6 Background: Chemistry & pH

Chemical Bonds

All elements are most stable when their outermost shell is filled with electrons. This is because it is energetically favorable for atoms to be in that configuration and it makes them stable. However, since not all elements have enough electrons to fill their outermost shells, atoms form chemical bonds with other atoms thereby obtaining the electrons they need to attain a stable electron configuration. When two or more atoms chemically bond with each other, the resultant chemical structure is a molecule or compound. Atoms can form molecules by donating, accepting, or sharing electrons to fill their outer shells.

Covalent Bonds

Atoms can share electrons to form covalent bonds. These bonds are stronger and much more common than ionic bonds in the molecules of living organisms. We commonly find covalent bonds in carbon-based organic molecules, such as our DNA and proteins. We also find covalent bonds in inorganic molecules like H2O, CO2, and O2. The bonds may share one, two, or three pairs of electrons, making single, double, and triple bonds, respectively. The more covalent bonds between two atoms, the stronger their connection. Thus, triple bonds are the strongest.

Forming water molecules provides an example of covalent bonding. Covalent bonds bind the hydrogen and oxygen atoms that combine to form water molecules. The electron from the hydrogen splits its time between the hydrogen atoms’ incomplete outer shell and the oxygen atoms’ incomplete outer shell. To completely fill the oxygen’s outer shell, which has six electrons but which would be more stable with eight, two electrons (one from each hydrogen atom) are needed: hence, the well-known formula H2O. The two elements share the electrons to fill the outer shell of each, making both elements more stable.

Nonpolar Covalent Bonds

There are two types of covalent bonds: polar and nonpolar. Nonpolar covalent bonds form between two atoms of the same element or between different elements that share electrons equally. For example, molecular oxygen (O2) is nonpolar because the electrons distribute equally between the two oxygen atoms.

Methane (CH4) is another example of a molecule formed by nonpolar covalent bonds. Carbon has four electrons in its outermost shell and needs four more to fill it. It obtains these four from four hydrogen atoms, each atom providing one, making a stable outer shell of eight electrons. Carbon and hydrogen do not have the same electronegativity but are similar; thus, nonpolar bonds form. The hydrogen atoms each need one electron for their outermost shell, which is filled when it contains two electrons. These elements share the electrons equally among the carbons and the hydrogen atoms, creating a nonpolar molecule.

Polar Covalent Bonds

In a polar covalent bond, atoms unequally share the electrons, meaning that the shared electrons are attracted more to one nucleus than the other. Because of the unequal electron distribution between the atoms of different elements, one of the atoms will develop a slightly positive (δ+) charge and the other a slightly negative (δ–) charge. This partial charge is an important property of water and accounts for many of its characteristics.

Water is a polar molecule, with the hydrogen atoms acquiring a partial positive charge and the oxygen a partial negative charge. This occurs because the oxygen atom’s nucleus is more attractive to the hydrogen atoms’ electrons than the hydrogen nucleus is to the oxygen’s electrons. Thus, oxygen has a higher electronegativity than hydrogen and the shared electrons spend more time near the oxygen nucleus than the hydrogen atoms’ nucleus, giving the oxygen and hydrogen atoms slightly negative and positive charges, respectively. Partial charges develop when one element is significantly more electronegative than the other, and the charges that these polar bonds generate may then be used to form hydrogen bonds based on the attraction of opposite partial charges. Since macromolecules often have atoms within them that differ in electronegativity, polar bonds are often present in organic molecules.

Ionic Bonds

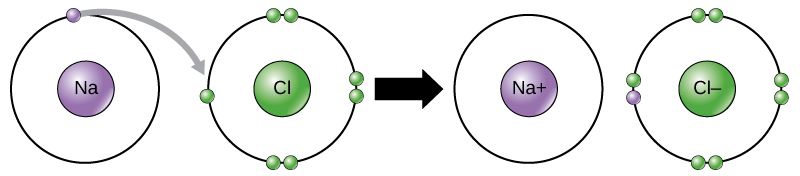

Some atoms are more stable when they gain or lose an electron (or possibly two) and form ions. This fills their outermost electron shell and makes them energetically more stable. Because the number of electrons does not equal the number of protons, each ion has a net charge. Cations are positive ions that form by losing electrons. Negative ions form by gaining electrons, which we call anions. We designate anions by their elemental name and change the ending to “-ide”, thus the anion of chlorine is chloride, and the anion of sulfur is sulfide.

Ions can be formed by electron transfer. For example, sodium (Na) only has one electron in its outer electron shell. It takes less energy for sodium to donate that one electron than it does to accept seven more electrons to fill the outer shell. If sodium loses an electron, it now has 11 protons, 11 neutrons, and only 10 electrons, leaving it with an overall charge of +1. We now refer to it as a sodium ion. Chlorine (Cl) has seven electrons in its outer shell. Again, it is more energy-efficient for chlorine to gain one electron than to lose seven. Therefore, it tends to gain an electron to create an ion with 17 protons, 17 neutrons, and 18 electrons, giving it a net negative (–1) charge. We now refer to it as a chloride ion.

In this example, sodium will donate its one electron to empty its shell, and chlorine will accept that electron to fill its shell. Both ions now have complete outermost shells. Because the number of electrons is no longer equal to the number of protons, each is now an ion and has a +1 (sodium cation) or –1 (chloride anion) charge. Note that these transactions can normally only take place simultaneously: in order for a sodium atom to lose an electron, it must be in the presence of a suitable recipient like a chlorine atom.

Ionic bonds form between ions with opposite charges. For instance, positively charged sodium ions and negatively charged chloride ions bond together to make crystals of sodium chloride, or table salt, creating a crystalline molecule with zero net charge.

Hydrogen Bonds

When polar covalent bonds containing hydrogen form, the hydrogen in that bond has a slightly positive charge because hydrogen’s electron is pulled more strongly toward the other element and away from the hydrogen. Because the hydrogen is slightly positive, it will be attracted to neighboring negative charges. When this happens, a weak interaction occurs between the hydrogen’s δ+ from one molecule and the molecule’s δ– charge on another molecule with the more electronegative atoms, usually oxygen. Scientists call this interaction a hydrogen bond.

This type of bond is common and occurs regularly between water molecules. Individual hydrogen bonds are weak and easily broken; however, they occur in very large numbers in water and in organic polymers, creating a major force in combination. Hydrogen bonds are also responsible for zipping together the DNA double helix.

Van Der Waals Interactions

Like hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions are weak attractions or interactions between molecules. Van der Waals attractions can occur between any two or more molecules and are dependent on slight fluctuations of the electron densities, which are not always symmetrical around an atom. For these attractions to happen, the molecules need to be very close to one another. These bonds—along with ionic, covalent, and hydrogen bonds—contribute to the proteins’ three-dimensional structure in our cells that is necessary for their proper function.

Functional Groups

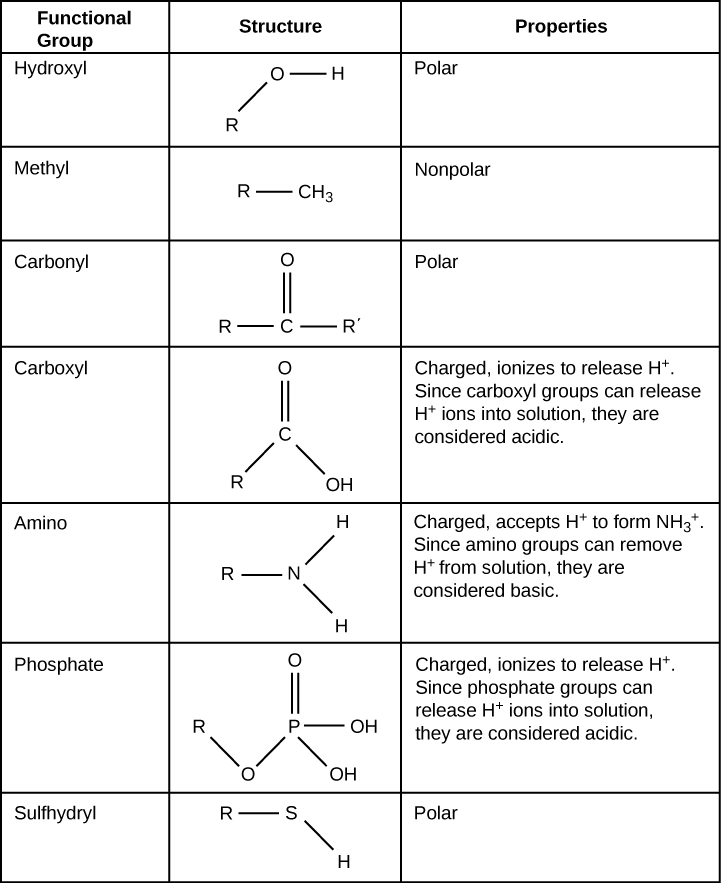

Functional groups are groups of atoms that occur within molecules and have their own specific properties. We find them attached to the “carbon backbone” of macromolecules. Chains and/or rings of carbon atoms with the occasional substitution of an element such as nitrogen or oxygen form this backbone.

The functional groups in a macromolecule are usually attached to the carbon backbone at one or several different places along its chain and/or ring structure. Each of the four types of macromolecules—proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids—has its own characteristic set of functional groups that contributes greatly to its differing chemical properties and its function in living organisms.

A functional group can participate in specific chemical reactions. The figure below shows some of the important functional groups in biological molecules. They include: hydroxyl, methyl, carbonyl, carboxyl, amino, phosphate, and sulfhydryl. These groups play an important role in forming molecules like DNA, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids.

We usually classify functional groups as hydrophobic or hydrophilic depending on their charge or polarity characteristics. An example of a hydrophobic group is the nonpolar methyl group. Among the hydrophilic functional groups is the carboxyl group that is found in amino acids, some amino acid side chains, and the fatty acids that form triglycerides and phospholipids. This carboxyl group ionizes to release hydrogen ions (H+) from the COOH group resulting in the negatively charged COO– group (still called a carboxyl group). This contributes to the hydrophilic nature of whatever molecule on which it is found. Other functional groups, such as the carbonyl group, have a partially negatively charged oxygen atom that may form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, again making the molecule more hydrophilic.

Hydrogen bonds between functional groups (within the same molecule or between different molecules) are important to the function of many macromolecules and help them to fold properly into and maintain the appropriate shape for functioning. Hydrogen bonds are also involved in other processes, such as pairing between complementary bases in double-stranded DNA molecules and the binding of an enzyme to its substrate.

Dissociation of Water

Hydrogen ions spontaneously generate in pure water by the dissociation of a small percentage of water molecules into equal numbers of hydrogen (H+) ions and hydroxide (OH–) ions. While the hydroxide ions are kept in solution by their hydrogen bonding with other water molecules, the hydrogen ions, consisting of naked protons, immediately attract to un-ionized water molecules, forming hydronium ions (H3O+). Still, by convention, scientists refer to hydrogen ions and their concentration as if they were free in this state in liquid water.

2 H2O ↔ H3O+ + OH–

Two water molecules dissociate into a hydronium ion and a hydroxide ion

H2O ↔ H+ + OH–

We simplify to this chemical reaction and consider H+ ions to calculate pH

The concentration of hydrogen ions dissociating from pure water is 1 × 10-7 moles[1] H+ ions per liter of water. We calculate the pH as the negative of the base 10 logarithm of this concentration. The log10 of 1 × 10-7 is -7.0, and the negative of this number (indicated by the “p” of “pH”) yields a pH of 7.0, which is also a neutral pH. The pH inside of human cells and blood are examples of two body areas where near-neutral pH is maintained.

pH = -log[H+]

This is the equation to calculate pH, where [H+] is the molar concentration of hydrogen ions

Acids and Bases

Non-neutral pH readings result from dissolving acids or bases in water. High concentrations of hydrogen ions yield a low pH number, and low levels of hydrogen ions result in a high pH. An acid is a substance that increases hydrogen ions’ (H+) concentration in a solution, usually by having one of its hydrogen atoms dissociate. A base provides either hydroxide ions (OH–) or other negatively charged ions that combine with hydrogen ions, reducing their concentration in the solution and thereby raising the pH. In cases where the base releases hydroxide ions, these ions bind to free hydrogen ions, generating new water molecules.

The stronger the acid, the more readily it donates H+. For example, hydrochloric acid (HCl) completely dissociates into hydrogen and chloride ions and is highly acidic; whereas the acids in tomato juice or vinegar do not completely dissociate and are weak acids. Conversely, strong bases are those substances that readily donate OH– or take up hydrogen ions. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and many household cleaners are highly alkaline and give up OH– rapidly when we place them in water, thereby raising the pH. An example of a weak basic solution is seawater, which has a pH near 8.0 This is close enough to a neutral pH that marine organisms have adapted in order to live and thrive in a saline environment.

The pH Scale

The pH scale is, as we previously mentioned, an inverse logarithm and ranges from 0 to 14. Anything below 7.0 (ranging from 0.0 to 6.9) is acidic, and anything above 7.0 (from 7.1 to 14.0) is alkaline or basic. Extremes in pH in either direction from 7.0 are usually inhospitable to life. The pH inside cells (6.8) and the pH in the blood (7.4) are both very close to neutral. However, the environment in the stomach is highly acidic, with a pH of 1 to 2. As a result, how do stomach cells survive in such an acidic environment? How do they homeostatically maintain the near neutral pH inside them? The answer is that they cannot do it and are constantly dying. The stomach constantly produces new cells to replace dead ones, which stomach acids digest. Scientists estimate that the human body completely replaces the stomach lining every seven to ten days.

Buffers

How can organisms whose bodies require a near-neutral pH ingest acidic and basic substances (a human drinking orange juice, for example) and survive? Buffers are the key. Buffers readily absorb excess H+ or OH–, keeping the body’s pH carefully maintained in the narrow range required for survival. Maintaining a constant blood pH is critical to a person’s well-being. The buffer maintaining the pH of human blood involves carbonic acid (H2CO3), bicarbonate ion (HCO3–), and carbon dioxide (CO2). When bicarbonate ions combine with free hydrogen ions and become carbonic acid, it removes hydrogen ions and moderates pH changes. Similarly, excess carbonic acid can convert to carbon dioxide gas which we exhale through the lungs. This prevents too many free hydrogen ions from building up in the blood and dangerously reducing the blood’s pH. Likewise, if too much OH– enters into the system, carbonic acid will combine with it to create bicarbonate, lowering the pH. Without this buffer system, the body’s pH would fluctuate enough to put survival in jeopardy.

H+ + HCO3– ↔ H2CO3 ↔ H2O + CO2

How the body buffers blood pH via the bicarbonate system

Other examples of buffers are antacids that some people use to combat excess stomach acid. Many of these over-the-counter medications work in the same way as blood buffers, usually with at least one ion capable of absorbing hydrogen and moderating pH, bringing relief to those who suffer “heartburn” after eating. Water’s unique properties that contribute to this capacity to balance pH—as well as water’s other characteristics—are essential to sustaining life on Earth.