Human Rights & Genocide

Key Concepts

This chapter will prepare you to:

- Identify and discuss philosophical ideas about the value of human life.

- Understand and discuss the term genocide and its legal implications.

- Describe situational psychology and why people sometimes get involved in outrageous acts of violence against another human being.

- Describe the process of dehumanization.

- Provide examples of alternatives to military intervention in instances of mass atrocity and genocide.

- Evaluate the philosophical concept and policy regarding “The Responsibility to Protect.”

- List some psychological explanations for why ordinary people could possibly commit horrific crimes.

This chapter explores human rights and responsibilities in a global society, including how we define and measure the value of human life. As part of this analysis, we will look at how genocide, a crime against humanity, reduces the value of human life to zero.

Credit: UN Photo/Michos Tsovaras. Fair Use of copyrighted material. https://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/144/0144182.html

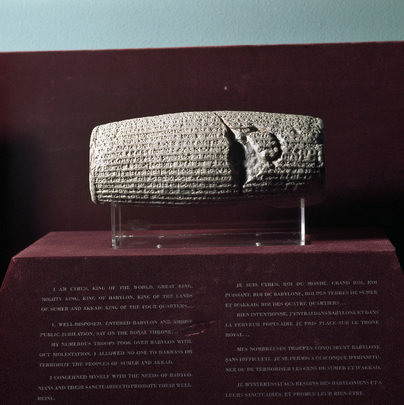

The United Nations (UN) pinpoints the origin of human rights to the Edict of Cyrus, inscribed on a clay cylinder in the year 539 BC. The edict proclaims that when Cyrus the Great conquered Babylonia, he freed Jewish captives and supported freedom of worship. The British Museum has a translation of the inscription. Since then, various civilizations have navigated the concept of human rights within their unique social and power structures. Many have considered whether equal rights and privileges should be extended to all people.

The first part of the chapter examines the historical, social, and political context for acts of genocide and other human rights violations. Looking through our humanities lens, we will consider how morality, hope, and heroics play roles in preventing mass atrocities, as well as facilitating the healing process. The second half unravels the complex reasons behind why people devalue and harm each other. We will examine the value of human life from philosophical, social, and psychological perspectives.

Genocide: Crimes Against Humanity

The Holocaust (1933-1945) of World War II is perhaps the highest-profile and best-documented example of genocide in world history. Mass atrocities like genocide are typically preceded by a social, economic, and political context that demonizes and devalues the people being targeted. Public perception views the target as a social ill, economic burden, or enemy of the state. Government-issued propaganda and legislation marginalize the targeted group, cutting them off from the rest of society.

Defining Genocide

The term genocide was first presented by Raphael Lemkin, a Jewish jurist from Poland who served as war advisor to the United States government. Lemkin was lost 49 relatives during the Holocaust and sought to legally prosecute what he observed were crimes against humanity unfolding on a massive scale. He fused the Greek word genos (family, tribe, or race), with the Latin word cide (to kill).

The term sets a legal precedent by defining the mass killing of a particular ethnic group as a crime. Prior to Lemkin, only the murder of an individual had legal consequences. In 1943, Lemkin published Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, which included his definition of genocide. The international community recognized Lemkin’s definition and used it in legal arguments during the Nuremberg Trials following WWII. These trials prosecuted and sentenced military officers and personnel for war crimes committed during the Holocaust.

At the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948), the UN ratified its first human rights treaty. They defined genocide as:

“any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Hitler’s Dehumanization Campaign

During the Holocaust of WWII, millions of people were arrested, imprisoned, tortured, mutilated, and murdered because Germany’s Führer Adolph Hitler, labeled them social undesirables. These social outcasts included people who were Jewish, gypsies, disabled, and lesbian-gay-transsexual-queer (LGBTQ), political opponents, and union members. The Jewish ethnic group was Hitler’s primary target; seven out of every ten European Jews died during WWII.

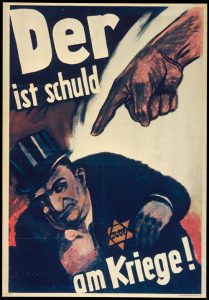

Credit: Bundesarchiv Koblenz (Plak 003-020-020), United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Fair Use of copyrighted material. https://www.ushmm.org/propaganda/archive/poster-guilty-war/.

What historical, social, economic, or political context set this genocide into motion? Following WWI, Germany, along with the rest of Europe and Russia, was straining to recover its balance. As Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power, they focused their efforts on dehumanizing the Jews, portraying them as parasites and vermin that were the root cause of Germany’s struggles. After being elected Chancellor in 1933, Hitler passed legislation that banned Jews from specific jobs, such as teaching, legal work, military positions, accounting, and news media. Nazi propaganda such as the film, “The Eternal Jew,” scathingly criticized Jews for not contributing to society. Hitler enacted laws defining Jews and Aryans in order to exclude Jews from German citizenship. Jews were required to carry passports, denied access to healthcare, and prohibited from marrying non-Jewish people.

Meanwhile, the Nazi Party controlled all aspects of life for German citizens through propaganda and force. Hitler conscripted young Germans into the Hitler Youth, a movement aimed to ensure continuous support of his ideals of Aryan purity and supremacy. It is estimated that by 1935, nearly 60% of German boys were members of the organization.

The Rwanda Genocide

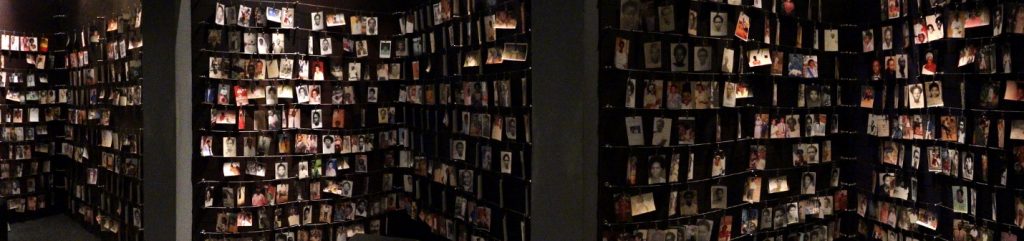

Credit: Adam Jones, Ph.D. Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adam_jones/7654918712/in/album-72157630785425198/.

Beginning in April 1994, Rwanda experienced a genocide that lasted approximately 100 days. The mass atrocities took the lives of almost one million people, left 500,000 children orphaned, and widowed 400,000 women. 130,000 people suspected of committing crimes of genocide were arrested and sent to prison. In the aftermath, an estimated 1.6 million people were displaced from their home regions.

The origins of this genocide lie in social differences and historical conflicts between two major ethnic groups, the Hutu and Tutsi. In the 15th century, Tutsi society was based on raising cattle and Hutu society on raising crops. The Tutsi represented the ruling class socially and minority in population numbers. The two groups co-existed in a feudal economic and social system that shared a common language and accepted intermarriage.

In 1886, the Germans annexed and colonized the region containing modern Rwanda and Burundi. In 1919, they ceded the region to Belgium. The European colonizers categorized their African subjects by racial characteristics, dividing the Tutsi and Hutu into light-skinned and dark-skinned groups, respectively. The Tutsi were accorded the rights and privileges of a superior, light-skinned race. The Hutu were no longer allowed social mobility via occupation or marriage, cementing their lower-class status. Identification cards ensured preferential treatment for Tutsis over Hutus.

Rwanda became an independent nation in 1961, following a social revolution instigated by the Hutu-led by Parti du Mouvement de l’Émancipation Hutu (PARMEHUTU). The new government consisted of only Hutu officials. What followed was a civil war, during which an estimated 20,000 Tutsi died, and another 150,000 fled or were exiled.

By the late 1980s, Tutsi refugees in Uganda had organized into a political and military organization, the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF). In 1990, the Tutsi-led RPF invaded Rwanda to restore their place within the nation. In addition to staging armed resistance to the invaders, the incumbent Hutu used the journal Kangura, to spread propaganda designed to incite public disdain for the Tutsi.

In 1993, the two sides signed the Arusha Accords, a UN-sponsored agreement to end the civil war and create a transitional, coalition government. Decades of institutional hatred made it difficult for many Hutu to embrace the agreement and negotiations for installing the new government dragged.

On April 6, 1994, the airplane carrying Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundi President Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down and the two men were killed. Both presidents were Hutu. Tutsi and Hutu accused each other of the incident. Almost immediately, extremist Hutu leaders launched a campaign against the country’s Tutsi and moderate Hutu. In 100 days, 800,000 people died. Hundreds of thousands of women were raped. According to the UN, “By October 1994…out of a population of 7.9 million, at least half a million people had been killed. Some 2 million had fled to other countries and as many as 2 million people were internally displaced.”

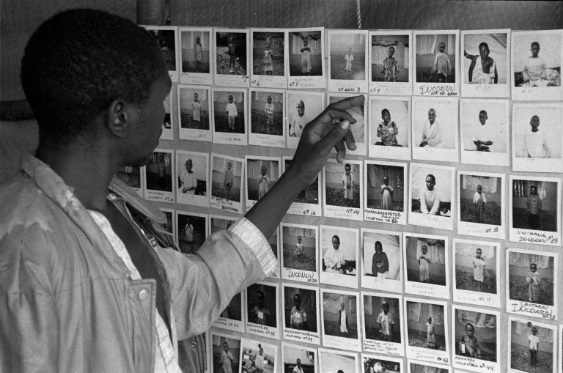

Credit: Benno Neeleman, British Red Cross. Flickr. CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/britishredcross/9082110405.

The genocide ended in July 1994, when the RPF forcibly overthrew the Hutu-led government. Rwanda was in smoldering ruins, with hundreds of thousands of survivors traumatized, its infrastructure demolished, and over 100,000 accused perpetrators imprisoned. Furthermore, the upheaval destabilized all of central Africa. In 1996, the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo turned into a battleground between remaining Hutu extremists and the newly established government.

Justice, accountability, unity, and reconciliation have been elusive for Rwandans. On April 25, 1998, 22 people convicted of participating in the genocide were publicly executed in Rwanda. The human-rights watch group Amnesty International declared the executions devalued human life and expressed concerns that the accused did not receive fair trials. Human Rights Watch reported that many of the accused were tried in groups and not provided with legal assistance. In 2007, Rwanda abolished the death penalty.

As demonstrated in Rwanda, the repercussions of genocide have vast and long-lasting effects. In addition to spotlighting the participants involved, scrutiny is directed at other countries and their responsibility to intervene.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- Do countries have an ethical responsibility to intervene in a genocide taking place in another country? What is the responsibility of an individual?

- Should a nation seek external help from other countries to deal with genocide? What type of help should they receive?

- Genocides have not decreased following the Holocaust, which begs the question, who is responsible for protecting ethnic groups from being targeted and persecuted?

- Do you think that capital punishment or execution is an acceptable punishment for crimes against humanity, such as genocide?

When Good People Commit Evil Acts

“All humans are human. There are no humans more human than others. That’s it.”—Roméo Dallaire, UN peacekeeping commander.

So, what makes people turn a blind eye to the sufferings of others in certain circumstances and offer help in abundance in others? This section explores moral, social, and psychological factors that could lead people to commit themor allow them to happen. Bear in mind that there are no easy answers as to why mass atrocities happen, and the explanations that follow provide food for thought more than they do solutions.

Moral Rationalization

In a fundamental sense, people tend to use their choices to validate their morality, rather than the other way around. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt believes morality is an inseparable part of human nature that creates group solidarity. Haidt explains that our “groupish nature” is prone to moral rationalization, “begin with the conclusion, coughed up by an unconscious emotion, and then work backward to a plausible justification.” He adds that group unity is morally neutral; it can drive good acts such as heroism or evil acts such as genocide.

The Milgram Experiment

Psychologist Stanley Milgram was the son of Jewish Europeans who had survived Nazi prison camps. He was fascinated when Nuremberg Trial defendant Adolf Eichmann, who, when asked to justify organizing the Holocaust, offered the defense, “I was just following orders.”

Credit: Stanley Milgram. Jeroem Busscher, narrator. “Psychologie van het beïnvloeden: Milgram experiment.” DenkProducties. YouTube. Fair Use of worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to access content. https://youtu.be/yr5cjyokVUs

Milgram developed a famous experiment to investigate how people can be ordered into harming another person. Researchers instructed test subjects to administer an electric shock to another person every time that person incorrectly answered a question. The intensity of the shock increased after every incorrect answer. If the test subject hesitated, researchers verbally prompted them to keep administering shocks. The test subject could voluntarily refuse to stop at any time; verbal instructions were the only thing compelling them to continue.

Out of 40 test subjects, only 14 defied verbal instructions at some point and refused to administer any more shocks. What the test subjects did not know was that the entire quiz was rigged. No shocks were ever administered. The person answering questions would deliberately get them wrong and act like they were in pain.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Do you think you would be susceptible to mind control?

The Lucifer Effect

Philip Zimbardo researched the psychology of human behavior in what is now known as the Stanford Prison Experiment. 24 young men were screened for physical and mental health. They were assigned to one of two role-play groups, guards or prisoners, and placed in a simulated prison. As a precaution, guards could not physically abuse prisoners. The experiment was scheduled to last two weeks; however, Zimbardo terminated the study in six days:

“Within 36 hours, the first normal, healthy student prisoner had a breakdown. … We released a prisoner each day for the next five days, until we ended the experiment at six days, because it was out of control. There was no way to control the guards.”

Zimbardo calls this behavior the Lucifer Effect, which is when a person crosses the boundary between good and evil actions. He explains the prison environment dehumanizes everyone in it, spawning conditions that can induce a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde transformation in an otherwise psychologically healthy person.

Free Will versus Situational Psychology

The experiments of Milgram and Zimbardo highlight the power of situational psychology to influence people’s behavior. Sources of situational psychology can include peer pressure, social conformity, fashion trends, or authority figures.

Situational psychology can coerce people into complying with the group consensus.

Credit: “Question the Herd | Brain Games.” National Geographic. YouTube. Fair Use of worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to access content. https://youtu.be/0IJCXXTMrv8.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Have you ever bought an item or attended an event because of an advertisement?

- Have you said or done something because friends or family influenced you?

The Anchor Factor

British illusionist and mentalist Derren Brown tested his powers of persuasion in the television series, The Heist (2006). Using the cover of a motivational seminar, Brown persuaded people to commit what they believed was an armed robbery. The volunteers were average, law-abiding citizens with no record of crime or violence.

Among the human tendencies Brown exploited was anchoring, which is a bias in decision-making that disproportionately favors of one piece of information, the anchor. Once the bias is set, the anchor becomes the basis for all other decisions that follow. Brown anchored feelings of invulnerability, euphoria, and aggression to audio and visual cues, such as a color, song, and clothing. Along with other psychological tools, Brown used the anchoring cues to skillfully manipulate his unsuspecting participants into “stealing” £100,000 ($127,340) from a uniformed security guard using a realistic-looking fake gun.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- What influences our decisions in terms of the stance we take regarding human rights and global issues?

Bystander Effect: Passing the Buck

The bystander effect occurs when someone fails to intervene or help another person in distress or need of aid. The effect is more likely to happen when other people are present to witness the scene. In fact, the more witnesses there are, the less likely it is that anyone will take action to help. Even when faced with a victim in extreme danger, a person on the scene is much less likely to intervene if they perceive other people are present.

The term bystander effect became famous following the murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens, New York, on March 13, 1964. According to The New York Times story published two weeks later, 38 people heard or saw Genovese being assaulted and stabbed on the street that evening. None of the 38 witnesses intervened or called the police during the 30-minute attack. Only one witness called the police after Genovese had died.

Some countries have laws that require bystanders to intervene in certain situations. Three people in Germany were charged and fined for deliberately ignoring an 83-year-old-man who had fallen and hit his head. The man later died.

Tom Williams of Utah Public Radio interviews Dr. Guiora about his connection to and work on the bystander effect.

Credit: Dr. Amos Guiora, Tom Williams. “‘The Crime Of Complicity: The Bystander In The Holocaust’ With Amos Guiora On Access Utah.” Access Utah, Utah Public Radio. Fair Use of copyrighted material. https://www.upr.org/post/crime-complicity-bystander-holocaust-amos-guiora-access-utah.

Dr. Amos N. Guiora is a law professor at the University of Utah and former Lt. Colonel in the Israeli Defense Force. Dr. Guiora is a noted counter-terrorism expert who has extensively researched the bystander effect during the Holocaust and in contemporary sexual assault cases. Part of his motivation comes from the experiences of his parents and relatives during the Holocaust. In addition to teaching and conducting research, he lobbies to enact bystander laws in Utah.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Have you ever held back from speaking or acting because you were afraid of what other people watching you might think?

From Accepting Responsibility to Taking Action

In 1948, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide adopted the legal definition of genocide. By 2019, 154 countries promised “never again” to the crime of genocide. The convention provides a legal imperative for intervention when genocide occurs. But acting on this promise has been less successful. An article in the magazine Spiegel International estimates 37 genocides have occurred between 1945-2005, including in countries that ratified the convention: Bangladesh (ratified in 1998), Guatemala (1950), Bosnia(1992), Cambodia (1950), and Rwanda (1975).

The Call for Human Rights

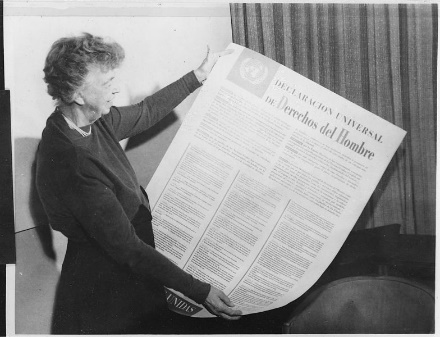

Credit: National Archives and Records Administration. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eleanor_Roosevelt_and_United_Nations_Universal_Declaration_of_Human_Rights_in_Spanish_09-2456M_original.jpg

The UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) defines the universality of human rights. Since 1948, countries around the world have reiterated the call for human rights. The first two articles of the declaration read:

“1. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

“2. Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.”

Remembering Our Collective Humanity

Individuals express their personal feelings, opinions, and experiences through various media such as visual art, music, literature, performance, and more. By sharing and engaging with these individual stories, we create a community of shared experiences that transcends political and cultural boundaries. This bond forms our collective humanity, which has the potential to elicit change, enforce justice, heal trauma, and empower others (and ourselves).

The vivid verse of Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man reinforces the idea that humanity must not forget what others have suffered. To be silent is akin to being complicit in the crimes of others. Levi, an Italian-Jewish chemist, was a prisoner in Auschwitz. The unspeakable horrors he witnessed left him emotionally and physically wounded.

African-American poet Maya Angelou celebrates her identity in the face of prejudice and injustice in the poem Still I Rise. Angelou portrays her tenacious spirit, which endures in the face of institutional and personal criticism. She challenges the reader to accept who she is because she has already accepted herself.

Finding Hope through the Humanities

The humanities may not be able to provide all the answers or offer definitive explanations for the seemingly inexplicable horrors. However, they certainly provide a foundation for establishing positive human relations around the globe. By articulating resilience in the face of oppression and brutality, the humanities can cultivate public awareness. Shining a spotlight on hope is arguably the first step redressing the imbalance of equity on a global stage.

In his opinion piece “Scrooges of the World, Begone!” New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof cautions against falling into an endless tirade of bad news. Too many negative stories create a self-fulfilling spiral of adverse reactions that are particularly damaging for developing nations.

“Unfortunately, bad news is news, and good news isn’t. We cover planes that crash, not those that take off. But a relentless focus on bad news unfortunately leads people to conclude that places from Haiti to Congo are hopeless, driving away tourists, investors and donors. So, at least once a year, it’s worth stepping back and acknowledging progress.”

Irish poet and Nobel Peace Prize (1995) winner Seamus Heaney wrote The Cure at Troy to criticize South African apartheid and honor Nelson Mandela. He begins by describing the suffering of human beings. After acknowledging the shortcomings of bearing witness through words, Heaney concludes on a bright note of hope:

Call miracle self-healing:

The utter, self-revealing

Double-take of feeling.

If there’s fire on the mountain

Or lightning and storm

And a god speaks from the sky

That means someone is hearing

The outcry and the birth-cry

Of new life at its term.

In Salt Lake City, Utah Humanities sponsors a free, accredited, college-level humanities course for those “of modest means who dare to dream.” Offered at three partner colleges, the Venture Course teaches philosophy, art history, literature, and American history. Students also learn how to apply critical writing and thinking. Course organizers discovered that studying the humanities gave people the confidence to improve their lives, contribute to society, appreciate the value of education, and expand their goals. Course co-founder Jean Cheney explains the importance of teaching humanities:

“I see the humanities having a resurgence as more and more of us, in all walks of life, recognize that critical thinking, the ability to read and communicate well, and a deep understanding of our nation’s values, history and government are essential if our democracy is to survive. The humanities are not ‘nice to haves’ and peripheral to a sound education or a well-lived life. They are its heart.”

Calculating the Value of Human Life

Most private and government health insurers use a formula to estimate the value of one human life, roughly $50,000 per year. Insurers use this value to decide whether a medical procedure should be covered, i.e., is the cost of the procedure worth the cost of saving a person’s life. Independent research indicates that annual figures of $129,000 and $183,000-$264,000 are more accurate.

Questions to Critical & Creative Thinking

- What do you think about these figures? Do you think they accurately reflect the value of human life? Why or why not?

- Can you devise additional criteria for assessing the material value (currency) of human life?

- Can you think of non-material (intangible) factors that should be considered when assessing the value of human life?

The humanities examine the value of human life from perspectives not centered around dollars and cents. As you might expect, different cultures have very different ways to assess a person’s value. Many religions have specific guidelines about the value of human life, such as the Ten Commandments of Christianity or the doctrines of ahimsa (non-injury) and samsara (cycle of life) in Hinduism and Buddhism. Assessing the value of human life can be controversial and challenging. For example, consider the ongoing debates over abortion rights, capital punishment, and assisted suicide. There is also the question of whether the quality of a person’s life is more important than prolonging it.

These challenges are reflected across history. Time and again, people reveal confusingly inconsistent attitudes about the value of human life. There are instances when they do everything possible, including sacrificing themselves, to preserve other people’s lives. Other times, such as in genocide, people rationalize why they maliciously devalue, injure, and murder others. When the bystander effect takes hold, people become indifferent to the endangerment of another person.

Credit: Al3xanderD. Pixabay. Free for commercial use. No attribution required. https://pixabay.com/photos/corona-virus-pandemic-covid-19-5002332/.

How we view ourselves and the world impacts our decisions about who has a right to life and who does not. The debate in the United States over wearing a face mask during the COVID-19 pandemic is an excellent example of how our decision-making is influenced by personal biases. On July 14, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control confirmed “that cloth face coverings help prevent people who have COVID-19 from spreading the virus to others.”

In June 2020, The New York Times reported that among Americans, a person’s gender, political affiliation, and education level are better predictors of whether someone dons a face mask. A Marketwatch article points to the group unity theory of why people refuse to wear face masks. “Those who choose not to wear masks may feel a sense of solidarity, like they’re taking a stand against authority.”

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- When you learn of a catastrophe happening in your home country, do you try to find out what city? Do you contact your relatives?

- Would you be as interested in the news if you learned it had happened 800 miles (1,288 km) away from your hometown?

- Are you opposed to wearing a face mask? Why or why not?

- Do you feel face mask policies infringe on your personal liberty?

All Men Are Created Equal*?

*From the United States Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776).

The United States and the UN agree that human rights are universal and egalitarian, centered around the assumption that all human lives have equal value. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines egalitarianism as:

“1) a belief in human equality, especially with respect to social, political, and economic affairs.”

“2) a social philosophy advocating the removal of inequalities among people.”

It is important to remember that egalitarianism is a modern concept. Historically, people much more commonly believed it was natural for some humans to be superior to others, which also meant enjoying privileges, esteem, and wealth. These roles were not always fixed, but inherent in them was the belief that the superior person had more rights than the inferior one. And this idea of unequal rights informs the definition and practice of social justice.

The Chinese philosopher Confucius proposed that the hierarchy of Heaven→Man served as the universal model for all human relationships, such as ruler→subject, father→son, or teacher→student. He asserted that by aligning ourselves with the natural order of the universe, we are assured of social harmony, moral governance, and economic stability. The superior man is assumed to be a virtuous one, with a moral obligation to treat his inferiors justly. This assumption meant that quite often, justice was whatever authority figures deemed correct.

Greek philosophers also proposed that some lives have more value than others. Aristotle held the idea that some people were natural slaves; some were natural masters. He also believed women to be naturally inferior to men. Plato, likewise, endorsed the idea that men are naturally superior to women, and some men are superior to everyone. He argued that justice is self-interest enforced by superior strength (might makes right).

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

It could be said that the argument for some humans being superior to others comes from people seeking to bolster their position of power in society, religion, or government.

- Do you agree with this argument? Can you describe an example when the superiority argument was not attached to self-serving motives?

- How do you think the perception of a person’s value might influence the bystander effect? I.e., do you think people are more likely to help someone who looks important or wealthy? (After answering this question, watch a video on the bystander effect.)

- Has anything you read changed your mind about the value of human life? Is your definition conditional, based on individual circumstances?

The Continuum of intervention

Credit: Samantha Power. “A Problem from Hell: Samantha Power Talks about Genocide.” Facing History and Ourselves. YouTube. Fair Use of worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to access content. https://youtu.be/nzxyFIbDWGU/.

Samantha Power, former war correspondent and United States ambassador to the UN, reminds us that intervention is not just military action. She emphasizes that responses to human rights abuses can and should be incremental. Initial actions should be non-violent measures such as diplomatic measures and economic sanctions. “Sending in the Marines” is the last resort.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- How might the suggestions offered in the video been applied to the Holocaust or Rwandan genocide?

- Do you think one of these non-military responses would have made a difference?

The Responsibility to Protect

In 1919, German scholar Max Weber delivered a speech called “Politics as a Vocation.” In it, he claimed that politics is a balancing act between two sets of moral values: the ethic of conviction/attitude (gesinnungsethik) and the ethic of responsibility (verantwortungsethik). The ethic of conviction (the mental attitude, not the court ruling) compels us to act because it is the moral thing to do. The ethic of responsibility compels us to act because it will result in positive or desirable consequences. In other words, do we attempt to stop human suffering because our sense of morality compels us or because we are legally required to comply?

In 2005, the UN adopted an international standard for protecting human rights named The Responsibility to Protect (R2P). The standard establishes a global responsibility to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. R2P consists of three pillars of responsibility:

“Pillar One: Every state has the Responsibility to Protect its populations from four mass atrocity crimes: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing.”

“Pillar Two: The wider international community has the responsibility to encourage and assist individual states in meeting that responsibility.”

“Pillar Three: If a state is manifestly failing to protect its populations, the international community must be prepared to take appropriate collective action, in a timely and decisive manner and in accordance with the UN Charter.”

Pillars one and two express the ethic of conviction. Nations are morally obligated to protect their people from mass atrocities, as well as reach out to other nations during their times of crisis. Pillar three expresses the ethic of responsibility, declaring that there must be consequences for nations that fail to protect their people from mass atrocities.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- R2P was created partially in response to the Rwandan genocide. Looking at the continuum of intervention and the three pillars, how might the Rwandan government have prevented the start of or reduced the impact of genocide?

- How well did other nations follow the three pillars in their responses to the Rwanda genocide?

Human Rights in the Age of Globalization

The term globalization was first used in 1930 to describe an all-encompassing view of education rather than an exchange of ideas across national or physical boundaries. Later, usages of the term in economics more closely resembled the modern meaning. In 1968 globalization was defined as a network of interdependent political organizations around the world. Since then, the concept of globalization has widened to include the exchange and integration of products, culture, ideas, institutions, technology, services, people, and even plants and animals.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 is an example of how modern globalization, in this case, air travel and crowded urban environments, effectively shrinks the distance between countries. The first cases were observed in China on December 31, 2019. By March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization announced the disease had become a pandemic. By comparison, in 1918, influenza first detected in the United States took six months to reach pandemic status. Contributing to the worldwide spread of the disease was WWI, which sent thousands of American troops abroad, crowded together for weeks on military transport ships.

Especially in our present-day age of digital and wireless communication, globalization has removed many traditional barriers between countries and cultures. With this increased awareness of our global society, of course, comes a heightened responsibility to address its most severe problems, such as overpopulation, climate change, food shortages, natural disasters, and pandemics.

Credit: geralty. Pixabay. Free for commercial use. No attribution required. https://pixabay.com/photos/handshake-hands-laptop-monitor-3382503/.

Globalization has built a worldwide interdependence that benefits us in many ways, even contributing to peace and stability through the continuous, live monitoring of world events. International peacekeeping agencies, such as the UN, now have the technology to extend their efforts into most remote corners of the world. Globalization in the humanities means people around the world can create an interconnected community without borders. They can share experiences with people they might otherwise never realized existed. They can organize and collaborate to address our most pressing issues.