Chapter 18: Persuasive Speaking

This chapter is adapted from Chapter 17 of Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 and Chapter 13 of Exploring Public Speaking: 4th Edition, by Kristin Barton, Amy Burger, Jerry Drye, Cathy Hunsicker, Amy Mendes and Matthew LeHew, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

What are the theories of Persuasion?

Persuasion Introduced: Theories of Persuasion

Persuasion Today

In his text, The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the 21st Century, Richard Perloff notes that studying persuasion today is extremely important for five basic reasons:

- Persuasive communications have grown exponentially in sheer numbers.

- Persuasive messages travel faster than ever before.

- Persuasion has become institutionalized.

- Persuasive communication has become more subtle and devious.

- Persuasive communication is more complex than ever before (Perloff, 2003).

In essence, persuasive communication’s nature has changed over the last fifty years due to the influx of various technology types. People are bombarded by persuasive messages in today’s world, so thinking about how to create persuasive messages effectively is very important for modern public speakers. A century, or even half a century ago, public speakers contended only with printed words on paper for attracting and holding an audience’s attention. Today, public speakers must contend with laptops, netbooks, iPads, smartphones, smartboards, television sets, and many other tools to send various persuasive messages immediately to a target audience.

Defining Persuasion

Persuasion is an attempt to get a person to behave in a manner or to embrace a viewpoint related to values, attitudes, and beliefs that he or she would not do otherwise. If you think this describes your informative speech, you are partially right. Think of it like this: information + persuasion = change.

Change a View Point: Attitudes, Values, and Beliefs

The first persuasive public speaking type involves changing someone’s attitudes, values, and beliefs. An attitude is defined as an individual’s general predisposition toward something as being good or bad, right or wrong, or negative or positive. Maybe you believe that local curfew laws for people under twenty-one are a bad idea, so you want to persuade others to adopt a negative attitude toward such laws.

You can also attempt to persuade individuals to change their value toward something. Value refers to an individual’s perception of something’s usefulness, importance, or worth. We can value a college education or technology or freedom. Values, as a general concept, are fairly ambiguous and tend to be very lofty ideas. Ultimately, what we value in life actually motivates us to engage in various behaviors. For example, if you value technology, you are more likely to seek out new technology or software on your own. On the contrary, if you do not value technology, you are less likely to seek out new technology or software unless someone or some circumstance requires you to.

Lastly, you can attempt to persuade people to change their personal beliefs. Beliefs are propositions or positions that an individual holds as true or false without positive knowledge or proof. Typically, beliefs are divided into two basic categories: core and dispositional. Core beliefs are beliefs that people have actively engaged in and created throughout their lives, for example, a belief in a higher power or a belief in extraterrestrial life forms. Dispositional beliefs, on the other hand, are beliefs that people have not actively engaged in and created, but rather judgments that they make based on their related subject knowledge when they encounter a proposition. For example, imagine that you are asked the question, “Can stock cars reach speeds of one thousand miles per hour on a one-mile oval track?” Even though you may never have attended a stock car race or even seen one on television, you can make split-second judgments about your automobile-speed understanding and say fairly certainly that you believe stock cars cannot travel at one thousand miles per hour on a one-mile track.

When it comes to persuading people to alter core and dispositional beliefs, persuading audiences to change core beliefs is more difficult than persuading them to change dispositional beliefs. For this reason, you are very unlikely to persuade people to change their deeply held core beliefs about a topic in a five- to seven-minute speech. However, if you give a persuasive speech on a topic related to an audience’s dispositional belief, you may have better success. While core beliefs may seem to be exciting and interesting, persuasive topics related to dispositional beliefs are generally better for novice speakers with limited time allotments.

Change Behavior

The second type of persuasive speech is one in which the speaker attempts to persuade an audience to change their behavior. Behaviors come in various forms, so finding one you think people should start, increase, or decrease shouldn’t be difficult at all. Speeches encouraging audiences to vote for a candidate, sign a petition opposing a tuition increase, or drink tap water instead of bottled water are all behavior-oriented persuasive speeches. In all these cases, the goal is to change an individual listener’s behavior.

Persuasion Theories

Understanding how people are persuaded is very important to a public speaking discussion. Thankfully, many researchers have created theories that help explain why people are persuaded. While there are numerous theories, we are only going to examine three: social judgment theory, cognitive dissonance theory, and the elaboration likelihood model.

Social Judgment Theory

Social judgment theory asks that you think of persuasion as a continuum or line going both directions. Your audience members, either as a group or individually, are sitting somewhere on that line in reference to your thesis statement—your proposition. Also, the word “claim” is used for a proposition or thesis statement in a persuasive speech because you are claiming an idea is true or an action is valuable, which the audience may not find true or acceptable. To be an effective persuasive speaker, after determining your topic, determine where your audience “sits” on the continuum.

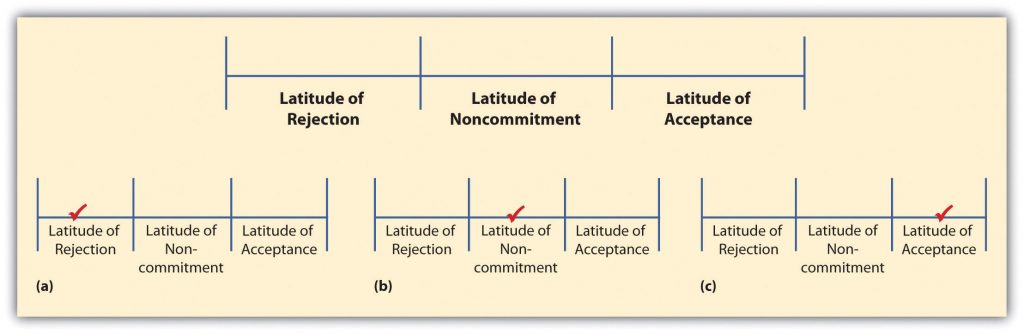

Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland created social judgment theory to determine what message types and under what conditions communicated messages lead to changing someone’s behavior (Sherif & Hovland, 1961). In essence, they found that people’s perceptions of attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors exist on a continuum that they call latitude of rejection, latitude of noncommitment, and latitude of acceptance (Figure 17.2 “Latitudes of Judgments”).

Sherif and Hovland theorized that persuasion is a matter of knowing how great the discrepancy or difference is between the speaker and the audience’s viewpoint. If the speaker’s viewpoint is similar to audience members’ viewpoint, then persuasion is more likely. If the discrepancy between the two is too great, then persuasion decreases dramatically.

To describe this theory in more detail, imagine that you plan to persuade your peers to major in a foreign language. Some peers will disagree with you right off the bat, which is latitude of rejection, part (a). Other peers will think majoring in a foreign language is a great idea: latitude of acceptance, part (c). Still others will have no opinion either way: latitude of noncommitment, part (b). Now, in each latitude there is a range of possibilities. For example, one listener may accept the idea of minoring in a foreign language, but when asked to major or even double major in a foreign language, he or she ends up in the latitude of noncommitment or even rejection.

Persuasive messages are the most likely to succeed when they fall into an individual’s latitude of acceptance. For example, people who are in favor of majoring in a foreign language are more likely to positively evaluate your message, assimilate your advice into their own ideas, and engage in desired behavior. On the other hand, people who reject your message are more likely to negatively evaluate your message, not assimilate your advice, and not engage in desired behavior.

We often find ourselves in situations where we are trying to persuade others to change attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors with which they may not agree, so think about the range that exists. For example, in our foreign language case, see the following possible opinions from the audience’s perspective:

- Complete agreement: Let’s all major in foreign languages.

- Strong agreement: I will major in a foreign language; I will double major in a foreign language.

- Agreement in part: I won’t major in a foreign language, but I will minor in a foreign language.

- Neutral: While I think studying a foreign language can be worthwhile, I also think a college education can be complete without it. I really don’t feel strongly one way or the other.

- Disagreement in part: I will only take the foreign language classes required by my major.

- Strong disagreement: I don’t think I should have to take any foreign language classes.

- Complete disagreement: Majoring in a foreign language is a complete waste of a college education.

These seven possible opinions on the subject do not represent the full spectrum of choices, but give us various degrees of agreement with the general topic.

Sherif and Hovland theorized that persuasion was a matter of knowing how great the discrepancy or difference was between the speaker’s viewpoint and that of the audience. If the speaker’s point of view was similar to that of audience members, then persuasion was more likely. If the discrepancy between the idea proposed by the speaker and the audience’s viewpoint is too great, then the likelihood of persuasion decreases dramatically.

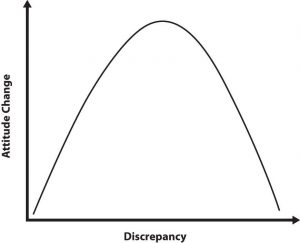

Sherif and Hovland also suggest that there is a threshold for most people where attitude change isn’t possible. These people slip from the latitude of acceptance into the latitude of noncommitment or rejection. The “Discrepancy and Attitude Change” graph represents this process. The area covered by the curve’s left side represents options a person agrees with, even if there is an initial discrepancy between the speaker and audience member at the speech’s start. However, there comes a point where the discrepancy between the speaker and audience member becomes too large, which moves into the options that the audience member automatically rejects. In essence, it’s essential for you to know with which options you can realistically persuade your audience and which options will never happen. Maybe there is no way for you to persuade your audience to major or double major in a foreign language, but perhaps you can get them to minor in a foreign language. While you may not be achieving your complete end-goal, it’s better than getting nowhere at all. This is called baby steps—we want to bring the audience as close as we can to our persuasive goal without moving them into the disagree category.

Those who disagree with your proposition but are willing to listen are called the target audience. These are the audience members you want to target to persuade. At the same time, another audience cluster are those who are extremely opposed to your position to the point that they probably will not give you a fair hearing. Finally, some audience members may already agree with you, although they don’t know why.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory

Why is persuasion hard? Persuasion is hard mainly because we have a bias against change. As much as we hear statements such as, “The only constant is change” or “Variety is the spice of life,” research evidence shows that in reality, people do not like change. For example, recent risk-aversion research points to how we are more concerned about not losing something than about gaining something. Change is often seen as a loss rather than a gain, or a gamble, or a step into the unknown (Vedantam & Greene, 2013).

Additionally, psychologists point to how we protect our beliefs, attitudes, and values by selectively exposing ourselves to messages that we already agree with, rather than those that confront or challenge us. This selective exposure is especially evident in an individual’s mass media choices, such as which TV, radio, podcast, or Internet sites they chose to listen to and read. Not only do we selectively expose ourselves to information, we selectively attend to, perceive, and recall information that supports our existing viewpoints. These behaviors are referred to as selective attention, selective perception, and selective recall.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory arose from the selective exposure notion. In 1957, Leon Festinger proposed a theory for understanding how persuasion functions, called cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957). Cognitive dissonance is an aversive motivational state that occurs when an individual entertains two or more contradictory attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors simultaneously. For example, maybe you know you should be working on your speech, but you really want to go to a movie with a friend. In this case, practicing your speech and going to the movie are two cognitions that are inconsistent with one another. To successfully persuade your audience, you must induce enough cognitive dissonance in listeners so that they will change their attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors.

For cognitive dissonance to work effectively there are three necessary conditions: aversive consequences, freedom of choice, and insufficient external justification (Frymier & Nadler, 2007). Aversive consequence means there is strong enough punishment for not changing one’s attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors. For example, you give a speech on why people need to eat more apples. If your aversive consequence for not eating apples is that your audience will not get enough fiber, most people will simply not be persuaded because the punishment isn’t severe enough. Instead, the punishment associated with not eating apples needs to be significant enough to change their behavior. If you convince your audience that without enough fiber in their diets they are at higher risk for heart disease or colon cancer, they might fear the aversive consequences enough to change their behavior.

Freedom of choice, the second condition necessary for cognitive dissonance to work, means that people must feel they have the freedom to make their own choice. If listeners feel they are being coerced into doing something, then dissonance will not be aroused. They may alter their behavior in the short term, but as soon as the coercion is gone, the original behavior will reemerge. It’s like the person who drives more slowly when a police officer is nearby but ignores speed limits once officers are no longer present. As a speaker, if you want to increase cognitive dissonance, make sure that your audience doesn’t feel coerced or manipulated, but rather that they can clearly see that they have a choice to be persuaded.

External and internal justifications are the final condition necessary for cognitive dissonance to work. External justification refers to identifying reasons outside of one’s own control to support one’s behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. Internal justification refers to someone voluntarily changing a behavior, belief, or attitude to reduce cognitive dissonance. When it comes to creating change through persuasion, external justifications are less likely to produce change than internal justifications (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959).

For example, you give a speech with the specific purpose to persuade college students to use condoms whenever they engage in sexual intercourse. Your anonymous survey audience analysis indicates that many listeners do not consistently use condoms. Which is the more persuasive argument: (a) “Failure to use condoms inevitably results in unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including AIDS,”or (b) “If you think of yourself as a responsible adult, you’ll use condoms to protect yourself and your partner”? With the first argument, you have provided external justification for using condoms, such as the terrible things that will happen if you don’t use condoms. Listeners who reject this external justification because they don’t believe these dire consequences are inevitable are unlikely to change their behavior. With the second argument, however, if your listeners think of themselves as responsible adults, and they don’t consistently use condoms, the conflict between their self-image and their behavior elicits cognitive dissonance. To reduce this cognitive dissonance, they are likely to seek internal justification because they want to view themselves as responsible adults and change their behavior by using condoms more consistently. In this case, according to cognitive dissonance theory, the second persuasive argument—internal justification—is the one more likely to lead to a behavior change.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

The elaboration likelihood model, created by Petty and Cacioppo (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), is the last of the three persuasion theories discussed here. The basic model has a continuum from high elaboration or thought to low elaboration or thought. Petty and Cacioppo refer to the term elaboration as the amount of thought or cognitive energy someone uses to analyze a message’s content. High elaboration uses the central route and is designed for analyzing a message’s content. As such, when people truly analyze a message, they use cognitive energy to examine the arguments set forth within the message. In an ideal world, everyone processes information through this central route and actually analyzes arguments presented to them. Unfortunately, many people often use the peripheral route when processing persuasive messages, which results in low elaboration or thought. Low elaboration occurs when people attend to messages but do not analyze the message or use cognitive energy to ascertain the message’s arguments.

For persuasion researchers, the question then becomes how do people select one route or the other when attending to persuasive messages? Petty and Cacioppo noted that there are two basic factors that determine whether someone centrally processes a persuasive message: ability and motivation. Ability means that audience members must be able to process the persuasive message. If the language or message is too complicated, then people will not highly elaborate on it because they will not understand the persuasive message. Motivation, on the other hand, refers to whether the audience member chooses to elaborate on the message.

Frymier and Nadler discussed five basic factors that can lead to high elaboration: personal relevance and personal involvement, accountability, personal responsibility, incongruent information, and need for cognition (Frymier & Nadler, 2007).

Personal Relevance and Personal Involvement

Personal relevance and personal involvement are the first reason people are motivated to take the central route or to use high elaboration when listening to a persuasive message. Personal relevance refers to whether the audience member feels that he or she is actually directly affected by the speech topic. For example, if someone is listening to a speech on why cigarette smoking is harmful, and that listener has never smoked cigarettes, he or she may think the speech topic simply isn’t relevant. Obviously, as a speaker, always think about how your topic is relevant to your listeners and make sure to drive this home throughout your speech. Personal involvement, on the other hand, asks whether the individual is actively engaged with the issue at hand. For example, does the listener send letters of support, give speeches on the topic, have a bumper sticker, and so forth. If an audience member is an advocate who is constantly denouncing tobacco companies for their harm to society, then he or she is highly involved and engages in high elaboration during a persuasive speech about cigarette smoking’s harmfulness.

Accountability

Accountability, the second condition under which people are likely to process information using the central route, occurs when they feel that they will be held accountable for the information after the fact. With accountability, there is the perception that someone or a group of people will be watching to see if the receiver remembers the information later on. We’ve all witnessed this phenomenon when one student asks the question, “Will this be on the test?” If the teacher says, “No,” you can almost immediately see students’ eyes glaze over as they tune out the information. As a speaker, it’s often hard to hold your audience accountable for the information given within a speech.

Personal Responsibility

Personal responsibility refers to when people feel that they are going to be held responsible for evaluating a message or for a message’s outcome. If this is the case, and if there is not a clear external accounting involved, listeners are more likely to critically think through the message using the central route. For example, you’ve been asked to evaluate your public speaking peers. Research shows that if only one or two students are asked to evaluate any one speaker at a time, the speaker evaluations are better quality than if everyone in the class is asked to evaluate every speaker. When people feel that their evaluation is important, they take more responsibility and are more critical of the message.

Incongruent Information

Incongruent information refers to how people are motivated to centrally process information when it does not adhere to their own ideas. For example, you’re a highly progressive liberal, and one of your peers delivers a speech on the Tea Party movement’s importance in American politics. The information presented during the speech will most likely be in direct contrast to your personal ideology, which causes incongruence because the Tea Party ideology is opposed to a progressive liberal ideology. As such, you are more likely to pay attention to the speech, specifically looking for flaws in the speaker’s argument.

Need-for-Cognition

Need-for-cognition refers to some people who centrally process information because of a personality characteristic. Need-for-cognition refers to a personality trait characterized by an individual’s internal drive or need to engage in critical thinking and information processing. People who are high in need-for-cognition simply enjoy thinking about complex ideas and issues. Even if the idea or issue being presented has no personal relevance, high need-for-cognition people are more likely to process information using the central route.

What are the types of persuasive claims?

Obviously, there are many different, interesting persuasive claims or speech topics to select for a public speaking class. For instance, to change a specific college or university policy, or to increase U.S. enforcement against trafficking women and children. Notice in the first sentence that we used the word claims to refer to speech topics. This is because when we attempt to persuade others, we are making a claim, and we use evidence and logic to support our claim. Below, we discuss three common claim types used to persuade: factual claims, policy claims, and value claims.

Factual Claims

Factual claims set out to argue an assertion’s truth or falsity. Some factual claims are simple to answer: Barack Obama is the first African American President; Robert Wadlow, the tallest man in the world, was eight feet and eleven inches tall; Facebook wasn’t profitable until 2009. All these factual claims are well documented by evidence and can be easily supported with a little research.

However, many factual claims cannot be answered absolutely. For some factual claims it is hard to determine whether they are true or false because the final answer on the subject has not yet been discovered. For example, when is censorship good? What rights should animals have? When does life begin? Probably the most historically interesting and consistent factual claim is whether a higher power, God, or other religious deity exists. The issue is that there is not enough evidence to clearly answer this factual claim in any specific direction, which is where the concept of faith must be involved.

Predictions, which may or may not happen, are other factual claims that may not be easily answered using evidence. For example, you give a speech on climate change’s future or U.S. terrorism’s future. While there may be evidence that something possibly will happen in the future, unless you’re a psychic, you don’t actually know.

When thinking about factual claims, pretend that you’re putting a specific claim on trial, and as the speaker, your job is to defend your claim as a lawyer would defend a client. Ultimately, your job is to be more persuasive than your audience members, who act as both opposition attorneys and judges.

Policy Claims

Policy claims make a statement about a problem and offer the solution to implement. Policy claims are probably the most common persuasive speaking form because we live in a society surrounded by problems and people who have ideas about how to fix these problems. Let’s look at a few possible policy claims examples:

- The United States should end capital punishment.

- Human cloning for organ donations should be legal.

- Nonviolent drug offenders should be sent to rehabilitation centers and not prisons.

- The United States needs to invest more in preventing poverty at home and less in feeding starving people around the world.

Each policy claim has a clear perspective for which to advocate: they always present a clear and direct opinion about what should occur and what needs to change. When presenting policy claims, there are two different persuasive goals to examine: to gain passive agreement and to gain immediate action.

To Gain Passive Agreement

To gain passive agreement means to persuade your audience to agree with what you are saying about a specific policy without asking them to do anything to enact the policy. For example, you speak on why the Federal Communications Commission should regulate violence on television like it does foul language, and you advocate for no violence on TV until after 9 pm. Your goal is to get your audience to agree that it is in our best interest as a society to prevent violence from being shown on television before 9 pm, but, you are not seeking to have your audience run out and call their senators or congressmen or even sign a petition. Often, the first step in larger political change is simply getting a massive number of people to agree with your policy perspective.

Let’s look at a few more passive agreement claims:

- Racially profiling individuals suspected of belonging to known terrorist groups is a way to make America safer.

- Colleges and universities should voluntarily implement a standardized testing program to ensure student learning outcomes are similar across different institutions.

In each of these claims, the goal is to sway one’s audience to a specific attitude, value, or belief, but not necessarily to get the audience to enact any specific behaviors.

To Gain Immediate Action

To gain immediate action means to persuade your audience to start engaging in a specific behavior. This is the alternative to gain passive agreement. Many passive agreement topics can become immediate action-oriented topics as soon as you tell your audience what behavior to engage in, such as to sign a petition, to call a senator, or to vote. While it is much easier to gain passive agreement than to get people to do something, always try to get your audience to act and do so quickly. A common mistake that speakers make is telling people to enact a behavior that will occur in the future. The longer it takes for people to engage in the action you desire, the less likely it is that your audience will engage in that behavior.

Here are some examples of good claims with immediate calls-to-action:

- College students should eat more fruit, so I am encouraging everyone to eat the apple I have provided you and start getting more fruit in your diet.

- Teaching a child to read is one way to ensure that the next generation will be more literate than those who have come before us, so please sign up right now to volunteer one hour a week to help teach a child to read.

Each example starts with a basic claim and then tags on an immediate call-to-action. Remember, the faster you can get people to engage in a behavior, the more likely they actually will.

Value Claims

Value claims advocate making a judgment about something. For example, it’s good or bad, it’s right or wrong, it’s beautiful or ugly, moral or immoral.

Let’s look at three value claims. We’ve italicized the evaluative term in each claim:

- Dating people on the Internet is an immoral dating practice.

- It’s unfair for pregnant women to have special parking spaces at malls, shopping centers, and stores.

Each value claim could be made by a speaker, and other speakers could say the exact opposite. When making a value claim, it’s hard to ascertain why someone has chosen a specific value stance without understanding her or his criteria for making the evaluative statement. For example, if someone finds all forms of technology immoral, then it’s really no surprise that he or she would find Internet dating immoral as well. As such, you must clearly explain your criteria for making the evaluative statement. Ultimately, when making a value claim, make sure that you clearly label your evaluative term and provide clear criteria for how you came to your evaluation.

What is reasoning and what are errors in reasoning?

Recall that in previous chapters, we discussed the three rhetorical appeals known as ethos, pathos, and logos. In this chapter, we discuss the second part of logos, or logical argument, which includes using critical thinking to fashion and evaluate persuasive appeals. When giving a persuasive speech, in addition to providing fresh evidence, present your audience with a logical speech and arguments that they understand and to which they can relate. Logos involves composing a speech that is logically structured and easy-to-follow. Logos also involves using correct logical reasoning and avoids using fallacious reasoning, or logical fallacies.

First, let’s start by thinking about critical thinking, which is a term with many meanings. One meaning is the traditional ability to use formal logic. To do so, you must first understand the two reasoning types: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning, also called induction, is probably the reasoning form we use more regularly. Induction is sometimes referred to as “reasoning from example or specific instance,” and indeed, that is a good description. Induction is also referred to as “bottom-up” thinking. And inductive reasoning is sometimes called “the scientific method.” Inductive reasoning happens when we look around at various happenings, objects, behavior, etc., and see patterns. From those patterns, we develop conclusions.

There are four inductive reasoning types that we discuss below: generalization, causal reasoning, sign reasoning, and analogical reasoning. Each is based on different evidence and logical moves or jumps.

Generalization is a form of inductive reasoning that draws conclusions based on recurring patterns or repeated observations. One must observe multiple instances and find common qualities or behaviors and then make a broad or universal statement about them. For example: if every dog I see chases squirrels, then I would probably generalize that all dogs chase squirrels. Another example: if you are a coffee drinker, you might hear news reports about coffee being bad for your health, and then six months later, another study shows that coffee has positive health effects. Scientific studies are often repeated or conducted in different ways to obtain more and better evidence and to make updated conclusions. Consequently, the way to disprove inductive reasoning is to provide contradictory evidence or examples.

Causal Reasoning seeks to make cause-effect connections instead of looking for patterns the way generalization does. Causal reasoning is a form of inductive reasoning, and we use it all the time without even thinking about it. For example: if the street is wet in the morning, you know that it rained based on past experience. Of course, there could be another cause—the city decided to wash the streets early that morning—but your first conclusion would be rain.

Sign Reasoning is a form of inductive reasoning in which conclusions are drawn about phenomena based on events that precede or co-exist with, but not cause, a subsequent event. Signs are like the correlation mentioned above under causal reasoning. For example: someone argues, “In the summer, more people eat ice cream. And in the summer, there is statistically more crime. Therefore, eating more ice cream causes more crime!” Or, “More crime makes people eat more ice cream.” That, of course, would be silly. Ice cream and crime are two things that happen at the same time—signs—but they are effects of something else—hot weather. If we see one sign, we will see the other. Either way, they are signs or perhaps two different things that just happen to be occurring at the same time, but not causes.

Analogical Reasoning involves comparison. For it to be valid, the two things being compared—schools, states, countries, businesses—must be essentially truly alike in many important ways. For example, although Harvard University and your college are both higher education institutions, they are not essentially alike in very many ways. They may have different missions, histories, governance, surrounding locations, sizes, clientele, stakeholders, funding sources, funding amounts, etc. So, it is foolish to argue, “Harvard has a law school; therefore, since we are both colleges, my college should have a law school, too.” On the other hand, there are colleges that are very similar to your college in all those ways, so comparisons could be valid in those cases.

A popular argument structure that comes from informal logic or inductive reasoning is the Toulmin Model.

For more information see the Toulmin Argument from the OWL at Purdue.

Deductive

Deductive reasoning, or deduction, is a reasoning type in which a conclusion is based on the combination of multiple premises that are generally assumed to be true. It has been referred to as “reasoning from principle,” which is a good description. It can also be called “top-down” reasoning. First, formal deductive reasoning employs the syllogism, which is a three-sentence argument composed of a major premise—a generalization or principle that is accepted as true; a minor premise—an example of the major premise; and a conclusion. This conclusion has to be true if the major and minor premise are true.

For example: All men are mortal.

- Major premise: something everyone already agrees on. Socrates is a man.

- Minor premise: an example taken from the major premise. Socrates is mortal.

- Conclusion: the only conclusion that can be drawn from the first two sentences. All men are mortal.

In this reasoning type, see how easy it is to create a reasoning error. Look at the following example, and pick out the reasoning error or logical fallacy.

- Major Premise: Nobody’s perfect.

- Minor Premise: I’m nobody.

- Conclusion: I’m perfect.

Deductive reasoning helps us go from known to unknown and can lead to reliable conclusions if the premises and the method are correct. It has been around since the ancient Greeks. It is not the flipside of inductive but a separate logic method. While enthymemes—an argument in which one premise is not explicitly stated—are not always errors, listen carefully to arguments that use them to be sure that something incorrect is not being assumed or presented.

Reasoning Errors: Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are reasoning mistakes, which happen when you get one of the formulas wrong, such as inductive or deductive. There are actually dozens upon dozens of fallacies. To achieve a logical speech, avoid logical fallacies. The Owl at Purdue offers explanations of some of the most common ones to know to avoid poor speech logic and to become a better critical thinker.

Logical Fallacies – The Owl at Purdue

As you know now, it is a good idea to understand logical fallacies so that you don’t use them in your own persuasive speech and so that you become a better critical information consumer when someone is trying to persuade you!

Adapted from “Chapter 14: Logical Reasoning,” by Tucker, B., Barton, K., Burger, A., Drye, J., Hunsicker, C., Mendes, A., & LeHew, M., In Exploring Public Speaking (4th ed., pp. 286–304). 2019, Communication Open Textbooks. Creative Commons.

References

Barton, K., Tucker, B.G. (2016). Exploring Public Speaking 4th Edition. University System of Georgia. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/communication-textbooks/1/. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

University of Minnesota. (2011). Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Media References

Burns Library, Boston College. (2020, October 16). Maya Angelou [Image]. Le Sabre. https://thelesabre.com/49508/uncategorized/maya-angelou/

Unknown. (2011). Discrepancy and attitude change [Image]. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, University of Minnesota. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/17-1-persuasion-an-overview/

Unknown. (2011). Latitudes of judgments diagram [Image]. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, University of Minnesota. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/17-1-persuasion-an-overview/

PBS NewsHour. (2008, September 4). Podium [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/newshour/2828110801/