10 Understanding Postcolonial Theory

Maggie Walton

“Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter.”

― J. Nozipo Maraire

In 1978 Edward Said, a Palestinian-American scholar and literary critic, published a groundbreaking book titled Orientalism, which was a critique of Western representations of Arabic culture and Islamic traditions. In his work, Said condemned the use of stereotypes that glorified Western culture while reducing its Eastern counterparts to barbaric or exotic caricatures. Orientalism was a transformational work that earned global acclaim for its stark observations of how people of the global majority often are “othered” in many works of Western literature: treated either as untrustworthy aggressors or else as subservient, child-like creatures, incapable of sustaining their own resources. Though Said was not the first academic to view Western literature through a racial lens (Said named writers Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire among his many influences), the popularity of this text opened the door for other critics of colonialism whose voices longed to be heard.

Like other forms of literary theory that seek to analyze works of art and literature through a specific social lens, postcolonial theory is a “body of thought primarily concerned with accounting for the political, aesthetic, economic, historical, and social impact of European colonial rule around the world in the 18th through the 20th century” (Elam). Postcolonial theorists often take a multifaceted approach to textual analysis, seeking to simultaneously examine the ways in which imperialism has affected the lives of indigenous cultures and also uplift these respective cultures by challenging myths and misconceptions in global literature. As Said once proclaimed, “We can not fight for our rights and our history as well as [the] future until we are armed with weapons of criticism and dedicated consciousness” (“Edward Said on Culture, History, Criticism, Imperialism, and More”).

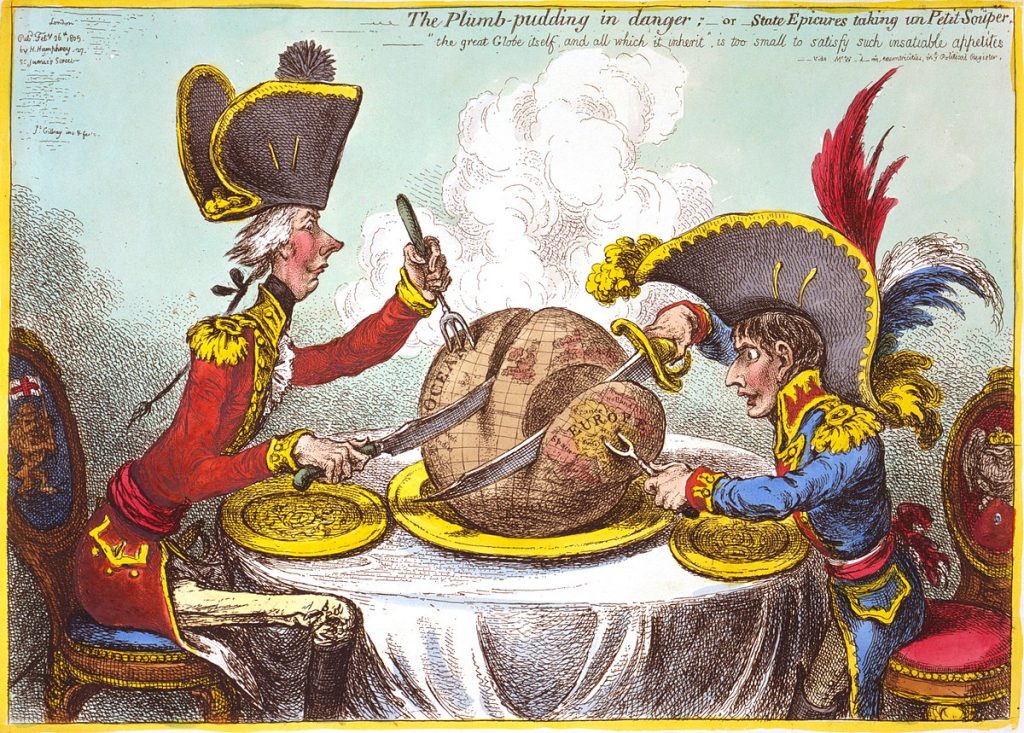

“The Plum-Pudding in Danger” by James Gillray. Public Domain. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Unmasking the Brutality of Imperialism

In her landmark TED talk “The Danger of a Single Story,” Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explained the issue with people of the global majority (Indigenous African, Asian, and Latin American people who make up 85% of the world’s population) being largely absent or unfairly represented in early literature. In her speech, Adichie referenced the Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti, who said, “if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story, and to start with ‘secondly.’” In other words, explained Adichie, “Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story.” By that rationale, it would be inappropriate to begin a discussion of postcolonial literature by analyzing the response of the oppressed and not the actions of the oppressor.

Between the 15th and the 20th centuries, European empires had a foothold in many countries around the world, inspiring the saying, “The sun never sets on the British empire.” Between the transatlantic slave trade, widespread starvation caused by unfair trading policies that devastated native manufacturers, and exploitative practices concerning different countries’ natural resources, the death toll from early colonial practices resulted in hundreds of millions of deaths. Among the atrocities committed by early European regimes were the Boer Concentration Camps in South Africa, where native Africans, in addition to Boer farmers, were rounded up and placed in concentration camps where many died as a result of disease and starvation. There were also famines in India, where “Between 12 and 29 million Indians died of starvation while it was under the control of the British Empire, as millions of tons of wheat were exported to Britain as famine raged in India” (Osborne). Elsewhere there was the French occupation of Algeria, where “within the first three decades of the conquest, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Algerians, out of a total of 3 million, were killed by the French due to war, massacres, disease, and famine” (Gençoğlu). These events and many others destroyed generations of families and effectively destabilized the economic, educational, and societal systems in their respective countries.

Those who survived the violent expansion of these empires lived on to bear the burden of forced assimilation, or having to adopt the language, culture, and traditions of their subjugator in lieu of their own ancestral ties. This was the price of survival. In a lecture titled “Decolonize the Mind: Secure the Base,” delivered by Kenyan author Professor Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, he discussed the devastating effect of colonization on native languages and culture. As Thiong’o explained, “In colonial conquest, language was meant to complete what the sword had started; do to the mind what the sword had done to the body” (Edoro). The disappearance of hundreds of indigenous languages, as shown in a recent report, lends credence to Thiongo’s words:

“Colonialism has driven many Indigenous languages to extinction. In Australia, of the existing 200 to 300 aboriginal languages, only 60 are considered unthreatened. The Indigenous Language Institute estimates that over 300 Indigenous languages were spoken in the U.S. at the time of initial European settlement. As of 2022, only 175 are still spoken. Currently, a significant number of languages have few remaining speakers and are in danger of extinction” (“Effects of Colonization and Climate Change on Indigenous Languages”)

Younger generations are abandoning traditions to seek more formal education and pursuing Western notions of success. With the physical and psychological scars of imperialism still fresh in the minds of many indigenous peoples, they turn to art and academics as a platform for speaking out against the wrongs of the past, giving birth to what we now call postcolonial theory.

Themes of Postcolonial Theory and Literature

As mentioned before, postcolonial theory and criticism offer a lens through which to analyze the degree to which past and contemporary literature upholds or subverts colonial ideals that indigenous people were morally and intellectually inferior and, therefore, not entitled to human treatment. For instance, Said famously deconstructed Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park in his book Culture and Imperialism, pointing out how casually it normalized racist institutions such as slavery. There is a reference to a character tending to their sugar plantation the way one would speak of going to an office job. This serves as an example of how literature can uphold colonial ideals by mentioning nothing of the brutality of the practice. Meanwhile more contemporary authors like Audre Lorde used their art to dismantle colonial attitudes, including those internalized by racial and ethnic minorities. Lorde’s famous essay collection, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” sought to empower minority groups and help them understand the nature of their oppression. Postcolonial literature also allows artists from previously colonized territories to rewrite history. A major theme in postcolonial literature is resistance, as writers often attempt to reclaim narratives commonly seen in history books and novels that attempt to justify the violence and cruelty used against their people. Nigerian author Chinua Achebe wrote in his novel Anthills of the Savannah, “Those who mismanage our affairs would silence our criticism by pretending they have facts not available to the rest of us. Our best weapon against them is not to marshal facts, of which they are truly managers, but passion. Passion is our hope and strength” (35). Achebe knew that storytelling is a powerful tool that can amplify people’s voices and shed light on hidden struggles. Things Fall Apart, Achebe’s most successful novel and a literary classic, was translated into at least 45 different languages, providing an opportunity for cultures across the globe to understand the impact of colonialism through the plight of its main characters and to see similarities between the many different stories of oppression worldwide.

Another theme in postcolonial literature is identity. Writers in this genre commonly address the dilemma of having to either embrace or reject their own cultural values in favor of Western lifestyles. Some people in formerly-colonized countries choose to embrace Western identities due to internalized racism or self-hatred spurred by racial stereotypes perpetuated by colonizers. Others embrace these ideals in the interest of upward mobility and being able to navigate through the modern world. In the novel The Bluest Eye, author Toni Morrison offers this heartbreaking description of how internalized racism has affected the characters in the story: “They seemed to have taken all of their smoothly cultivated ignorance, their exquisitely learned self-hatred, their elaborately designed hopelessness and sucked it all up into a fiery cone of scorn that had burned for ages in the hollows of their minds― cooled ―and spilled over lips of outrage, consuming whatever was in its path” (65). What passage could better describe the vitriol that people spew against members of their own race that often mirrors the very words of their oppressors?

Despite the merits of postcolonial studies, it has not escaped controversy. There are many arguments within the literary community about the authenticity behind claims concerning the cruelty of colonization, suggesting many accounts are exaggerated, while others acknowledge the atrocities, only to bargain that this was a necessary evil that ultimately “civilized” these countries and helped them abandon archaic and harmful practices. Some critics take issue with the “post” part of the term, arguing that colonialism is still alive and well today. Professor Paul Brians of Washington State University observed that critics argue the term is misleading since “most of the nations involved are still culturally and economically subordinated to the rich industrial states through various forms of neo-colonialism even though they are technically independent” (Brians). There is also a question of whether it is even possible for writers from colonized countries to “reclaim” their heritage while using the language and means of production of their oppressors.

Controversy notwithstanding, postcolonial studies is a field that continues to grow. While many nations attempt to rebalance themselves in the wake of the trauma of exploitation, others still live in the shadows of other nations. When independence is achieved, I suspect that it will birth even more stories of peril and survival.

| Notable Authors of Postcolonial Literature | Best-Known Works |

| Chinua Achebe | Things Fall Apart |

| Frantz Fanon | The Wretched of the Earth; Black Skin, White Masks |

| Jamaica Kincaid | A Small Place |

| Salman Rushdie | Midnight’s Children |

| Edward Said | Orientalism; Culture and Imperialism |

| Homi K. Bhabha | Nation and Narration |

Works Cited

Adichi, Ngozi Chimamanda. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TED, 6 Oct. 2009, https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

Brians, Paul. “‘Postcolonial Literature’: Problems with the Term.” Washington State University, 5 Jan. 2006, https://brians.wsu.edu/2016/10/19/postcolonial-literature-problems-with-the-term/.

Elam, J Daniel. “Postcolonial Theory.” Oxford Bibliographies, 15 Jan. 2019, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0069.xml

Edoro, Ainehi. “14 Best Quotes from Ngugi’s Johannesburg Lecture on Reviving African Languages.” BrittlePaper, 6 Mar. 2017, https://brittlepaper.com/2017/03/14-quotes-ngugis-johannesburg-lecture-reviving-african-languages/

Gençoğlu, Halim. “French Colonial Legacy in Algeria.” United World, 12 Oct. 2021, https://uwidata.com/21460-french-colonial-legacy-in-algeria/

Gestalt, Andrew. “10 Political Cartoons with Powerful Messages.” Listverse, 9 Sept. 2023, https://listverse.com/2023/09/09/10-political-cartoons-with-powerful-messages/.

Madera, John. “Edward Said on Culture, History, Criticism, Imperialism, and More.” Big Other, 1 Nov. 2022, https://bigother.com/2022/11/01/edward-said-on-culture-history-criticism-imperialism-and-more/

Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye. Vintage Books, 1970.

Osborne, Samuel. “5 of the worst atrocities carried out by the British Empire.” The Independent, 19 Jan. 2016, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/worst-atrocities-british-empire-amritsar-boer-war-concentration-camp-mau-mau-a6821756.html

Smith College. “Effects of Colonization and Climate Change on Indigenous Languages” Climate in Arts and History, Smith College, n.d., accessed 12 Feb. 2024, https://www.science.smith.edu/climatelit/effects-of-colonization-and-climate-change-on-indigenous-languages/