Children’s LITERATURE: A Human Experience to Be Reckoned With

Ron Christiansen

Introduction: A Case Study

Over 500 million copies of the Harry Potter series have been sold. The series is the best-selling fantasy series and the best-selling book series of all time. It may be impossible to overstate the impact of the Harry Potter series on book reading in general and in creating a communal reading phenomenon specifically. And the impact reaches far and wide and even close to home in ways no one could have imagined. In July of 2007, as reported in the Deseret News,

Pottermania hit Utah hard Friday evening with only hours before the much-anticipated release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the seventh and final volume in the Harry Potter series. … Fans around the state joined in the melee with magical release parties culminating with the distribution of the book. Bookstores and libraries transformed into Diagon Alley, the Leaky Cauldron and classrooms from Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. (Walquist)

It’s simply a fact that scores of young readers, and some not so young, participated in one of the greatest book clubs in world history. In my own teaching, this series is referenced by students with a ferocious passion more than any other.

Yet many critics in the establishment of English LITERATURE (pronounced with a highbrow British accent) have deemed Harry Potter nothing more than a comforting childish story. In “Harry Potter and the Childish Adult” A.S. Byatt, English critic and renowned novelist, insists that “Ms. Rowling’s magic world has no place for the numinous. It is written for people whose imaginative lives are confined to TV cartoons, and the exaggerated … mirror-worlds of soaps, reality TV and celebrity gossip.” And one of the most famous literary critics of the modern era and defenders of the canon, Harold Bloom — in “Can 35 Million Book Buyers Be Wrong? Yes.” — couches his critique of the Harry Potter series in his disdain for children’s literature as a whole: “I read new children’s literature, when I can find some of any value, but had not tried Rowling until now.” Ouch. It’s as if he is talking about a chicken sandwich at a new fast casual restaurant!

These critiques from on high should not be surprising as Harry Potter has at least three strikes against it from the perspective of the gatekeepers of great LITERATURE. One, it is hugely popular; two, it is a series written for children; three, it is genre fiction, namely fantasy. Genre fiction is defined as a type of fiction that fits into a category that follows a certain formula and has repeating tropes or characteristics, e.g. horror, mystery, romance, science fiction.

It may come as a surprise to some readers that these three strikes would work against a book series. But for many in the literature business there is a clear distinction between literary fiction and genre fiction. As Sean Glatch posted, “The world of fiction writing can be split into two categories: literary fiction vs. genre fiction. … [The first] is character-driven and realistic, whereas genre fiction describes work that’s plot-driven and based on specific tropes.” But Glatch quickly admits this binary does not reflect the real experience of literature and is unfair to both genres.

Ultimately, I don’t buy into the reasoning of the gatekeepers of LITERATURE. Instead, I believe all genres, including children’s literature, are part of the human experience we must reckon with through nuanced reviews, tough conversations, and messy evaluations that do not rely on easy binaries.

How has viewing children’s literature as part of this binary created damaging assumptions? And if we break down these assumptions using the Harry Potter series, what might we learn about children’s literature as a whole?

Defending Children’s Literature

Hintz and Tribunella, in Reading Children’s Literature: A Critical Introduction, start their introduction chapter to students by identifying common assumptions. The first assumption they list is “Children’s literature is too simple and obvious to be read critically” (28). Identifying assumptions is a common move in textbooks for children’s literature and in the broad conversation about children and the books written for them. Another common move in these textbooks is to wrestle with how we delineate what should count as children’s literature: Books actually read by children? Books labelled as children’s literature? Books with children as protagonists? It gets complicated. More on this problem of definition later.

Defending children’s literature, Elizabeth Law, a children’s book editor at Viking contends, “‘Many writers assume that because children are smaller, and their books are smaller, that children are less complex, easier to please — and therefore easier to write for’ … [but] for an adult to write for children, which usually involves writing simultaneously for adults, requires the kind of intellectual and creative gymnastics that cannot be described as ‘easy’” (qtd. in Hintz and Tribunella 28). Of course, it is not difficult to find contradictions to these assumptions about children’s literature. The fifth book in the Harry Potter series, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, is the longest, the US version coming in at 870 pages. And children were and are reading the series. My oldest son at age seven read them. And I read the entire series to my youngest son, except on nights when I tired too quickly for his appetite for story, so he stayed up longer to slowly read a few more pages.

But, of course, there are shorter books that are considered children’s literature, lots of them and many that are quite visual in nature. Yet these books, children’s literature scholars would argue, are also complex. If we build a case for Harry Potter, we also build a case for all of children’s literature and for genre fiction written for adults. As indicated by Law, all children’s literature has a certain level of complexity as the writer must envision and write for at least two audiences: children but also the adults — librarians, teachers, parents, grandparents — who will most often purchase or guide children to these books.

Stephen King to the Rescue … in most things[1]

And who in the world of novel writing might come to the rescue of children’s literature in general and the Harry Potter series specifically? Stephen King, the King of genre fiction. And his inclusion here in an article about children’s literature highlights our earlier discussion of the difficulties of defining what counts as children’s literature. Why? Because many children and young adults read King even if he is not explicitly writing for children.

After the last book in the Harry Potter series was published, King pushed back on these critiques:

The bighead academics seem to think that Harry’s magic will not be strong enough to make a generation of nonreaders […] into bookworms … but they wouldn’t be the first to underestimate Harry’s magic: just look at what happened to Lord Voldemort. And, of course, the bigheads would never have credited Harry’s influence in the first place, if the evidence hadn’t come in the form of bestseller lists. A literary hero as big as the Beatles? “Never Happen” the big heads would have cried. “The traditional novel is as dead as Jacob Marley![2] Ask anyone who knows! Ask us, in other words!”

And King doesn’t stop at pushing back on the literary establishment, but also offers a detailed analysis of the Harry Potter series: “Her characters are lively and well-drawn, her pace is impeccable, and although there are occasional continuity drops, the story as a whole hangs together almost perfectly over its 4,000-plus page length.” It would seem Byatt and Bloom are reading a series of books unknown to King. Their response couldn’t be more different.

In King’s defense of the Harry Potter series, we find an argument for children’s literature and for children as autonomous readers and beings. King ends by quoting the musical band the Who: “The kids are alright” because they have authors like J.K. Rowling who tell effective stories without looking down on children.

Clearly King believes that the experience children have as readers is important — a human experience to be reckoned with.

Interlude

Even given all this evidence that the Harry Potter series is not considered literature, it may be difficult to garner much empathy. Clearly J.K. Rowling has much prestige even in some literary circles and a boatload of money. Ditto for Stephen King. But that is exactly what is so disturbing about this insipid and simplistic notion that LITERATURE can be easily identified by excluding large swaths of the literary world even when parts of these are written by white, now privileged, authors such as Rowling and King. If this can be done to them then how easily can so many other great books be dismissed simply because they are written for children or teens? So many amazing titles spring to mind …

M.C. Higgins the Great written by Virginia Hamilton in 1977. A book about an African-American family that lives in the Appalachian mountains where they are being encroached on by a coal company. It is a beautifully symbolic and BIG novel. An teenage boy grapples with his relationship with his mother, father, and the outside world.

If You Come Softly, seen as a romance novel written for young adults by Jaqueline Woodson: it is a profound novel of beauty and grace and terrible grief. An African-American teen, Jeremiah, starts attending an elite prep school where he falls in love with Ellie, a Jewish white girl.

American Born Chinese by Eugene Luen Lang, a powerhouse graphic novel layered in complexity, history, and searing humor that explore Chinese-American identity and stereotypes.

And I could go on and on, and hopefully readers can add their own titles here, but the point is if J.K. Rowling can be dismissed because her novels are written for children, how easy is it to dismiss other books written for children by BIPOC or other authors outside the mainstream?

Academics to the Rescue

Many scholars in the field of children’s literature argue that literature written for children has specific traits and can be identified. In fact, Perry Nodelman has stated that the act of defining what is children’s literature has been a significant activity for academics since its inception as a discipline (Hidden Adult 136). Following in that tradition of identifying characteristics, Hintz and Tribunella argue that because children’s literature is complex, it is then able to offer so much pleasure:

Children’s literature can reveal both our greatest pleasures and our deepest fears or concerns. Understanding what pleases or frightens us the most is absolutely key to understanding what it means to be human and how human beings relate to and treat one another. In evoking childhood memories, children’s literature provides access to our most foundational emotions or experiences; it is thus one of the few ways adults can maintain a connection to childhood. (38)

And the Harry Potter series does just this. While it is about wands and magic, it is also about boyhood, friendship, families and, ultimately, how to treat one another. These everyday struggles are meaningful and robust even if they are presented through a magical world that delights and entertains.

To fully embrace Hintz and Tribunella’s point, let’s take this as an invitation to revisit our own reading histories. In the children’s literature class I teach, I accomplish this through the Reading Autobiography assignment. Here I ask students to revisit their past by thinking back to their first memories of being read aloud to and their first experiences of taking charge of their own reading.

Early Reading Experiences to the Rescue

There are many firsts when it comes to reading …

Our earliest memoires of being read to by an older sibling or adult. I don’t have a clear memory of this for some reason, but the physical evidence of books from my childhood prove some reading happened. When I ask my mother, she tells me about Frog and Toad are Friends by Arnold Lobel. Looking up the cover, the memories flood back.

Or the first time or very early experience of reading a book on one’s own. I remember reading a short picture book about alligators my grandmother gave me where personal information such as your name and address were inserted into the actual story. I thought it was magic.

Or the first series we read. For me it was Alfred Hitchcock and The Three Investigators by Robert Arthur Jr. I can still feel the excitement of being in their hideout that was essentially underneath a junkyard where they figured out mysteries. At the time there were 34 books and I owned every title.

Or the first time when we read a book on our own that truly scared us. For me it was The Amityville Horror by Jay Anson. After 40 years, I can still see the flies filling up the window sill.

Possibly some first reading experiences have come to your mind while reading through this list. And maybe some of them tapped into strong emotions. It’s clear there are many books written for children that do engender our “greatest pleasures” or our “deepest fears.” Think of Charlotte’s Web, where Wilbur, the spring pig, faces death.

Or Coraline, a fantasy, where the main character meets her Other mother who has a button for an eye — deepest fear — but eventually after an arduous struggle returns to her parents’ loving embrace — greatest pleasure.

Or think of the Harry Potter series where Harry is orphaned and then repeatedly mistreated by the Dursley’s as the indulge their son Dudley.

Exercise: Exploring your reading history

Who do you remember reading a book to you? A parent, a sibling, a grandparent? Was it a pleasant experience? Was it at night or during the day? Were you bored or was it pleasurable?

When did you first read on your own? What decisions did you make as a reader and why? How did you find your books? (In my class I have my students find some of the books they read as children by digging them out of boxes of keepsakes or returning, if possible, to their childhood homes and also asking the adults in their lives who facilitated this reading.)

Hintz and Tribunella are arguing that in making this move to “provide access to our most foundational emotions or experiences” children’s literature is a powerful literature that helps to remind us what it means to be human. And isn’t this one of the basic traits of all good literature?

Making Literature

Nodelman and Reimer in The Pleasures of Children’s Literature contend,

“All readers and all people who discuss their reading are in the process of making literature, of making it mean more to themselves and to others” (27).

And isn’t that exactly what we have been doing together in this last section? That is remembering and talking about our reading as young children and in doing so making it literature. It is birthed as LITERATURE less because of an external rating of its worthiness and more through its socially constructed meaning. The Harry Potter series seems the quintessential example of a book being read by thousands, millions even, and then made through this process into literature. Nodelman and Reimer continue by insisting that this process includes children:

A child’s response to a poem, based on limited experience of both life and literature, may seem to be less complicated in some ways than the response of English professors. … But the children’s response may also be more complicated in other ways. It’s certainly no more and no less significant. … In being different, it adds to the possible meanings texts engender and thus enriches literature as a whole. (27)

If this is true then my own response as a 12-year-old to The Amityville Horror, a so-called true story of a family moving to their dream home where a young man had murdered his own family, “enriches” the world and builds onto the literature available to the world. And some would argue this remains true even if when I now, a teacher of 30 years, return to this novel and find it somewhat cliched and overly dramatic. Yet that original experience still feels immensely powerful and meaningful. I wrought the experience into being. I chose this book and then I chose to keep reading even though it frightened me. I chose to push through the fear in order to understand the mystery of the cloven footprints in the snow. Again, a human experience to be reckoned with, to be recognized and validated.

Persistent Hierarchies

It seems in most of our endeavors as humans we want to create a hierarchy that clearly establishes what is more valuable and should be respected and striven for. And this is clearly part of the literary world. Many write books, but few write LITERATURE. And for most of our literary history children’s literature has not been regarded as literature at all: at best instructional or silly, at worst childish or toxic. If one category is on top, then surely another must be on the bottom.

But if this is true then how do we explain these powerful reading experiences with simple books written for children or the foolish children reading fantasy or scary books well beyond their grade level?

In an attempt to level such hierarchies, Nodelman and Reimer compare the implied readers of a Mother Goose Rhyme vs. T.S. Elliot’s poem “The Waste Land.” They admit how different these implied readers are yet argue, “Readers can’t have a satisfying experience of either of these poems unless they’re willing and able to take on the role of the specific reader that each implies.” Therefore, the wonder that allows meaning and pleasure to come from both reading experiences are equally valid. Both are literature.

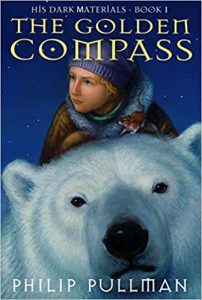

Nevertheless, somewhat embarrassingly, I recognize that I still buy into a hierarchy of sorts. Just because I agree with King that the Harry Potter series is great storytelling and definitely LITERATURE, I do not believe it the very best of fiction. In the abstract, yes, they are wonderful books with complex characters, amazing world-building, and thoughtful recurring themes, but if I force myself into a pragmatic decision by playing the “deserted island game” I often challenge my students with (i.e. you are headed to a deserted island and can only take three books with you), many children’s books would make my deserted island list before any of the books in the Harry Potter series. Even other fantasy series written for children would make it into my pack before J.K. Rowling: the adventures of young Lyra in The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman, part of the original His Dark Materials trilogy, has much more depth, for me, and is infinitely more re-readable than any of the Harry Potter books.

I would argue both books are literature, but we must still have nuanced debates about which books are most effective at engaging their audience and illuminating the world of human experience.

In “Is Harry Potter Classic Children’s Literature?” Daniel de Vise notes that some critics have also highlighted weaknesses in the Harry Potter books by comparing them to Pullman’s trilogy: “They can see where many of Rowling’s elements have come from and do not consider her story to be terribly original. Often, for those who are not totally enamored with Rowling’s craft, it was in comparison with other books. Philip Pullman and Diana Wynne Jones, for example, are cited as authors of novels that hit deeper in the heart, soul and intellect.”

And, even though this admission may harm my overall thesis that the Harry Potter books are indeed LITERATURE, I have to agree that some children’s literature books do “hit deeper” than the Harry Potter series. Sitting on my deserted island I would rather reread the adventures of the young Lyra in the transformed world of Oxford, England, than of Harry Potter escaping the muggle-world at Hogwarts.

But it oversimplifies to use these criticisms as an excuse to exclude Harry Potter from the realm of literature. That’s too easy. Instead young readers, teachers, and critics must stay engaged in the complex work of making meaning and evaluating the work of literature without simplistic judgements that condemn certain genres as outside the bounds of human experience.

And Yet …

To be honest, I have never reread any Harry Potter books since finishing them with my youngest son. Instead, they are collecting dust on bookshelves in our rarely used basement. And I probably won’t reread them again or even teach one in my children’s literature course. (Too many students have already read them!) Well, maybe I’d reread them if a future grandchild was interested.

And yet, I will continue to read children’s literature as LITERATURE long after I’ve retired and no longer teach a children’s lit class. I will do so because I want to read good books, books I see as worthy of a close reading and literary study that will also entertain and delight.

Works Cited

Bloom, Harold. “Can 35 Million Book Buyers Be Wrong? Yes.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 11 July 2000, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB963270836801555352.

Byatt, A.S. “Harry Potter and the Childish Adult.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 7 July 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/07/opinion/harry-potter-and-the-childish-adult.html.

Vise, Daniel de. “Is Harry Potter Classic Children’s Literature?” The Washington Post, WP Company, 16 July 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/college-inc/post/is-harry-potter-classic-childrens-literature/2011/07/16/gIQA0RS1HI_blog.html.

Glatch, Sean. “Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction: Definitions and Examples.” Writers.com, Writers.com, 11 Oct. 2021, https://writers.com/literary-fiction-vs-genre-fiction.

Hintz, Carrie, and Tribunella, Eric L. Reading Children’s Literature: A Critical Introduction. 2nd ed., Broadview Press, 2019.

King, Stephen. “Stephen King: The Last Word on Harry Potter.” EW.com, 10 Aug 2007, https://ew.com/article/2007/08/10/stephen-king-last-word-harry-potter/.

Nodelman, Perry. The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Nodelman, Perry, and Reimer, Mavis. The Pleasures of Children’s Literature. 3rd ed., Allyn and Bacon, 2003.

Spencer, Christian. “Heavyweight Authors Stephen King, J.K. Rowling Feud over Trans Women.” The Hill, The Hill, 21 May 2021, https://thehill.com/changing-america/enrichment/arts-culture/554777-heavyweight-authors-stephen-king-and-jk-rowling-feud/.

Walquist, Tammy. “Wizarding Fans Celebrate ‘Deathly Hallows’ Release.” Deseret News, Deseret News, 21 July 2007, https://www.deseret.com/2007/7/21/20031044/wizarding-fans-celebrate-deathly-hallows-release.

- More recently Stephen King has disagreed with JK Rowling’s tweets supporting “Maya Forstater, a tax researcher who was terminated from her job at the Centre for Global Development for questioning the process of gender transition on social media” as reported in “Heavyweight authors Stephen King, J.K. Rowling feud over trans women” by Christian Spencer ↵

- fictional character in Dicken’s A Christmas Carol ↵