Active and Mindful Engagement with Literature: A Practice for Reading

Andrea Malouf

Reading literature is already enjoyable on the surface level, through the stories of characters. But reading literature on a deeper level, using a more active and mindful approach, can help reveal even richer meaning that enhances the whole experience.

What is “active” reading?

The term “active reading” might seem redundant. Isn’t reading an action? Yes, it is, but unlike reading for just an experience or an immersion into a good story or poem, active reading of literature (sometimes known as close reading) is an engagement in literary analysis or the reading of a text with the purpose to understand and analyze the text based on deeper understandings of the text or different academic needs. This kind of reading engages the reader in active roles with the text, whether that is exploring the text from multiple perspectives, literary devices or overall meanings or themes.

What do I need to know before I read a literary text?

Active reading engages in initial knowledge of the text first. Active exploration of a text prior to reading could include exploring the author’s bio or concepts of the work. It might also include reading other literary analyses of the text. Understanding the author may help to understand their purpose or focus of the text(s), which can guide your own reading for context and purpose of the text.

Historical or cultural contexts—including socioeconomic, gender, environmental and even political attitudes of the time of the text’s production—can offer important understanding of the text. Likewise, as a reader, you may identify with a text based on your own experiences and understandings of the world when you are reading it.

The context also relates to our own reactions to a text based on our own experiences. This idea of reader-response theory (textual meaning occurs within the reader and their own unique experiences of the world) allows the reader to identify with the text on an emotional level based on one’s own experiences. Many literary texts and poems can be a year old or centuries old and still be an important record/narrative of the human condition at that time or aspects of that time and its cultural attitudes. And yet the textual meaning can become more personal for the reader based on one’s lens of personal experience.

Knowing the cultural time, setting and attitudes in which the text is set or was written also provides an essential context to the work, and may even add layers to its meaning. For example, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby was written in 1925 as a critique of the “American Dream,” as well as a critique of capitalism and class dynamics … and has been hailed as a sign of consumerism that led to the Great Depression, even though Fitzgerald did not anticipate the Great Depression. While the glamor and mystique written of this world in Great Gatsby might have seemed a criticism of the times (and a lesson to be wary of for future generations), Fitzgerald also most likely did not foresee that his book in modern contexts also reinforces sexist and misogynistic attitudes about women—attitudes that were not seen as necessarily contrary or hurtful in 1925, unlike current times.

The reader can extrapolate based on additional histories and one’s own lens of experience how a text may create a specific meaning while also undermining or challenging that meaning based on what the reader now knows about the ideologies of the text as they transcend times and situations. This may seem to create an impermanence of the author’s intended meaning, as meanings may multiply and extend throughout time and place with each new reader of the text. But isn’t that literature’s enduring quality?

How do I actively read?

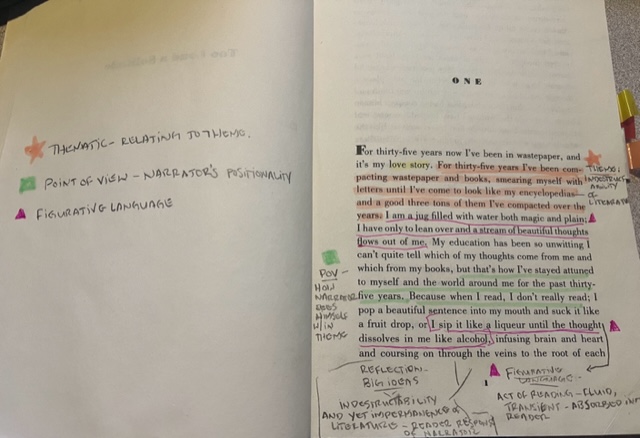

Active reading can be a physical engagement with the text, meaning actively highlighting, notetaking and reflecting while reading the text. This can be done in many forms, including annotation and journaling. Active reading is common in many areas of academic reading, some of which you may have experienced. If reading for information, for example, you might annotate the text and/or journal about key concepts. When actively reading literature, you might be looking for more nuanced ways the literary work is developed. Such an inquiry might include analysis of narrative devices used or the complexities of the text’s message and point of view.

What is Annotation?

Annotation refers to making notes on the pages of the text itself, for gathering information or identifying areas of interest. This is often done with active notetaking within the text or in the margins, and it can create more of a mental map for understanding the text.

Annotation techniques may be specific to each reader. Some techniques may include the following:

- Highlighting areas of the text: Highlighting can be done in print with colored markers or with digital tools in some electronic texts. You might consider highlighting areas of the text that resonate with you or that share a deeper meaning or complexity of the text. If you highlight all that is interesting, you might find you are highlighting a lot, but without a later reference of why that passage or sentence mattered to you at the time.

- Writing in the margins: Putting your own pen / pencil / digital typing tool to the text can create more context than highlighting alone. Perhaps you highlighted or underlined a meaningful section of the text; writing in the margins as to why that mattered or what it references can be helpful. You might notice poetic or literary devices used, or perhaps imagery or elements of character development. Whatever you are noticing, having a margin note or comment in the text can help you to remember later why that passage was relevant to your exploration. You might even develop an archive of symbols. For example, a star for character development or a circle for imagery might create a quick map needed to identify specific literary elements throughout the text. Whatever choices you make for annotation, the immediacy of writing in the text and in the margins can create a roadmap for later analysis.

- Knowing what to annotate for prose: Annotate for “small bits” and “bigger bits of literary analysis.” Later, you can reflect on how some of the more singular elements work with the larger elements to determine a more concrete interpretative analysis. Of course, if reading for class or an assignment, also refer to which specific elements are called for in the assignment.

“Smaller Bits” or More Singular Elements to Annotate

- Imagery/sensory details: How a setting, scene, character or even an observation by a character or narrator can highlight important elements of literary analysis.

- Symbols: A symbol may have a literal meaning or reference in the text but may also suggest or represent other meanings in the text. For example, in Jamaica Kincaid’s nonfiction novella A Small Place, the decaying library sign that states the year of remodel is a literal symbol of decay in front of a once magnificent colonial building. Neither the sign nor the building have had any updates since Antiqua became an independent state. The library sign as a symbol, with its note of pending remodel, then can be read as a symbol to the more egregious elements of post-colonial island impacts.

- Motifs: A motif is a recurring literary element that may include a symbol, concept, plot structure, imagery or other elements that surface repeatedly in the text. Their recurrence may point to a larger theme or allegory of the piece.

- Figurative Language: Figurative language does not use a word’s literal meaning, but instead creates a flourish or more dynamic way of thinking about an image, concept or idea. Figurative language can include such things as metaphor, simile, hyperbole, allusion and personification. Most are making comparisons or contrasts to the actual meaning or literal meaning. “Our love is like a rose” is an example of simile. “The seeds tore greedily through the earth” is an example of personification based on verb choice. Figurative language creates a more sensory and often deeper reading of the text’s characters, themes and point of view.

Expanding your repertoire of Literary Terms can offer multiple pathways for analysis.

“Bigger Bits” or Larger Elements to Annotate

- Character Development: You might note in your annotation certain characteristics or physical attributes of character or narrator that speak to their role or significance in the work.

- Plot: You might note twists of plot or what seems to be critical moments of the plot.

- Point of View: You might note elements of narration. Is this told in first person, second person or third person? Is the narrator a reliable narrator, an omniscient narrator or a narrator with a limited perspective?

- Theme: You might note thematic elements, or unifying elements that speak to a larger message or concept of the text. Themes often emerge from the close identification of symbols, motifs, point of view and other literary devices used in the text.

- Allegory: You might note allegoric elements that are representative of larger humanistic traits or a message in the story, such as bravery, greed or passion. Some allegories provide larger lessons or thematic concepts. For example, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde could be read as an allegory for one’s struggle to contain one’s inner primal instincts.

Again, explore additional Literary Terms and examples.

Imagine this active world of reading as signposts for how you might reflect, engage and then analyze these works. That might mean more analysis with a journal or some element of reflection.

What is a Reading Journal?

A reading journal provides a space for summary, analysis and reflection. You can use a reading journal to make notes while you read or after you read a portion of or a full text. Reading journals used in the following ways can be useful to track your ideas/analyses during and after your reading:

- Summary: Summarizing what you have just read has proven benefits for cognitive retention of the material read. For literature, you might summarize a portion of the plot, a character or even an overall arc of the text or poem.

- Analysis: Assessing how specific elements speak to overall themes or larger concepts (and vice versa) is key in analysis. For example, you might review the “small bits” of your annotation to see how imagery, figurative language, symbols and motifs are leading to larger conclusions about character development, plot, point-of-view, as well as thematic or allegoric concepts about the text.

- Synthesis: “Synthesis” is often defined as the action of combining separate elements to form a whole. One you’ve identified and analyzed the “small bits” and “bigger bits,” how do ll these aspects fit together to form a broader meaning of the text? Consider yourself an alchemist, transforming multiple elements of ideas into something more expansive and connective. Acquiring skills in synthesis can help you in other literary endeavors, too, such as writing about how two texts relate and speak to each other.

- Reflection: Bringing in your own lived experience as it might compare or contrast with characters and the story can enlighten your analysis and overall engagement with the text. A reader might relate to the more literal immigrant experience as told in Chimamanda Adiche’s story That Thing Around Your Neck, or a reader who has not had the experience of being a New American might also relate to the feelings of being an outsider or concepts of “otherness” that are portrayed in the short story. Your reflection can include things outside of personal experience or feelings, too. Perhaps you have an opinion or idea about thematic or literary device elements. Or maybe you just have some confusion, and your questions become the basis for some journal reflection about what you just read.

How is “mindful” reading important?

Ok, you’re thinking, “Wait—isn’t all reading mindful, as we use our minds to read and understand a text?” Yes and no. Mindful reading is about mindset, and often a personal and authentic mindset or approach to the “act” of reading itself. So, let us first define “mindfulness” as a practice. John Kabat-Zinn, a leader in mindfulness practices, defines mindfulness as an “awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally.” In a way, it is creating a contemplative space for yourself to engage personally, to slow down and to attend carefully to your own reading process and the very act of reading as a way for not just cognitive understanding, but for personal awareness and fulfillment.

While many of the practices we have encountered in this essay are all elements of paying attention in the present moment without judgement of ourselves or authors, mindful reading is the act of stimulating personal insight. This might even include identifying what space or “mindset” helps you engage with a text. It might mean setting up a comfortable space for reading without distraction, or it might mean understanding your own processes for engaging with a text. It might even mean a deeper, personal reflection.

In fact, many ancient wisdom traditions used mindful reading to understand sacred texts on a deeper level and to stimulate insight and present activity, which is a form of mindful reading. Reading, then, is a contemplative practice and a method of inner inquiry. Readers within ancient wisdom traditions were not reading for the type of analysis and synthesis you might be asked to do in a literature course. For these readers, it was not about identifying point-of-view or narrative structure. Instead, reading itself became a sort of meditative practice that benefited not just the reader’s mind, but the reader’s authentic nature and insights.

Whether it be in the Buddhist, Christian or other contemplative traditions, records show these ancient readers often all engaged in similar mindful or contemplative practices. For example, in some early Christian traditions, contemplative approaches to reading texts included lectio (reading and understanding a text—something we’ve discussed), meditatio (reflection and contextualizing the meaning—again a practice outlined in this essay), oratio (listening within and living the meaning), and contemplatio (being still and meeting the “divine” in the text). As the authors of Contemplative Practices in Higher Education describe, “It was a fundamentally contemplative approach: first becoming keenly aware of what was on the page and then successively attending to greater and deeper meaning within, building to the realization of global and divine connection” (Barbezat and Bush, 111).

While reading for college literature courses may not be the same as many wisdom traditions of reading for “the divine experience,” many mindful practices may still help engage active and mindful reading for more enhanced awareness of a text and ourselves as a reader. Mindful reading may be as simple as centering yourself in mind and body before reading, reading the passage reflectively several times, and considering questions—“What speaks most profoundly to me here? What does my inner teacher want me to hear?” (Barbezat and Bush, 118)—and then writing for a few minutes to log the experience of the process of reading.

Reading with the mindful intention of personal process in addition to accessing the text’s content can have important benefits for the reader. Not only are you, the reader, engaging in the literal/narrative level of a text, but you are then open to the more profound ironic or metaphoric level of meanings. And lastly, you may find yourself open to the reflective level in which you might relate or have personal responses, questions or identifiers with the text. This reflective nature of mindful reading can also enhance concepts of reader response.

So, what does this all mean for me as a reader?

While there are many purposes for reading literature—whether it is for a class assignment and/or to just better understand a piece of literature more deeply and personally—active and mindful reading can help unlock a text’s enduring qualities, as well as our own understanding of ourselves and our world around us. In fact, literature, itself, can be considered a record of the human condition. For example, it is one thing to read about WWII and the Holocaust, but there is an entirely new perspective offered when reading Anne Frank’s diary (Diary of a Young Girl) of her thoughts, emotions, and experiences of living at that time, in that setting and in that historical context; and, how we might identify with that very human condition from our own lens of experience, or not. So, whether you engage in some or all or some of these practices to unlock a text through multiple activities explored in this essay, you are one step closer to unlocking the puzzle of what it means to be a human being and a global citizen through the lens of literature.

Works Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. The Thing Around Your Neck. Fourth Estate, 2009.

Barbezat, Daniel P. and Mirabai Bush. Contemplative Practices in Higher Education. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2014.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

Frank, Anne. Diary of a Young Girl. Doubleday, 1952.

Hrabal, Bohumil. Too Loud a Solitude. Translated by Michael Henry Heim. Harcourt, 1992.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Mindfulness for Beginners: Reclaiming the Present Moment and Your Life. Sounds True, 2016

Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. 1988. Daunt Books, 2018.

Stevenson, Robert Louis and Richard Dury. The Annotated Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Ecig – Edizioni Culturali Internazionali Genova, 2005.