Reform & Revolution

Key Concepts

This chapter will prepare you to:

- Define reform and revolution, including the critical differences between them.

- Describe a reform or revolution event from the 20th century, including relevant historical, social, or political context.

- List various artistic reactions associated with war.

- Provide examples of artistic movements that led to social reform and assess their effectiveness.

- Provide an example of civil disobedience and the change that resulted from it.

- Explain the importance of free speech to reform movements.

- Describe an example of bearing witness or storytelling that initiates change.

Reform and revolution have been part of our world since the beginning of civilization. This chapter examines the origins and impact of significant reform and revolution moments from the 20th century. The goal of this chapter is to investigate patterns that emerge from differing conflicts, without judging if a movement is right, wrong, or legitimate. The examples were selected to help illustrate the origins of reform and revolution. We will explore how reform and revolution are documented and how they can lead to open warfare. We will also look at how the arts, culture, personalities, and civil action can work as agents of reform and revolution. We will use our humanities lens to explore reform from the perspective of the individuals and groups engaged in fighting, as well as the public perception created by news media, visual arts, music, and literature.

Change Is the Imperative of Reform & Revolution

Put simply, reform and revolution are actions people undertake to change an existing institution, system, or practice—with the goal of improving it. Reform involves making internal changes or modifications and without completely removing the existing system. For example, American civil rights movements (note the plural usage) that began in the mid-1950s resulted in the reform of laws and policies covering civil rights, voting, and labor. These changes strengthened long-denied human rights protections and delivered them to people of color, women, and migrant workers. The reforms did not drastically change the country’s political structure. At the same time, they ensured fair and equal treatment for all citizens regardless of race, creed, gender, class, ability, sexuality, and ethnicity.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- Do you believe reform achieves equality, liberty, opportunity, and human dignity for all people? Or is revolution necessary to enact change?

When Reform Becomes Revolution

When changes are not being implemented or have not gone far enough, reform may become the catalyst for revolution. The goal of revolution is usually an extreme or complete change to the status quo, including the replacement of the existing authority.

The definition of revolution includes two aspects:

- A forced replacement of a government or social institution to establish a new system

- Multiple events orbiting around and driven by the perceived need to initiate progress

Keep both of these in mind as we explore the reasons why people feel compelled to take up arms, as opposed to using reform to enact change within the existing system. The second aspect is essential for contextualizing how a social movement with a singular goal frequently experiences conflicting ideological beliefs on how to achieve it.

The American Revolution(1775-83) led to the eradication of the existing political power structure, colonial rule under Great Britain. From this armed revolution, emerged the United States of America, an independent self-governing nation. Coming on the heels of the American Revolution, social, political, and agricultural tumult in France would culminate in the French Revolution (1787-99). This violent uprising led to the downfall of the monarchy ruled by King Louis XV and the rise of Napoléon Bonaparte.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Non-commercial use of copyrighted material is free and open. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8413164j/f1.item

Closely following the start of the French uprising, the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) began in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Saint-Domingue, one of the most successful colonies in the Americas, had been built on the backs of slaves. After the slaves fought for and won their freedom from French authority, they created Haiti, the first country to be founded by slaves.

The revolution’s course was complicated by intervention from the newly founded United States of America. American leaders, such as Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, supported the white population of Saint-Domingue, in part, because of fears that the slave unrest would spread northward. Jefferson found himself in a political conundrum. He firmly believed in the foundational ideas behind the French Revolution. On the other hand, he kept slaves for his financial, cultural, and political benefit.

As the revolution continued, refugees fleeing the war in Saint-Domingue arrived on the shores of Virginia, Philadelphia, and New York of the United States. Most of them were white, and many were slave owners accompanied by their slaves. These outsiders supplied firsthand accounts of slaves violently turning against their masters, which confirmed the fears of alarmed American lawmakers. After all, many of these government leaders acquired their wealth using slave labor. In 1798, the political xenophobia became codified into law as the Alien and Sedition Acts. An increasingly xenophobic American public made life unbearable for many of the recent immigrants. Some decided to return home, despite the still-tenuous political situation in Saint-Domingue. As we can see from this timeline, the Haitian Revolution was influenced (perhaps even driven) by the American and French uprisings that preceded it.

Revolution Is Not War

While armed conflict is frequently involved, war may not be necessary to achieve revolutionary change. In 1994, military leader Yahya Jammeh gained control of the Gambian government after a bloodless coup. Then in 2016, a democratic revolution ousted Jammeh as military and political ruler—a position he maintained with brutal authority for 22 years. One event among many that prompted the change was the death of opposition activist, Solo Sandeng, who was tortured and killed while in police custody. Social media made evidence of the violence readily available for Gambians to see and understand. For the first time in decades, people who had no interest in politics were expressing concern over Jammeh’s violent action against a political opponent. Gambian voters understood that their silence meant tacit complicity; they took to the polls to oust Jammeh and his rule of terror.

Following the election, Gambians sought lasting change. They understood that revolutionary actions required follow-up reforms to heal the country’s collective trauma. The newly elected Gambian government created the Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparations Commission (TRRC). The TRRC provides a platform for sharing stories of trauma, grants reparations for victims, documents acts of violence, and holds perpetrators accountable for their crimes. Interviews with killers, victims, and witnesses are live-streamed and archived on YouTube, making the process transparent.

Why We Fight: Examining Historical Events

The following examples present several 20th-century reform and revolution events. We will examine causes, key developments, and the consequences of war, as well as reconciliation efforts and political initiatives. These artifacts are presented from the perspective of participants, combatants, and civilians, as well as news, art, and literature.

Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist papers:

“To judge from the history of mankind, we shall be compelled to conclude that the fiery and destructive passions of war reign in the human breast with much more powerful sway than the mild and beneficent sentiments of peace; and that to model our political systems upon speculations of lasting tranquility, is to calculate on the weaker springs of the human character.”

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Do you think Hamilton’s statement is correct? Or is war an inevitable aspect of life?

- Digging deeper, what reasons would be compelling enough for people to protest or to take up arms rebel against the status quo?

- Do you believe the primary motivation for going to war is the fear of kill or be killed? Or is the reason more complex? What compels countries to spend vast sums of money on troops, weapons, and warfare?

- As we have considered why we fight and how we process those experiences as human beings, have your views on war changed? Do you think it is always justified?

Whose Story Is It?

One thing often overlooked is whose stories get erased as history is documented and told. To critically analyze an artifact of reform or revolution, we must examine the unofficial, as well as official versions. We must often address contradictory messages about why we fight. For example, are we waging war to defeat political oppression? Or is there another agent driving the conflict, such as religious ideology or financial gain? Keep these various perspectives and challenging questions in mind as we examine reform and revolution artifacts from the 20th century.

Credit: Eric Durr.

New York National Guard. Public Domain. https://www.nationalguard.mil/Resources/Image-Gallery/News-Images/igphoto/2002042273/.

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks is a graphic novel about the 369th Infantry Regiment. This all-black American infantry unit fought during WWI. The homecoming parade honoring the decorated war heroes turns somber when they learn of the notorious race riots of the Red Summer of 1919. The final panel’s caption reads:

“It’d be a nice story if I could say that our parade or even our victories changed the world overnight, but truth’s got an ugly way of killin’ nice stories. The truth is that we came home to ignorance, bitterness, and somethin’ called the ‘The Red Summer of 1919,’ some of the worst racial violence America’s ever seen. The truth is that our fight, and the fight of those who looked up to us as heroes, didn’t end with the ‘the war to end all wars.’”

Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence is a textual artifact that marks the birth of the United States. It also defines universal rights guaranteed to all people, not just its citizens. The document was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, as part of the announcement that the 13 American colonies were no longer members of the British Empire. 56 representatives of the 13 newly independent sovereign states signed the declaration.

This document defines the American view of freedom and revolution, underscoring particular cultural perspectives. The historical context plays a key and disconcerting role. Slave labor was central to the flourishing of the American economy. Nevertheless, the declaration states that all men are created equal. This equality did not exist for the slaves, who earned no wages and were treated as property to be sold, branded, and traded. For voting and taxation, they counted as only three-fifths of a person. Interestingly, the original draft alluded to the immorality of slavery. However, this mention was removed for political expediency.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- How does the Declaration of Independence shape the definition of freedom? How does the contradiction of slavery affect this definition?

- Do you think the declaration justifies the 13 colonies going to war against Great Britain? What other contextual factors might be involved?

- The declaration is explicit in defining rights for men. Why do you suppose it omits women, LGBTQ, or non-binary? Why do you think it makes no mention of a man’s race?

French Revolution

For many Europeans, the French Revolution remains a pivotal moment in history. It is a touchstone event, highlighting the will of the people versus totalitarian institutions. Toward the end of the 18th century, unrest was growing among urban and rural peasants. France had experienced two decades of poor harvests, triggering rising costs for bread, a staple food item for most of the population. Resentment festered from heavy taxation, necessitated by the excessive spending habits by King Louis XVI. The monarch provided no support or relief for those struggling with crop failure and famine. Public complaints and discontent turned into rioting and looting, which soon spread across the country. Bastille Day, July 14, 1789, marks the start of the French Revolution. On this date, people stormed the Bastille fortress in Paris to obtain guns and gunpowder. This people’s revolution resulted in the removal of the monarchy, along with the feudal taxation and social system.

World War I

World War I (WWI), or the Great War, began on July 28, 1914, and lasted until November 11, 1918. More than 9 million combatants and 7 million civilians died as a result of this armed conflict that involved most of Europe, Russia, the United States, and the Middle East. The triggering event was the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne, Franz Ferdinand, by a South Slav nationalist named Gavrilo Princip. Hostilities between Serbia and Austria-Hungary that had flared up during the Balkan Wars (1912-13) added to the tense situation following the assassination in 1914. Existing European alliances came into play, creating a situation where armed conflict seemed inevitable. These alliances created two armed camps: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy; and the Triple Entente of Britain, Russia, and France. Russia, an ally of Serbia, mobilized their army to defend against an attack from Austria-Hungary. Germany interpreted this as an act of war, declared war on France, and pulled Great Britain into the conflict.

World War II

World War II (WWII, 1939-1945), the second global war, is regarded as the deadliest conflict in human history. Total casualties are estimated at 50-85 million people, which include over 6 million people executed in Nazi concentration camps. The roots of WWII began with the reparations of World War I. Several countries, Germany in particular, were discontent with the terms of the Treaty of Versailles (1919). Adolph Hitler used this time of political and economic uncertainty to rise to prominence in the public eye. He spread propaganda that blamed Jewish people for Germany’s defeat in World War I. Following his election as Chancellor in 1933, Hitler drafted laws to exile Jewish people from society. And he continued to disseminate propaganda that supported these laws. Because these legislative moves occurred against the backdrop of prosperity and development, they went mostly unnoticed until the Nazi party began enforcing the laws they had put into place.

On the other side of the world, Japan had its own motives for joining the war. Korea had already been taken over in 1910, predating WWI. Several years before Germany’s annexation of Poland in 1939, Japan invaded China intending to colonize Asia and the Pacific. In September 1940, Japan formally entered WWII by signing the Tripartite Pact, allying with Germany and Italy. The United States entered the war after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. On August 6, 1945, the US bombers dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, killing an estimated 70,000 people from the detonation. At least 80,000 more people succumbed to related physical injuries and radiation poisoning. Three days later, US bombers dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. The conservative death toll, which includes immediate and subsequent deaths, is estimated at 75,000 people. These are the only two uses of nuclear bombs in warfare history. Japan submitted its intention to surrender to the Allied powers on August 10, 1945.

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials that were held following WWII became a model for retributive justice, international criminal law, and the definition of a crime against humanity. The trials documented Nazi war crimes and sentenced the perpetrators of murder, torture, mutilation, imprisonment, persecution, enslavement, and other inhumane actions. Truth commissions organized after the trials attempted to apply restorative justice, which investigates war crimes and makes recommendations on preventing human rights violations. These examples of judicial reform are undergirded by dual, complementary aims: holding war criminals accountable for past actions and empowering victims by documenting their stories.

The Bolshevik Revolution

Credit: US War Department. National Archives and Records Administration. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Enemy_Activities_-_Arrests_of_Alien_Enemies_-_Bolsheviks_in_Russia_-_Bolshevik_Revolution_in_Russia._Soldiers_of_the_Bolshevik_Army_march_around_the_square_near_the_Kremlin._In_the_foreground_is_a_mounted_Cossack(…)_-_NARA_-_31477940.jpg

Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov, more commonly known as Vladimir Ilich Lenin, was one of the leading political figures and revolutionary thinkers of the 20th century. He masterminded the Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and helped found the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Two personal crises that befell Ulyanov during his youth were strong influences on his anti-establishment views as an adult. The first was when his father died after being harassed by the government. The second blow was the execution of his elder brother, who was convicted of conspiring to assassinate the Russian emperor. Ulyanov pursued a law degree at Kazan University, where he was soon expelled. Despite being denied readmission, he completed his studies, passed his examinations, and graduated in 1891. In his law practice, he confronted a corrupt legal system that heavily favored the wealthy and upper class.

Ulyanov gave up his practice, moved to St. Petersburg, and became a professional revolutionary. In 1895, he was arrested, jailed, and exiled to Siberia. After returning from exile, he adopted the pseudonym Lenin and spent most of the next 15 years in western Europe. During his time away from Russia, he emerged as a prominent revolutionary. He became the leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social-Democratic Worker’s Party.

In 1917, Lenin perceived that post-WWI Russia was ripe for change. Lenin returned home and started working against the provisional government, which had overturned the tsarist regime in February. On October 24-25 of that same year, Lenin instigated the Bolshevik (October) Revolution, overthrowing the provisional government. Three years of civil war followed, during which Lenin’s Bolsheviks assumed total control of the country. During this period of upheaval, conflict, and famine, Lenin demonstrated a chilling disregard for the suffering of his countrymen and mercilessly crushed any opposition to his will. Lenin also had a practical side. When his efforts to transform the Russian economy to a socialist model stalled, he introduced the New Economic Policy. This policy permitted some measure of private enterprise, which the socialist government continued for several years after Lenin’s death.

In 1918, Lenin survived an assassination attempt but was severely wounded. The injuries affected his health, and in 1922 he suffered a stroke from which he never recovered. Lenin died on January 24, 1924. His corpse was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum on Moscow’s Red Square. His Union of Soviet Socialist Republics lasted for 74 years until political turmoil (another people’s revolution) dissolved the union in 1991.

China’s Cultural Revolution

Credit: Daniel Case. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sculpture_of_revolutionary_struggle_at_Mao_Zedong_Mausoleum,_Tiananmen_Square.jpg

Mao Zedong led an armed peasant revolution that swept out the imperialist Chinese government and replaced it with a communist one. His other accomplishments include founding the Red Army, modernizing Chinese industry and manufacturing, and increasing the country’s population.

Born in 1893 to peasant farmers, Mao developed his anti-imperialist, pro-nationalist outlook early in life. When he was 27 years old, Mao organized a branch of the Socialist Youth League and, soon after, attended the First Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Mao was forced to flee his home province after organizing an activist network of farmers and peasants. He moved to the large urban city of Guangzhou, where he ran propaganda campaigns for the Nationalist Party and attended the Peasant Movement Training Institute.

After evading a purge of communists by Nationalist Party leader Chiang Kai-shek, Mao returned to his rural roots. Noting the growing power of the peasant movement, Mao predicted the peasantry would “rise like a tornado or tempest—a force so extraordinarily swift and violent that no power, however great, will be able to suppress it.”

In 1927, Mao led a peasant uprising using guerrilla warfare tactics that would later be adopted by the Red Army. By 1930, he was leading the Red Army, and in November of that year, Mao challenged Chiang Kai-shek in open warfare. At first, the battle went in favor of the Red Army; however, they eventually were crushed. The defeated army, Mao, his children, pregnant wife, and younger brother fled the battlefield to make their way home in what is now called the Long March (1934-1935). The Red Army began the trek with 86,000 troops. Along the way, Mao and his communist followers were bombarded from the air and attacked on the ground. Six thousand miles later, only 8,000 survivors managed to reach their destination. Two of Mao’s children and his brother did not survive the trek. The Long March was a critical turning point for Mao’s leadership within the party. The personal tragedies suffered during the march proved to be a compelling recruitment tool. The CCP and Red Army ranks swelled with new members. The growing threat of invasion by Japan helped unify the nationalist and communist factions, and in 1937, the two parties forged a formal agreement of unity.

From 1936-1940, while many communists were fighting Japanese incursions into China, Mao spent this time writing about his revolutionary goals. In 1943, Mao was officially instated as leader of the CCP. On October 1, 1949, Mao proclaimed the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a single-party state controlled by the CCP. In 1957, he launched the Great Leap Forward. He planned to use mass mobilization of labor to boost agricultural output, which would facilitate the transition to a modernized industrial economy. However, the strategy backfired, and agricultural output declined. The diversion of resources into industrialization projects, coupled with poor harvests, caused widespread famine and the deaths of millions of people.

His political authority severely weakened, Mao abandoned his disastrous economic policy and launched the Cultural Revolution (1966). Mao drove his campaign to revive the revolutionary spirit with a totalitarian intolerance for any challenges to his authority. His mandates attacked all forms of traditional culture. Intellectuals—typically, doctors, teachers, artists, musicians, and scholars—were labeled bourgeois traitors to the party. One-and-a-half million people died, and untold centuries of cultural heritage were destroyed. Despite those faltering early steps, China’s economy flourished through the end of the 20th century and dramatically expanded at the start of the 21st.

Truth Commissions Around the World

The Gambia was not the first country, nor will it be the last, to implement a truth commission in the wake of a revolution. In the last three decades, more than 40 countries, including Ghana, Canada, Guatemala, Liberia, Rwanda, Morocco, Philippines, Kenya, South Korea, and South Africa, have established truth commissions as an act of reform against human-rights abuses. Many of these past injustices are rooted in a sustained, pervasive, and systemic disregard for human rights. These commissions also create permanent public records that officially document the facts surrounding a crime against humanity. These facts include the suffering of the victims, human-rights violations committed, and the identity and actions of the perpetrators. While not perfect and sometimes problematic, truth commissions offer restorative justice that has helped millions of victims of colonialism, racism, nationalism, totalitarianism, kleptocracy, slavery, bigotry, misogyny, and xenophobia.

Art as a Medium of Reform

Art’s potential to inspire social and political change lies with its ability to communicate people’s innermost thoughts and feelings. Whether via poetry or storytelling, through a visual or audio medium, art can provide a comfortable way to engage in an uncomfortable conversation.

Bearing Witness through Art

The artists, musicians, authors, poets, and filmmakers featured in this section have created works that serve purposes beyond artistic creation. These art artifacts also provide moral accountability and historical documentation. This two-fold function empowers art with the role of bearing witness to reform, revolution, civil rights, genocide, war, ethnic cleansing, oppression, conflict, social justice, prejudice, and the myriad of other human experiences.

In an interview on Radio West, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Thanh Nguyen spoke frankly about the Vietnam War from the perspective of a refugee. He discussed how American filmmakers and the government represented Vietnam during the war and how they regarded Vietnamese refugees—if they regarded them at all.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Why were Vietnam and its people represented as mere props in a kind of proxy war with the Soviet Union? Can you think of another historical example of an artifact bearing witness to the human side of war and its aftermath?

- How were street art, poetry, social media, and filmmaking used to organize what came to be known as the Arab Spring movement that occurred in parts of Africa and the Middle East?

- Can you come up with artwork artifacts associated with the Hong Kong protests that began in Spring 2019? (Hint: Start with this ArtnetNews story.)

The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was a social, artistic, political, and cultural movement that began near the end of WWI and lasted into the 1930s. Harlem, New York, was a magnet for black writers, painters, musicians, photographers, poets, and scholars. Many of these artists arrived as part of the Great Migration—a mass exodus of blacks fleeing the South and its systemic racial discrimination.

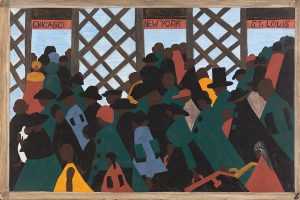

Credit: Jacob Lawrence. The Phillips Collection. Fair Use of copyrighted material. https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series/panels/1/during-world-war-i-there-was-a-great-migration-north-by-southern-african-americans.

Millions of black citizens left rural southern states for urban centers in the northern and western states. In 1940, Harlem artist Jacob Lawrence created a 60-panel painting series called The Migration Series to bear witness to the experiences of these relocated black Americans.

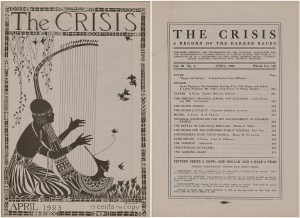

The Harlem Renaissance gave black thinkers the freedom, inspiration, and community support to explore and share their creative passions. W.E.B. Du Bois was editor of The Crisis, the official journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The magazine published many poems, stories, and visual works by Harlem artists. Some notable names from this period include Langston Hughes (poet), Countee Cullen (poet), Arna Bontemps (writer), Zora Neale Hurston (writer), Jean Toomer (writer), Walter White (civil-rights activist), Claude McKay (writer), and James Weldon Johnson (writer).

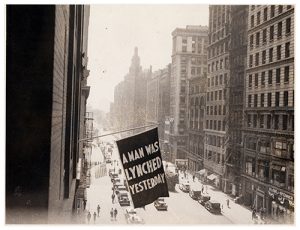

Credit: NAACP. Library of Congress. Public Domain. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/naacp/the-new-negro-movement.html#obj8.

Context is critical for understanding how important it was for black Americans to have a thriving, unfettered, cultural community like Harlem. The renaissance was much more than a source for new literature and art. The movement cultivated racial pride, social progress, and political activism in parallel with the NAACP’s New Negro campaign to lobby for a federal law against lynching. Radical musical stylings in jazz and blues attracted trend-seeking white customers to nightspots like the Cotton Club, where interracial couples danced. Nightclubs gave blacks and whites the chance to mingle socially, unjudged, which may have helped relax traditional racial attitudes among younger generations of white Americans.

War and Poetry

Poetry and art are useful media for processing human experiences, as well as broadcasting these experiences across social boundaries. British poet Wilfred Owen wrote many war poems over the course of WWI, providing an artifacts timetable that tracked his changing opinions. One of his best-known works, Dulce et Decorum Est (It Is Sweet and Fitting to Die), describes the horrors of men in trenches being assaulted with chlorine gas. Owen concludes the poem with the following line, “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.” The Latin phrase is an inspirational quote from the Roman poet Horace. In the face of grim reality, Owen rejects this patriotic slogan.

Credit: Suheir Hammad. “Poems of war, peace, women, power.” TEDWomen 2010. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International. https://www.ted.com/talks/suheir_hammad_poems_of_war_peace_women_power.

Palestinian-American poet Suheir Hammad is well known for her political poems about war. In “Break Clustered” (time marker 02:38), she concludes, “Do not fear what has blown up. If you must, fear the unexploded.”

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- How do Hammad’s imagery, tone, and use of point of view to bear vicarious witness to the violence of war and the experiences of women in war? How would you interpret the meaning of the poem’s title?

- What would it be like to fight for freedom abroad while your loved ones are being oppressed at home? What does it mean to fight a war abroad and at home?

War and Photography

In April 2004, graphic photos (article includes a photo of a corpse) of prisoners being tortured and abused were leaked to the press. These prisoners of war were being held at Abu Ghraib, an American military prison located in Iraq. If valid, the photos presented proof of human-rights crimes that violated the Geneva Convention safeguards for prisoner treatment in a time of war.

Over the last century, the nature of war reporting in the United States has significantly changed during major conflicts. During WWII, much of the reporting included patriotic messages and shows of public support. This pro-war attitude did a 180-degree flip during the Vietnam War when positive messages from the White House contrasted sharply with footage taken by journalists in the field and those covering the protests at home.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- Do you think a report on violence and abuse against prisoners at Abu Ghraib would have been as impactful if it were only verbal descriptions, without photos? Why do you think that is?

- Compare the open access given to journalists during the Vietnam War versus war-reporting policies enacted during the Gulf War.

- How do devices such as cell phones, digital cameras, and social media change the nature of reporting on reform and revolution, particularly during wartime?

- Unlike artists and activists, reporters have a responsibility to provide unbiased reportage. How realistic is this expectation? Do you think this is even possible?

- Do you think some war-related images should not be shown or shared with the public? Or do people have the right to full access, regardless of how shocking or explicit the images are?

War and Music

Music can profoundly affect the war effort, whether in support of or as a rejection. During WWI, the United States military assigned song leaders to training camps as a means of fostering healthy activities. Soldiers also adopted singing as a coping mechanism, making it part of the trench culture and giving WWI the nickname the Singing War. The most famous incident involving singing soldiers is known as the Christmas Truce (1914). On Christmas Eve, homesick soldiers from Britain, Belgium, France, and Germany began singing carols in their trenches. The singing led to holiday greetings and signs promising not to shoot. On Christmas Day, allies and enemies emerged from their trenches and exchanged gifts.

During WWII, performers frequently visited war camps and provided live entertainment to boost troop morale. British singer Dame Vera Lynn, the Forces’ Sweetheart,” became famous for her pro-troops support. She wrote music supporting the war effort and traveled abroad to sing for allied troops. One of her best-known songs, “We’ll Meet Again (1939),” promises a reunion for troops stationed across Europe. The chorus of the song says:

We’ll meet again

Don’t know where

Don’t know when

But I know we’ll meet again some sunny day

Keep smiling through

Just like you always do

‘Till the blue skies drive the dark clouds far away

In more recent times, Toby Keith stands out for visiting troops and supporting the war effort. In December 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan in response to the September 11 attacks in New York and Washington, DC. Six months later, May 2002, Toby Keith released the single Courtesy of the Red, White & Blue (The Angry American).” Widely popular with troops and civilians, Keith’s song celebrates the legacy of America’s armed defense of liberty and justice. The lyrics reference his father’s military service and makes the following promise to the enemies of America:

Justice will be served and the battle will rage

This big dog will fight when you rattle his cage

And you’ll be sorry that you messed with

The U.S. of A.

‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass

It’s the American way

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

In addition to reading the lyrics, listen to the music that accompanies these two songs.

- How would you describe the mood or emotion expressed in “We’ll Meet Again?” In “Courtesy of the Red, White & Blue (The Angry American)?”

- Can you find some historical, social, political, or personal context that helps explain the widely divergent messages in these two musical artifacts?

Reform through Civic Action

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution guarantees citizens freedom of assembly (protest), petition, speech, and the press. This promise safeguards people who disagree with government policies against retribution or punishment, facilitating political and social reform through non-violent means. These civic actions can take many forms: sit-ins, flashmobs, boycotts, prayer vigils, marches, public demonstrations, hunger strikes.

The Black Lives Matter movement began in protest of George Zimmerman being acquitted of murder in the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012. Fast forward to May 25, 2020, when George Floyd’s death while in police custody was captured by the cell phones of onlookers. The video footage went viral, and the Black Lives Matter movement erupted into a tidal wave of social media protests and in-person demonstrations across the United States.

Other examples of citizens exercising their First Amendment rights include the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 28, 1963), Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam (October 15, 1969), Million Woman March (October 25, 1997), People’s Climate March (September 21, 2014), and most recently, Black Lives Matter (June 6, 2020).

First Amendment protections also mean that a single person can elicit change through non-violent protest. During a preseason game of the National Football League (NFL) in 2016, quarterback Colin Kaepernick demonstrated against police brutality and racial inequality by remaining seated during the National Anthem. Initially, Kaepernick carried out his public protest alone. By season’s end, he had been criticized by the president, joined by hundreds of his football peers, and become the topic of national debates. Fans indicated their support by buying his jersey—sales skyrocketed. One might even argue that the surge of support for Black Lives Matter in 2020 had been primed four years earlier by Kaepernick’s silent, personal protest.

That is not to say Kaepernick did not suffer for his civic actions. At the end of the season, the team released him. Other team owners, afraid the publicity backlash would damage profits, made no offers to sign him. He has not played in a professional game since. Private organizations are not required to protect free speech. Team owners can force players to comply with policies that establish their own (self-serving?) expectations of appropriate conduct.

Another example of one person being a lightning rod for change comes from Sudan, Africa. In April 2019, a young woman named Alaa Salah led protests calling for the removal of President Omar al-Bashir. The movement eventually sparked an armed revolution that ousted Bashir by force. What makes this civic action particularly significant is that Salah lives in a predominantly Muslim country where women are expected to be subservient to men. Furthermore, she publicly spoke out against a government with a long history of violent suppression.

In other parts of the world where these freedoms are not guaranteed, anti-government protests can be deadly for the participants. This iconic picture of a man standing in the path of oncoming tanks documented citizen demonstrations in China. The pro-democracy protesters, mostly students, marched through Beijing to Tiananmen Square in response to the recent death of Yaobang Hu. Hu worked with the CCP to introduce democratic reform before being forced to resign as General Secretary. Over several weeks, tens of thousands of people joined the students in Tiananmen Square in calling for democracy, free speech, and a free press in China. On June 3 (or 4), 1989, the government sent tanks, artillery, and soldiers to Tiananmen Square. The army killed perhaps thousands of demonstrators in what became known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre (June 3-4, 1989).

The Arab Spring (2011) was a series of anti-government protests that took place in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Yemen, Syria, and Bahrain. Street demonstrations took place in Morocco, Iraq, Algeria, Iranian Khuzestan Province, Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, and Sudan. Social media, especially Facebook, was instrumental in coordinating these gatherings. In Syria, the government responded to the pro-democracy demonstrations by sending tanks, heavy weapons, and troops to slaughter villagers across the country.

Questions for Critical and Creative Thinking

- How many types of non-violent protest can you come up with? Check your list against this one provided by The King Center.

Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is the refusal to comply with a government law or policy on the grounds it is immoral. The term comes from an essay, “Civil Disobedience,” written by 19th-century writer and philosopher Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau wrote the essay after being imprisoned for refusing to pay a poll tax, which he did in protest against the invasion and occupation of Mexico by the United States.

Thoreau believed that the “government which governs best, governs least,” for which some people deemed him an anarchist. Thoreau was not in favor of eradicating government, but rather, in fewer regulations telling people what to do. Thoreau puts forward the idea that people have a duty is to live by their conscience. This commitment to moral law overrides the duty to obey an institutional one. Encouraging non-compliance challenges the convention that good citizen is a law-abiding one. Thoreau asserts that a good citizen is someone who follows his conscience, even if it means not abiding by the law.

Another component of civil disobedience is that when people break the law on moral grounds, they do so peacefully. Indian social reformer Mahatma Gandhi exemplified non-violent civil disobedience. During his campaign of civil disobedience against British rule, Gandhi famously said, “They may torture my body, break my bones, even kill me. Then they will have my dead body, but not my obedience.”

In a contemporaneous example, University of Utah student Tim DeChristopher bid on drilling rights to public lands being auctioned to private gas and oil companies. During the December 2008 auction, he bid $1.8 million to acquire leases on 14 parcels, with no intention of paying for them. DeChristopher used his trial and the surrounding media coverage to explain that he was stopping an illegal auction of publicly owned land rights. During an appeal hearing, his attorney Ron Yengich said, “Mr. DeChristopher’s actions effectively stopped the lease process and gave the new administration the opportunity to review it and then move forward.”

Yengich was referring to the new administration under President Obama, which in the spring of 2009, canceled 77 of the auctioned drilling leases. This act of civil disobedience resulted in DeChristopher serving 21 months in prison. A couple of years later, DeChristopher told Bill Moyers, “When I went into this, I was pretty focused on the direct impacts of my actions, keeping that oil under those parcels and stopping this particular auction. I think those impacts turned out to be much more important than just keeping that oil in the ground.”

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- In the DeChristopher example, what contextual factors made civil disobedience so impactful as a form of protest?

- Do you believe DeChristopher’s sentence should have been reduced after the drilling leases were canceled? Why or why not?

Freedom of Speech

Among western democracies, the United States stands alone in upholding free speech to the point of not censoring hate speech. Hate speech is malicious oral or written language used against a person or people on the basis of race, religion, sex, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, and other groups.

This reluctance to regulate the things people say, for better or worse, has a historical context. The American concept of freedom of speech is virtually inseparable from freedom of religion. Both of these freedoms arose as a dissent to the restrictive Puritanical and Anglican culture of British society. Only clergymen and governors could engage in free expression without fear of reprisal, and they were reluctant to extend this power to the public at large. The idea of giving all citizens the right to speak their mind with impunity, regardless of social status, made its way into the First Amendment:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

This background may explain why the United States insists on protecting all speech, as opposed to preventing or prohibiting some speech.

On August 12, 2017, the Unite the Right group held a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Protestors openly displayed Nazi swastikas and chanted, “You will not replace us. Jews will not replace us.” and “White lives matter.” Because this happened in America, the speech and swastikas were protected under the First Amendment.

Government censorship of hate speech and actions is more commonly seen in other democratic countries, such as Germany, Canada, Britain, Denmark, and New Zealand. Two weeks before the Charlottesville incident, two Chinese tourists were arrested in Berlin for openly using the Nazi salute. They took photos of each other standing and saluting in front of the Reichstag building. Shortly after WWII, Germany banned the public use of Nazi gestures or symbols.

The Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, Kansas, is a small, independent church that teaches its followers that God hates homosexuals. They also believe high-profile tragedies—such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Sandy Hook shooting, and Boston Marathon bombing—are God’s retribution for allowing sin to spread unchecked. Their protests frequently target funerals, where members display signs reading “God Hates Fags,” “Thank God for Dead Soldiers,” “Thank God for 9/11,” and “God: USA’s Terrorist.” Branded as a hate group by the Anti-Defamation League and Southern Poverty Law Center, church members are also banned from entering Canada and the United Kingdom. Despite legal challenges against the church, the United States Supreme Court ruled its members’ actions and slogans are protected under the First Amendment.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Do you think the members of Westboro Baptist Church is using hate speech? Should they be banned and their signs censored?

- Do you think speech should always be free and unregulated? Or should hate slogans and swastikas be censored under certain circumstances?

In 1987, artist Andre Serrano exhibited series of photographs showing religious objects submerged in fluids, including one of a crucifix immersed in urine. In the United States, the public outcry that followed turned into a political debate over whether to withdraw government funding for public art.

- Do you think Serrano’s artwork constitutes a type of religious hate speech? Should it be banned or censored? Should it be supported by public funds?

Bearing Witness through Storytelling

Bearing witness is a civic action that involves observing events without intervening and changing their outcome. On-the-scene news stories and documentary films are examples of bearing witness. As mentioned previously, paintings, poetry, music, and other art forms can also bear witness. What all of these have in common is that they use storytelling to effect reform and change indirectly. Storytelling can be a powerful motivator for interventionist actions such as civil disobedience, live demonstrations, and armed uprisings.

James Orbinski is a physician, former director of the humanitarian group Doctors Without Borders, and winner of the 1999 Noble Peace prize. In his book, An Imperfect Offering, Orbinski asks, “How am I to be, how are we to be in relation to the suffering of others?” He asks this question after decades of bearing witness to famine, disease, war, and genocide. Orbinski sees his role in eliciting change as being a witness to people who are suffering, refusing to remain silent, and sharing their stories.

Observing without getting involved can present particularly difficult ethical challenges. American news photographer Malcolm Browne captured the self-immolation of a Buddhist monk during the Vietnam War on film. The monk, Thích Quảng Đức, set himself on fire to protest the persecution of the South Vietnamese government’s persecution of Buddhists. Browne was the only photographer present and shot ten rolls of film. Years later, Browne wondered if his presence contributed to the monk’s suicide; that if he had not been there to bear witness:

“[The monk] probably would not have done what he did—nor would the monks in general have done what they did—if they had not been assured of the presence of a newsman who could convey the images and experience to the outer world. Because that was the whole point ole point — to produce theater of the horrible so striking that the reasons for the demonstrations would become apparent to everyone. And, of course, they did. The following day, President Kennedy had the photograph on his desk, and he called in Henry Cabot Lodge, who was about to leave for Saigon as U.S. ambassador, and told him, in effect, ‘This sort of thing has got to stop.’ And that was the beginning of the end of American support for the Ngo Dinh Diem regime.”

Modern technology—such as television, broadband internet, social media platforms, and cell phones—makes it possible for virtually anyone, to bear witness to any event, happening anywhere in the world. Whereas previously, we may have only had access to verbal or written accounts; now, we can see events unfold in real-time.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Consider the responsibility of bearing witness to a reform or revolution event. Does the witness have a responsibility to intervene if it means saving a life or preventing a disaster? What if they are a journalist? What if they are a doctor?

- Do you think non-interventionist storytelling can be as effective in creating change as an armed uprising or military action? For war?

- Have you personally witnessed a reform or revolution event? Did you get involved? Why or why not?