examined the truthfulness of the statements within the interactions. Only 38.5% of the statements made during these interactions were labeled as “completely honest.”

In this example, we see that the authors of this paragraph cited information from two external sources: Shore and Barclay and Tummer, Edgley, and Olmstead. These two groups of authors are given credit for their ideas. The authors make it clear that they did not produce the television show House or conduct the study that found that only 38.5 percent of statements were completely honest. Instead, these authors cited information found in two other locations. This type of citation is appropriate.

However, if a speaker read the paragraph and said the following during a speech, it would be plagiarism:

“According to Wrench DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam, in a study of 130 participants, only 38.5 percent of the responses were completely honest.”

In this case, the speaker is attributing the information cited to the authors of the paragraph, which is not accurate. If you want to cite the information within your speech, you need to read the original article by Turner, Edgley, and Olmstead and cite that information yourself.

There are two main reasons we do this.

- First, Wrench, DiMartino, Ramirez, Oviedio, and Tesfamariam may have mistyped the information. Suppose the study by Turner, Edgley, and Olstead really actually found that 58.5 percent of the responses were completely honest. If you cited the revised number (38.5 percent) from the paragraph, you would be further spreading incorrect information.

- The second reason we do not re-cite someone else’s sources within our speeches is because it’s intellectually dishonest. You owe your listeners an honest description of where the facts you are relating came from, not just the name of an author who cited those facts. It is more work to trace the original source of a fact or statistic, but by doing that extra work you can avoid this plagiarism trap.

The Difference Between Global, Patchwork, and Incremental Plagiarism

This section is adapted from The Art of Public Speaking by Stephen E Lucas.

Global plagiarism: Stealing speech entirely from a single source and passing it off as your own. Maybe you go online and find a speech, or you use the speech your spouse created for her speech class. These are both examples of global plagiarism.

Patchwork plagiarism: Stealing ideas from two or more sources and passing them off as your own. You cut and paste information from one source, then another, then another and patch them together to make your speech, but you don’t cite each source within your speech.

Incremental plagiarism: Failing to give credit for particular parts of a speech that are borrowed from other people. In global and patchwork plagiarism, the entire speech is cribbed more or less verbatim from a single source or a few sources. But incremental plagiarism occurs when you borrow particular parts or increments from other people, quotes, or phrases to make your speech, and you don’t give credit. For example:

Whenever you quote someone directly, you must attribute the words to that person.

Scientist Roberts said, “Rocks also contain remnants of their electromagnetic information.”

Whenever you summarize or paraphrase someone else’s words or ideas you must attribute it to that person.

According to historian Belford, we are on the brink of a new era.

Now you have clearly identified Roberts and Belford and given them credit for their words, rather than presenting them as your own.

Ethically, we need to talk about your captive audience.

Captive Audiences

“Captive audience doctrine posits a situation in which the listener has no choice but to hear the undesired speech. This lack of choice has a strong spatial component to it: indeed, the classic example of a captive audience is being the target of residential picketing” (William, 2003, p. 400). For example, if picketers come to your neighborhood to picket the coming of a large store chain in a residential area, their speeches, yelling and propaganda can be heard in your home. They have entered your space and it doesn’t matter that you need quiet to put your little one down for a nap or you don’t agree with the picketer’s message, your are forced to listen because they are in your space.

“Defenders of sexual harassment law argue that employees’ need to earn a living makes the workplace a context where an employee should not be forced to listen to undesired speech” (William, 2003, p.404).

“In the case of the internet, it could be argued that the inability to filter out undesirable speech creates an unacceptable dilemma for a would-be user: use the internet and subject yourself to the risk of encountering such speech, or abstain altogether from using the medium (William, 2003, p. 404).

If we take this captive audience idea to our classroom, how does it apply? We are asking you to listen to at least two of your fellow students’ speeches as part of your grade. You don’t know if you will hear something offensive or something you don’t want to hear.

Knowing that others are required to hear your speech, implies that you are responsible for creating a speech that takes your “captive audience” into account and that you do not abuse the privilege. What does this mean to you when preparing a speech?

Topic Choice

Does this mean you cannot choose a controversial topic? You may choose a controversial topic. We will walk you through how to do that and still respect your audience.

Word Choice

Does this mean you can choose any words you want? Gone are the days when “sticks and stone could break our bones but words could never hurt us.” Words carry meaning and the ability to harm and alienate our audience. We will walk you through how to compose your speech to draw your audience in so they will want to hear more.

Visual Aids

Does this mean you can choose any visual aids you want? Visual images can be powerful ways to communicate your meaning if chosen well. They can also be damaging if not chosen well. We will walk you through how to choose your visual aids.

Gestures and Non-Verbal Delivery

Does this mean you can use any non-verbal delivery you want? More than 75 percent of our communication is non-verbal. It has a powerful effect on our audience. We will help you choose your non-verbal delivery so it will enhance your speech.

Captive Audience Outside of Class

Does this mean that you can speak to a captive audience any way you want outside of class? Outside of class, speakers still have a responsibility to respect their captive-audience privilege and to speak and use it ethically. We’ll talk about how.

The First Amendment and Free Speech

Some speakers feel that they can talk about anything they want, to anyone they want, in anyway they want because their speech is protected under the First Amendment, allowing them to behave in the following ways:

- Be foul mouthed.

- Use destructive topics.

- Use naked visual aids.

- Tell their audience how much they should despise their neighbors.

These speakers feel the First Amendment gives them the freedom of any kind of speech. Do you know if this is true?

Speech Covered Under the First Amendment

This section is adapted from The Art of Public Speaking by Stephen E Lucas.

Disputes over the meaning and scope of the First Amendment arise almost daily in connection with issues such as terrorism, pornography, and hate speech.

There are some kinds of speech that are not protected under the First Amendment, including the following:

- Defamatory falsehoods that destroy a person’s reputation.

- Threats against the life of the President.

- Inciting an audience to illegal action in circumstances where the audience is likely to carry out the action.

Otherwise, the Supreme Court has held—and most ethics communication experts have agreed—that public speakers have an almost unlimited right of free expression.

While free speech allows for much individual expression, you have learned that there are ethical guidelines for public speaking. But did you know there are ethical guidelines for listening as well?

It is surprising to see that adults, in a sedate context, set a poor example and forget their ethical listening manners. See if you can hear them in the video, GOP Rep. to Obama: “You lie!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sipHTEARyYo

GOP Rep to Obama You Lie!, by Communication 1020 Videso, Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sipHTEARyYo

There is a time for debate, disagreement, and protest. However, ethical listening takes into account the following:

- What is appropriate for the context.

- The implications of an outburst.

Lucas gives us clear information about ethical listening in his list.

Guidelines for Ethical Listening

- Be courteous and attentive. The speaker has put a lot of work into the speech. It is surprising how often student audience members think it is ok to look at their phones, newspapers, work on homework, or even leave the room during a speech. These are all unethical listening behaviors and should be avoided.

- Avoid prejudging the speaker. It is easy to see what a speaker is wearing, their accent, or even word choice and to prejudge their message. This doesn’t mean you need to agree with everything a speaker has to say, but you might be surprised what you will learn if you attentively listen to the full speech with an open mind.

- Maintain the free and open expression of ideas. Just as the speaker needs to avoid name-calling and tactics that shut down free speech, listeners have an obligation to maintain the speaker’s right to be heard. You don’t need to agree with the speaker.

References

Lucas, S.E. (2014). The Art of Public Speaking (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

University of Minnesota. (2011). Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/. CC BY-SA 4.0.

William, D. A. (2003). Captive audiences, children and the internet. Brandeis Law Journal 41, 397-415

Media References

(no date). yell, shout, scream, anger, angry, mouth, person, human body part, body part, close-up [Image]. pxfuel. https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-odgkm

A K M Adam. (2018, 28 February). Picketers, Exam Schools [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/akma/39950320734/

Bruce Mars. (no date). Woman Thinking Photo [Image]. StockSnap. https://stocksnap.io/photo/woman-thinking-MLZIHL9GLY

Caragiuss. (2013, 29 January). Ballroom dance [Image]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ballroom_dance.jpg

Carmella Fernando. (2007, 24 September). Promise? [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/13923263@N07/1471150324/

Communication 1020 Videso. (2021, November 9). GOP Rep to Obama You Lie! Source [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sipHTEARyYo

OpenClipart-Vectors. (2016, March 31). Angel Chess Demon [Image]. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/vectors/angel-chess-demon-devil-evil-game-1294401/

Presidio of Monterey. (2014, 26 April). DLIFLC students compete in 39th Annual Mandarin Speech Contest in San Francisco [Image]. flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/presidioofmonterey/13890165109

Sulogocreativocom. (2017, 15 September). Coca cola ejemplo logo [Image]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coca_cola_ejemplo_logo.png

Tilley, E. (2005). The ethics pyramid: Making ethics unavoidable in the public relations process. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 20, 305–320. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/2-1-the-ethics-pyramid/#wrench_1.0-ch02_s01_f01