9 Part 3: Korea (East Asian Literature and Literary Criticism)

Daniel Baird

For Part 3, we now turn to Korean literature.

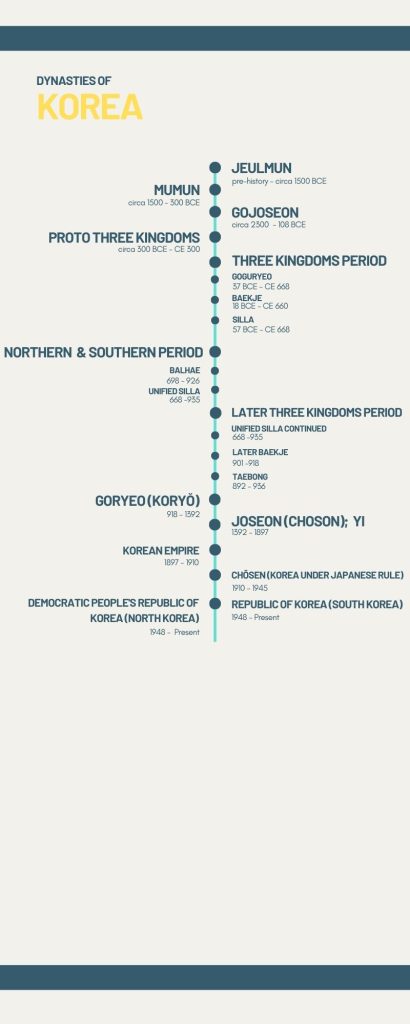

Literature in Korea began when Chinese writing arrived along with Buddhism in the Proto-Three Kingdoms Period (c 300 BCE – 300 CE) and was adapted for the Korean language. In the 1400s King Sejong[1] the Great developed a phonetic system, Hangul, to use to aid in reading Chinese writing, and in the case of some writing such as fiction, replace the Chinese writing system altogether. Korean literati (scholar officials) were familiar with Chinese writers and literary movements, and they often wrote in Chinese, especially for official documents, but they also wrote in Korean, first by using Chinese characters to represent the Korean language and later in Hangul.

Major Influences on Literature

Ideas about literature throughout Korean history find expression in many ways: from the early writing influenced by Buddhism to Neo-Confucian morals and the stress of imitating ancient Chinese writers to the reaction against Neo-Confucianism by emphasizing individual feeling and experience. Here we can only offer a brief look at Korean literature but we hope that you will be interested in exploring more.

In Korea, Daoism became integrated into shamanism. We know from records that during the Three Kingdoms period a Daoist teacher brought Daoism including scriptures to Korea; however, by the mid Goryeo Dynasty Buddhism dominated and Daoism waned. Although some continued to practice Daoism and Daoist literature was at times quite popular, Daoism never saw the same level of prosperity in Korea as it did in China.

Buddhism spread during the Three Kingdoms period via China. Starting first with the aristocracy Buddhism worked its way down to the common people who integrated it with the native Shamanism. The monk Jinul (1158–1210) had a great influence on spreading Seon (Zen) Buddhism during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392).

It was during the Three Kingdoms Period that Confucianism entered Korea, first into Goguryeo then the other two kingdoms. In the Goryeo Dynasty, Buddhism was the state religion. Yet by the late Goryeo Dynasty Neo-Confucianism became influential. Korea also adopted the civil examination during this dynasty. Eventually the Neo-Confucianists overthrew the Buddhist Goryeo Dynasty and established Neo-Confucianism as the state ideology in the new Joseon Dynasty.

(For more on Buddhism, Daoism, and Neo-Confucianism, see Part 1: China.)

Thus, for most of Korea’s history, Confucianism was by far the dominant ideology. Literature either fell in line with Confucian values or responded to them. The dominance of Confucianism was maintained by the civil examinations—all those desiring to enter government service had to take them. The virtues of propriety, ethical rule, and Confucian social order were cultivated. Scholars and government officials were expected to be familiar with the Confucian literary canon and Chinese poetry.

Literary Themes and Ideas

Vernacular fiction (written in Hangul rather than Chinese) blossomed in the 17th century. These works were popular among commoners, court ladies, and many literati. Early stories tended to have a hero who displayed Confucian virtues such as filial piety. These stories usually featured the supernatural as well.

Some themes that were common to Korean literature include:

- Confucian values such as filial piety, or the idea that inner virtue can be cultivated

- A didactic bent, meaning that these stories emphasize moral and social conduct, whether via Confucian or Buddhist values

- Folktales that include the supernatural or tales of wonder

For a list of some important authors and literary works, see Appendix 1. For an introduction to literary criticism. see Appendix 2.

Some Important Authors and Works of Korean Literature

Fiction

The beginning of classical fiction is marked by New Stories from Golden Turtle Mountain written by Kim Si-seup (1435-1493). This work contains five stories in the tradition of Chinese wonder tales and includes tales about love affairs between humans and ghosts as well as dream journeys to underworld or a dragon palace in the sea or rivers. Although influenced by the Chinese tradition, these stories are set in historically significate places of Korea and depict Korean culture.

The most famous Korean novel is the Tale of Hong Gil-Dong by Heo Gyun (d. 1618). This novel is a fictionalized account of a real thief and rebel from the 1400s. The story is told in a three-part structure, recounting (1) Hong’s youth, (2) his time as head of a robber gang, and (3) his time as king of an island—this last section is written as a utopia. Heo uses the novel as social criticism, such as critiquing the policy that sons born to concubines were not eligible for either military or civil service. The story remains extremely popular in Korea to the present day. (Read more about the author in the “Literary Criticism” section below.)

Another very popular work is The Cloud Dream of the Nine by Kim Man-jung (1637-1692). Kim was an important Neo-Confucian scholar, and it is thought that he wrote his novel during one of his exiles from the imperial court. The novel is set in the Chinese Tang Dynasty and follows the story of a Buddhist monk who, because of lustful desires for eight fairies, is punished to be reborn as what can only be described as the ideal Confucian man. He rises from poverty through the ranks of the Tang government. He marries all eight of the fairies, who all have been reincarnated as women. In the end he overcomes his desires and awakens to realize it had all been a dream. In addition to the important Buddhist concepts and themes, this novel contains Confucian social criticism, especially of the king who had exiled the author.

Other Literature

One of the most important Korean anthologies of literature is the Selections of Refined Literature of Korea compiled in 1478. It covers the late Three Kingdoms Period (300-668) to early Joseon (1392-1897) and contains some 5000 works by almost 600 literati.

Only two chapters are extant of the Lives of Eminent Korean Monks (1215), which was written by the Buddhist monk Gakhun (dates unknown). These two chapters cover some 500 years and the lives of over 20 monks. In addition, it details the establishment of Buddhism in Korea.

Another important Buddhist work is the anthology Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (c .1285), which was written by the Zen Buddhist monk, Iryon. Memorabilia collected myths, legends, and stories mainly from the Three Kingdoms Period, but also from other periods as well. It had a significant influence on later popular fiction.

Literary Criticism

Buddhism was the official state religion of the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) and contributed greatly to Goryeo literature. It was during this time that the idea of teaching theology and moral behavior through storytelling and writing was common.

By the late Goryeo period the Chinese civil service examination was adopted and this created a groundswell of candidates trained in classical Chinese writing, especially poetry. Similarly important in the late Goryeo was the influence of the Chinese Ancient Prose Movement and the idea of ancient Chinese texts serving as models for good writing. Along with this influence, literati began to discuss composition, rhetoric, and the value of poetry. Two particularly important ideas emerge from the discourse of this period: 1) a concern with language and writing in Chinese and 2) a debate between form and creativity.

Central to this debate was the “Eminent Assembly in the Bamboo Grove,” a group of literati who were important to the creation of literary criticism in Korea as they debated literary theory and artistic creation. One important member of this group was Yi Kyubo (1168–1241). Yi believed poetry should respond to the real world and to the demands of the time rather than simply imitating the ancients. He emphasized creativity without entirely dismissing form.

Later the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897) established Neo-Confucianism as the state ideology. The overriding meaning was that literature should guide one both morally and socially. This eventually led to an argument over individual creativity versus established tradition. Scholars began to study and debate the importance of the sources of texts, the author’s relation to a text, and the importance of language.

Two literati can be said to represent the values in literature of this time. The first is Yi Saek (1328-1396), who studied in China and was very important in bringing Neo-Confucianism to Korea. Unlike some others, however, he didn’t reject Buddhism but instead sought for the co-existence of Confucianism, Buddhism (and Daoism).

The second was Jeong Do-jeon (1342-1398), a contemporary of Yi Saek. Jeong is known foremost because he wrote a code of laws that became Joseon’s constitution. He also was very Neo-Confucian in his ideas towards literature: literature is for perfecting virtue. In other words, this is the idea that one is born with an inner morality that must be cultivated, and literature is one of the important means through which one can cultivate virtue. Therefore, proper literature brings about proper order in society.

The Japanese invasion of 1592–97 demarcates the earlier Joseon and later Joseon. In the late Joseon, while some literati re-emphasized Confucian values of family, state, and the great kings of the past, others championed writing as an expression of emotion or intent of the heart and the idea that it can evoke an echo in the reader.

Heo Gyun (1569-1618) is another of the literati who can be considered as representing the new ideas that emerged in the later Joseon. Heo sought to promote a society that was not constrained by the rigid ideas of Neo-Confucianism. Heo felt that poetry was the truest expression of feelings, and he criticized imitating classical Chinese and promoted vernacular Korean. Heo further argued that each period in history has unique literary trends and writers should write from their own experience rather than copying the past. In this latter idea Heo can be thought of as building on Yi Kyubo’s ideas. He is most famous for potentially being the author of the novel Hong Gildong. Heo was exiled and eventually executed for his ideas.

A generation later, Kim Man-jung (1635-1720) extended discussions of literary criticism to vernacular Hangul writings and started a shift in literary criticism away from classical Chinese to native Korean literature. He is also author of The Cloud Dream of the Nine.

Around the time of Kim’s writing another influential literary school appeared, the Practical Learning School. They attacked Neo-Confucianism and promoted a practical approach to governing including social reform. Many of those associated with this school also identified as students of Western thought and technology.

Seongho Yi Ik (1681-1763) was one important figure of this new movement. One of Yi Ik’s writings, Introductory Essays on Songs from Everyday Life, discussed the views of the Practical Learning School. According to Yi, everyday experience was to be promoted rather than imitating models of the past, and therefore literature must reflect the many ways of life both now and in the past. He felt that the focus of literature should be on understanding society and the best way to understand society was to understand the love between men and women.

In the late 1700s there also emerged the Wihangin literary movement. The poets of this movement sought to write with greater realism and individuality by rejecting ancient Chinese models. They sought to promote instead the sincerity and natural expression of the common people and they referred to their poetry as “poems of the people.”

Conclusion

If you have read all three parts of this series, then you have been given a brief taste of the literature of East Asia. It is my hope that this series both helps you understand a little better and encourages you to read more. I also hope that when you encounter related media like movies – whether they are from East Asia or produced here in the US – you will be able to recognize and enjoy them better because of what you have learned.

[1] Please note that there are two commonly used systems of representing Korean in English. This article uses the official romanization of South Korea: Revised Romanization of Korean, except where titles or names are commonly rendered in English using McCune-Reischauer romanization.

Further Reading and Resources

Chong, Byong-Wuk , Kwon, Du-Hwan and Lee, Peter H. “Korean literature”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 4 Jan. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/art/Korean-literature.

Great Big Story. “Pansori: South Korea’s Authentic Musical Storytelling.” YouTube, uploaded by Great Big Story, 21 Aug. 2017, https://youtu.be/8Kt7YdXsWzg

Kim, Hunggyu. Understanding Korean Literature. Robert J. Fouser, trans. M.E. Sharpe, 1997.

Korea’s Premier Collection of Classical Literature. Korean Classics Library: Historical Materials. Trans. Xin Wei and James B. Lewis. University of Hawaii Press, 2019

Lee, Peter, ed. An Anthology of Traditional Korean Literature. U of Hawai’i Press, 2017.

—. A History of Korean Literature. Cambridge UP, 2003.

Rutt, Richard. “Traditional Korean Poetry Criticism: Fifty sihwa [poems written in Chinese] chosen and translated by Richard Rutt.” In Transactions of the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 47 (1972): 105-143.