East Asia

2.5 China’s Periphery

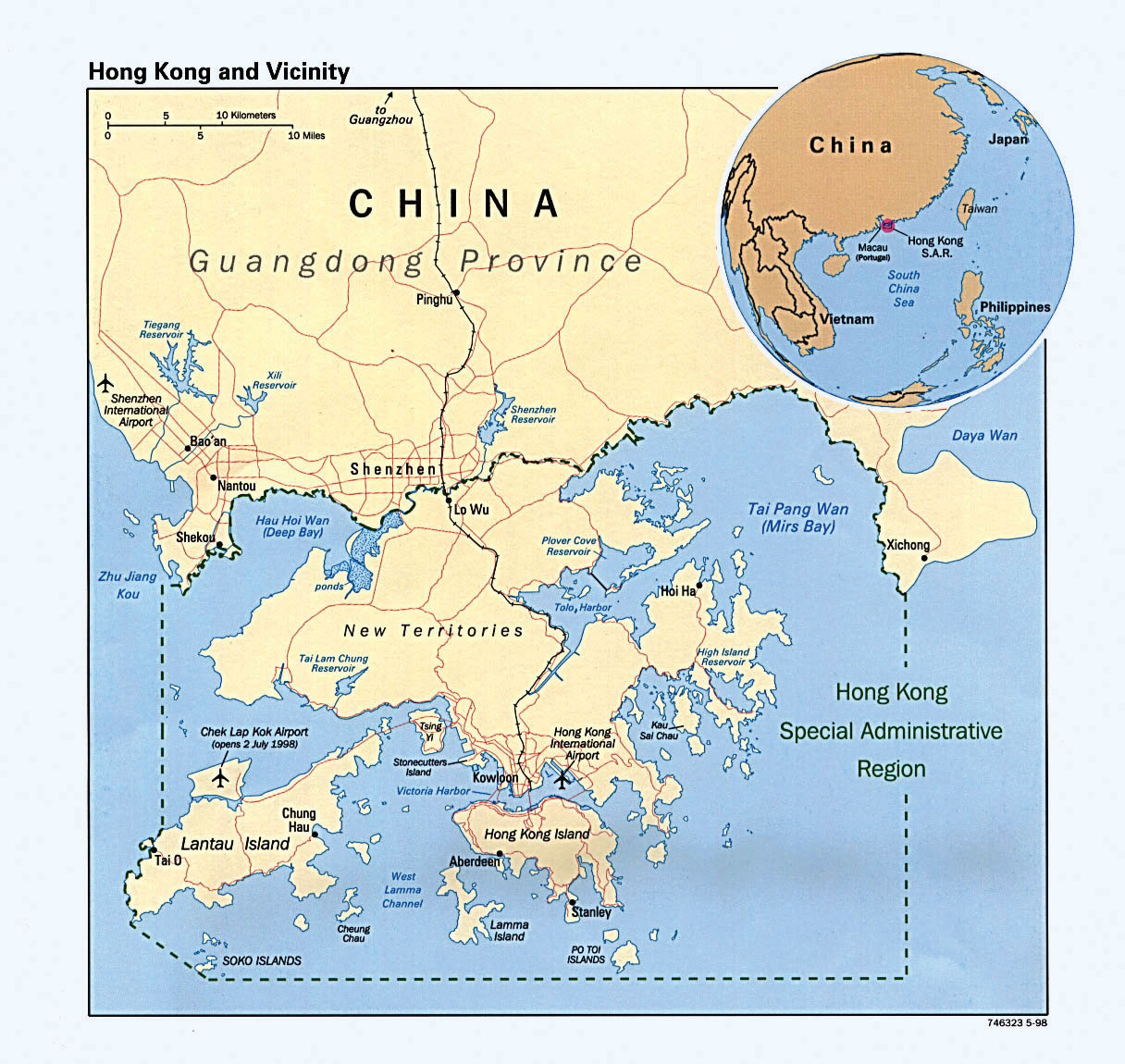

Hong Kong and Shenzhen

Hong Kong, a Special Administrative Region of China, is a city of striking contrasts and mesmerizing beauty. Nestled on the southern coast of China, it is renowned for its towering skyscrapers, bustling harbor, and scenic vistas. It is a unique fusion of Eastern and Western cultures, evident in its architecture, cuisine, and lifestyle. The city’s skyline, dominated by modern skyscrapers, is in harmony with traditional temples and colonial-era buildings.

Climate, Environment, and Physical Landscape

Hong Kong seamlessly blends urban sophistication with natural beauty, offering lush mountains, serene waters, and picturesque islands that provide ample opportunities for outdoor activities like hiking and boating. Its subtropical climate brings hot, humid summers accompanied by typhoons, while winters remain mild and dry. Autumn and spring are the most comfortable seasons, ideal for enjoying the city’s diverse environment. Despite its dense population, Hong Kong dedicates over 40 percent of its land to country parks and nature reserves, preserving biodiversity while providing residents and visitors with tranquil green spaces.

However, the city faces several environmental challenges, including air pollution caused by vehicle emissions and industrial activities, waste management difficulties due to limited landfill space, and water pollution impacting marine ecosystems. Additionally, its hilly terrain makes it vulnerable to natural disasters such as typhoons and heavy rainfall, which can lead to flooding and landslides. Efforts to combat these issues include stricter environmental regulations, public awareness initiatives, and investments in green technology. Striking a balance between development and sustainability remains an ongoing challenge. Still, Hong Kong’s unique physical landscape continues to define its remarkable character, from towering skyscrapers to pristine beaches and islands.

Historical Relationship Between Hong Kong and Mainland China

During World War II, Hong Kong fell to Japanese forces after the Battle of Hong Kong in December 1941, beginning a period of occupation that lasted until Japan’s surrender in 1945. Following the war, Britain resumed control, and Hong Kong entered a phase of rapid economic growth. The city transformed from a trading port into a thriving industrial and financial center, attracting migrants and businesses from mainland China and beyond. This economic boom led to significant infrastructure improvements and improved overall living standards.

As the end of the 99-year lease on the New Territories approached, Britain and China entered negotiations, culminating in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. The agreement outlined that Hong Kong would be handed over to China in 1997 under the “one country, two systems” principle, allowing it to retain its capitalist economy and way of life for 50 years. Since the handover, Hong Kong has maintained autonomy in its legal and economic systems, but tensions have arisen regarding democratic freedoms. The 2019 protests against the extradition bill, which evolved into broader calls for democracy and police accountability, reflected the ongoing complexities between Hong Kong and the Chinese government.

Political Landscape

Hong Kong’s political landscape has significantly transformed from its colonial past to the present. British rule lasted for over 150 years, beginning with the cession of Hong Kong Island in 1842 and expanding with the lease of the New Territories in 1898. Following World War II, Hong Kong experienced rapid economic growth, evolving from a trading port into a thriving financial and industrial hub. Increased prosperity and modernization set the stage for discussions on the city’s future governance.

The 1997 handover marked a turning point. Hong Kong became China’s Special Administrative Region (SAR) under the “one country, two systems” framework, allowing it to maintain its capitalist economy and autonomy for 50 years. However, post-handover tensions emerged, especially regarding democratic freedoms and governance. A particularly significant shift occurred with Beijing’s enactment of the National Security Law in 2020, which criminalized secession and subversion while granting mainland authorities broader powers in Hong Kong. Many viewed this law as threatening the city’s autonomy and freedoms, leading to widespread protests.

Beijing’s response included mass arrests and a crackdown on pro-democracy activists, media, and educational institutions, contributing to a climate of political suppression. Despite these measures, many Hongkongers continue to express their aspirations for democracy and autonomy. Moving forward, Hong Kong faces the challenge of balancing its autonomy within the “one country, two systems” framework while navigating increasing scrutiny from Beijing. The ongoing tension between democratic ambitions and central government control will likely remain a source of political instability.

Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s cultural heritage is a fusion of Eastern and Western influences, shaped by its history as a British colony and its status as a Special Administrative Region of China. From its early fishing villages to British governance, the city evolved into a global metropolis while retaining its distinct traditions. Vibrant festivals such as Lunar New Year and the Dragon Boat Festival coexist with colonial-era celebrations like Christmas. The city’s architecture reflects its layered past, featuring colonial landmarks, traditional Chinese temples, and preserved fishing villages. Culinary traditions blend Cantonese specialties like dim sum with British-influenced treats such as egg tarts, making Hong Kong a “Gourmet Paradise.”

Beyond cuisine and architecture, Hong Kong remains a hub for arts and literature, with institutions like the Hong Kong Museum of History and West Kowloon Cultural District preserving its rich heritage. Cantonese is dominant, though English and other dialects highlight its global character. Despite political shifts, Hong Kong’s cultural identity continues to thrive, ensuring its resilience and uniqueness as it navigates the future.

Economic Developments and Challenges

Hong Kong has evolved from a modest fishing village into a global financial powerhouse. Established as a British colony in 1841, its deep-water harbor quickly became a focal point for maritime trade. The city’s economy grew through early trade activities, facilitating exchanges between China and the world. The founding of HSBC in 1865 laid the groundwork for a strong banking sector, reinforcing Hong Kong’s role as an essential financial center in Asia.

Following World War II, Hong Kong experienced rapid industrialization, driven by an influx of refugees from mainland China. The city became an export-oriented hub, producing goods such as textiles and electronics for global markets. By the 1970s and 1980s, Hong Kong transitioned from manufacturing to a service-based economy, with finance, business services, tourism, and real estate becoming dominant sectors. Modern infrastructure and an expanding stock market established its reputation as a leading economic center.

The 1997 handover from British to Chinese sovereignty solidified Hong Kong’s position under the “one country, two systems” framework, ensuring the continuity of its capitalist economy and legal systems. In the decades since, Hong Kong has maintained its status as a premier financial hub, attracting multinational corporations with its low taxation and free-market policies. Tourism also plays a significant role in its economy, with attractions like Victoria Peak, bustling markets, and theme parks drawing millions of visitors annually.

Looking ahead, Hong Kong faces challenges such as political unrest, economic pressures from mainland China, and environmental sustainability concerns. However, the city continues to embrace innovation, investing in fintech, biotech, and smart city technologies. Economic integration through the Greater Bay Area initiative presents new opportunities, ensuring Hong Kong remains a vital link between China and the global market. Its resilience and adaptability determine its future as a dynamic and influential economic force.

Urban Development

As a densely populated urban center, Hong Kong faces significant environmental and urban development challenges. These include managing air and water quality, addressing the impacts of climate change, and ensuring sustainable urban planning and development. The city’s ability to balance economic growth with environmental sustainability will provide its residents with a high quality of life. Additionally, the need for affordable housing and the efficient use of limited land resources will continue to be pressing issues.

During the 1990s, as China actively invested in its industrial sector, it sought ways to attract the business generated by Taiwan and Hong Kong, two economic tigers. An opportunity came in 1997 when the ninety-nine-year lease of the New Territories to Britain expired. China did not want to renew the lease, so a deal covering all of Hong Kong was struck between China and Great Britain. Britain would relinquish all its claims to Victoria, the port, and all of Hong Kong if China would allow the area to remain non-Communist and under its autonomy for fifty more years. China agreed, and Britain left Hong Kong in 1997. Hong Kong became associated with mainland China as a unique autonomous region, but remained capitalist and democratic in its operations. The autonomy was supposed to last until July 1, 2047. This opened the door for Taiwan and other trading partners to increase trade with China through Hong Kong.

Shenzhen, a special economic zone (SEZ) across the border from Hong Kong in China, was ready to capitalize on its accessibility to the port and the enormous trade that Hong Kong had established. Shenzhen became one of the fastest-growing cities globally and a manufacturing and trade center for the global economy. It grew from a moderately sized city of about three hundred fifty thousand in the early 1980s to a city of over 12.5 million by 2020. Shenzhen has established its port and is a magnet for international trade.

More than 95 percent of the 7.5 million people living in Hong Kong are ethnically Chinese. The people have strong ties to mainland China, but highly value their separate and independent economic and political status. Hong Kong is a major financial and banking center for Asia and has been working with the Chinese government to provide private banking services for Chinese citizens. The small land size of Hong Kong makes it a high-priced real estate destination. The cost of living is high, and space is at a premium and expensive.

Nevertheless, Hong Kong attracts millions of visitors annually and has established itself as a tourism hub for people desiring to visit southern China. Tens of millions of tourists each year use Hong Kong as a base or stopover point to enter China’s southern provinces. Hong Kong offers visitors immense shopping possibilities in a safe and modern environment, which is attractive to people worldwide. Cantonese is the official language, but English is widely spoken in Hong Kong because of Britain’s influence and because of world trade relationships.

Across the Pearl River Estuary to the west is the former Portuguese colony of Macau. The arrangement between China and the British government over Hong Kong provided a pattern that was also applied to Macau. At the end of 1999, Portugal relinquished its claim to Macau, and the colony was turned over to the Chinese government under an agreement similar to the agreement between Britain and China regarding Hong Kong. Macau was enabled to retain its autonomy and free-market economy for fifty years as it became a unique administrative region (SAR) of China. Macau is a much smaller territory than Hong Kong, with only about half a million residents.

National Security Law

The question of identity is central to Hong Kong’s future. The city’s unique blend of Eastern and Western traditions has long defined its character. However, the increasing influence of mainland China raises concerns about preserving this distinct identity. The challenge will be to navigate this integration while maintaining the cultural and social uniqueness that distinguishes Hong Kong from other Chinese cities. This will also involve addressing the generational divide, as younger Hongkongers who have grown up with a strong sense of local identity may resist efforts to align more closely with mainland China.

Recently, Beijing has implemented measures to tighten its control over Hong Kong. The National Security Law enacted in 2020 has been a significant point of contention, leading to concerns about the erosion of freedoms and autonomy promised under the “one country, two systems” framework. Despite these challenges, Hong Kong continues to play a vital role as a global financial center and a bridge between East and West.

The National Security Law, enacted by Beijing on June 30, 2020, aims to reinforce China’s control over Hong Kong by criminalizing acts of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. The law allows for the establishment of mainland security agencies in Hong Kong and grants them broad powers to operate with minimal oversight from local authorities. Critics argue that the law undermines the autonomy promised under the “one country, two systems” principle by curtailing freedoms of speech, assembly, and the press. Proponents, however, assert that it is necessary to restore stability and order in the wake of the 2019 protests.

The enactment of the National Security Law on June 30, 2020, sparked widespread protests in Hong Kong. Many citizens took to the streets, decrying the law as an affront to the freedoms and autonomy promised under the “one country, two systems” principle. The law was seen as a tool for Beijing to quash dissent and tighten its grip on the city, criminalizing acts of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. Fearing the loss of their liberties, Protesters rallied in large numbers, demanding the repeal of the law and more significant democratic reforms.

The Chinese government’s response was swift and severe. Authorities conducted mass arrests of activists, lawmakers, and ordinary citizens who were involved in or supported the protests. Prominent pro-democracy figures were charged and imprisoned under the new law, which granted mainland security agencies broad powers to operate with minimal oversight. The crackdown extended to the media and educational institutions, with journalists, teachers, and students targeted for their perceived opposition to the central government.

Beijing’s heavy-handed measures have had a chilling effect on Hong Kong’s once vibrant civil society. Public demonstrations have dwindled in the face of increased surveillance and the threat of harsh penalties. Despite these efforts to suppress dissent, the spirit of resistance remains alive among many Hongkongers, who continue to seek ways to express their aspirations for freedom and democracy in a city that has long stood as a beacon of both.

Taiwan (ROC)

Taiwan, an island nation located off the southeastern coast of China, stands as a beacon of rich history, vibrant culture, and significant economic prowess. Officially known as the Republic of China (ROC), Taiwan has developed a unique identity separate from mainland China despite the ongoing political and diplomatic complexities surrounding its status.

Climate, Environment, and Physical Landscape

Taiwan has a diverse topography, ranging from coastal plains to high mountains. The island’s natural landscape includes the rugged mountains of Taroko Gorge and the serene Sun Moon Lake. Taiwan’s varied ecosystems contribute to its rich biodiversity, housing numerous endemic species of flora and fauna. Efforts to preserve these natural treasures are integral to Taiwan’s environmental policies.

Taiwan’s climate is predominantly subtropical, with hot, humid summers and mild winters, and it is subject to typhoons from June to October, bringing heavy rains and strong winds. The island’s diverse topography, ranging from coastal plains to high mountains, influences regional climate variations. Taiwan’s varied ecosystems support rich biodiversity, including numerous endemic species of flora and fauna, which the government and various organizations actively work to protect from urbanization and industrialization pressures. Taiwan’s stunning natural landscape, featuring rugged mountains like Taroko Gorge and serene spots like Sun Moon Lake, is a key focus of its environmental policies.

Taiwan’s rapid industrialization and urbanization have led to several environmental challenges. Air pollution is a significant concern, especially in urban areas with high vehicle emissions and industrial activities. The island’s topography worsens this issue by trapping pollutants in certain regions, resulting in poor air quality.

Water pollution is another pressing issue, with industrial discharge and agricultural runoff contaminating rivers and coastal waters. The government has taken steps to improve water quality through stricter regulations and investments in wastewater treatment facilities.

Waste management is also challenging due to the island’s limited land area, making landfill options scarce. Taiwan has implemented recycling programs and waste-to-energy initiatives, but the growing volume of waste remains a concern.

Additionally, Taiwan is highly vulnerable to natural disasters. Located on the Pacific Ring of Fire, the island experiences frequent earthquakes that can cause significant damage and threaten infrastructure and human lives. The annual typhoon season also brings heavy rains, flooding, and landslides, particularly in mountainous regions.

The government and various organizations have prioritized policies, technological innovations, and public awareness campaigns to address these environmental issues. Efforts to mitigate the impact of natural disasters include improving building codes, investing in early warning systems, and reinforcing critical infrastructure.

Historical Background

Taiwan’s history spans thousands of years, beginning with its indigenous Austronesian tribes. The island first appeared in recorded history when Portuguese sailors spotted it in the 16th century, naming it “Ilha Formosa” or “Beautiful Island.”

Throughout the 17th century, colonial powers fought for control—first the Dutch in the southwest and the Spanish in the north—until Ming loyalist Koxinga expelled the Dutch in 1662, using Taiwan as a base against the Qing Dynasty. The Qing later annexed Taiwan in 1683, ruling until it was ceded to Japan in 1895. Japanese rule brought modernization and infrastructure improvements, lasting until the end of World War II in 1945.

Post-war, Taiwan was governed by the Republic of China (ROC). After the Chinese Civil War, the ROC government retreated to Taiwan in 1949, when the Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland. Since then, Taiwan has functioned as a separate political entity, although the PRC claims it as part of its territory.

Political Landscape

Taiwan operates as a democratic nation with a multi-party system. Its government is divided into five branches: the Executive Yuan (Executive Branch), Legislative Yuan (Legislature), Judicial Yuan (Judiciary), Examination Yuan (Civil Service), and Control Yuan (Audit and Oversight). The President, elected by popular vote, is the head of state.

Taiwan’s relationship with mainland China is complicated, as Taiwan views itself as sovereign, while China considers it a breakaway province. This dispute affects Taiwan’s international recognition, including its exclusion from the United Nations.

Despite diplomatic challenges, Taiwan engages globally through trade, economics, and cultural exchanges. It maintains unofficial relations with many nations and participates in organizations such as the World Health Organization and World Trade Organization under various designations.

Cultural Heritage

Taiwan is home to various indigenous cultures with distinct languages, traditions, and customs. The government actively works to preserve and promote indigenous heritage as a key part of the island’s national identity. Traditional Chinese customs, Japanese influences, and indigenous practices shape Taiwanese culture. Major festivals such as the Lunar New Year, Dragon Boat Festival, and Mid-Autumn Festival are widely celebrated.

Taipei and other cities serve as vibrant cultural hubs, featuring a thriving arts scene, dynamic nightlife, and landmarks like Taipei 101, night markets, and temples, blending historical and modern influences.

Mandarin Chinese is the official language, but Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and indigenous languages are also spoken, with ongoing efforts to promote linguistic diversity and preserve local dialects.

Economic Development

Taiwan is a global leader in technology and innovation, especially in the semiconductor industry. Companies like the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) play a critical role in the worldwide supply chain, producing advanced microchips for various industries.

Its economy has evolved from agriculture to an industrial powerhouse, with key sectors including electronics, machinery, petrochemicals, and textiles. The government continues investing in renewable energy and biotechnology to enhance economic diversity.

Taiwan’s strategic location makes it a hub for international trade. Through free trade agreements and financial partnerships, Taiwan fosters strong economic ties with nations like the United States, Japan, and the European Union.

Despite challenges such as export dependency, an aging population, and environmental sustainability concerns, Taiwan has opportunities for growth in technological advancement, green energy, and tourism.

Political Tensions with Mainland China

The relationship between Taiwan and Mainland China is fraught with geopolitical tensions rooted in historical, political, and ideological differences. After the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) retreated to Taiwan, establishing the Republic of China (ROC) government, while the Communist Party founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland. Since then, the PRC has considered Taiwan a breakaway province that must eventually be reunified with the mainland by force if necessary.

Taiwan, however, has developed its own distinct political identity and democratic institutions, and many of its citizens consider it a sovereign state. The PRC pressures international organizations and countries not to recognize Taiwan as a separate nation, leading to Taiwan’s limited participation in global forums. Military tensions often escalate, with the PRC conducting military exercises near Taiwan and increasing its naval presence in the Taiwan Strait.

United States Role in Protecting Taiwan

The United States is pivotal in safeguarding Taiwan against external threats, predominantly from Mainland China. The cornerstone of this involvement is the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, which, while stopping short of formally recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation, commits the U.S. to assist Taiwan in maintaining its defense capabilities. This Act ensures that the U.S. provides Taiwan with the necessary military support and arms sales to bolster its self-defense. Furthermore, the U.S. consistently advocates for a peaceful resolution to cross-strait relations, emphasizing dialogue and diplomacy to mitigate military tensions.

The U.S. enforces its commitment to Taiwan’s security through a strategic military presence and regular arms deals. This includes the sale of advanced weaponry and defense systems designed to enhance Taiwan’s deterrence capabilities. The U.S. conducts freedom of navigation operations in the Taiwan Strait to assert the principle of international waters and support Taiwan’s strategic position.

Taiwan’s geopolitical significance, particularly in the technology and semiconductor industries, underpins the U.S. involvement. Ensuring Taiwan’s security is crucial for regional stability and the global economic order. The United States’ protective stance counterbalances China’s assertive posture, maintaining a delicate equilibrium in this volatile region.

These geopolitical tensions impact regional stability and global economic interests, particularly given Taiwan’s critical role in the technology and semiconductor industries. The situation remains a delicate balancing act, with the potential for significant implications depending on how the relations between Taiwan and Mainland China evolve.

Future Challenges for Taiwan

Taiwan faces several key challenges that will shape its future. Economic dependency on exports, particularly in technology and semiconductors, makes it vulnerable to global market shifts and geopolitical tensions, especially with Mainland China.

An aging population presents social and economic concerns, including rising healthcare costs, a shrinking workforce, and pension sustainability, requiring policy reforms and innovative solutions. Environmental sustainability is also a pressing issue, necessitating investment in green energy, carbon reduction, and sustainable practices.

Geopolitical tensions with China threaten Taiwan’s security and sovereignty, making international support and defense strategies critical. Despite these challenges, Taiwan has opportunities in technological innovation, green energy expansion, and tourism, which can drive economic diversification and resilience.

Autonomous Region of Tibet

Tibet, often called the “Roof of the World,” has majestic mountains, a rich cultural heritage, and profound spiritual traditions. Located on the Tibetan Plateau in Central Asia, Tibet boasts breathtaking landscapes, including the towering peaks of the Himalayas, serene lakes, and vast grasslands. The region is known for its unique blend of Buddhist practices, vibrant festivals, and distinctive art, which have been preserved for centuries despite various historical challenges. As Tibet navigates the complexities of modernity and its relationship with Mainland China, its cultural and spiritual legacy continues to inspire and captivate the world.

Climate, Environment, and Physical Landscape

Tibet’s high-altitude climate is cold and dry, with extreme temperature fluctuations between day and night. Winters are long and harsh, while summers are short and mild. Precipitation is limited, except for a brief monsoon season from June to September, which brings rainfall mainly to the southeast.

Environmental challenges include climate change, which is causing glacial retreat and permafrost thawing, which affect water availability and ecosystems. Overgrazing, deforestation, and modernization also threaten biodiversity and traditional ways of life.

Tibet’s landscape is dominated by the vast Tibetan Plateau, known as “the Third Pole” for its extensive ice fields. It is surrounded by towering mountain ranges, including the Himalayas, home to Mount Everest. The northern plains are arid, featuring rolling steppes and scattered lakes, creating a striking contrast between rugged peaks and serene grasslands.

Preserving Tibet’s delicate environment is crucial, as climate change and human activity continue to impact the region. Sustainable efforts are needed to protect its natural heritage and ecological balance.

History of Tibet

Tibet’s history is a rich tapestry shaped by ancient dynasties, religious traditions, and cultural resilience. Before Buddhism arrived in the 7th century, early inhabitants practiced animistic and shamanistic beliefs. The Tibetan Empire’s embrace of Buddhism profoundly influenced its society, governance, and artistic legacy, leading to the construction of iconic monasteries.

During the medieval period, Tibet experienced cycles of unity and fragmentation, often impacted by its powerful neighbors, including China and Mongolia. The 17th century saw the rise of the Dalai Lama’s theocratic government, bringing religious and political stability that allowed Tibetan culture and arts to thrive.

In the 20th century, Tibet was caught between British colonial interests and the growing Chinese Republic. Its incorporation into the People’s Republic of China in 1951 led to major political and social shifts, including the exile of the 14th Dalai Lama in 1959. Today, Tibet balances modernization with preserving its cultural and spiritual identity. The Tibetan people’s resilience remains central to their enduring legacy.

Geopolitical Tensions Between Tibet and China

Historical Background

Tensions between Tibet and mainland China have roots in a complex and turbulent history. In the early 20th century, Tibet was caught between British colonial interests and the rising power of the Chinese Republic. However, the most significant turning point came in 1951, when Tibet was incorporated into the People’s Republic of China. This incorporation led to profound political and social changes within Tibet, including the forced exile of the 14th Dalai Lama to India in 1959.

Political Tensions

The core of the tensions lies in Tibet’s political sovereignty and autonomy. Many Tibetans advocate for greater autonomy or even complete independence from China. The Chinese government, however, maintains that Tibet has been an integral part of China for centuries and strongly opposes any form of separatism. This fundamental disagreement has resulted in numerous protests and uprisings within Tibet, often met with harsh crackdowns by Chinese authorities.

Human Rights Concerns

Human rights organizations have raised concerns over the treatment of Tibetans by Chinese authorities. Reports of arbitrary arrests, detention of political prisoners, and suppression of religious freedoms are widespread. Monasteries, central to Tibetan culture and religion, are closely monitored, and spiritual practices are often restricted. Additionally, there are allegations of torture and ill-treatment of detainees, further fueling the tensions between Tibetans and the Chinese state.

Cultural and Religious Suppression

Another significant source of tension is the suppression of Tibetan culture and religion. Tibetan Buddhism, which is integral to Tibetan identity, faces severe restrictions. The Chinese government attempts to control religious institutions and practices, including appointing religious leaders. The most notable example is the Chinese government’s rejection of the Dalai Lama’s spiritual authority and its imposition of a state-sanctioned Panchen Lama, leading to widespread discontent among Tibetans.

Economic and Social Policies

The Chinese government’s economic and social policies in Tibet have also contributed to the tensions. Large-scale infrastructure projects, such as the construction of railways and highways, have led to an influx of Han Chinese migrants into Tibet. This demographic shift has sparked fears among Tibetans of being marginalized in their land. Furthermore, economic development initiatives often prioritize resource extraction and industrialization, which can disrupt traditional Tibetan livelihoods and exacerbate environmental degradation.

Environmental Concerns

Environmental degradation in Tibet, partly driven by Chinese policies, has become a growing concern. The Tibetan Plateau, known as “the Third Pole,” is experiencing rapid glacial retreat and permafrost thaw due to climate change. Overgrazing, deforestation, and infrastructure development also contribute to soil erosion and habitat loss. These environmental changes threaten the region’s biodiversity and the traditional ways of life of the Tibetan people, adding another layer of tension.

International Reactions

The international community’s responses to the Tibet-China tensions vary. Some countries and human rights organizations have voiced support for Tibetan autonomy and criticized China’s human rights record in the region. However, China exerts considerable global diplomatic and economic influence, making many nations cautious. The Dalai Lama remains a prominent global figure advocating for Tibetan rights, drawing attention to the plight of Tibetans and keeping the issue in the international spotlight.

The tensions between Tibet and mainland China are deeply rooted in historical, political, cultural, and economic factors. The ongoing conflict reflects the complex interplay between the desire for Tibetan autonomy and the Chinese government’s assertion of sovereignty. As Tibet continues to navigate modern challenges, its people’s resilience and commitment to preserving their unique identity remain central to their struggle for recognition and rights.

In recent decades, Tibet has continued to navigate the challenges of modernity while striving to preserve its unique cultural and spiritual identity. The Tibetan people’s resilience and commitment to their heritage remain central to the region’s ongoing story.

Mongolia

Mongolia ranks as the world’s nineteenth-largest country in terms of square miles. Mongolia shares similar geography with much of Kazakhstan, which is the world’s largest land-locked nation; Mongolia is the second largest. Despite Mongolia’s vast land area (slightly smaller than the US state of Alaska or the country of Iran), its population is only about three million, and the government is the least densely populated in the world. Mountains, high plains, and grass-covered steppe cover much of Mongolia, which receives only between four and ten inches of rain annually, usually in snow. The Gobi Desert to the south, extending from southern Mongolia into northern China, receives even less precipitation. Inner Mongolia is a sparsely inhabited autonomous region south of Mongolia that the Chinese government governs.

Mongolia’s modern capital city, Ulan Bator, is home to about one-third of the country’s population and has the coldest average temperature of any world capital. Mongolia’s history includes the vast Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, established in the thirteenth century. The Soviet Union used Mongolia as a buffer state between itself and China. Mongolia’s Communist Party dominated politics until the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s. The current government in Ulan Bator must contend with Mongolia’s position between the two giant economies of Russia and China.

Tibetan Buddhism is the dominant religion in Mongolia and is practiced by about 50 percent of the population. The Communist influence is evident in that approximately 40 percent of the population considers itself nonreligious. Most of the people are of Mongol ethnicity. Today, about 30 percent of the people are still semi-nomadic and migrate seasonally to accommodate good grazing for their livestock. The traditional dwelling is a round yurt that can be constructed at any location selected for the season and disassembled for mobility. Mongolian culture and heritage revolve around a rural agrarian culture relying extensively on horses. Archery, wrestling, and equestrian events are some of the most popular sporting activities.

Mongolia’s economy has traditionally been centered on agriculture, but mining has become a significant economic sector in recent years. Mongolia has abundant mineral resources, such as coal, molybdenum, copper, gold, tin, and tungsten. Being landlocked cuts Mongolia off from the global economy. However, the vast amounts of mineral reserves are in demand by core industrial areas for manufacturing and should boost the poor economic conditions that dominate Mongolia’s economy. China has increased its business presence in Mongolia, drawing Mongolia’s attention away from its former Soviet ally to become a significant trading partner.