Introduction to Animals

Animals are eukaryotic, multicellular, heterotrophic opisthokonts. Almost all animals (with the exception of Poriferans and Placozoans) have specialized tissue types. Almost all animals display aerobic respiration and the ability to move spontaneously (during at least part of the life cycle). Nearly all animals have Hox genes, which code for transcription factors that determine an animal’s body plan.

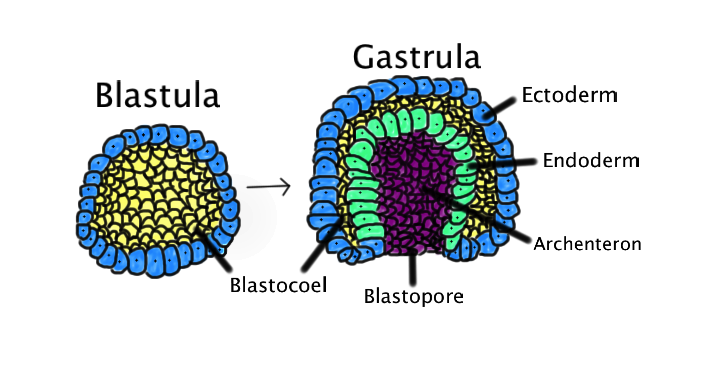

Animals, with few exceptions, have a common set of embryonic stages. The blastula and gastrula stages are unique to animals. During blastulation, the embryo is converted from a ball of cells to a hollow sphere of cells. This sets the stage for gastrulation, in which some cells migrate to the inside of the blastula. This cell migration results in the archenteron, which gives rise to the gut. The opening to the archenteron, the blastopore, will develop into the mouth or anus. Gastrulation also results in a two- or three-layer embryo. Diploblastic animals have two germ layers, endoderm and ectoderm, while triploblastic animals also have mesoderm, which is specified between the inner and outer germ layers.

Each germ layer gives rise to specific tissues. Many of these are unique to animals. For example, muscle tissue and nervous tissue are hallmarks of animals. These allow animals to rapidly and precisely respond to sensory information, which is key to their heterotrophic lifestyle.

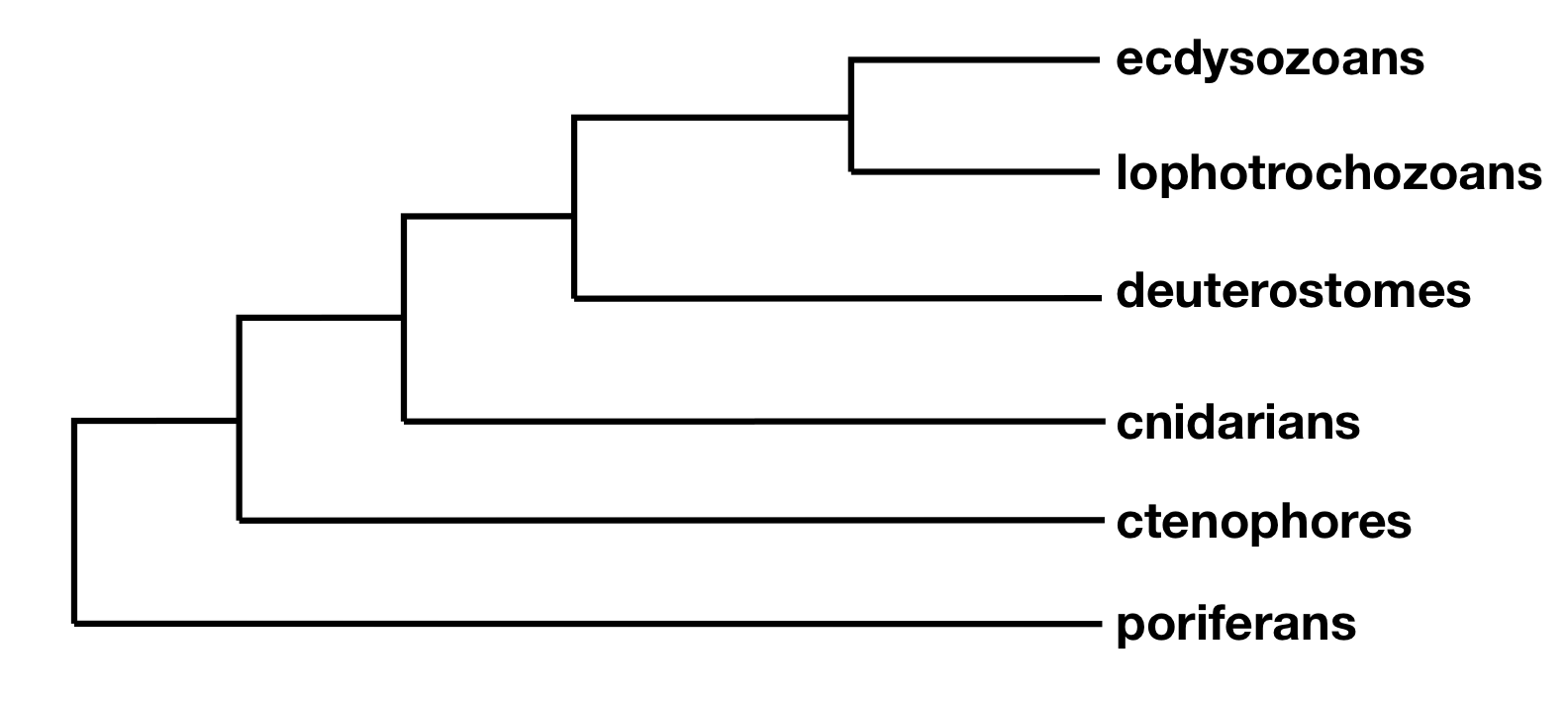

There are over 1.5 million described species of animals. About 1 million of these are insects. However, this is almost certainly a gross undersampling of total animal species, which has been estimated to be from 3 to 30 million or more. We will consider three major clades of animals, each of which contains multiple phyla, plus two phyla of “basal animals”.

The phylogenetic tree shown is the leading hypothesis for the evolutionary history of major animal groups. Basal animal phyla include poriferans, cnidarians, ctenophores, and placozoans (not shown on tree). Note that this is not a monophyletic group, just an informal designation. All other animals are bilaterians, meaning that they display bilateral symmetry. Bilaterians include the deuterostomes and protostomes. These are distinguished by several features of embryonic development, and are named for whether the blastopore becomes the mouth or the anus. Deuterostomes (anus first) include chordates, hemichordates, and echinoderms. Protostomes (mouth first) are further divided into two groups, the ecdysozoans and the lophotrochozoans. The ecdysozoans are animals that grow by ecdysis, a specific kind of molting, and include the arthropods, nematodes, onycophorans, tardigrades, and a handful of other phyla. The lophotrochozoans are the largest group by number of phyla, and include the annelids, platyhelminths, molluscs, and a number of other phyla.