8 Part 2: Japan (East Asian Literature and Literary Criticism)

Daniel Baird

Next we turn to Japan. Because of anime, manga, and other pop cultural influences, this is probably the most well-known of the three East Asian literary traditions here in the US.

Throughout Japanese literary history, certain ideas are the most important. First, there is the idea that writing not only expresses feelings but a reader can experience those same feelings when reading. Second, there is an emphasis on beauty, especially the transitory nature of beauty. Finally, there is a Buddhist-tinged sense of introspection.

Before the Heian Period (794-1185), Japanese literature was written in Chinese; during the Heian Period, native Japanese writing systems of hiragana and katakana were developed. The Heian Period would also see the flowering of poetry, prose, and fiction written in Japanese alongside the continued writing of poetry and prose in Chinese.

Japanese writers were familiar with the important Chinese writers and their works, such as Selections of Refined Literature or Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian. The Selections became required reading for the Japanese ruling class in the Heian Period.

Major Influences on Literature

Just like with China, Confucianism and Buddhism are important influences on Japanese literature. (For an introduction on these see Part I: China.) Confucianism entered Japan and was adopted in the Heian Period, although it should be noted that this tradition was less important to writing in Japan than it was in China or Korea. The Tokogawa government during the Edo period adopted Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucianism, calling it Zhu Xi Studies. This became the cornerstone of education and helped develop the code of bushido (way of the samurai). Buddhism entered Japan through the Soga Clan, who were descendants of Korean immigrants. The Japanese monk Dōshō (629–700) and others founded Zen in Japan, where it became extremely influential in culture and literature.

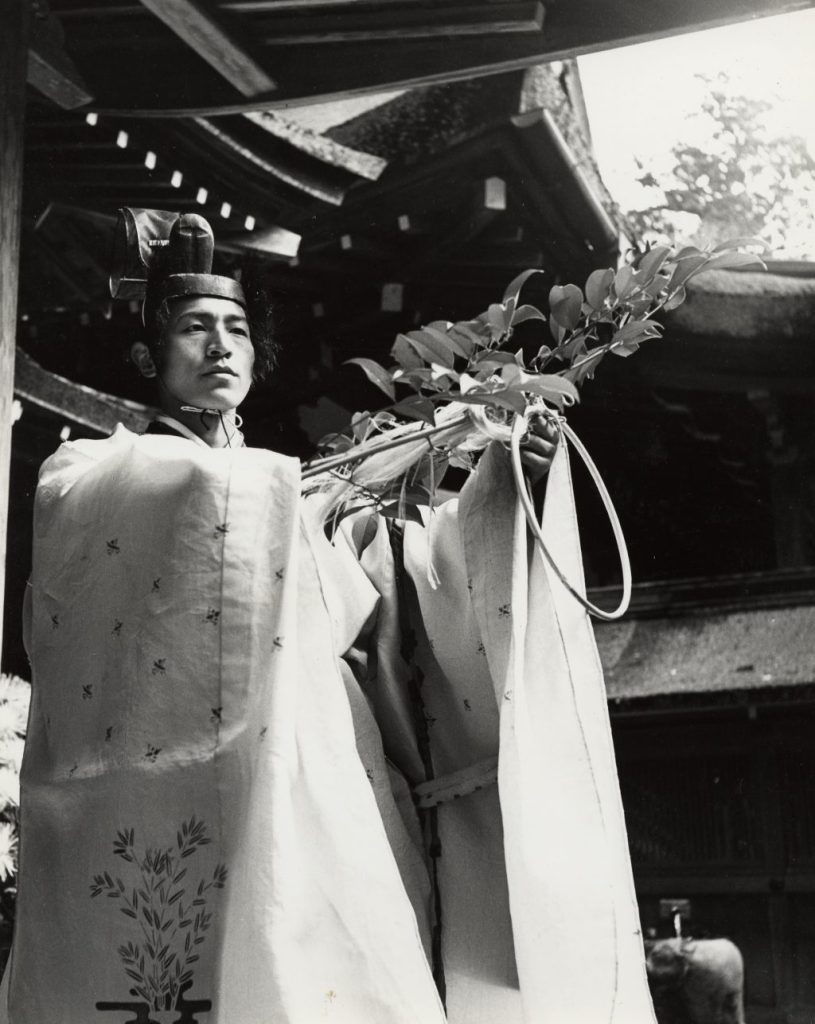

One of the constant influences on Japanese literature has been Japan’s own native religion, Shintō. There is no recognized founder for Shintō nor are there scriptures. The word “Shintō” translates as “the way of the gods” and refers to worship of kami. Kami are gods or spirits that are worshiped and enshrined in household, family, and public shrines. The most important are described in the Record of Ancient Matters (Kojiki) and the Chronicles of Japan (Nihongi), which are the two oldest mythological/historical records of Japan.

Part of Shintō is animism—the belief that objects, places, and all living things possess a spiritual essence or soul. For example, the negative feelings of a garbage dump that, over time, can create a supernatural creature that if not exorcised will bring misfortune on people. This leads to the emphasis on purity and ritual purification using salt or water (such as when sumo wrestlers purify the ring by sprinkling salt) or the purification ritual of harae, which can include the ōnusa wand that Shintō priests use during the ritual.

Other important ideas in Shintō include:

- no concept of duality between good and evil, instead emphasis on distinctions between pure and impure

- words have magic and affect people and events

- nature worship and the festivals that mark the seasons

Literary Themes and Ideas

Confucianism, Buddhism, Shintō, and to a minor extant Daoism, all contributed to literary values in Japan. Confucianism, especially Neo-Confucianism, saw literature as a model for morality and promoted the rational mind. This led to debates over form and creativity and created tensions between the emphasis on spontaneity with the need for artistic convention. And as with the literati of China or Korea, writers were expected to know the classics and anthologies—and this then led to the use of allusions and quotations that other literati were expected to recognize.

Buddhism often used literature as a form of reflection on the transitory nature of life. As part of this meditation one would concentrate on a detail that in turn stood for the whole—the blossom can represent the tree, which in turn comes to represent ideas such as nature or the sacred. Nature, along with purity, was heavily emphasized in Shintō.

Important Themes

- courtly elegance (miyabi): an elegance in speech and manners associated with the Heian Period, requiring that literature was decorous in language and subject while also avoiding vulgarity; this is also closely related to a sense of courtly or refined beauty.

- simplicity and spontaneity (shibui): praise for that which was the most simple or unadorned, leading writers to seek the appearance of spontaneity in their writings. A related idea was that of simplicity with subtle complexity, such as being able to see something such as a simple cup and learning something profound about it; this is a Buddhist-influenced concept.

- mono no aware: awareness of impermanence of things and therefore gentle sadness towards beauty knowing that it will pass; aware itself represents deep impressions felt by the reader or viewer.

- wabi–sabi: a Zen-influenced idea of contemplating and accepting impermanence and is expressed as an aesthetic in the imperfect or incomplete.

- yūgen: profound or sublime; comes from the idea that something that is only partially perceived and therefore invites the reader/viewer to contemplate beyond the superficial beauty.

Story Structure

For the four-part story structure commonly used in Japanese literature, see The East Asian Four-Part Plot Structure.

Another story structure is jo-ha-kyu, a three-part structure that originated in Noh drama. In fiction or drama, the story unfolds slowly at first, then gradually builds tension or speed with a very short resolution at the end.

In nonfiction, this means a paper may begin with what is unimportant and work towards the most important points at the end. Called tempura writing, one has to peel back the layers of what is unimportant to get to what is important.

Yet another structure is related to martial arts and the tea ceremony, but is also used in literature: shu-ha-ri. The first idea is “to obey” and refers to when a student is learning the martial art, such as its various forms. The second idea is “to break” and refers to when an advanced student is not merely learning forms, but also seeks understanding and ways to improve themselves. The final term is “to leave” and represents the obtainment of the martial art; this can be seen as when student becomes teacher. In Buddhist terms there is a progression from learning to detachment to enlightenment. For more on this see “The Meaning of Shuhari” on the Kimusubi aikido website. In literature, we see the progression of a major character, usually the protagonist, who goes through these stages as part of the story; today this is still very common in martial arts anime.

Honor

The idea of “honor” has been embedded in US pop culture for a very long time, but it really isn’t what you think it is. First, honor is NOT an overarching value in East Asian countries. Loyalty, benevolence, filial piety, and other Confucian values are all often just ignored and rewritten as the Hollywood concept of honor. Worse, this particular concept of honor originated in WWII propaganda against the Japanese and therefore is a racial stereotype.

American stories about samurai often emphasize honor, but the actual Japanese concept is called bushido, or way of the warrior. Bushido is more like a martial code of chivalry based on Neo-Confucian values and influenced by Buddhism. The samurai were considered higher in status than other people in Japanese society, and this contributed to how they saw themselves and how stories about them were told. Also be aware that the ideals of bushido changed over time.

So throw out Hollywood concept of honor and instead pay attention to what the stories actually teach in their values, whether Confucian, Buddhist, Daoist, or Shintō.

Watch this 15-minute video for more information: Asian Honor – Hollywood’s Gross Misrepresentation and WHY They Do It: https://youtu.be/giBmzgW-iOk

Some important ideas to bushido include:

- seeking spiritual enlightenment through martial arts (see shu-ha-ri above)

- it is class-based; samurai saw themselves as a higher class and could strike a commoner who had offended them

- samurai virtues include frugality, courage, benevolence, politeness, sincerity, filial piety and loyalty

- ritual suicide, revenge, and facing death are to be expected, but also important is proper etiquette

Some Important Authors and Works of Japanese Literature

Poetry

Poetry was the most important form of literary expression in Japan with an emphasis on lyric poetry. The earliest collection is contained in the Nara Period collection of waka[1] poetry, Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves. Poets also wrote in Chinese poetic forms with the earliest anthology of Chinese poetry by Japanese writers being the Nara Period Elegant Airs. The other early important anthology is the Heian Period imperial anthology, Collection of Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times. It contains two prefaces that define classical ideal of poetry: to express the poet’s heart or feelings and experience.

Nonfiction

There was a literary tradition in China, Japan, and Korea of what we call “miscellanies.” These works were collections of typically short essays on various topics. The idea was that the writing needed to appear as spontaneous as possible but at the same time very literate. One of the earliest in Japan was written by Sei Shonagon (c. 966- c. 1017), who was a contemporary of Murasaki Shikibu and served as a lady-in-waiting to one of the empresses. She wrote the delightful Pillowbook: a collection of thoughts, lists, ideas, etc., that give us insight to her world and her thoughts. A pillowbook was something that you kept under (or in) your pillow, sort of like a diary; it was very popular in the Heian Period. It is interesting to note that Lady Sei tells us that she used “leftover” paper from the imperial history project. Was she making some sort of statement about the importance of her writing?

Another famous work belonging to the miscellanies tradition is An Account of a Ten-Foot-Square Hut by Kamo no Chōmei (c. 1155-1216). Chōmei was a musician and poet who retired from court to be a monk. His Account is very short and delves into themes of the ephemerality of life by recounting earthquakes, famine, and the relocation of the capital. Chōmei also wrote a treatise on writing that included an important discussion on yūgen (see Literary Criticism below).

Essays in Idleness is the third famous work in the miscellanies tradition. Written by Kenko (d. 1350) after he retired (or was banished) from court, it contains his reflections on his life and on society. It has both Confucian and Buddhist themes and covers topics such as the pleasures of reading great books from authors of the past, the charm of tanka poetry, and the importance of withdrawing from society (a very Buddhist theme). It even references the Daoist writer, Zhuang Zhou.

The famous samurai Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) wrote The Book of Five Rings, one of many texts on martials arts for samurai. It is broken down into five parts or scrolls: earth, wind, water, fire, and then a very short final scroll expounding on the Buddhist concept of emptiness. These bushido texts established what we think of samurai today and are heavily influenced by Confucian ideals such as loyalty to one’s lord as well as Buddhist teachings (such as Musashi’s final scroll). These texts were written after a civil war during a relatively long period of peace.

In addition to the miscellanies, another popular form of nonfiction was the travel essay, although these essays were usually interspersed with poetry. The most famous example of this genre is the Narrow Road to the North, a prose work interspersed with haiku poetry that describes Matsuo Bashō’s (1644-1694) travels through Edo Period Japan. Bashō was a famous poet (see renku below) and he wrote five travel diaries, of which Narrow Road is the last and most famous. In these texts he muses on nature and describes famous spots that he visits. The diaries are infused with the Buddhist theme of impermanence.

Fiction

Unlike in China or Korea, fiction was held in much higher regard in Japan. The earliest novel The Tale of Genji is also one of the most famous in Japan. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu (c. 973-c. 1014), who was a contemporary to Sei Shonagon and like Sei was a lady-in-waiting to one of the empresses. The work owes much to earlier tales and from waka poetry collections, but it is a full novel, and it had a huge influence on Japanese culture. The story mainly follows Prince Genji and his search for the ideal woman. He finally takes a child – who interestingly shares the same name as the author, Murasaki – and raises her to be his wife. The characters are realistic and memorable, and the story gives fascinating insight to life in the Heian Period. Courtly fiction continued to be important for the next few centuries under the influence of the Tale of Genji.

The Tale of the Heike (1330) recounts the Genpei War (1180-1185) between the Taira and Minamoto clans for control of Japan. It recounts martial heroism through the lens of bushido, but it also emphasizes Buddhist concepts of impermanence and karma.

Short tales that later evolved into the novel form were also popular. These tales often included the supernatural and other wonders to draw the reader in. The oldest surviving written tale, the Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, is from the Heian Period. This story recounts how a bamboo cutter and his wife raise an orphan girl only to later discover she is in fact from the people who live on the moon. This story includes recounting trials for the orphan girl’s future husband, as are common to many tales around the world.

Tale literature continued to be popular going forward and included Buddhist collections of tales such as The Collection of Things Heard from the late Heian Period. There were also folktales both written and oral, such as the story of the fisherman Urashima Taro whose story contains the famous trope of marrying a beautiful woman who tells him not to do something (in this case the princess tells him not to open a treasure chest) and of course he loses her. It also is like the story of “Rip Van Winkle” in that Taro only spent 3 years with the princess, but generations have passed in his home village.

Ueda Akinari (1734-1809) wrote a collection of stories, Tales of Rain and the Moon that are retelling of Japanese and Chinese supernatural tales. Most of these tales are about encounters with ghosts, with a few exceptions about encounters with demons. These tales range from the sad reunion of a husband and deceased wife to encountering the white snake demon in the form of an alluring woman.

Drama

Kanami Kiyotsugu (1333-84) and son Zeami Notokiyo (1363-1443) were early important figures in Noh drama. Noh was especially developed because it had the patronage of the shogun and later daimyos as well; eventually the form was codified into five guild schools. The themes found in Noh are influenced by Shintō and Buddhism. Plays themselves are categorized into five groups where the main character is either a deity, a warrior, a beautiful young woman, a person who makes his way in life, or a supernatural character. Plays may include the supernatural such as gods, ghosts, and spirits. Noh often only has a main character and a secondary role and include musicians and a chorus. These plays use masks and costumes and are performed as ritual drama.

One famous Noh play is Breeze Through the Pines, known in its revised version by Zeami. It tells the story of a priest who takes shelter in the hut of two sisters. The sisters turn out to be ghosts and ask the priest to help them leave behind their attachment to the world so they can reincarnate. The title refers to lyrics from the drama, which state all that the two sisters left behind are the breeze through the pines.

Another form, Kabuki, stemmed from religious plays and became a popular entertainment associated with the entertainment district during the Edo Period (1600-1868). Kabuki is well known for its stylized costumes and distinctive face paint. At first actors performed improv on a rough outline of the play. Later Kabuki borrowed texts from Noh and puppet theate,r but the decline in puppet plays led to plays written specifically for Kabuki. The most important are the Eighteen Famous Plays, which were canonized in the late Edo period.

One of these Eighteen is Wait a Moment! Although it originally dates to early Edo, the characters and setting for the play only became set much later. The plot is very simple—an aristocrat desires the throne and kidnaps those who oppose him, including members of the imperial family. Just as he about to execute his prisoners, Kamakura Gongorō Kagemasa enters shouting, “Wait a moment!” and proceeds to rescue the prisoners. Kagemasa was a real military commander from the Heian Period.

Some forms of puppetry existed previously, but with the combination of written texts, chanting/singing, and musical accompaniment by shamisen, these traditions coalesced into puppet theatre in the Azuchi–Momoyama Period.

The most famous playwright was Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725), who wrote for both Kabuki and puppet theater, the latter of which made his reputation as the greatest playwright of Japan. Chikamatsu was from a noble family and was disowned when he became chanter for puppet plays. He also wrote historical romances and domestic or love tragedies.

A famous puppet play (that also came to be performed in Kabuki) is The Loyal Retainers: the story of 47 loyal samurai who, after their lord had to commit ritual suicide for assaulting a powerful court official, then sought revenge against that lord. This story is based on a true event that occurred in 1701.

Literary Criticism

The oldest book of literary criticism in Japan is the Mumyōzōshi (dating to the 1200s), by an unknown author. The book is divided into four sections: a preface, literary criticism, poetic criticism, and a discussion on prominent literary women. The Tale of Genji is one of the works it discusses, and both Sei Shōnagon and Murasaki Shikibu are in the section on women.

Ki no Tsurayuki (869-c. 946) led the compilation of the Collection of Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times, a Heian Period anthology of waka poetry (for more, see the section on poetry above). In the two prefaces Tsurayuki defined what would become one of the most important ideas in Japanese literature. He stated, “People, as they experience various events in life, speak out their hearts in terms of what they see and hear” (Ueda 3.). In other words, poetry expresses the feelings and experiences of the poet. Tsurayuki goes on to give us two critical terms for the study of poetry, words (or sounds) and feelings.

Words include things like form and conventions of the poem and the way to understand its formal structure. For example, a poem might have conventional phrases where an image conveys a particular meaning or emotion. Or a poem may employ a pivot word that can have more than one meaning and thus allows for multiple readings.

Feelings represent what a poet feels and experiences. Tsurayuki also points out that it is important to the response of the reader, as it helps create the idea that a refined person can relate to the emotions of the poet. Certain events such as seeing a plum blossom in spring or a desire to wish the emperor long life awaken the desire to create poetry. In fact, Tsurayuki says it is intense emotion that spontaneously creates the desire to create poetry. Therefore, a good poem can reproduce the original emotion. This means also that a good poem represents genuineness of feeling. In contrast, bad poetry comes from superficial emotion, or when a poet sacrifices emotion for form. This doesn’t mean that form isn’t important, however, because if the form is imperfect then the poem cannot convey the emotions the poet intended.

The next important contribution to literary criticism covered here comes from the playwright Zeami (Kanze Motokiyo c. 1363-c. 1443), who wrote some 20 essays on the Noh drama (see drama below). The first concept is imitation and representation in acting: the actor should find the true intent—for example, if a person is possessed by a deity then do not act out the possession, but rather act as the deity. Or if the actor is portraying a monk, then act out the deep devotion to religion. So the actor should not use false imitation. If an actor was able to properly represent what he was acting out, then Zeami referred to this ability as being able to affect the audience through the beauty of the form.

Another concept he explored in his writing was the term yūgen: a profound and mysterious sense of the sublime. Earlier it was a concept that was used to judge poetry contests, but in Noh drama it came to represent an elegant, graceful beauty in some ways not unlike the courtly beauty of the earlier Heian Period. What is different from courtly elegance is that beauty must yield to sadness, since beauty is fleeting.

For Zeami then, Noh drama came to represent the ideals of Zen Buddhism. Through Noh, one could contemplate the ultimate reality beyond what the intellect can understand.

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725) was also a playwright. He is most famous for his plays written for puppet theater and Kabuki, but he also wrote about his art. Like Zeami, Chikamatsu was concerned with representation—for him it was an internal motive, representation not just as an external copy of the action or a reproduction of a likeness. Chikamatsu thought that actors and puppets should be somewhat realistic but recognized that it should not be exactly the same. This is an aesthetic distance—if it is too close to reality, then it is not entertaining. Yet Chikamatsu was different from Zeami in that he thought that drama represented the human experience and emotion, not abstract ideas.

Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) was part of the late Edo Period (1600-1868) movement known as National Studies, which emphasized Japanese literature instead of Chinese writing and literature. Members of this movement rejected Neo-Confucian and the code of warriors (bushido). They also turned away from Buddhism because it rejected human feelings through teaching that people should reject attachments, including familial attachments. They were rigorously anti-intellectualism and wrote of limitations of mind—thus leading them to criticize both Confucianism and Buddhism for trying to know the unknowable or rationalize the irrational.

This rejecting of both Neo-Confucianism and Buddhism in favor of Shintō is easily seen through Norinaga’s ideas on literature. He stated that there is no didactic purpose to literature, nor should it be concerned with good or evil; instead, it should be concerned with true feelings. Literature expresses those feelings; poetry is rhythmical language while the novel simply describes those feelings in detail. Literature can thus nourish a person’s sensitivity to feelings and thereby draw closer to the Shintō gods. One of the reasons that Norinaga connects expressing feelings to Shintō is that he believes the intellect cannot create. The Shintō gods are creators and when a person is expressing their feelings by creating literature, they then draw closer to the Shintō gods.

Central to Norinaga’s literary criticism is mono no aware, or the awareness that things are impermanent and therefore the enjoyment of beauty is tinged with sadness that it will not last. Earlier ideas of mono no aware show that it was both refined and restrained. In contrast, Norinaga taught that it was unrestrained and spontaneous. He also built upon Tsurayuki’s ideas of the poet and the reader each responding to emotions by stating that if the writer expressed mono no aware through his writing and the reader was able to perceive that in the work, then both would share the feelings of pleasure and solace. This means that mono no aware not only defines what makes great literature but also becomes a mode of reception for the reader.

[1] Waka is an umbrella term referring to a short classical short poem written in Japanese rather than Chinese.

Further Reading and Resources

Japanese Literature & Aesthetics

Carter, Steven D. How to Read a Japanese Poem. Columbia University Press. 2019.

Hisamatsu, Sen’ichi. The Vocabulary of Japanese Literary Aesthetics. The Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, 1963.

Keene, Donald. Japanese Literature: An Introduction for Western Readers. Grove Press, 1955.

Keene, Donald. Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from the Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century. Henry Holt and Company, 1993.

Keene, Donald. World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1600-1867. Grove Press, 1976.

Miner, Earl. An Introduction to Japanese Court Poetry. Stanford UP, 1968.

The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature. Earl Miner, Hiroko Odagiri, Robert E. Morrell, eds. Princeton UP, 1985.

Ueda, Makoto. Literary and Art Theories in Japan. Center for Japanese Studies, 1967.

Bushido

Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) Book of Five Rings (described in appendix 1 under nonfiction)

Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933) Bushido: The Soul of Japan.

Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659-1719). The Book of the Samurai (Hagakure). [Author note: There is also a great manga edition in English of this book.]

Shintō

Ashton, W. G. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. 2 vols. Cosimo Classics, 2013.

Ono, Sokyo and William P. Woodard. Shintō: The Kami Way. Tuttle Publishing, 1962.

Philippi, Donald L. Kojiki. U of Tokyo Press, 1968.