Why Study Literature?

Stacey Van Dahm

If you are here, reading this article, you might already know how important reading literature is. But if someone asks you, “Why study literature?” how would you answer? It’s an age-old question we once again face at a time when choosing what to study in college is tied to rather limited assumptions about what “success,” or a “good income,” or the very purpose of a college education actually is. In fact, the discussion about why we study literature is directly related to the general education or liberal arts curriculum at any institution of higher learning. These programs adhere to the notion (supported by research) that studying literature, philosophy, and art (i.e., the Humanities) makes us better people — more responsible, ethical, and civically engaged.

This is true, but that’s not exactly the conversation I want to have here. Instead, I want to start with a 200,000-year-old handprint.

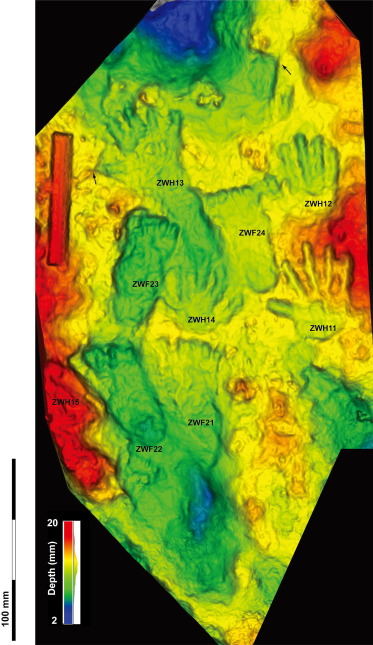

In 2021, Archaeologists discovered the earliest known cave art in the Quesang village in the Tibetan Plateau. The hand- and footprints discovered, it turns out, were made by 7- and 12-year-old hominin species children[1], somewhere between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago during the Middle Paleolithic period (Zhang et al). The journal Science Bulletin, originally publishing the findings, includes these two images of the prints:

CCBY-NC-ND 4.0 / image cropped pursuant to fair use.

I include the images because they help us to imagine the children, who “squished their hands and feet into sticky mud” (Lanese) to leave the prints deliberately, which opens up a fascinating question about whether or not this is “art.” Matthew Bennet, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in Poole, England, likens the composition to the scribbling of a toddler that a parent might hang on the fridge as “art.” It is intentional and playful. The implication is that, as a deliberate composition, it is artistic.

One of the ways we might understand these handprints is to tell their story. It seems the children were together, playing in the mud. I imagine them enjoying the feeling of wet mud squishing between their toes and fingers, the smell of earth and leisure. Perhaps they were siblings or cousins or similarly related young people attached to the same band of Denisovans or Homo erectus. Maybe one of them, the youngest — after having observed the other for some time — stuck their foot in the mud and lifted it straight up, out of some interest, a curiosity. The other sees this and does the same, and before long, they are taking it in turns, nudging each other out of the way, to slowly fill up the space with various hand- and footprints. Perhaps, liking the results, they left those prints there. Or maybe they were wrenched away from this “play” suddenly, out of some necessity, never to return. Either way, they hardly could have imagined that 200,000 years later scientists would find the marks preserved by the slow-moving forces of geological fate, to be discovered and studied during the so-called Anthropocene period.

Some cave drawings more definitively categorized as “figurative art” date back about 40,000 years and are found in Indonesia. The depictions of hands made with a stencil technique, as if outlined “against a background of red paint,” or the figures of animals once common in the area, shifted our assumptions about the origins of art. Scientists understand these figures to be an indication of the “moment when the human mind, with its unique capacity for imagination and symbolism, switched on” (Marchant). To put this in other terms, we have long understood art to be a sign of something unique about human beings and their sensibility.

These examples light up our own curiosity. What were these human ancestors trying to capture as they drew figures of themselves and animals? What kinds of rituals or rites of passage included marking walls with handprints? How did early humans imagine themselves and their surroundings? How did they imagine themselves in relation to others? Why did they feel compelled to express their experience in visual images and stories? Is our amazing ability to imagine and represent experience beyond the self a unique sign of humanity?

What we see in early artistic endeavor is, really, ourselves. And our thirst to understand the drawings and stories and relics of the past has very much to do with a quest to understand human experience and our own place in it. In fact, the creation of stories, narratives, is very much about making meaning of the world, as explained in Clint Johnson’s, “What Is Story?”

Indeed, the story that I’ve told you so far is really a way to make sense of something. In fact, you will notice that the telling of this story included some make-believe — an anecdote of young people playing in mud — but also lots of other modes of inquiry and knowledge building: anthropology, geology, biology, and paleontology, for example.

My argument is that literary study is important because it is one more form of studying the artifacts of people over time, the kinds of artifacts that help us understand ourselves in historical context. Literary study is the study of the stories people have told about human experience throughout time. Cave drawings, like stories, suggest the centrality of aesthetic sensibility to human experience. They spark our curiosity, and they show us we have a deep and connected human history that demonstrates a compulsion to create and leave a mark. Literary art is like that handprint in the mud; it is the imprint of a mind, a sensibility captured in artistic creation composed of words.

Literary study awakens our aesthetic sensibility.

It may be surprising that a handprint in the mud can inspire aesthetic wonder. But many of us have been moved by literary images that unfold before us as we read. These images are powerful because they happen in our minds and hearts. It is one of the ways that the experiences of literary characters become deeply embedded in our own emotional lives. Aesthetic experiences make us feel.

Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez’s novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is filled with passages that evoke a sense of beauty both through imagistic descriptions and the kinds of human experiences they are attached to. The novel tells the story of a family over multiple generations in a small town in Columbia called Macondo. The death of José Arcadio Buendía, the patriarch of the family and the founder of the community, is represented in a way that evokes the gravity of the loss:

Entonces entraron al cuarto de José Arcadio Buendía, lo sacudieron con todas sus fuerzas, le gritaron al oído, le pusieron un espejo frente a las fosas nasales, pero no pudieron despertarlo. Poco después, cuando el carpintero le tomaba las medidas para el ataúd, vieron a través de la ventana que estaba cayendo una llovizna de minúsculas flores amarillas. Cayeron toda la noche sobre el pueblo en una tormenta silenciosa, y cubrieron los techos y atascaron las puertas, y sofocaron a los animales que durmieron a la intemperie. Tantas flores cayeron del cielo, que las calles amanecieron tapizadas de una colcha compacta, y tuvieron que despejarlas con palas y rastrillos para que pudiera pasar el entierro. (Cien Años 166)

Then they went into José Arcadio Buendía’s room, shook him as hard as they could, shouted in his ear, put a mirror in front of his nostrils, but they could not awaken him. A short time later, when the carpenter was taking measurements for the coffin, through the window they saw a light rain of tiny yellow flowers falling. They fell on the town all through the night in a silent storm, and they covered the roofs and blocked the doors and smothered the animals who slept outdoors. So many flowers fell from the sky that in the morning the streets were carpeted with a compact cushion and they had to clear them away with shovels and rakes so that the funeral procession could pass by. (One Hundred Years 140)

The passage, beautiful in both Spanish and English, conveys the enormity of the loss in a surprising, magical scene that combines wonder and sadness. Falling yellow flowers make the loss visible, shared, throughout the whole community. It seems as if a higher power is responding to death with a “tormenta silenciosa,” a “silent storm” that blankets the town. The way that Gabriel García Márquez juxtaposes death with beauty in this scene touches our own sense of loss, uniting the literary image of grief with our own understanding of suffering. Falling yellow flowers remind us that suffering loss is always paired first with having loved.

These kinds of literary images live within us after we read a book, and they color our vision of the world and our ways of interacting with it.

Literary study activates our curiosity.

Literature also drives us to get answers to our questions, to ask and to explore. This is one of the things people mean when they say that literature “opens our minds.” When we are curious, we engage with the world by asking questions and listening carefully and thoughtfully to the answers we encounter. This way of facing life makes it much harder to judge others and shut out new ideas, and it makes it much easier to understand things that are unfamiliar.

A short story published in 2016 by Helen Oyeyemi, “Is Your Blood as Red as This?” is filled with curiosities. Some of the main characters in the story are … puppets — puppets who manipulate their handlers and each other with the verve of jealous children and the intensity of young lovers. The story defies simple explanation, but we see from the start that desire will be a driving force in the story when the main character, Rhada Chaudhry, a schoolgirl, meets another central character, Myrna Semyonova, and becomes determined to win her heart. She sets out to do so by telling stories. “I discovered that I could talk to you in natural, complete sentences. It was simple: If I talked to you, perhaps you would kiss me. And I had to have a kiss from you: To have seen your lips and not ever kissed them would have been the ruin of me …” (101). This desire initiates a metaphor of storytelling as an alternating current that animates both the teller and the listener. And it pricks our curiosity. Will she get the girl?

As it turns out, this isn’t the right question. This story makes us curious by defying our expectations. It seems like a romance, but Oyeyemi’s love tangle becomes secondary when the story shifts to center puppetry, a surprising form of storytelling. Puppets, directed and manipulated by a puppeteer, enact stories, but in Oyeyemi’s world, when one small puppet asks, “Is Your Blood as Red as This?” the puppet master disappears, and with them, so do readers’ assumptions about how stories work. At first, Rhada joins Myrna’s puppet school saying, “I don’t feel one hundred percent sure that I’m not a puppet myself” (108). But soon, Rhada’s puppet, Gepetta, takes over the narration of the story, commenting on Rhada’s crushes, telling the history of enigmatic puppet, Rowan, with whom she listens to music while riding night buses since, she says, “neither of us needs sleep” (129). As the puppets manipulate their handlers and overtake our imaginations, we readers find ourselves delightfully lost. We are no longer in a romance or a puppet show. Eventually, someone, perhaps a jealous and long-suffering puppet, orchestrates a crime that exposes all the characters’ hidden suffering, fear, and desire. The story suggests that we are just as likely to be manipulated in the stories of our lives, pulled by the strings we pretend are not there.

This is a story that raises many questions about the human condition. How do my assumptions about stories blind me to how I’m reading? What expectations and assumptions do I hold that cause me to misinterpret others? Is it possible for me to truly see others or for them to see me? Why are we so unaware of the suffering and pain of those around us? To what extent do my own desires and hidden fears hold me back?

Literature piques our interest in both the magic of a fantastic tale and the complexity of human experience. In this case, literature makes us curious about our own choices and our own behavior in the face of human fragility, including our own.

Literary study also deepens our historical and critical perspective.

You likely remember learning about another historical period through reading. Literary texts draw readers into a time and place different from our own. Immersed in a literary world, we discover the values, beliefs, and systems that shape human behavior. Reading literature opens us to a critical examination of our shared humanity with fictional others.

In Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas’ novel Hallucinations, the author explores critical issues of religious and political oppression through a fantastical story about the struggle for Mexican independence from Spain. In it, he uses hyperbolic and outrageous depictions of the Spanish Inquisition as a metaphor for the brutality of colonial systems of power. Near the opening of the novel, Arenas includes descriptions of the Inquisitorial pyres that “burned night and day at the end of every street, so that heat and soot were perpetual in the city and on summer days made it unbearable” (14). His exaggerated descriptions include mobs “crowded about the flames” (14), lines of people waiting to be burned in the fires, and protesters choosing to die “an unchristian death, without the final benefaction conferred by confession” just to flout “the orders of the Holy Inquisition” (15). In order to highlight the absurdity of abusive power and passive obedience, Arenas depicts the hypocrisy of church leaders condemning people to the punishment of the church for the sake of political power and the abuse of the most humble members of society, especially the Native Americans, whom the church claims to be there to save.

There is no way to read these passages of historical fiction without critically examining the truth of these historical events. Was the Spanish Inquisition truly this brutal? How many people were condemned to death? To what extent were these choices, played out in colonial cities, actually about solidifying power for individuals, for governments? How did spiritual manipulation affect the outcome of the conquest in Latin America? How did this historical moment shape the world as we know it today? For Arenas, the biggest question seems to be about how the desires and fears of just one person can influence choices and actions that change the lives of multitudes, even the direction of history.

When we encounter literary events that touch our own sense of shared humanity, we ask critical questions about the world around us. In this way, literature helps us to build an historical understanding of everyday life. Literature helps us critically examine such choices and how we, like the characters we love, might also be susceptible to the forces of desire that determine the course of history: the contradictions of fear and love, desire and humility, or pride and compassion.

Why study literature?

For many of us, reading brings great pleasure. But when it comes to college, studying literature makes us better people. That claim might seem overstated, but it is not. When we gain awareness of our aesthetic sensibility, we live in the knowledge that part of what makes us human, part of what we share with all people, is a need for beauty and an urge to create it. When our curiosity is sparked by a literary image, a moving theme, or the complex contradictions of human behavior, we become better at investigating the world around us. And when literature immerses us in another’s experience and another world, we become more able to critically examine our own lives and our own behavior. Studying literature makes us more human, more humane.

Works Cited

Arenas, Reinaldo. Hallucinations: Or, the Ill-fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando. Translated by Andrew Hurley. Penguin. 2002.

García Márquez, Gabriel. Cien Años de Soledad. Madrid: Alfaguara, 2007.

García Márquez, Gabriel. One Hundred Years of Solitude. Translated by Gregory Rabassa. Harper Perennial, 2006.

Lanese, Nicoletta. “Kids’ Fossilized Handprints May Be Some of the World’s Oldest Art.” Scientific American, 21 Sept. 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/kids-fossilized-handprints-may-be-some-of-the-worlds-oldest-art/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2022.

Marchant, Jo. “A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World.” Smithsonian Magazine, Jan. 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journey-oldest-cave-paintings-world-180957685/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2022.

Oyeyemi, Helen. “Is Your Blood as Red as This?” What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours. Riverhead Books, 2016. 95-151.

Zhang, David D., et al. “Earliest Parietal Art: Hominin Hand and Foot Traces from the Middle Pleistocene of Tibet.” Science Bulletin, vol. 66, no. 24, Dec. 2021, pp. 2506–15. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.libprox1.slcc.edu/10.1016/j.scib.2021.09.001.

- These were a subspecies of archaic humans thought to be either Denisovans or Homo erectus. ↵