1 “What Kind of Story is This?”: Genre and Literature in the Contemporary World

Jeshua Enriquez

Introduction: What is Genre?

At its simplest, a genre is a category of literature: a type of story, novel, movie, etc. When you open up a streaming app to watch a TV episode or a movie, for example, you’ll probably be faced with different rows of options based on the kind of entertainment the app thinks you enjoy. You might see labels for those categories, like “Action-Packed Thrillers” or “Romantic Comedies” or “Quirky Indies.” When you visit a bookstore, the books are grouped in shelves and locations according to certain labels: “Mystery,” “Science Fiction/Fantasy,” “Historical Fiction,” and so on. All of these are examples of genres – a way to classify stories according to things like what happens in the plot, what kind of characters they have, what setting they take place in, and even what kind of language is used to tell the story.

Categories like these are useful for talking about literature because they help us use the same language to share ideas. When I say something about “Westerns” or “comedies,” other people will quickly know the kind of stories I’m referring to, without needing a lot of explanation. More importantly, examining a story’s genre – what makes this kind of story work and what it has in common or different from other stories – leads to interesting insights. It helps us reach new ideas about the individual story, about storytelling in general, about the culture that produced the story, and about a variety of other topics.

Stories are usually classified into genres depending on their characteristics. For example, if you choose to watch a movie in the mystery genre, there are certain characteristics you expect to see. You probably expect that someone will get murdered, that a detective will investigate the crime, and that there will be clues that slowly reveal the culprit. Besides things described in the story, like people, settings, and events (called the “content” of the story), you might also have expectations about how a story is written (called the “form” of the story). You might expect a thriller to use less flowery language than literary fiction or poetry – and a romance novel has its own kind of language as well. Whether it’s a characteristic of form or content, a characteristic that is very common or typical of a genre is called a genre trope. Brilliant detectives are a trope of the mystery genre because they are so common in that type of story.

What are “the genres” that stories can belong to? Is there a list that we can check in order to classify our stories in the correct way? To help you get an overview of genres, a quick internet search can provide you with a lot of examples.[1] But the real answer is that there is no one “authority” or “master list” when it comes to genres. The decision of how a story is labeled depends on a lot of different people and factors, including the author’s intent, the publisher’s marketing, reviewers’ opinions, and very importantly: on you, the reader, and on all of the other readers’ interpretations. There is also nothing wrong with disagreeing about a story’s genre – many writers and readers have differing opinions, and there is not one right answer about a story’s genre (though some answers will be easier to justify than others, and often readers come to a consensus about the genres a story most belongs in).

In fact, genres often get combined, and new genres get created all the time, as authors create new stories that mix and match ingredients from different genres and try new things that haven’t been done before. In contemporary literature, transnational authors (ones who have lived in multiple countries) and multicultural authors (ones with backgrounds from multiple cultures) often draw from multiple traditions to create new kinds of stories. In these ways, thinking about genre can open up new possibilities and inspire new inventions, instead of restricting authors to certain categories or forcing them to follow certain formulas. For example, Mohsin Hamid’s novel Exit West (2016) blends the war story genre with the fantasy genre. Movies like Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) combine comedy, horror, and social commentary – an increasingly popular combination also seen, for example, in Jordan Peele’s movies Get Out (2017) and Nope (2022).

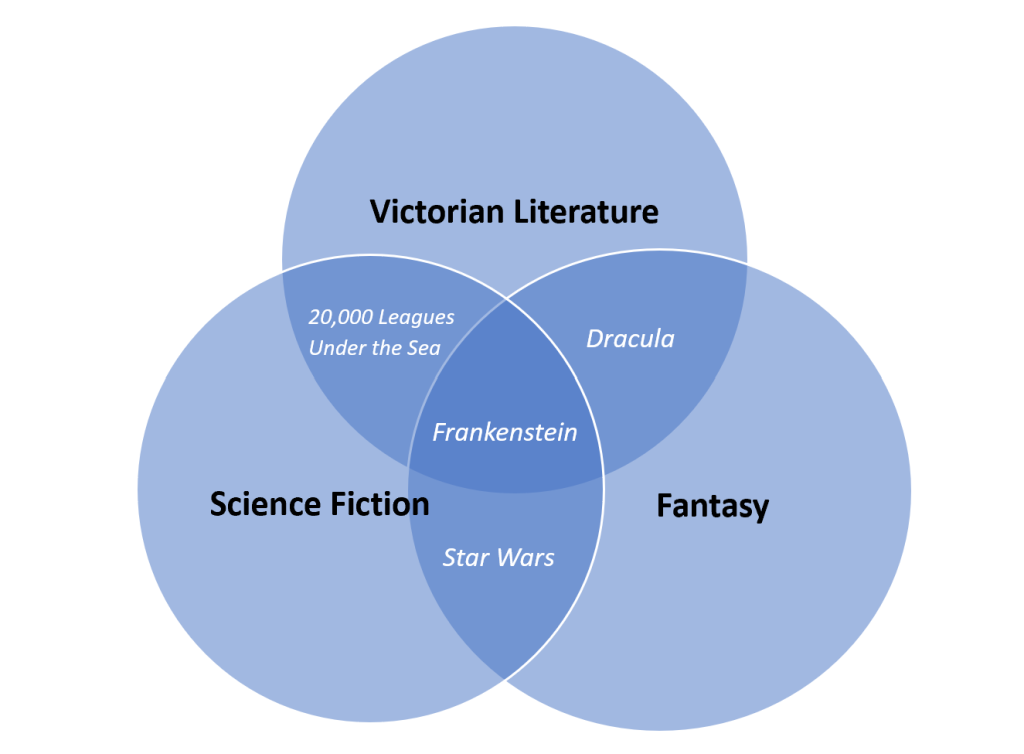

Something else to always remember is that genres are categories, which can be all shapes and sizes: they can even contain other genres, or intersect with other genres like a Venn diagram. See Figure 1 for an example.

Figure 1: A debatable Venn diagram showing how stories can belong in multiple genres at the same time, by Jeshua Enriquez, CC BY-NC.

For example, the “Fantasy” genre can hold sub-genres of fantasy inside of itself, such as “High Fantasy” and “Sword and Sorcery” and many more. The genre “Science Fiction” can hold inside itself genres like “Cyberpunk” and “New Wave.” And some stories that fit inside the science fiction genre can at the same time also fit in other genres, like romance or literary fiction. Genres are malleable and dynamic – they shift and change – and they exist for our use, so that we can use them as lenses to look through and better understand what we read.

Combining and rethinking genres, or adding new elements to familiar forms, is one way that authors make their stories original, interesting, and innovative. Along with writers’ desires to innovate, genres evolve over time as culture and society changes over time: customs change, social expectations change, technology changes, and trends change, so it makes sense that story types and categories also change over time. At one point in time, it was the norm for science fiction stories to focus on scientific descriptions and explanations; for example, such as in the work of Robert Heinlein or Frederik Pohl. During other eras, it has been common for science fiction to focus on exciting action, like in the stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs, or on social commentary, like in the work of Ray Bradbury or Octavia Butler.

One way to think about genres is that they are porous containers, like bubbles, rather than hard and closed-off boxes. Stories might move back and forth between genres as they proceed from beginning to end. The genre we believe they belong in might change over time. Categories might merge and change shape as new writers create works that mix ideas from different genres. New categories form and rise to popularity all the time. Examining how genres work and change over time can be just as important as examining individual stories.

Structuralism and Genre Studies

Scholars in different fields approach genre studies in different ways. Linguists and rhetoricians (scholars who study language and communication), for example, have explored the idea of genre as it relates to the purpose of language and how language itself works. In this reading, though, we will focus on examining genre through the lens of literature and literary studies in particular. This means we’ll be looking at genre from the perspective of stories and how storytelling works: the way literature is constructed from certain ingredients and patterns, and how we recognize or define different kinds of literature.

Some of the biggest influences on the study of genre have been scholars of literature called structuralists. Rather than referring to a group of writers who necessarily knew each other or even agreed on a majority of ideas, the term “structuralist” is used broadly for scholars who shared a particular interest in the way they studied stories. Structuralism is a massive field with a wide variety of thinkers and views, but they share the idea that an important way to make sense of literature is by examining literature as a system of relationships – relationships between words, between conventions (rules or expectations), and between genres (Guerin et al.).

This idea is based on linguistics, or the study of language, which itself is a system of relationships. For example, we know that sentences need to have a noun (a person, place, or thing), and a verb (an action). Sentences show relationships between subjects, objects, and actions in order to make meaning through words. And every sentence and word is part of the larger system of the language as a whole. Any one word or sentence by itself wouldn’t mean anything if it wasn’t part of the larger system, or structure, of the language itself.

Structuralist scholars like Robert Scholes argue that stories themselves only work as part of a larger system, through conventions (Guerin et al.), or what David Fishelov calls “generic rules” (Fishelov) – where “generic” in this context means “related to genres.” For example, movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe are easy for us to understand because they’re part of the overall structure of superhero movies. TV shows like Ahsoka or The Mandalorian make sense to us because they’re part of the system of Star Wars fiction, and also the system of science fiction as a whole. Genres work as systems, or structures, based on a web of connections: connections both between stories and also between other genres.

And because every story – and every writer – contributes to the overall system, they all have freedom over how they use genres, as well as control over what genres become (Alpers). Thinking about these systems and relationships, therefore, is an interesting way to learn not just about stories, but also about the real-world people and societies that create them.

Genre and Culture

Like we talked about in the beginning of this article, genres are lenses for us to look through in order to think deeply about stories, interpret them, and compare them. Thinking about genres helps us to create knowledge and make meaningful connections about the stories we read and how they work. Genres are tools that we use as readers and scholars – they work for us, and not the other way around. Instead of trying to fit or classify stories according to strict formulas or rules, thoughtful scholars think about what genres and genre tropes tell us.

Thinking about the genre of a story can help us know what to expect from a type of story – what kind of tropes, or common characteristics, we might expect to see. The genre of noir detective stories often features a tough, cynical protagonist who presents a tough personality but is trying to do the right thing. The science fiction genre often features advanced technology – inventions that don’t exist yet. Knowing this is usually the case can help us place stories in the larger web of genre relationships.

Genre tropes can also help us see messages and perspectives under the surface of a story. Why, for example, would the creators of the TV show The Mandalorian combine elements of space opera science fiction (an adventure through space with interesting alien civilizations and conflicts) with elements of cowboy westerns (tough outlaw characters taking the law into their own hands – or living outside the law with their own code of justice)? Examining the ways that this show uses the codes and symbols of both genre systems (space opera and westerns) can, for example, reveal underlying attitudes about government, personal responsibility, or kinship and loyalty.

Examining trends in popular genres can also give us some insight about what fears, hopes, and ideas are popular in a particular culture and/or a certain moment in time. In just the past few decades, we’ve seen surges and declines in certain kinds of stories, such as asteroids threatening the Earth, vampires, zombies, and young people rejecting their group classifications in dystopian futures. Many scholars and readers believe that the sudden popularity of these trends goes beyond coincidence – that they tell us about a worry, or alternatively maybe a desire, in society. Some critics argue, for example, that vampires reflect a fascination with “sex and violation,” for example, while zombies might represent “what we fear we might become if we let ourselves go—soulless vessels of pure appetite, both ravaged and ravaging” (Denby). Or zombies might show “our apprehension of what hostility lies behind all those blank faces in the office, at the mall, across the dinner table” in our mundane daily lives (Denby) – an interpretation easy to see in movies like George Romero’s movie Dawn of the Dead, which takes place inside a shopping mall. Some scholars even specialize in the meaning of monsters – “monster theory” – and what they tell us about our society.

Knowing about the trends and histories of genres can help us to place stories in a historical context. They can lead us to think about the social, political, economic, and other historical factors that led to a story’s creation. For example, science fiction gained a lot of its modern characteristics and rose in popularity near the end of the 19th century and throughout the early 20th century: a time when industrialization was reorganizing the way people lived, and the advancement of technology was rapidly accelerating. Gothic horror stories are known for mysterious, transcendent supernatural powers and events – and this genre arose at a time when science and rationalism were replacing a lot of mystery and supernatural beliefs in society. Examining the historical context of genres often leads to useful insights.

All stories have a genre, but some types of stories are also often labelled “genre fiction.” Westerns, mysteries, science fiction, and fantasy are examples of categories that are often referred to as “genre fiction.” Genre scholar John Rieder argues that there is something distinctive about these stories and how they developed – in particular, that it is important how these stories were marketed and presented: the way they arose and grew in the real world, including how they were treated commercially by publishers and customers (1-2). For example, there was a time when authors of novels and stories in genres like mystery and science fiction were paid according to how many words they wrote, and these stories were sold cheaply, leading to nicknames like “pulp fiction” (referring to the cheap paper used to print them) or “penny dreadfuls” (referring to the price of each book and their perceived low quality). This commercial history had a huge impact on how writers approached creating these stories, and how the genre was viewed by the public.

Traditionally, at least in the early days of their popularity, these genre fiction types of stories were considered less serious and less artful than literary fiction, or “artistic literature.” Therefore, they tended to be dismissed by scholars and looked down upon in academics, and in high-culture discussions. Today, that perspective has changed somewhat and at least some scholars look to these genres for important insights about culture and about literature. Examining the real-world context of how genres are received: how readers and critics see them and form opinions about them, can also be a valuable way to examine stories and genres.

Conclusion

Every time we read – or write – a story, we participate in the constant process of creating genres. As readers and writers, we provide our own contribution to the overall system of genres, like drawing lines or making brushstrokes on a communal mural. Thinking about that mural, the overall structure, and how each individual detail and figure tells us about culture, about society, about authors, and about storytelling, helps us to understand the big picture of literature and make important connections about the way humans tell stories – and why.

Works Cited

Alpers, Paul. “Lycidas and Modern Criticism.” English Literary History, vol 49, no. 2, 1982, pp. 468-496. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.2307/2872992

Denby, David. “Life and Undeath.” The New Yorker, 24 June 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/01/life-and-undeath.

Everything Everywhere All at Once. Directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, IAC Films, 2022.

Fishelov, David. Metaphors of Genre: The Role of Analogies in Genre Theory. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

Get Out. Directed by Jordan Peele, Blumhouse Productions, 2017.

Guerin, Wilfred L., Earle Labor, Lee Morgan, Jeanne Campbell Reesman, and John Willingham. “Chapter 5: Chapter Overview.” A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature. 6th ed. Oxford University Press, 2006. https://global.oup.com/us/companion.websites/9780195394726/student/chapter5/overview/.

Hamid, Mohsin. Exit West. Riverhead Books, 2017.

Maasik, Sonya and Solomon, Jack, eds. Signs of Life in the USA: Readings on Pop Culture for Writers. 10th ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2020.

Nope. Directed by Jordan Peele, Monkeypaw Productions, 2022.

Rieder, John. Science Fiction and the Mass Cultural Genre System. Wesleyan University Press, 2017.

[1] Wikipedia provides one such list here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_genres