Chapter 1: Foundations of Public Speaking

This chapter is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

What are examples of public speaking in real life?

You may not think you will use public speaking very much, but the top two richest men in the world think you will. Do you know who these men are?

When college students like you asked these two richest men what the number-one skill they felt was important for employees in their company, guess what they answered? Read and find out.

Warren Buffett: Developing this skill can make ‘a major difference in your future earning power’

So, this class is going to teach you a skill that will last you a lifetime.

Because we live in a world where we are overwhelmed with content, communicating information in a way that is accessible to others is more important today than ever before. Every day people across the United States and around the world present to an audience and speak. In fact, a monthly publication called Vital Speeches of the Day reproduces some of the top speeches from around the United States.

Personal Benefits of Public Speaking

Oral communication skills are the number-one skill that college graduates found useful in business, according to a study by sociologist Andrew Zekeri (Zekeri, 2004). Some benefits include the following:

- Developing critical thinking skills.

- Fine-tuning verbal and nonverbal skills.

- Overcoming fear of public speaking. Developing Critical Thinking Skills

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

One critical thinking skill you will hone during this course is problem solving. For example, when preparing a persuasive speech, you’ll have to think through real problems affecting your campus, community, or the world and provide possible solutions to those problems. You’ll also have to think about your solution’s positive and negative consequences and then communicate your ideas to others. At first, it may seem easy to find solutions for a campus problem. For example, for few parking spaces, just build more spaces. But after thinking and researching further, you may find that building costs, environmental impact from losing green space, maintenance needs, or limited locations for additional spaces make this solution impractical. Thinking through problems and analyzing your solution’s potential costs and benefits is essential to critical thinking and persuasive public speaking. And these skills will help you not only in public speaking contexts but throughout your life as well.

Fine-Tuning Verbal and Nonverbal Skills

Whether you’ve competed in high school public speaking or this is your first time speaking in front of an audience, having the opportunity to actively practice communication skills and receive professional feedback will help you become a better overall communicator. Often, people don’t realize that they twirl their hair or repeatedly mispronounce words while speaking in public settings until they receive feedback from a teacher during a public speaking course. Many United States presenters often pay speech coaches over one hundred dollars per hour to help them enhance their speaking skills. You have a built-in speech coach right in your classroom, so use this opportunity to your advantage to improve your verbal and nonverbal communication skills.

Overcoming Fear of Public Speaking

Whether they’ve spoken in public often or are just getting started, most people experience some anxiety when publicly speaking. Professors Heidi Rose and Andrew Rancer evaluated students’ public speaking anxiety levels during their public speaking classes’ first and last weeks and found that anxiety levels decreased over the semester (Rose & Rancer, 1993). One explanation is that people often have little exposure to public speaking. By taking a public speaking course, you become better acquainted with the public speaking process, making you more confident and less apprehensive. In addition, you will learn specific strategies for overcoming speech-anxiety challenges.

Influencing the World around You

If you don’t like something about your local government, then speak out about your issue! One of the best ways to get our society to change is through the power of speech. Common citizens like you fare influencing the world in real ways through powerful speech. Just type the words “citizens speak out” in a search engine, and you’ll find numerous examples of how common citizens use the power of speech to make real changes in the world. For example, people speak out against “fracking” for natural gas—a process in which chemicals are injected into rocks to open them up for fast natural gas or oil flow—or to favor retaining a popular local sheriff. One of the amazing gifts a citizen in a democracy can exercise is the right to stand up and speak out, which is a luxury many people in the world do not have. So, if you don’t like something, be the force of change you seek through the power of speech.

Developing Leadership Skills

Have you ever thought about climbing the corporate ladder and eventually finding yourself in a management or other leadership position? If so, then public speaking skills are essential. Hackman and Johnson assert that effective public speaking skills are a necessity for all leaders (Hackman & Johnson, 2004). If you want to lead, you have to communicate to followers effectively and clearly. According to Bender, “Powerful leadership comes from knowing what matters to you. Powerful presentations come from expressing this effectively. It’s important to develop both” (Bender, 1998). One of the most important skills for leaders to develop is their public speaking skills, which is why executives spend millions of dollars every year going to public speaking workshops, hiring public speaking coaches, and buying public speaking books, CDs, and DVDs.

Becoming a Thought Leader

Even if you are not in an official leadership position, effective public speaking can help you become a “thought leader.” Joel Kurtzman, editor of Strategy & Business, coined this term to call attention to individuals who contribute new ideas to the business world. According to business consultant Ken Lizotte, “when your colleagues, prospects, and customers view you as one very smart guy or gal to know, then you’re a thought leader” (Lizotte, 2008). Typically, thought leaders’ behaviors include enacting and conducting business practices research. To achieve thought leader status, individuals must communicate their ideas to others through both writing and public speaking. Lizotte demonstrates how becoming a thought leader can be both personally and financially rewarding: “when others look to you as a thought leader, you will be more desired and make more money as a result.” Business gurus often refer to a person’s “intellectual capital”—the combination knowledge and your ability to communicate that knowledge to others (Lizotte, 2008).

What are the steps of the speechmaking process?

Now that we know that public speaking is an important part of life, how do we do it? What are speech-building foundations?

All speeches fall within three basic categories: informative, persuasive, and entertaining. You will be giving an informative and persuasive speech later in the semester.

Informative Speaking

The primary purpose of informative presentations is to share one’s knowledge of a subject with an audience.

For example,

- You might be asked to instruct a group of coworkers on how to use new computer software or to report to a group of managers how your latest project is coming along.

- A local community group might wish to hear about your volunteer activities in New Orleans during spring break, or your classmates may want you to share your expertise on Mediterranean cooking.

- Teachers find themselves presenting to parents as well as to their students.

- Firefighters give demonstrations about how to effectively control a fire in the house.

Informative speaking is a common part of numerous jobs and other everyday activities. As a result, learning how to speak effectively has become an essential skill in today’s world.

Persuasive Speaking

We are often called on to convince, motivate, or otherwise persuade others to change their beliefs, take an action, or reconsider a decision.

- Advocating for music education in your local school district.

- Convincing clients to purchase your company’s products.

- Inspiring high school students to attend college all involve influencing other people through public speaking.

- For some people, such as elected officials, giving persuasive speeches is a crucial part of attaining and continuing career success.

- Other people make careers out of speaking to groups of people who pay to listen to them. Motivational authors and speakers, such as Les Brown, make millions of dollars each year from people who want to be motivated to do better in their lives.

- Brian Tracy, another professional speaker and author, specializes in helping business leaders become more productive and effective in the workplace.

If you develop the skill to persuade effectively, it can be personally and professionally rewarding.

Entertaining Speaking

Entertaining speaking involves an array of speaking occasions. Not all require a speaker to be funny as you will see in the list.

- Introductions.

- wedding toasts.

- presenting and accepting awards.

- delivering eulogies at funerals and memorial services.

- after-dinner speeches.

- motivational speeches.

As anyone who has watched an awards show on television or has seen an incoherent best man deliver a wedding toast can attest, speaking to entertain is a task that requires preparation and practice to be effective.

What are the rhetorical traditions and canons that make up the foundations of public speaking?

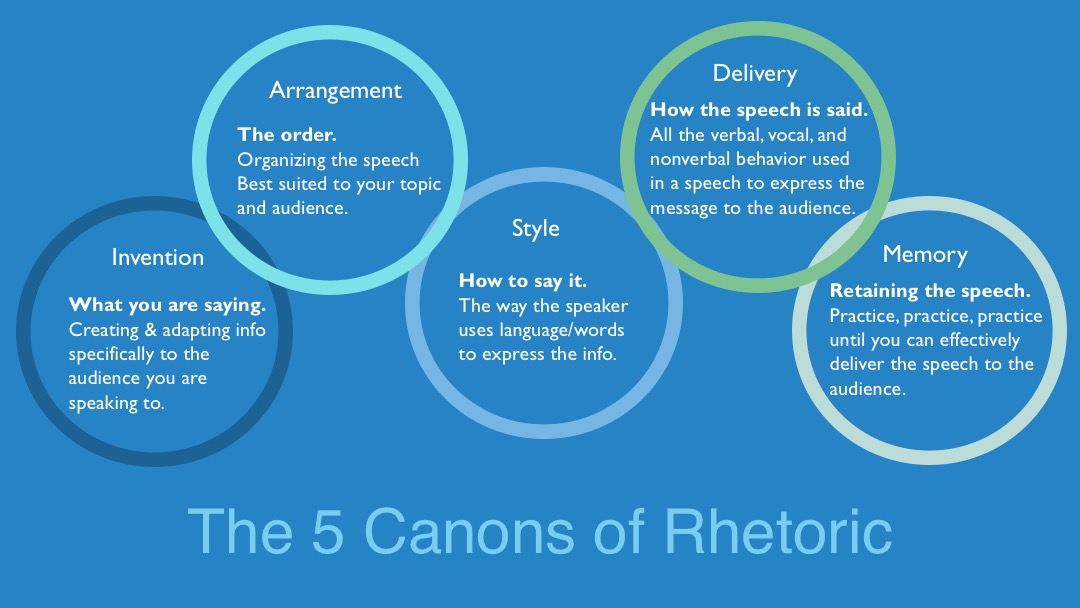

One of the first things you will want to know in order to prepare or make a speech is what makes an effective speech. The measurement of what makes a speech effective has ancient roots in the five canons of rhetoric.

After the Ancient Greeks won back their land, regular citizens had to go to court to plead their case that their stolen land really belonged to them. Cicero, a lawyer, created a five part process, the Five Canons of Rhetoric, to help everyday citizens arrange what they were going to say before the court so they could persuade the judge that it was their land.

These Canons were so effective that we still use them today.

What does the phrase “Five Canons of Rhetoric” mean?

- 5 = number of canons.

- canons = parts.

- rhetoric = discourse or public speaking.

You need to know the 5 canons of rhetoric as the foundation for how you produce your speeches.

How do the elements of the communication model impact effective presentations?

Just like a medical student learns the parts of the body and how they work together to become an effective doctor, we need to learn the parts of communication to become an effective speakers.

What are the parts of the communication model? As you watch this video keep these questions in mind.

- How can understanding this idea help you to connect with your audience?

- Why do you think it’s important to understand that communication is transactional and not just one sided or one way?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wR6csABRGk

The Communication Process Source, by Communication 1020 Videso, Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wR6csABRGk

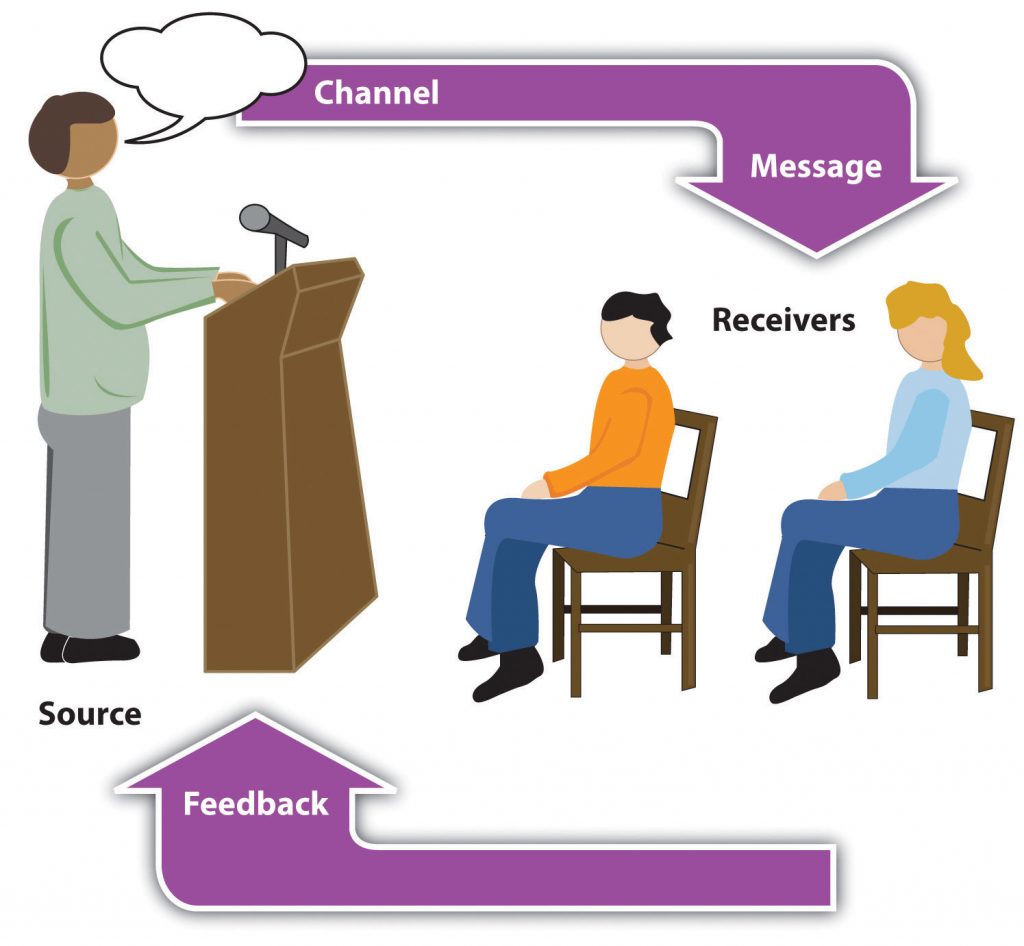

Notice there are several elements in the process and anything can go wrong with an element that prevents our message as speaker from reaching our audience in the way we want it to. This is important to know so we can avoid the problems. Let’s list those communication model elements here.

Sender (sometimes called Source) – source of the message, the speaker.

Receiver – the one who hears the speaker.

Encode – the speaker creates a message.

Decode – the receiver interprets the message.

Message – the information the sender wants the receiver to interpret.

Channel – the vehicle the message is sent on, i.e, sound wave, newspaper, light waves, tv, email, text, etc.

Feedback – the message the receiver sends back in response to the sender’s message, i.e. a nod, eye contact, a frown.

Noise – anything that interferes with the message getting from the sender to the receiver intact. This could be physical noise like loud music playing, chairs that are uncomfortable to sit on, or the receiver is physically sick. It could be psychological or emotional noise. The receiver may have just lost their mother, broken up with their girlfriend, worried about homework, information overload like too many large vocabulary words.

Fields of Experience – add a big circle around the sender and one around the receiver. These represent the experiences, skills, abilities and culture each person brings with them to the communication event. If these circles do not overlap, meaning these two people have nothing in common, it will be difficult for them to communicate. For example, what if they speak different languages? You may have been in a country where you did not speak the language and tried to find a restroom. Not easy when you don’t know the word for “restroom.” Your field of experience (language) did not overlap with your audience’s and so it was difficult to make your message understood.

Context – imagine a flat line drawn under all the elements of the model. This represents the situation the sender and receiver are communicating in. It could be a classroom, a ballpark, funeral or over the internet. Changing the context can change the meaning of a message For example. If we were at a ballpark and I said, “Be quiet.” You may be irritated with me because you liked to cheer your team to victory in a loud voice. If we change context and we are now at a funeral chapel and I said, “Be quiet.” You may realize you are talking too loud, which is disrespectful at a funeral, and quickly go quiet.

You as a speaker want to make it easy for the audience to interpret your message the way you intend. Understanding how each element of the communication model is working will help you do that effectively. Take a look at a simplified version of the model below with you as the speaker. You can already see some of the elements we talked about.

The basic premise of the transactional model is that individuals are sending and receiving messages at the same time.

The idea that meanings are co created between people is based on a concept called the “field of experience.” According to West and Turner, a field of experience involves “how a person’s culture, experiences, and heredity influence his or her ability to communicate with another” (West & Turner, 2010). Our education, race, gender, ethnicity, religion, personality, beliefs, actions, attitudes, languages, social status, past experiences, and customs are all aspects of our field of experience, which we bring to every interaction. For meaning to occur, we must have some shared experiences with our audience; this makes it challenging to speak effectively to audiences with very different experiences from our own. Our goal as public speakers is to build upon shared fields of experience so that we can help audience members interpret our message.

What is the Dialogic Theory of Public Speaking?

Most people think of public speaking as engaging in a monologue where the speaker stands and delivers information and the audience passively listens. Based on the work of numerous philosophers, however, Ronald Arnett and Pat Arneson proposed that all communication, even public speaking, could be viewed as a dialogue (Arnett & Arneson, 1999).

The dialogic theory is based on three overarching principles:

- Dialogue is more natural than monologue.

- Meanings are in people not words.

- Contexts and social situations impact perceived meanings (Bakhtin, 2001a; Bakhtin, 2001b).

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Dialogue vs. Monologue

Even nonverbal behavior (e.g., nodding one’s head in agreement or scowling) functions as feedback for speakers and contributes to a dialogue (Yakubinsky, 1997). Overall, if you approach your public speaking experience as a dialogue, you’ll be more actively engaged as a speaker and more attentive to how your audience is responding, which will, in turn, lead to more actively engaged audience members.

Meanings Are in People, Not Words

Part of the dialogic process in public speaking is realizing that you and your audience may differ in how you see your speech. Hellmut Geissner and Edith Slembeck (1986) discussed Geissner’s idea of responsibility, or the notion that the meanings of words must be mutually agreed upon by people interacting with each other (Geissner & Slembek, 1986).

If you say the word “dog” and think of a soft, furry pet and your audience member thinks of the animal that attacked him as a child, the two of you perceive the word from very different vantage points. As speakers, we must do our best to craft messages that take our audience into account and use audience feedback to determine whether the meaning we intend is the one that is received. To be successful at conveying our desired meaning, we must know quite a bit about our audience so we can make language choices that will be the most appropriate for the context. Although we cannot predict how all our audience members will interpret specific words, we do know that—for example—using teenage slang when speaking to the audience at a senior center would most likely hurt our ability to convey our meaning clearly.

Contexts and Social Situations

Russian scholar Mikhail Bahktin notes that human interactions take place according to cultural norms and rules (Bakhtin, 2001a; Bakhtin, 2001b). How we approach people, the words we choose, and how we deliver speeches are all dependent on different speaking contexts and social situations. On September 8, 2009, President Barack Obama addressed school children with a televised speech. If you look at the speech he delivered to kids around the country and then at his speeches targeted toward adults, you’ll see lots of differences. These dissimilar speeches are necessary because the audiences (speaking to kids vs. speaking to adults) have different experiences and levels of knowledge. Ultimately, good public speaking is a matter of taking into account the cultural background of your audience and attempting to engage your audience in a dialogue from their own vantage point.

Considering the context of a public speech involves thinking about four dimensions: physical, temporal, social-psychological, and cultural (DeVito, 2009).

Physical Dimension – is the room too hot, needs a microphone, dimly lit, distracting poster

Temporal Dimension – is it after lunch when people are sleepy, right before lunch when people are hungry, after a social even-shooting on campus when people are worried.

Social-Psychological Dimension – what are the social status among participants, friendliness, formality?

Cultural Dimension – what are different norms, beliefs, practices, what happens if there are misunderstandings?

References

University of Minnesota. (2011). Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Media References

(2013, February 14). President Barack Obama visits a pre-kindergarten classroom at the College Heights Early Childhood Learning Center in Decatur, Georgia [Image]. National Archives. https://www.obamalibrary.gov/photos-videos

(2016, February 18). President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama greet 106-Year-Old Virginia McLaurin during a photo line in the Blue Room of the White House prior to a reception celebrating African American History Month [Image]. National Archives. https://www.obamalibrary.gov/photos-videos

Communication 1020 Videso. (2021, November 9). Buffett Gates Go Back to School Source [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bu1qHRveG5c

Communication 1020 Videso. (2021, November 9). The Communication Process Source [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wR6csABRGk

Unknown. (2011). Transactional Model of Public Speaking [Image]. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing , University of Minnesota. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/chapter/1-2-the-process-of-public-speaking/

Pixabay user 27707. (2016, January 29). People talking men male [Image]. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/photos/people-talking-men-male-1164926/