How to Read Drama

Stephanie Maenhardt

The word theatre comes from the Greeks. It means the seeing place. It is the place people come to see the truth about life and the social situation. The theatre is a spiritual and social X-ray of its time. The Theatre was created to tell people the truth about life and the social situation.

–Stella Adler[1]

Introduction

If, as Shakespeare said in As You Like It, “All the world’s a stage, / And all the men and women merely players. / They have their exits and their entrances, / And one man in his time plays many parts,”[2] then reading and understanding drama should be an easy task, right? By these standards, we are all actors, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we are all experts at reading or understanding drama/plays.[3]

A play is meant to be experienced, seen, and performed. It is a “a composition in prose or verse presenting in dialogue or pantomime a story involving conflict or contrast of character, especially one intended to be acted on the stage.”[4] As a result, the solitary act of reading the text of a play can be a tedious and confusing process. But never fear, there are ways to approach reading drama which can help you discover the beauty, emotion, and action which live in this genre.

As Emilie Morin, a Professor of Modern Literature at the University of York, has noted, while seeing a live or taped production of a play can help us envision the emotions, meaning, and action of the work, “it is not necessary to have seen a performance of a play to understand its nuances and details.”[5] In fact, she argues, seeing a performance can change an individual’s reading of the text because performances “add some elements to a playtext [sic] and take other elements out of it.”[6] In other words, watching the movie is not the same as reading the play!

So, then, how can you approach a play so you cannot just understand the text, but also form your own opinions first before you search out a performance to see how others have interpreted the dramatic work? A play/dramatic work is:

- a written document that is meant to be seen or performed

- a collaboration between many different individuals, from the author/playwright, actors, and director to the set and costume designers, makeup artists—and, of course, the audience and/or readers

- a living text because so many individuals are involved in producing a play—because a production is a dynamic collaboration (see notes above) of voices, talents, and ideas, an author may give up some measure of control over their actual written words; the director’s staging, for example, may not necessarily be what the playwright had originally imagined for their work[7]

Because of the inherent ties which drama has to live performance and other audio-visual elements like costuming, set design, and musical accompaniment, approaching the task of reading the written text of a play can be a challenge. A live dramatic performance, unlike the written text of a poem, novel, or short story, must be consumed in a single sitting. You can’t pause or rewind a live performance and, unless a recording is made of the performance (like the original Broadway cast performance of Hamilton on Disney+), you can’t come back to re-watch the event. You must learn how to interact with the text in diverse ways and employ your personal sense of imagination to create what technicians, costumers, and soundtrack artists have created.

It can be helpful to remember that, much like the genres of fiction and poetry, drama also uses literary elements such as:

- Plot

- Characterization

- Setting

- Theme

- Symbolism

- Imagery

- Point of View

Even though you interact with a live performance differently than you do the written text of a play, you can still use these literary elements to help you uncover and understand some of the deeper meanings behind the text of the play.

Reading Drama: You Take Control

Theatre is a mirror, a sharp reflection of society.

–Yasmina Reza[8]

When you focus on reading the written text of a play vs. watching a live production, you step into the role of director, set designer, costumer, and actor all at the same time. By removing all the external “production filters,” you use your own rhetorical situation[9] and critical lenses to study the language of the written text, paying careful attention to the playwright’s word choice, including the symbolism and imagery of the text.

Reading the words on the page also gives you full control to pause the action of the play as you focus and revisit any parts that were confusing. This is something you don’t get the chance to do when you see a production on the stage. Can you imagine going to see Hamilton or King Lear on Broadway and standing up mid-performance to ask the actors to stop and go back two scenes because you missed something? The horror, the horror!

So, what do you look for when you are reading a play? The following six steps give you some general ideas to consider when you are focusing on the page, not the stage.

- Read for yourself, closely and carefully. This gives you a chance to really focus on the tone of the play. You can “listen” for emotion behind the lines. For example, does the playwright’s word choice make you think about love, anger, frustration, or sadness?

- Read as if you were preparing for a performance. Try reading some of the lines aloud to yourself, or to others. You might consider watching a YouTube video of the play being performed as you follow along with the written text.

- Try to visualize the scene. The scene = the staging of the play. In other words, imagine how the setting might look if it were being performed onstage. Looking at the stage directions, little notes from the playwright about who is speaking, where the scene takes place, etcetera, will help you here.

- Consider the “4th wall.” This is an invisible curtain which separates the play’s onstage action from the audience. If an actor or playwright “breaks” this wall, that means they are somehow reaching out to connect directly with the audience.

- Try to envision the action. What is happening on the stage? Is the character delivering a soliloquy (a solo speech that only they and the audience can hear, like the famous “to be or not to be” speech in Shakespeare’s Hamlet)? Are they having a conversation with another character (like Mrs. Hales and Mrs. Peters in Susan Glaspell’s one-act play Trifles)? Is there a fight sequence or a dance/party scene (like West Side Story/Romeo and Juliet)?

- Pay attention to non-verbal elements. Does the playwright give you any clues about how the characters are acting/moving or the gestures they are making? Does the text of the play include any specific descriptions of the scenes/setting?

- specific gestures or movements the characters should make, including actions such as running, sleeping, fighting, reading, facial expressions, etc.

- character notes to emphasize emotional/psychological states including whether a character was angry, jealous, ambitions, meek, happy, confused; notes might also include the character’s tone of voice

- location/setting (city, country, battlefield, bedroom, kitchen, library, etc.)

- musical accompaniment/sounds, including whether the sound was coming from the action right onstage or is heard in the wings offstage

- costuming (this helps to illustrate the character’s station/role within the action of the play—peasant or royalty, fool/clown, scholar/lover, etc.—as well as other aspects of their appearance; are they wounded in battle, wearing a disguise, etc.)[12]

Directors and actors use stage direction to prepare to bring the play and its characters to life on the stage. As readers, we can also use these stage directions to help engage our imaginations as we work to interpret the written text of a play.

It is interesting to note that while Shakespeare was among the first playwrights to include stage directions in the text of his plays, those original directions have been edited and revised many times to update the language, clarify references, etc. Starting in the 19th Century, it became more commonplace for playwrights to include detailed stage directions, especially at the beginning of a play, to help directors, actors, and readers know how the playwright envisioned their work. In “Stage Directions and Drama Terms,” Michael J. Cummings uses the openings for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House as examples of this difference:[13]

Romeo and Juliet

Enter Sampson and Gregory, with swords and bucklers, of the house of Capulet.[14]

A Doll’s House

[The action takes place in Helmer’s house.]

[SCENE.—A room furnished comfortably and tastefully, but not extravagantly. At the back, a door to the right leads to the entrance-hall, another to the left leads to Helmer’s study. Between the doors stands a piano. In the middle of the left-hand wall is a door, and beyond it a window. Near the window are a round table, arm-chairs and a small sofa. In the right-hand wall, at the farther end, another door; and on the same side, nearer the footlights, a stove, two easy chairs and a rocking-chair; between the stove and the door, a small table. Engravings on the walls; a cabinet with china and other small objects; a small book-case with well-bound books. The floors are carpeted, and a fire burns in the stove. It is winter.

A bell rings in the hall; shortly afterwards the door is heard to open. Enter NORA, humming a tune and in high spirits. She is in outdoor dress and carries a number of parcels; these she lays on the table to the right. She leaves the outer door open after her, and through it is seen a PORTER who is carrying a Christmas Tree and a basket, which he gives to the MAID who has opened the door.][15]

When you consider live theater, it is important to remember that theatrical license is often readily applied to even extremely specific stage directions, and you can end up with amazing productions of The Merchant of Venice set on 1990s Wall Street (Royal Shakespeare Company, 1994) or see The Taming of the Shrew re-envisioned for the big screen as 10 Things I Hate About You (1999). Of course, this happens with literary texts outside of Shakespeare/drama too, such as Jane Austen’s Emma which was re-envisioned for the big screen as Clueless. Other texts such as Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables and Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera have also been adapted for both the stage and the big screen. While these last three examples are works of fiction rather than drama, it’s still important to note the dramatic license taken as they’ve undergone the transformation from written word to live/film productions.

Drama on the Page vs. Drama on the Stage

When you come into the theater, you have to be willing to say, “We’re all here to undergo a communion, to find out what the hell is going on in this world.” If you’re not willing to say that, what you get is entertainment instead of art, and poor entertainment at that.

–David Mamet[16]

If you decide to watch a film production of a play, be aware that movie directors will exercise a great deal of creative license as they create their vision of the play, resulting in something that can be vastly different from the original written text. It is important to consider what has been cut and/or added and think about how this alters your interpretation of the play.

For example, Franco Zeffirelli’s 1990 film version of Hamlet starring Mel Gibson as the title character combined scenes and cut out many minor characters to create a traditional feature-length film. Six years later, Kenneth Branagh directed and starred in the first unabridged film version of Hamlet, holding true to the original text of Shakespeare’s play. The results were two films that approached the play in similar ways but were around two hours long (Zeffirelli) vs. just over four hours long (Branagh).

Theatre critic Charles McNulty spoke about the challenges of critiquing the production of a play vs. the original written text in a 2007 article he wrote for the Los Angeles Times. “Separating the player from the play,” he noted, “is never easy,” especially since the relationship between plays (written text) and performance (stage/film) involves so many different factors. The way a play is staged and who is cast in the different roles can have a huge impact on how an audience (readers) experience the work. “Great actors, like great critics,” McNulty noted, “can make you alert to shades of meaning and color that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.”

A play asks to be imagined and gives this right to everyone. A play has many lives beyond the page – not simply on stage, but in the minds of its readers. You are one of them.

– Emilie Morin[17]

Freytag’s Pyramid

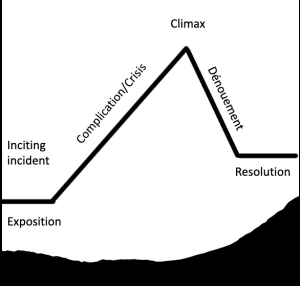

Another helpful tool to consider when reading plays is known as Freytag’s pyramid. Gustav Freytag was a 19th Century German playwright and novelist. He created a visual representation of dramatic structure which focused on key elements which he considered necessary to storytelling: exposition, inciting incident, complication, crisis, climax, dénouement, and resolution.[18]

So how do plays follow Freytag’s traditional dramatic structure?

- Exposition – explaining the action and introducing the characters/conflicts

- Inciting Incident – a character reacts to something that has happened

- Complication/Crisis – tension, some sort of problem that appears for the action/characters

- Climax – when the complication finally comes to a head, perhaps in a battle or argument

- Dénouement/Falling Action – explanation when things come together and move towards resolution

- Resolution – The End (Keep in mind that not all resolutions are “happily ever after.”)[19]

Critical Questions to Ask About Drama

Reading drama is an exercise in critical thinking, and learning how to ask questions is a valuable tool in helping you unpack the meaning and content of a play. Jessica Fries-Gaither, an education resource specialist with Ohio State University, notes that

Asking and answering questions while reading is essential for comprehension. … Asking questions before reading helps students access and use their prior knowledge as they construct meaning from a text. Asking questions while reading fosters active engagement with the text, and questioning after reading can be used to check for comprehension and encourage the transfer and application of knowledge.[20]

So, what are some questions we can ask when we’re reading drama? Stephen C. Behrendt, Professor of English at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, suggests asking questions about plays in the following categories:[21]

- Characters

- Setting

- Structure

- Language

- Theme

These five broad areas cover important moments in any literary text, but applied to drama they can help you dive deeply into the text to better understand it. Here, then, are just a few ideas to help you understand and critique drama:

- How many characters are there in the play? What are they like? Does the playwright give us any clues about their background, thoughts, emotions, etc.?

- Who are the main characters of the play? Who are the minor characters? How do they interact with each other?

- Where does the play take place? Does the playwright include any stage directions to help you envision the setting?

- What is the structure of the play (see the discussion of Freytag’s Pyramid below)?

- What is the main conflict? Is it resolved during the play? If so, how?

- Consider the language of the play. Is it realistic? Do you understand it (e.g. Shakespeare’s use of English vs. the style of English found in Susan Glaspell’s short play Trifles)?

- What is the main theme of the play? How do elements like characters and language represent/influence the theme?

- Are there any subplots? What are they? Who is involved? How do these subplots enhance the main action of the play?[22]

Characters in Drama

In displaying the psychology of your characters, minute particulars are essential. God save us from vague generalisations [sic]!

–Anton Chekov[23]

The protagonist is one of the main characters. They often have a tragic flaw or make a fatal mistake (e.g. Thor in The Avengers films or Bilbo Baggins from The Lord of the Rings saga) and can either be a hero or anti-hero.

The antagonist is another main character, one who fights against the protagonist and often tries to make them fail (think Loki in The Avengers or Voldemort in the Harry Potter series).

Plays also include a wide range of minor characters, often called flat or static characters or foils to a main character, who are there to provide background contrast and often help to develop the storyline for the main characters (e.g. think about all the extras/background characters you have seen on screen in films or TV shows). These minor characters may not have a key role—or even a speaking part in the play—but they help to create the mood of the scene and even draw more attention to the actions and mood of the main characters.

Dramatic Genres[24]

Theatre is the art of looking at ourselves.

–August Boal[25]

There are many distinct types of plays, but we will address four of the most common genres here. Note that the plays listed below could appear on more than one list.

The first dramatic genre we’ll look at is comedy. Meant primarily to entertain an audience, this style of drama has a lighter tone and a happy conclusion. Consider the following plays:

- Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

- The Curious Savage by John Patrick

- Harvey by Mary Chase

A second dramatic genre is tragedy, which engages the audience and teaches lessons using darker themes like death, greed, and destruction. The protagonists in tragedies often have a tragic flaw that leads to their downfall.

- Antigone by Sophocles

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare

- Trifles by Susan Glaspell

- Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller

- Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry

- After Easter by Anne Devlin

As its name suggests, tragicomedy is a dramatic genre which combines elements of both comedy and tragedy to create a serious drama which also includes moments of lighter comedy.

- The Winter’s Tale by William Shakespeare

- The Rover by Aphra Behn

- The Way of the World by William Congreve

- The Women by Clare Booth Luce

- Uncommon Women and Others by Wendy Wasserstein

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard

Melodrama is an exaggerated form of drama with one-dimensional, flat characters. It is important to note that melodrama can apply to both plays and individual characters/scenes within a play. For example, the term is often applied to situations where actors either over-acted or badly acted their roles, resulting in a portrayal that differed from the original intent of the playwright. Additionally, the kairos/conventions of the period when a play was written or first produced can often appear melodramatic to more modern audiences.

- The Tempest by William Shakespeare (while the entirety of the play might not be classified as a melodrama, some of the characters are melodramatic)

- Pygmalion by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (George Bernard Shaw also created a play by the same name which was later adapted into My Fair Lady for the big screen)

Situating Drama Within the Realm of Culture

An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell, because nobody else in the world can tell, what it is like to be alive. All I’ve ever wanted to do is tell that, I’m not trying to solve anybody’s problems, not even my own. I’m just trying to outline what the problems are.

– James Baldwin[26]

As this quotation from Baldwin infers, every literary work, no matter its genre, is part of a larger social context. Indeed, it is the duty of the playwright/author/artist to draw from the world around them, shining a light on social issues and events through the texts they create. Drawing on the idea of kairos,[27] literary texts are both part of the culture in which they were written and produced, and part of the cultures in which we read them.

Indeed, literary works often critique the society of their times by attaching or criticizing social values, traditions, and beliefs. For example, Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun is a powerful critique of racism and socio-political structures in the mid-20th Century United States. Additionally, one might successfully argue that the issues Hansberry addresses in her play (e.g. racism, discrimination, gender roles, abortion, economic disparities between racial groups) are just as pertinent today as they were when the play premiered.

In other words, it is possible for a play to be both a product of its culture, as well as a contribution to or reflection of that same culture, not to mention of the culture of anyone who reads or sees it.

Connecting to Drama Through a Critical Lens

One way to interpret a dramatic text is through the lens of literary/critical theory. As Vince Brewton, Professor of English at the University of North Alabama, notes in an article for the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the terms literary theory and critical theory are sometimes used interchangeably and are even “undergoing a transformation into ‘cultural theory’ within the discipline of literary studies.”[28] Brewton notes that regardless of the title applied to the practice, it is a framework of sorts, a “set of concepts and intellectual assumptions on which rests the work of explaining or interpreting literary texts.”[29]

It is important to note that there is a difference between literary theory and schools of criticism. Brizee and Tompkins note in their contributions to “Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism” for the Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) that the different schools of criticism are unique “lenses [readers] use to view and talk about art, literature, and even culture.”[30] These critical lenses “allow [readers] to consider works of art based on certain assumptions within [a particular] school of theory.”[31] As we see here, readers can use literary theory as a critical lens to focus their attention on specific aspects of a text, in the case of our discussion here, a drama/play.

An article for the online forum Pediaa expands on the ideas of the Purdue OWL, noting the inherent differences between literary criticism and literary theory. It reads: “Literary criticism is the study, evaluation and interpretation of literature whereas literary theory is the different frameworks used to evaluate and interpret a particular work. … Literary Criticism is the practical application of literary theory. Literary Theory is a combination of the nature and function of literature and the relation of text to its author, reader, and society.”[32] Basically, then, literary criticism is the act of using a specific literary theory as a lens through which to read and/or reinterpret a text.

The differences between theory and criticism here might seem slight; however, they are important, especially when you consider that it is natural to first engage with literary texts from an individual reader-response perspective. Prominent starting in the 1960s and continuing to the present day, a fundamental tenet of Reader Response Criticism is that it “considers readers’ reactions to literature as vital to interpreting the meaning of the text.”[33] In other words, your views and ideas as the reader/audience matter and help to create the meaning of a play.

Where this all gets a wee bit complicated is that while reader-response is, in and of itself, tied to one’s own reactions to or thoughts about a play, at the same time it can also intersect with other critical approaches to reading and interpreting the text. For example, write Brizee and Tompkins, a “critic deploying reader-response theory can use a psychoanalytic lens, a feminists [sic] lens, or even a structuralist lens.”[34] Literary theory, then, is the vehicle we use to practice literary criticism, uncovering new layers of meaning in a text.

While applying literary criticism to a play might seem a bit confusing at first, it is one way to really peel back the layers to get to the heart of the writing. In critical terms, we would call this deconstruction, the idea that “unified truth” does not exist, and we need to look for meaning in other places (i.e., the “margins” of a text.)[35] Through this theoretical lens and others, readers start asking questions about how the meaning of a play is made and where we look for it. Different critical lenses will yield different results, ever-expanding and nuanced interpretations of the same literary text.

Let’s Practice: Susan Glaspell’s Trifles

First produced in 1916, Glaspell’s play is loosely based on the 1900 murder of “John Hossack, which Glaspell reported on while working as a journalist for the Des Moines Daily News.” In 1917, Glaspell turned her play into a short story, called “A Jury of Her Peers.” As early feminist texts, both Glaspell’s play and the short story version which followed contrast “how women act in public and in private as well as how they perform in front of other women versus how they perform in front of men.”[36]

Exercise #1: Reading with a Critical Eye

Take some time to study the following excerpt from Glaspell’s play as you consider the following questions:

- What does this excerpt tell you about the symbolism of the play’s title, Trifles? Why do you think Glaspell chose to call this play Trifles? How might the title relate to the theme and plot of the play?

- How does the dialogue of the female characters differ from that of the male characters in this play? What does each group choose to focus on and why?

HALE: Well, my first thought was to get that rope off. It looked … (stops, his face twitches) … but Harry, he went up to him, and he said, ‘No, he’s dead all right, and we’d better not touch anything.’ So we went back down stairs. She was still sitting that same way. ‘Has anybody been notified?’ I asked. ‘No’, says she unconcerned. ‘Who did this, Mrs Wright?’ said Harry. He said it business-like—and she stopped pleatin’ of her apron. ‘I don’t know’, she says. ‘You don’t know?’ says Harry. ‘No’, says she. ‘Weren’t you sleepin’ in the bed with him?’ says Harry. ‘Yes’, says she, ‘but I was on the inside’. ‘Somebody slipped a rope round his neck and strangled him and you didn’t wake up?’ says Harry. ‘I didn’t wake up’, she said after him. We must ‘a looked as if we didn’t see how that could be, for after a minute she said, ‘I sleep sound’. Harry was going to ask her more questions but I said maybe we ought to let her tell her story first to the coroner, or the sheriff, so Harry went fast as he could to Rivers’ place, where there’s a telephone.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: And what did Mrs Wright do when she knew that you had gone for the coroner?

HALE: She moved from that chair to this one over here (pointing to a small chair in the corner) and just sat there with her hands held together and looking down. I got a feeling that I ought to make some conversation, so I said I had come in to see if John wanted to put in a telephone, and at that she started to laugh, and then she stopped and looked at me—scared, (the COUNTY ATTORNEY, who has had his notebook out, makes a note) I dunno, maybe it wasn’t scared. I wouldn’t like to say it was. Soon Harry got back, and then Dr Lloyd came, and you, Mr Peters, and so I guess that’s all I know that you don’t.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (looking around) I guess we’ll go upstairs first—and then out to the barn and around there, (to the SHERIFF) You’re convinced that there was nothing important here—nothing that would point to any motive.

SHERIFF: Nothing here but kitchen things.

[The COUNTY ATTORNEY, after again looking around the kitchen, opens the door of a cupboard closet. He gets up on a chair and looks on a shelf. Pulls his hand away, sticky.]

COUNTY ATTORNEY: Here’s a nice mess.

[The women draw nearer.]

MRS PETERS: (to the other woman) Oh, her fruit; it did freeze, (to the LAWYER) She worried about that when it turned so cold. She said the fire’d go out and her jars would break.

SHERIFF: Well, can you beat the women! Held for murder and worryin’ about her preserves.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: I guess before we’re through she may have something more serious than preserves to worry about.

HALE: Well, women are used to worrying over trifles.

[The two women move a little closer together.]

COUNTY ATTORNEY: (with the gallantry of a young politician) And yet, for all their worries, what would we do without the ladies? (the women do not unbend. He goes to the sink, takes a dipperful of water from the pail and pouring it into a basin, washes his hands. Starts to wipe them on the roller-towel, turns it for a cleaner place) Dirty towels! (kicks his foot against the pans under the sink) Not much of a housekeeper, would you say, ladies?

MRS HALE: (stiffly) There’s a great deal of work to be done on a farm.

COUNTY ATTORNEY: To be sure. And yet (with a little bow to her) I know there are some Dickson county farmhouses which do not have such roller towels. (He gives it a pull to expose its length again.)

MRS HALE: Those towels get dirty awful quick. Men’s hands aren’t always as clean as they might be.

Exercise #2: Applying Literary/Critical Theory to a Reading of Trifles

Using the excerpt of Trifles from “Exercise #1,” consider how critics from the following schools of literary criticism might interpret the text of Glaspell’s play. You might use the overviews of each theory on the Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism PDF from the Purdue OWL as a starting point for your analyses.

- Feminism OR Gender Studies

- New Historicism

- Post-Structuralism, Deconstruction & Postmodernism

Exercise #3: Stage Directions

When you approach the printed text of a play, stage directions are among the first written words you will encounter. Consider the opening stage directions for Susan Glaspell’s one-act play Trifles (see below). You have not read the entire play yet, but after looking at these notes, what do hints do they give you about the setting, as well as the emotions and motivations of the different characters?

[The kitchen in the now abandoned farmhouse of JOHN WRIGHT, a gloomy kitchen, and left without having been put in order—unwashed pans under the sink, a loaf of bread outside the bread-box, a dish-towel on the table—other signs of incompleted work. At the rear the outer door opens and the SHERIFF comes in followed by the COUNTY ATTORNEY and HALE. The SHERIFF and HALE are men in middle life, the COUNTY ATTORNEY is a young man; all are much bundled up and go at once to the stove. They are followed by the two women—the SHERIFF’s wife first; she is a slight wiry woman, a thin nervous face. MRS HALE is larger and would ordinarily be called more comfortable looking, but she is disturbed now and looks fearfully about as she enters. The women have come in slowly and stand close together near the door.][37]

- Adler, Stella. https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/stella_adler_284613 ↵

- Shakespeare, William. As You Like It, ii.vii.146-149, https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/as-you-like-it/read/2/7/ ↵

- For clarity’s sake, we’ll use the terms drama and play interchangeably throughout this text. ↵

- “Drama,” https://www.dictionary.com/browse/drama ↵

- Morin, Emilie. “Ways of Reading a Play,” https://www.york.ac.uk/english/writing-at-york/writing-resources/ways-of-reading-play/. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- This list is adapted from “How to Read Drama,” created by Stephen Housenick, Professor of English at Luzerne County Community College. https://academic.luzerne.edu/shousenick/104--DRAMA_ReadingDrama.ppt ↵

- Reza, Yazmina. https://www.azquotes.com/quote/753111 ↵

-

In his article, “Rhetorical Situation” for Open English @ SLCC, Justin Jory describes rhetorical situation as something which “refers to the circumstances that bring texts into existence. The concept emphasizes that writing is a social activity, produced by people in particular situations for particular goals. It helps individuals understand that, because writing is highly situated and responds to specific human needs in a particular time and place, texts should be produced and interpreted with these needs and contexts in mind.” When reading a play, you are always considering two distinct rhetorical situations. First is the rhetorical situation of the playwright, the context in which the text was created and produced. Second is your own rhetorical situation as a reader (audience member for live performances), the context in which you are approaching the play, including your own lived experiences and biases.↵

- Cummings, Michael J. “Stage Directions and Drama Terms.” 2003. http://shakespearestudyguide.com/Shake2/StageDirections.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Items on this list were adapted from Michael J. Cummings’ “Stage Directions and Drama Terms.” 2003. http://shakespearestudyguide.com/Shake2/StageDirections.html ↵

- Cummings, Michael J. “Stage Directions and Drama Terms.” 2003. http://shakespearestudyguide.com/Shake2/StageDirections.html ↵

- Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/romeo-and-juliet/read/ ↵

- Ibsen, Henrik. A Doll’s House. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2542/2542-h/2542-h.htm ↵

- Mamet, David. https://www.broadwayworld.com/people/David-Mamet/ ↵

- Morin, Emilie. “Ways of Reading a Play,” https://www.york.ac.uk/english/writing-at-york/writing-resources/ways-of-reading-play/ ↵

- Chey, Elizabeth. “Learning Freytag’s Pyramid …” Clear Voice. https://resources.clearvoice.com/blog/what-is-freytags-pyramid-dramatic-structure/ ↵

- Chey, Elizabeth. “Learning Freytag’s Pyramid …” Clear Voice. https://resources.clearvoice.com/blog/what-is-freytags-pyramid-dramatic-structure/ ↵

- Fries-Gaither, Jessica. Asking Questions All the Time.” 2011. https://beyondweather.ehe.osu.edu/issue/earths-climate-changes/asking-questions-all-the-time Emphasis added. ↵

- Behrendt, Stephen C. ” Some questions to help you study and understand Drama.” 2007. https://english.unl.edu/sbehrendt/StudyQuestions/Drama%20Questions.htm ↵

- Some of the questions on this list were adapted from Stephen C. Behrendt’s ” Some questions to help you study and understand Drama.” 2007. https://english.unl.edu/sbehrendt/StudyQuestions/Drama%20Questions.htm ↵

- Chekov, Anton. https://www.writerswrite.co.za/the-best-quotes-about-creating-characters/ ↵

- For more details about these dramatic genres and others, visit the Dramatic Genres page from SUNY Geneseo at https://www.geneseo.edu/~blood/Playwright3.html ↵

- Boal, Augusto. https://quotefancy.com/augusto-boal-quotes ↵

- Baldwin, James. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/9588490-an-artist-is-a-sort-of-emotional-or-spiritual-historian ↵

- "Kairos is knowing what is most appropriate in a given situation … think of it as saying (or writing) the right thing at the right time.” Pantelides, Kate. ”Kairos.” Writing Commons. https://writingcommons.org/article/kairos-2/ ↵

- Brewton, Vince. ”Literary Theory.” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/literary/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Brizee, Allen and J. Case Tompkins, contributors. ”Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism.” Purdue OWL. 2014. https://mseffie.com/assignments/heart_of_darkness/Purdue%20OWL%20Literary%20Theory.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Hasa. ”Difference Between Literary Criticism and Literary Theory.” 2016. Emphasis added. https://pediaa.com/difference-between-literary-criticism-and-literary-theory/ ↵

- Brizee, Allen and J. Case Tompkins, contributors. ”Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism.” Purdue OWL. 2014. https://mseffie.com/assignments/heart_of_darkness/Purdue%20OWL%20Literary%20Theory.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- ”Trifles.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trifles_(play) ↵

- Glaspell, Susan. Trifles. http://www.one-act-plays.com/dramas/trifles.html ↵