7 Part 1: China (East Asian Literature and Literary Criticism)

Daniel Baird

Let’s begin with China. As stated in the introduction, China’s literary history spans some 3000 years. With such a long history, only a brief introduction of the most important ideas, movements, and people will be possible here.

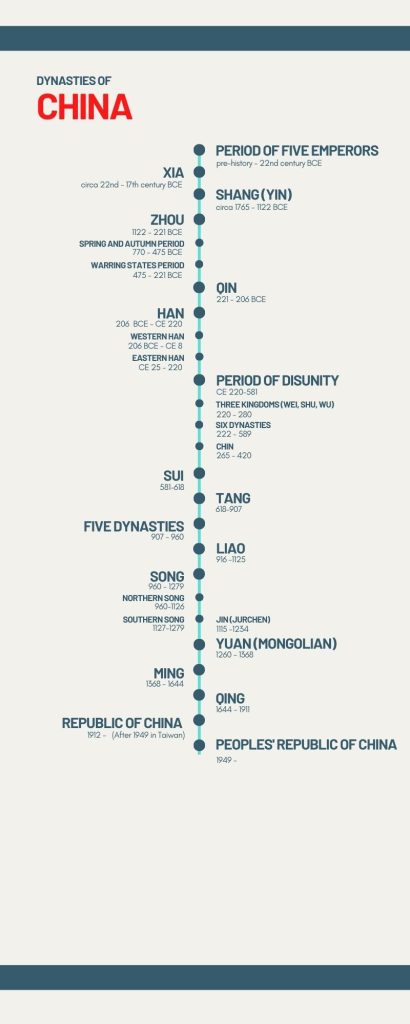

When discussing literature from China, it is common to refer to which dynasty it was produced in. Please see the following chart on the Dynasties of China:

Fig. 1. A brief timeline depicting the major dynasties of China. Chart by Daniel Baird. CC BY-NC.

In order to understand the literature of China (as well as Japan and Korea) it is also necessary to learn a little about Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, since these traditions shaped ideas and stories.

Confucianism

Confucius (551–479 BCE) stands as a giant in Chinese history and his impact on culture, literature, government, and more throughout East Asia cannot be overemphasized. A minor official who lived at the end of the Spring and Autumn Period, Confucius wrote a history of the Zhou Dynasty praising the earlier years as a Golden Age, which saw what he considered the cultural and historical height of China. Much of what we know about Confucius and his teachings comes from his disciples, who wrote down his teachings in The Analects of Confucius. Although Confucius’ ideas were not widely adopted in his lifetime, they became state doctrine in the Han Dynasty and continued through the last dynasty, the Qing Dynasty.

Confucius was concerned with a person’s behavior in society and emphasized one’s relationship to others in a sense of hierarchy. We see these relationships as the staple of literature and expressed throughout East Asian culture. Additionally, being able to do things correctly or properly was important (it is said that Confucius quit a job because the court did not observe the rites properly) and that one should cultivate virtue. One such virtue would be benevolence, and another was filial piety, or the virtue of respect for one’s parents. Filial piety is also one of the five social relationships.[1] Even rulers had to cultivate virtue, for heaven punishes wicked rulers while good rulers bring about social order. Girls were to cultivate the three obediences and four virtues: obey your father, your husband, then your son (after your husband’s death), and have virtue in action, speech, appearance, and chastity. It was through cultivating morality, then, that Confucian leaders sought to rule their people.

Because of the emphasis on how to rule society, there was an insistence on what is known as Confucian Pragmaticism: the purpose of literature is to be used for pragmatic and social purposes, rather than expressive and individual ones. In other words, although the literati were aware of emotional effects and aesthetic qualities of literature, these were to be considered subordinate to the moral and social functions of literature. Literature was meant to teach people how to act properly.

Confucianism underwent a change beginning in the Tang Dynasty and culminating in the Song Dynasty as it developed metaphysical theories in response to Buddhism and Daoism. This is called Neo-Confucianism, and it is the most important form of Confucianism to impact later literature in China and in Korea.

Zhu Xi (1130–1200), a scholar of the Song Dynasty, was the most influential for Neo-Confucianism. He wrote extensive commentaries on all the Confucian classics and added the writings of Mencius to the Chinese imperial examinations. Zhu Xi sought to reject the superstitious and mystical elements of Buddhism and Daoism by creating a rational metaphysics. This meant that the universe could be understood through human reason rather than through religion.

For more on the literary movements influenced by or in reaction to Confucianism, see Appendix 2 below.

Themes found in Confucian literature include:

- filial piety: a respect for parents

- friendship

- moral uprightness of the hero

- faithfulness of a wife, including tales of supernatural wives

Du Fu (712-770) is a great example of a poet that uses Confucian themes in his writing.

Buddhism

Mahāyāna Buddhism entered China via the Silk Route during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). In East Asian literature, the most influential sects of Mahāyāna Buddhism are the Pure Land and Zen. Pure Land worships Amida or Amitābha Buddha, who will reincarnate into heaven those who call upon his name. It was one of the earliest and most influential sects of Buddhism in China.

Zen (Chan) Buddhism was founded circa the 5th or 6th century by the Chinese monk Bodhidharma, who is also the founder of Shaolin martial arts. Influenced by Daoism, this form of Buddhism emphasized meditation and self-restraint, and de-emphasized reason and Buddhist sutras (scriptures). During the Song Dynasty koan (gong’an) collections became popular along with collections of sayings and deeds of famous monks appended with their poetry and commentary.

Several themes found in Buddhist stories include:

- desire causes suffering

- the world is an illusion

- impermanence: all thing are subject to constant change

- karma and rebirth (reincarnation): the idea that what one does in this life will affect later lives

- one needs to develop compassion for all living things

- withdrawing from society, especially the imperial court, is praiseworthy

- meditation, especially on or in nature

Wang Wei (699-759) was a friend to Du Fu and is considered an exemplary Buddhist poet.

Daoism

Daoism originated In China before or during the 6th century BCE. The most important text for Daoism is the Classic of the Way and Cultivation written by Laozi (or Master Lao, 6th century BCE). This text introduces certain concepts such as the importance of the Dao, which is usually translated as the Way, meaning the right way to act and understand things in a philosophical sense. But the very first sentence of the Classic immediately introduces the reader to a fundamental idea in Daoism: language is inadequate to understand truth, and reason is not the key to understanding things. The Classic of the Way and Cultivation is notoriously difficult to translate because of this fundamental concept.

This rejection of reason is also found in Zhuang Zhou’s (c. 369-286 BCE) book, Zhuangzi. In his book, Zhuang describes the ideal sage, which contrasts with the Confucian scholar. The Confucian ideal is cultivating virtue and social harmony whereas the Daoist sage seeks detachment and spontaneity through withdrawal from society and its conventions to live in harmony with nature. Later in literature it becomes a trope that a Confucian scholar who is slandered in court will withdraw (often to a hut in the mountains) to pursue the way of the Daoist sage.

The third important text for Daoism is the Classic of Changes. Daoism is not just a philosophy, but also a religion and is centered around divination. Divination requires a knowledge of the basic forces of nature, beginning with the complimentary forces of yin — which represents dark, cold, female, negative — and yang, representing light, hot, male, and positive. Often this duality is mistakenly seen as opposites, but this is not accurate for Daoism. Instead, as signified by the yinyang symbol, this is a complimentary duality in constant motion with yang found in yin and yin in yang. (See Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. The yinyang symbol; also called the taiji picture. Picture is public domain from Pixabay.com.

From yin and yang arise the five phases: water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. Each phase represents certain characteristics found in the universe, and they interact in complicated ways such as astrology, days of the week, seasons, and geomancy. [2] Yin and yang, and the five phases and their associated concepts are found everywhere in East Asian culture and literature.

Daoism then has a metaphysical view of literature—it explains one’s relationship with the Dao. One should live in harmony with the way often described as action with intent or “nonaction.” Often this nonaction is seen as spontaneity.

Like in Buddhism, with Daoism one is encouraged to withdraw from society and seek detachment. This leads to praise of nature and using terms such an “uncarved block” or “uncut tree” to help a person understand the way. In other words, in contrast to Confucian emphasis on the need to cultivate oneself, with Daoism one should try to return to nature as much as possible. Interestingly, Confucians are often seen as serious while Daoists more often emphasize humor.

Yet this doesn’t mean that there isn’t a Daoist version of cultivation. In Daoism alchemy, astrology, fengshui, and folk religion have all intertwined, and in literature we see Daoism associated with magic.

Themes seen relating to Daoism include:

- withdrawal from society and living in harmony with nature or taking nature as an example

- wu wei: effortless action or acting without intention; the common comparison is to be like water in the way it is both effortless and is yielding in nature

- exorcism of evil spirits, fengshui (divination), magic, associated with alchemy

- tai chi and qigong as a way to cultivate internal or soft style of martial arts

Li Bo (also called Li Bai, 701-762) is a famous poet that uses Daoist themes. Another writer associated with Daoism is Tao Yuanming (also called Tao Qian, 365-427).

Literary Themes and Ideas

Sometimes a story or poem is clearly Confucian, Buddhist, or Daoist in the themes it contains, or sometimes they are found together. One example of the intertwining of ideas comes from “Mulian Rescues his Mother,” a story that follows a man as he seeks the help of Buddha to help his mother escape hell. This early 9th century story is borrowed from the Yulanpen Sutra, yet Confucian filial piety is intertwined with Buddhist themes of karmic punishment and redemption.

Common story genres and themes in Chinese literature include:

- Cultivation: the necessity of study and practice to achieve one’s goals; although can be seen as a religious idea, it is also found in Confucianism

- Detective or mystery stories: a clever protagonist solves murders, thefts, etc., which often have a supernatural element involved

- Martial arts: whether as practiced by wandering heroes or by famous generals on the battlefield, the important (real and imagined) schools, secret moves, and secret manuals create action in many stories

- o flying swordsman: this is a fantasy version of the martial arts where supernatural powers and supernatural creatures feature predominately

- The scholar & the beauty: since many of the writers and readers were literati (government officials or those preparing to become officials), many stories feature literati or scholars as the protagonist who falls in love with a beautiful woman; the supporting cast often includes the beauty’s maid (usually both helps with lovers’ rendezvous and for comedy) and the father of the bride-to-be, usually a high-ranking official

- Strange tales: stories that feature some supernatural creature such as a fox-fairy or unusual plot such having an adventure in a dream

Some Important Authors and Works of Chinese Literature

Two genres have dominated the literary output of China: poetry and nonfiction (prose). Poetry was considered the highest form of literary expression. Confucius stated that studying of the Classic of Poetry is both useful for one’s self-cultivation and for learning their proper place in society (see The Analects of Confucius, XVII: 9). The Classic of Poetry has 305 poems containing folk songs, hymns, and eulogies that are ritual and sacrificial songs, as well as dynastic hymns that praise the founders of the Zhou Dynasty. The Tang Dynasty is considered the “golden age” of poetry in China and features some of the most famous poets: Li Bai, Du Fu, and Wang Wei, among others. Because of its long history, there are many poetic forms and famous poets.

Nonfiction writing, whether official writings such as imperial histories or personal writings, played an important role in any author’s life. Most of the authors were scholar-officials, or literati (an educated class who often were in the service of the government) and many stories feature the literati as main characters. From the Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 BCE) through the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) there were many early important texts, including the five Confucian Classics:

- Poetry: oldest compilation of poetry, consisting of folk songs, hymns, and eulogies

- Documents: contains documents and speeches of rulers and officials from early Zhou

- Rites: ancient rites, social forms, and court ceremonies

- Changes: divination system, large cultural influence beyond just Confucianism

- Spring and Autumn Annals (written by Confucius) historical record of the feudal state of Lu

During the Warring States period that followed the collapse of the Zhou Dynasty, there were many competing philosophers and statesmen who vied to serve the kings of the various states. They and their writings are referred to as the period of 100 Philosophers, where 100 simply means many. Some of these philosophers included Master Zhuang (Daoist), Mencius (a disciple of Confucianism), Writings of Master Mo, and the Writings of Han Feizi (Legalism). Legalism, so named because it promoted rule by law and a strong central government (as opposed to rule by morality and social order promoted by Confucians), was adopted by the first emperor of China in the Qin Dynasty.

The famous Art of War dates to this period as well. Considered one of the greatest treatises on how to conduct war, its author Master Sun Wu (544-496 BCE) covered such topics as planning a siege, formations, maneuvering armies, terrain, and the use of spies. The book spread to other countries and today is used in business strategy, gaming contests, etc.

The Records of the Grand Historian were written in the Han Dynasty by Sima Qian (c. 145- c. 86 BCE), who is considered the father of Chinese history. His work served as a model for writing history in later China. Japan and Korea also adopted its structure and writing style for their imperial histories. It includes not only annals of history but also biographies and treatises. He has sections on assassins and wandering knights-errant that would become the foundation for later fiction on martial artists.

Elementary learning became common for children of higher classes as early as the Han Dynasty, and treatises and anthologies were compiled for both boys and girls for learning. The most famous is the Song Dynasty’s Three Character Classic. Using Confucian morals, this text uses couplets of three-character lines to teach children to read.

The Classical Prose Movement of the Tang and Song Dynasties produced many great essay writers, and there is a collection of the Eight Great Masters of the Tang and Song. Three of these stand out even from the eight. Han Yu and Ouyang Xiu are introduced in Part II Literary Criticism. The third is Su Shi (1037- 1101), a literati who in addition to being an essayist and poet was, similarly to many literati of this time, a painter and calligrapher.

Alongside poetry, prose also continued to be a mainstay of writers through the Qing Dynasty, but the golden era is considered to be The Classical Prose Movement of the Tang and Song Dynasties. You can learn more about this in the section on literary criticism.

Poetry

The poetry and prose anthology Selections of Refined Literature (compiled by 530 CE) not only influenced Chinese literature but also greatly influenced Japanese and Korean literature. It was the basic textbook for learning to write and was part of the imperial examinations that created the educated class known as the literati.

The first common subgenre of poetry was old-style poetry that imitates poems collected by the Music Bureau of the Han Dynasty. There is no set poem length, and the line length is also uneven, although many seem to have five- or seven-character line length. The most famous of these are the anonymous Nineteen Old Poems included in the anthology Selections of Refined Literature.

Another form of poetry that was popular in the Han Dynasty is rhymed prose or rhapsody. These were recited everywhere from formal occasions to parties and were characterized by their ornate diction that was used to praise the chosen topic. Rhymed prose has neither set line length nor overall length. These continued in popularity through the Song Dynasty.

Regulated verse became popular in the Tang Dynasty. These poems are rhymed on even lines and were usually in either couplets of four or eight lines. They had either five or seven characters per line with a caesura, or pause, before the last three characters of any line. Another important feature was the tonal parallelism. Chinese is a tonal language and rhyme and tone dictionaries of this time help us reconstruct the aural features of these languages.

In the Song Dynasty, lyric poetry based on musical song tunes had uneven line lengths and were categorized based on either fast or slow tempo. The association with music and later Yuan drama continued with poetry known as arias.

Most of these forms continued through the rest of the Chinese Dynasties, but the Tang Dynasty is considered to have been the high point or golden age of poetry in China. Although there were many great poets of the Tang, and other dynasties, we will look at only four here who stand out as the most famous.

Li Bai (also Li Bo, 701-762) is the first of a trio of contemporary poets that together are the three poet sages of the Tang Dynasty. He is traditionally associated with Daoism. Unlike many poets of his generation, Li Bai did not take the imperial examinations. Rather he is famous for his knight-errantry in wandering, drinking, and engaging in sword play, even having killed several men. Li Bai excelled at old-style poetry as well as regulated verse.

Li Bai was friends with Du Fu (712-770), whom he met in 744. Du Fu is often thought of as representing Confucianism in his poetry. Du Fu failed the imperial exams twice, though he still did receive minor official posts. However, his attempt at an official career was derailed by the An Lushan Rebellion (755-763) that threw the country into turmoil. Du Fu’s poetry is much more concerned with the social problems of the time. Du Fu also wrote both old-style poetry and regulated verse.

Wang Wei (699-759) is the last of the trio and was friends with both Li Bai and Du Fu. Unlike the other two, he had a successful court career, but he eventually became devoted to Zen Buddhism. Wang Wei wrote in four-line regulated verse and is especially known for his poetry on “mountains and streams.” He also founded the Southern School of Chinese landscape art.

Bai Juyi (772-846) served as a government official and used his poetry to write about social problems of his day. He wrote both old-style poetry and regulated verse.

Nonfiction (and genre)

Since the Han Dynasty, writing was generally divided into four categories that do not match our Western categories of genre. The famous imperial anthology of the Qing Dynasty, The Four Storehouses, gives these categories:

- Confucian classics and their commentaries

- Historiography: such as official histories, regional histories, biographies, regulations on statecraft, etc.

- Writings of the Masters: ranging from philosophy, science, military books, agriculture, medicine, astronomy, mathematics, divination, art, Daoist and Buddhist writings, and fiction

- Literature: mainly focused on poetry and prose, but also included literary criticism

It is important to note that fiction was a subgenre of 3) Writing of the Masters, not of 4) Literature. Although it was popular, fiction was never considered as “serious” or important literature and literati usually hid their authorship by using pseudonyms or even writing anonymously. Here drama doesn’t even exist as a subcategory.

One famous anthology, the Selections of Refined Literature, was compiled by 530. It has 38 categories of poetry and prose and influenced not only Chinese literature but also Japanese and Korean literature. It was the basic reader for learning to write and formed part of the imperial examinations through the Tang Dynasty. From this we can see that Chinese literati viewed genres differently than the West.

Today, however, Chinese literature is generally studied in terms of the major literary genres as understood by the West: nonfiction, poetry, fiction, and drama.

Fiction

One of the earliest influences on fiction is the Classic of Mountain and Seas, a compilation of mythic geography and beasts, and although it predates the Han Dynasty, the current version is from then. It is the source of many ancient myths such as Nu Wa, who created humans and mythological creatures such as the Chinese version of the unicorn.

Although storytelling in oral form had been around much earlier, the Han Dynasty saw the recording of simple stories about spirits, ghosts, immortals, and deities, known as tales of the strange. One of the most famous early collections of these are by the historian Gan Bao (d. 336). The collection In Search of the Supernatural contains stories of Chinese gods, ghosts, monsters, and similar beings.

One notable author early on is Tao Qian (also Tao Yuanming, 365-427) because, although known primarily for his poetry, he wrote a small piece called A Record of Peach Blossom Spring, in which a fisherman stumbles upon a utopian society. The title of this work became the Chinese word for “utopia.” Tao Qian is also noted for the Daoist themes of his poetry and for having established the fields and gardens landscape poetry subgenre. His writings are collected in the Selections of Refined Literature.

Buddhist short stories enter during the Six Dynasties period but became less popular by the Song Dynasty. These stories taught Buddhist theology through the actions of their characters. One of the most famous is “Mulian Rescues his Mother.” This early 9th century story borrowed from the Yulanpen Sutra, yet Confucian filial piety is intertwined with popular themes of karmic punishment and redemption showing how Confucianism and Buddhism were intertwined in fiction.

A famous example of the tales of the strange stories genre is the later collection by Pu Songling (1640-1715), Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. There are some five hundred stories covering a wide range of supernatural tales that also contain social criticism.

Romantic stories abound in fiction (and drama), with the most famous subgenre being the scholar and the beauty where a young scholar seeks the hand of a beautiful young women. In The Peony Pavilion by Tang Xianzu (d. 1616), the daughter meets the scholar through a dream, falls in love, and dies of love sickness. However, the King of the Underworld is confused because according to his records the two are supposed to marry. Eventually all obstacles are overcome, including the daughter coming back to life and the scholar passing the highest level of the imperial examinations.

By the Ming and Qing Dynasties, novels were being written and the most famous novels were produced in this dynasty, such as the ever-popular Journey to the West. This work is based on the historical figure of Xuanzang (602 – 664), a monk who traveled from China to India to study and translate scriptures. His story has been recounted in plays, short stories, and the novel written by Wu Cheng’en (c. 1500-c. 1582). The favorite character in the novel is a monkey guardian who, along with other guardians, protects Xuanzang from the many demons they encounter on this journey. One of the main adaptations and retellings that this novel has inspired is the Dragon Ball manga/anime franchise by Akira Toriyama. Here Son Goku (Sun Wukong) is the name of the monkey and Xuanzang’s search for Buddhist scriptures are turned into Bulma’s search for the dragon balls.

The most famous love story of this time is Dream of the Red Chamber (Story of the Stone) by Cao Xueqin (c. 1715-1764). Themes from all three major traditions – Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism – are used to tell the story of a stone and the flowers that grew around the stone who are all reincarnated as a young nobleman and his wives/maids to experience human life.

Martial arts stories full of heroes and knights-errant are very popular. Outlaws of the Marsh (The Water Margin) by Shi Nai’an (1296-1372) is a Robin Hood-like story where 108 outlaws together to rebel against the corrupt Song government. The book chapters are in cycles, with each cycle introducing a new main character until all the main characters are gathered.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong (c. 1300s) is based on the historical period of the Three Kingdoms and gives a fictional account of the lives of the historical figures that played important roles in the war that determined the fate of the three kingdoms. It includes the famous oath of brotherhood scene, which influences much later fiction and cinema.

Two real-life judges often served as the basis for detective or crime stories and novels. The first is the Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, a 1700s novel by an anonymous author loosely based on the Tang Dynasty county magistrate Di Renjie (630-700). The second is The Three Heroes and Five Gallants, an 1879 Chinese novel that follows the Judge Bao and his group of martial artists/knights-errant who helped him solve cases. Judge Bao (999-1062) was a real-life judge from the Song Dynasty who demonstrated extreme honesty and uprightness.

Drama/Opera

Shang Dynasty has some mentions of dancing and singing associated with shamanism while the Zhou Dynasty has records of court entertainers, and other forms of comic performances and masked dance drama. But it was not until the Tang Dynasty that the first known opera troupe, the Pear Garden, was founded. This troupe mostly performed for the emperor’s entertainment.

During the Song Dynasty, the 100 entertainments associated with the entertainment districts were popular. These entertainments could include storytellers, arias interspersed with narrative, acrobatics, and dances. From these early entertainments, Chinese drama or opera developed.

During the Yuan Dynasty, four- and five-act miscellaneous plays became popular. Usually there was just one major singing role per act that had several supporting characters. Yuan drama often continued to feature the acrobatics and comic skits of the earlier 100 entertainments in between the acts. The most famous play of this type is Wang Shifu’s (1250-1337?) Romance of the Western Chamber, which tells a story of the love between a young scholar and the daughter of an important minister of the Tang court. The obstacles thrown in the lovers’ way include the fear of bandits, a rival love interest for the daughter, and the requirement that the young scholar pass the imperial examination.

During the Ming Dynasty, drama became more sophisticated with varied length in acts and an increase in number of characters that could sing. The emphasis thus became more on song and the narrative story. One subtype of Ming drama was the Kunqu opera, so named because it originated from the Kunshan region of China.

Many masterpieces of Chinese theater/opera stem from this time, with The Peony Pavilion by Tang Xianzu (d. 1616) described above as the most famous.

In the mid-Qing Dynasty another form of opera, Beijing Opera, coalesced from older forms and became extremely popular. Beijing Opera emphasizes spectacle and is known for its striking face paint—some representing specific characters while others represent character traits in general—and acrobatics. There are many famous operas including Journey to the West featuring the monkey king, Sun Wukong.

Literary Criticism

Earlier Literary Movements

Early writings such as The Analects of Confucius only contain brief references to thoughts and ideas on literature, usually on poetry. Later literati would glean from these references and establish the purpose of literature. For example, from Confucius one can infer that since cultivation is required to become the ideal Confucian, literature therefore must also be carefully crafted.

The oldest surviving treatise of literary critique is Cao Pi’s (187-226) “A Discourse on Literature.” This work introduced the concept of genres in writing, but the heart of Cao’s work promotes four major ideas:

- one should value another’s writing

- each type of literature has different types of requirements and literati should master them all

- a discussion on vitality[3] and how this relates to the quality of a person’s writing

- literature serves the purpose to regulate and maintain social order (Confucian pragmaticism)

It is these last two ideas that would have lasting impact on literary criticism. The fourth simply is expounding on the widely accepted Confucian ideas of literature. But the idea of vitality becomes an important concept in debates that arose at the end of the Han Dynasty. Basically, literati debated the importance of form versus content. Vitality was important to creating content, but could vitality be cultivated or was it something that a person was born with? This led to debates on what was considered outward embellishment versus natural writing.

One of the more important schools that would emerge to take up the debate on literature was the School of Mystery of the Three Kingdoms Period. Although Confucian literati, the members of this school of thought worked on reconciling Confucianism with Daoism.

The later “Seven Masters of the Bamboo Grove” continued combining Confucianism and Daoism. One important writer of this group was Ruan Ji (210-263), who avoided court service and instead sought a Confucian version of withdrawal similar to the Daoist sage. The Seven Masters rejected Confucian cultivation through ritual and education, feeling such would overshadow the influence of nature. This was in direct opposition to Confucian teachings on the need to cultivate oneself. This defining of Confucianism through Daoist metaphysics is found in their poetry.

Another important figure of this time was Lu Ji (261-303), who came from a military family, served in the government during this chaotic time as a literary secretary and general, and was executed for losing a battle. He wrote the Exposition on Literature, a collection of short poems that functions to describe what good writing is. It contains topics such as studying works of past masters, how to start writing, choosing words, a brief catalog of genres, revision, originality, form, and dealing with writer’s block.

Zhong Rong (c. 468-518) wrote the first major work devoted exclusively to poetry critique and contributed greatly to the development of literary criticism. He was responding, in part, to Zhi Yu’s (d. 311) Records of and Discourses on the Ramifications of Literature that looked to past writing, especially the Classic of Poetry, as the only way to write poetry, frowning upon newer forms. In contrast, Zhong evaluates the great poets from the Han Dynasty to his own times and pointed out that modern forms of poetry were acceptable and were more readily able to express personal feeling. He stressed that good poetry is an expression of life while avoiding the overemphasis of form. Zhong’s work An Evaluation of Poetry gave rise to the genre of poetry criticism that became very popular in the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

The most comprehensive and famous of all Chinese works on literary criticism is The Literary Mind and Carving of Dragons, completed in 502 by Liu Xue (c. 465- c. 520). He grew up studying in a Buddhist temple and only held minor government posts before retiring to the monastery again where he edited sutras and wrote his book of literary criticism. Its title, The Literary Mind and Carving of Dragons, refers to “the expression of feeling and thought in embellished language.”[4] This expresses one of the central themes of the work: emotion leads to language and ideas lead to writing. Liu argues that one should have empathy—the ability to feel and understand what writers of other places and of the past feel and think. It is this empathy that demonstrates cultivation or refinement. Literature therefore is intrinsic to humanity and a central part of the Dao—the primal source of existential and literary phenomena; the great philosopher-writers of the past are the wisest interpreters of the Dao, and therefore their writings are the most desirable, with Confucius being the most important of them all. Finally, Liu feels that literature reflects the social conditions of the time, which results in either artistic growth or decline.

Like Cao Pi, Liu discussed vitality and its importance as a concept. He refers to ancient examples, talks about how vitality is important to writing, and the need to remain tranquil.

Liu had much to say on style and rhetoric. Style is based on the individual’s (Confucian) cultivation including education and talent. He discusses the style of twelve individual authors including the “Seven Masters of the Bamboo Grove” and creates a list of eight important styles:

- elegant

- recondite

- concise

- plain

- ornate

- sublime

- eccentric

- frivolous

After his chapters on style, he moves on to rhetoric where he discusses things such as choice of words, sentence and paragraph arrangement, organization of compositions, parallelism, comparison, metaphor, hyperbole, allusion, etc.

Parallelism should be emphasized here. This feature arose in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) and pervaded both nonfiction and poetry. Liu discusses how everything in nature has pairs and therefore, “In the proper arrangement of thoughts, it naturally falls into pairs.”[5] Like other chapters, he begins by referring to important examples of the past such as the Classic of Poetry and Classic of Changes to prove his argument that parallelism is natural in writing. He then organizes them into four types of parallelism and provides examples for each and then ends with a summary on the topic.

His ideas on style and rhetoric can be summed up as promoting harmony/unity, promoting propriety, and being opposed to excessiveness.

Later Important Movements in Chinese Literary Criticism

The Tang Dynasty (618-907) saw a new development in poetry criticism with the poet Wang Changling (698–756). He wrote his work A Discussion of Literature and Meaning and borrowed terms from Buddhism to create a new critical vocabulary. Wang prioritized the connection between poet and audience through the mood of the poem, especially using nature imagery.

Another Tang writer was Han Yu (768-824), an important figure in the Classical Prose Movement. Han advocated for an aesthetic return to the old prose style of pre-Han Dynasty writers rather than the formal, richly ornamented style that relied heavily on parallelism that was predominant in his time. The style he advocated for was not simply an imitation of the old classics, but rather the ancient ideals of clarity and concision. Han Yu was very much for Confucian authority and orthodoxy and against both Buddhism and Daoism and was a forerunner of New-Confucianism.

Confucianism underwent a change beginning in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and culminating in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) as it developed metaphysical theories in response to Buddhism and Daoism. This is called Neo-Confucianism and is the most important form of Confucianism to impact later literature in China and in Korea. Zhu Xi (1130–1200) was the most influential scholar-official for Neo-Confucianism. He wrote extensive commentaries on all the Confucian classics and added the writings of Mencius to the Chinese imperial examinations. Zhu Xi sought to reject superstitious and mystical elements of Buddhism and Daoism by creating a rational metaphysics. This meant that the universe could be understood through human reason rather than through religion.

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Ouyang Xiu (1007 – 1072) continued to promote the Classical Prose Movement. Because he was a member of the prestigious Hanlin Academy and led a team of historians to write the official New Tang History, Ouyang’s ideas on prose were influential. Ouyang promoted reason and frowned upon superstition in the New Tang History, marking a departure from other histories. He also wrote a series of “talks on poetry” that became the forerunner of many later Song Dynasty poetry theories.

“Talks on poetry” were short statements about poems and poets, writer’s ideas on poetry including both form and content, and responses to other writer’s ideas, but they are characterized as not having any sustained argument. By the latter half of the Song Dynasty onward, this became the standard way of presenting one’s views on poets and poetry.

The first study focused solely on rhetoric was the Principles of Writing by Chen Kui (1128-1203). Its ten sections draw mainly from the Confucian classics to study literary devices such as parallelism and metaphor. He also praises spontaneity and simplicity as important in composition.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) is characterized by a wide range of literary movements. The Classical Prose Movement declined, and the Archaic School was established. The Archaic School held up prose of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) and Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) and the poetry of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) as the only acceptable models of writing and the imitation of these models as the only acceptable way to achieve literary excellence. They also promoted the Confucian idea that goes all the way back to the Classic of Documents that literature was to promote social order.

However, during this time a debate arose over the importance of emotion that soon moved to center stage. The Archaic School acknowledged that emotion played a part in the value of literature, but it was really the Gong’an School that promoted that good writing was the result of genuine emotions and personal experience. The Gong’an School was founded by three brothers, of whom Yuan Hongdao (1568–1610) is the most famous.

The Gong’an School was openly critical of the dominant state ideology, Neo-Confucianism, and saw value in the evolution of literature through the ages. This led to the promotion of vernacular over ancient prose. Because of this the Gong’an School saw value in fiction and drama as well as prose and poetry. Spontaneous feeling rather than deliberate contemplation was stressed; hence, the best writing was produced by those who were well educated, had a good personality, and could express genuine feelings.

The Tongcheng School is the most important for the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Founded by Fang Bao (1668-1749), who was an advocate of Han Yu’s Classical Prose Movement, the school held sway for most of the Qing Dynasty. Fang developed a literary theory that sought to harmonize substance and form. Substance was understood as being in harmony with Neo-Confucian teachings while form was based on the writings modeled on great exemplars of the past. Fang compiled the Concise Anthology of Ancient-style Prose so that students would have writings to model.

Conclusion

It is important to understand how the tension between Confucian pragmaticism and personal expression informs the many debates over how to understand and create literature. On the one hand there is the need to see literature as a way to control society and show the proper way to live. On the other hand, many literati sought to free literature from such a constraining definition and emphasize instead the way literature could express individual feeling and communicate that feeling to another.

Additionally, there are the moral teachings of Buddhism and the combined emphasis in both Buddhism and Daoism to look to nature and away from society to better understand life. Sometimes in tension, sometimes coming together to create something new, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism created a rich and long tradition of literature in China.

[1] The five relationships that determine behavior in society: ruler and subject, father and son, elder and younger brother, husband and wife, and between friends (older takes precedence).

[2] For example, the days of the week were named after the five phases that are associated each with the five planets visible to the eye (Mercury-water, Venus-metal, Mars-fire, Jupiter-wood, Saturn-earth) with the sun and moon bringing the total to seven days a week. Japan still uses this system today.

[3] Defining the metaphysical concept of vitality or qi (气, often spelled chi) lies well beyond the scope of this text. Simply think of vitality as a force in nature that is necessary to life and according to Cao Pi it can influence the quality of one’s writing.

[4] Liu, p. 61.

[5] Liu, Chapter 35, p. 489.

Further Reading and Resources

China

Chou, Chih-P’ing. Yüan Hong-tao and the Kung-an School. Cambridge UP, 1988.

Han Feizi: Basic Writings. Burton Watson, trans. Columbia UP, 2003.

Liu, Xie. Dragon-Carving and the Literary Mind《文心雕龙》2 vols. Bilingual edition with modern Chinese translation by Zhou Zhenfu and English translation by Yang Guobin. Foreign Language and Teaching, 2003.

Liu, James J. Y. Chinese Theories of Literature. U of Chicago Press, 1975.

Lu, Chi. The Art of Writing. Sam Hamill, translator. Milkweed Editions, 2000.

The Art of Writing: Teachings of the Chinese Masters. Tony Barnstone and Chou Ping, translators. Shambala, 1996.

The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature. 2 vols. William H. Nienhauser, Jr. ed. Indiana UP, 1986.

Mo ZI: The Book of Master Mo. Ian Johnston, trans. Penguin, 2010.

Confucianism

Confucius: The Analects. D.C. Lau, trans. Penguin Books, 1998.

Gardner, Daniel K. Chu Hsi Learning to Be a Sage: Selections from the Conversations of Master Chu. UC Press, 1990.

Mencius. D.C. Lau, trans. Penguin Books, 2003.

Buddhism

Conze, Edward. Buddhist Scriptures. Penguin Books, 1959.

Mitchell, Donald W. Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience. Oxford UP, 2002.

Suzuki, Daisetz T. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton UP, 1993.

Daoism

Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching [Classic of the Way and Cultivation]. D.C. Lau, trans. Penguin Books, 1964.

Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings. Burton Watson, trans. Columbia UP, 1996.